Inspiration for Your Next Trip

Rosliston Forestry Centre Environmental Education Project

The National Forest is an incredible regeneration project that has reclaimed 200 square miles of land in the midlands to restore it to its former greenery. Since the 1990s, 8.9 million trees have been planted in the area. The project has been an enormous community feat, with collaboration between landowners, local charities, partners and authorities. […]

Canal & River Trust – Explorers: Caen Hill Locks and Devizes Wharf

The Kennet & Avon Canal opened in the early 19th century to link Bristol and London. At this site in Wiltshire, pupils can visit Kennet & Avon Canal Museum, located in an old bonded warehouse, to learn the story of this important waterway. Volunteers are also available to lead free learning activities at Devizes Wharf […]

Canal & River Trust – Explorers: Cambrian Wharf, Birmingham

On a visit to the Cambrian Wharf in Birmingham your students will find plenty to explore. They can take a guided trail that shows them how the locks work and discusses the different buildings that line the canals. From there, pupils can try their hand at building their own canals. They’ll learn how the canals […]

Kingswood – Dearne Valley

Dearne Valley was formerly the Earth Centre, one of the Millennium Commission projects. Situated in beautiful southern Yorkshire, just a 40-minute drive from Sheffield, this site opened its doors as a Kingswood Centre in 2012, following a multi-million pound investment programme. It is the most environmentally sustainable of Kingswood’s centres and has one of Europe’s […]

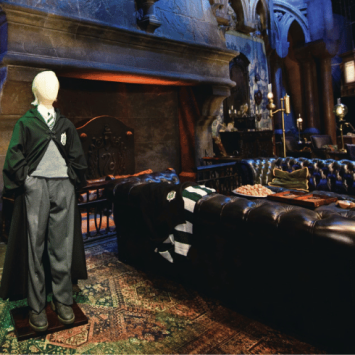

Coventry Cathedral

Finding UK school trips that cater specifically towards enhancing your student’s religious education can be challenging. Luckily, Coventry Cathedral offers a complete programme that embodies religious education, local history and fulfils educational requirements for art trips. The cathedral offers guided tours, a whole day experience, teacher-led tours, non-guided visits, and virtual visits within the various […]

Peak Activity Services – Chasewater Outdoor Education Centre

Located in Burntwood, Staffordshire, this activity centre opened in 2021. The centre offers a wide selection of activities on land and water and has options of residential or non-residential visits. Chasewater Activity Centre proudly holds the Learning Outside the Classroom award, highlighting the educational quality of the activities offered. The team put together a package […]

Explore by Subject

Explore by Region

A-Z guide on completing a risk

assessment

Download a school trip proposal

template

Explore by Type

Recently Added School Trips

School Trip Articles

Why join Teachwire?

Get what you need to become a better teacher with unlimited access to exclusive free classroom resources and expert CPD downloads.

Create free account

Thanks, you're almost there

To help us show you teaching resources, downloads and more you’ll love, complete your profile below.

Thanks, you're almost there

To help us show you teaching resources, downloads and more you’ll love, complete your profile below.

Welcome to Teachwire!

ContinueSet up your account

Thanks, you're almost there

To help us show you teaching resources, downloads and more you’ll love, complete your profile below.

Welcome to Teachwire!

ContinueSet up your account

Reset Password

Remembered your password? Login here