The Myth That Some People Aren’t Good With Numbers Is Holding Children Back

'I just can’t do maths' is a lie. Everyone can learn, and wrong answers put you on the right path

- by Wendy Jones

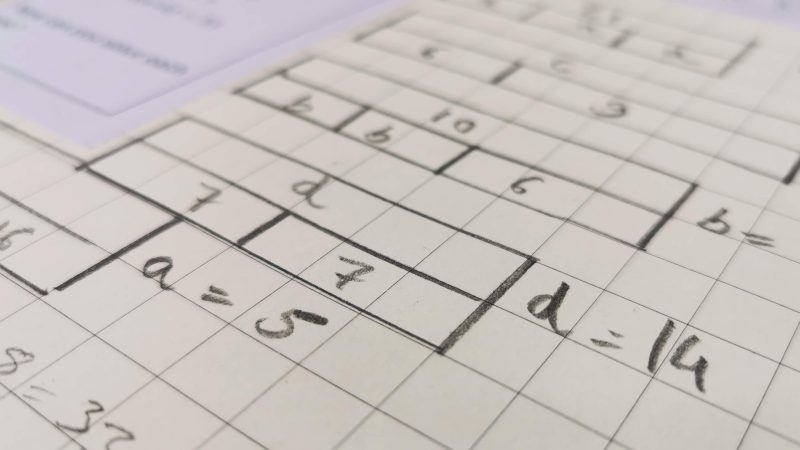

There’s a real buzz as the Larkswood Year 6s work in pairs on a baffling problem: how to put four digits in a grid so that the four horizontal and vertical numbers add up to 100.

“How is this possible? Let’s think.” “That makes 98. We’re close – perhaps if we just change this….” “Oh I think I’ve got it!”

It’s not just this class where maths enthusiasm is rife. Over in Year 3, they are technically doing algebra – although that’s not what it is called. Numbers are replaced by pictures and the children are using their powers of deduction to solve puzzles.

In Year 5 they are trying to work out which tiles are missing from a set of dominoes. The children are immersed in working out the steps of the problem, trying out possible solutions. Discussion and suggestions abound. No ideas are dismissed.

Larkswood Primary Academy in Waltham Forest on the edge of London is one of several hundred schools in England and Wales that took part in the Week of Inspirational Maths at the beginning of last term.

It was an idea developed in the US by British-born Professor Jo Boaler, who is based at Stanford University and is the co-founder of the online maths community youcubed.org. The charity National Numeracy helped to organise the British week and schools were offered a full set of lesson plans and motivational videos designed to instil positive attitudes towards maths in their students (and teachers).

Number crunching

Jo was in the UK recently to spread the message that a revolution is needed in maths teaching. I caught up with her at ‘The Great Maths Con!’, a conference run by Herts for Learning, where she was enthralling teachers with demonstrations of open-ended lessons and her emphasis on the importance of learning from mistakes – of children’s brains actually developing through wrong answers.

“A lot of classrooms use maths as a performance subject, not a learning subject,” says Jo. “Children are only there to get the answers right. A six-year-old once said to me that maths is too much answer time and not enough learning time. Teachers need to change the classroom culture to openly value mistakes.”

Jo is a fierce opponent of setting in maths, and is keen to counter the closed mindset that she says can take hold very early that persuades children they ‘can’t do maths’. “We know children develop maths anxiety by the age of five – they pick that up from home and school. And putting them into sets in primary school is giving them the ultimate fixed mindset.”

Through promoting a week of inspiring lessons at the beginning of September, Jo’s aim was to set schools on the right path for the whole school year (the materials are still available free on the youcubed website for anyone who missed the boat). At Larkswood, the lead practitioner for numeracy, Deborah Haworth, was already familiar with the Boaler approach, with its emphasis on collaboration and discussion, on ‘low floor, high ceiling’ problem-solving where there is not always a single right answer and on persuading all children that they can do it – that the world is not divided into maths people and non-maths people.

“The principles weren’t alien to us. We were already doing a lot of investigative work in regular maths lessons,” she says. “But the kick-start to the school year was fantastic.”

Deborah says the week fitted in with their longer-term aims of giving the children solid understanding and mathematical fluency. “They are using their learning powers to ask ‘what links are we making?’. We don’t want children skimming over the surface. They have to understand in a much deeper way.”

Year 5 teacher Becky Collett said the week definitely raised the children’s engagement and confidence. “The children now know it’s OK to make mistakes. And they loved the idea of thinking deeply rather than quickly. That busted a myth for some some of them because they thought it was good to be fast.”

All adds up

Another school that took part in the week was St John’s Primary in Penistone, South Yorkshire, where the deputy head Ann Farr saw a noticeable change in attitude among the children. “It really stuck with them that you can get better and learn from your mistakes – that you’re not just born a mathematician or not.”

This was very pertinent later in the term when the children helped to correct their own practice test papers. “If they got something wrong, was it just a mistake or did they not understand something?” said Ann. “If the latter, what can they do about it? This is as important as the test itself.”

Even though she’s a former secondary maths specialist herself, Ann says that some of her staff were initially sceptical about the value of the week, because the resources seemed so open-ended. “But when they did the lessons, they could see that you could take the ideas as far as you want,” she said. “I think they were really inspired. Parents needed convincing as well. Their own experience of school maths is very much that it’s right or wrong, and that you’re put into sets. We don’t do setting but we do take the less-confident children, and try to build their knowledge and proficiency in year 6.”

At Larkswood they were already using a range of resources – whatever fits in with their overall approach. One firm part of the school day is a technique called Morning Maths Meeting, developed by the former Ofsted maths lead, Lynn Churchman, with National Numeracy. This involves a 10-minute maths session in every class, first thing each morning. It gives the children a short, focused period of maths to reinforce the learning in their regular classes.

“They might, for example, have two minutes on halving and doubling, feeding back really snappily,” says Deborah Haworth. “It’s the intensity of it – and the repetition, that really helps. Or, you might throw up a shape and say ‘tell me everything you know about it’. Or ask ‘which is the odd one out – 9, 27 or 64?’ And there’s always going to be more than one answer, so the children are explaining their thinking, they’re sharing their methods and improving their ability to talk about maths.”

Larkswood’s test results have shot up since taking part in the Week of Inspirational Maths. In 2012 79 per cent of children reached Level 4 in maths SATs, while in 2015 it was 91 per cent. “The children’s confidence has massively improved – particularly with the girls,” says Deborah. “Many of the girls used to just sit there, not wanting to compete. But now there’s a lot of sharing, a lot of talking to your partner, so they’re more involved and engaged.

For Deborah, there is a personal resonance in all this. “I have mild dyscalculia, and I share this with the children. I’m always making mistakes on the board because I invert my numbers. I had no confidence with maths till I was 16 .”