STEM education – Downloads, activities and ideas for teachers

What does STEM stand for and how can you implement it in the classroom? Find out here…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Most teachers will be somewhat aware of the importance of STEM education, but you may be looking for guidance for how best to implement it in your school.

The good news is, you don’t need to be an expert in the vein of Albert Einstein or dedicate huge amounts of time and resources to it. Read on to find out more.

STEM subjects

What does STEM stand for, you may be asking? The acronym stands for:

- science

- technology

- engineering

- mathematics

What is STEM education?

STEM education is all about connecting classroom activities and experiences to real-life opportunities. Instead of treating science, technology, engineering and mathematics as separate subjects, it’s a cross-disciplinary approach that is all about solving problems.

For instance, the problem might be that you want to create more habitats for bugs and insects on your school grounds. Pupils will then have to investigate where minibeasts like to live, and come up with a suitable solution.

It might seem strange to start preparing very young pupils for their future careers, but making real-world links is really important.

“STEM education is all about connecting classroom activities and experiences to real-life opportunities”

A STEM education introduces children to the idea that mistakes are normal and, in fact, can be seen as a positive because they help you to move on to something greater.

Still wondering “What is STEM education and why is it important?”. This video will give you a quick overview.

STEM education UK strategy

While we’re all aware of the importance of STEM learning, there’s currently no mention of it in the primary or secondary national curriculum for England.

Many schools teach it outside the curriculum via a STEM club. This doesn’t have to run all year, or even every week, and might incorporate any aspect of the subject, from gaming to growing vegetables.

Once your club is extended, you can enter pupils into national competitions or challenges.

STEM education and training strategy for Scotland

The Scottish government published its STEM Education and Training Strategy in 2017.

It aimed to expand and improve STEM education in schools by supporting a three-year £1 million fund to boost primary science learning and providing funding for CPD, among other strategies.

Read the third annual report on progress with the STEM Education and Training Strategy.

STEM Club ideas

This advice from Lynn Nickerson DPhil, STEM coordinator and science inclusion mentor at Didcot Girls’ School, will help you make sure your STEM Club ignites a spark among your students…

Start simple

Base your initial sessions on tried and tested activities. Once the students are hooked you can get more adventurous.

When you are ready, try some activities where you don’t know the outcome. Now you are doing real science and you and the kids can experience the thrill of making your own discoveries.

Some great activities to try at STEM Club are:

- Egg drop – Build a light and strong capsule to protect an egg when it’s dropped from a height.

- Fire writing – Paint a simple shape onto a paper towel using sodium nitrate (V) solution. When the writing is dry, press a glowing splint to the start of the shape to reveal its outline.

- Invisible ink – Write a message in invisible ink and reveal it using a special solution.

- Popping hydrogen – Collect some hydrogen gas in a test tube and make it ‘pop’ using a lighted splint.

- Disappearing magnesium – Use a small piece of magnesium and some dilute hydrochloric acid to make a one-minute timer.

- Sodium alginate shapes – Pour or squirt a viscous liquid into a fixing solution. It will set and form amazing shapes.

- Light-up games – Make a quiz where a light shines when you answer correctly.

- Helicopter challenge – Create a simple helicopter which will fall as slowly as possible.

- Sand and rice separator – Design and build a hand-held device to separate rice and sand.

- Tower challenge – Build the tallest tower you can that will support a 100g mass.

Find detailed instructions for all of Lynn’s suggested STEM Club ideas in our free guide.

Don’t do everything yourself

Don’t try to do everything yourself or running the club can become a burden. Involve technicians, colleagues, parents, older students or STEM Ambassadors.

Never do anything a student can do – they can take a register, carry equipment, write on the board and clear up. It should become their club – not just yours

Show your enthusiasm

Your enthusiasm will rub off on the students so join in with the activities, get to know the kids and enjoy STEM together.

Remember that mishaps will happen

If something goes wrong or doesn’t work, help the students to work out why and then have another go – that’s what scientists and engineers do.

Always have some spare supplies handy. Students will make more mess than you think, spill things and use up all of whatever you put out. Always do a risk assessment. Then get hands-on and have fun!

How to set up a STEM Club

Roderick Hamilton, STEM school liaison officer at the Museum of Science and Industry offers advice for setting up a STEM Club at your school…

Let’s first address the common misconception about what a STEM club actually is.

Any regular activity being run outside the curriculum counts as a club. The club doesn’t necessarily have to run all year, or even every week, and the subject can incorporate any aspect of STEM education, from gardening to Minecraft.

Running a STEM club can help your students to:

- Hone their skills and confidence in the subject you teach through hands-on activities

- Broaden their horizons and explore outside the curriculum – some-11 year-olds just want to learn about relativity NOW

- Improve social skills and relationships with staff and their peers

- Develop supportive relationships across age divides

- Find a happy place, for those with difficulties relating to other students

Running a STEM club can help teachers to:

- Take pleasure in your subject area. All the great fun activities you don’t have time to do in the classroom? Do them in a club!

- Raise the profile of the department, or even the school, by taking part in national competitions or applying for funding

- Collaborate with and learn from other staff from across the school

This is all great and hardly surprising to most teachers, but practically, setting up a club needs to be easy and fuss-free. Here are some top tips for success:

Don’t go it alone

By working across departments you will not just share the planning load, but also show students that maths is a part of science, engineering a part of computing, and that these skills work in harmony in the workplace.

When St Mary’s Catholic High School in Wigan launched a new STEM club, the technology department was initially going to run the club solo. However, thanks to reaching out to the science department, it now has a co-leader who can share planning time, and another set of technician’s stores and expertise to dip into.

Make it student-led

At St Anne’s RC High School in Stockport, the students research STEM topics of their own choice, and then present them to the club to provoke debate and discussion.

The role of the teacher is to mediate, support and challenge, rather than prepare content for each session.

Once you have a core audience for your club, see if they want to pick the content and lead on developing projects. Levenshulme High School in Manchester takes this even further and had over 80 applications for just 24 places to become ‘STEM Leaders’ in school.

This prefect-like student role sees students performing admin and preparation for STEM clubs, mentoring younger students, and generally leading on raising the profile of STEM in school.

Link up with industry

Whilst you might not find a volunteer to run your club for you, there are STEM Ambassador Volunteers nationwide who give up their time to support STEM activities.

All Hallows RC High School in Salford invited a STEM Ambassador into their Digital Leaders club to support students’ coding projects.

At the same time as helping with the activities, the STEM Ambassador gave insight into real-life careers and highlighted the relevance of the students’ work.

Make use of resources

Practical Action’s STEM activities offer great real-world problems for students to solve.

The James Dyson Foundation Challenge Cards are a massive hit with teachers – 44 activities in one PDF.

STEM learning

A play-based, or scenario-based, approach can be an effective way to teach STEM. Pupils should be enabled to lead their own investigations, following their own particular interests.

Nicola Connor, a primary teacher at Peel Primary School, suggests giving pupils the chance to investigate resources and materials before you use them in your lesson. Ask pupils what they think they are going to be learning about before formally introducing the topic. Touching, feeling and observing will all help pupils to learn.

A play-based approach to STEM learning is a great way to get children engaged, as they’ll all want their ideas to be heard.

Andy Snape, assistant head at Newcastle-under-Lyme College, suggests that playing Minecraft and building LEGO are both excellent examples of children engaging with problem-solving, hands-on activities, describing them as “having a foot in both camps of play and learning.”

STEM activities and STEM projects

A background in a STEM subject is not necessary for being a great STEM educator. All you need is a real-life question or scenario to get things started.

When trying STEM-based activities in the classroom, try and keep your task input to a minimum. This gives children the chance to come to their own decisions about how to solve the problem they’re faced with.

Even though it’s hard, try and stand back and let pupils make mistakes as they work, offering additional information where necessary.

STEM activities don’t have to be lengthy science projects. Quick tasks, such as using marshmallows to build an igloo or building effective paper aeroplanes can be completed in less than 15 minutes.

Save time by linking activities to curriculum topics. For example, build a pyramid for a pharaoh out of spaghetti and marshmallows. Alternatively, do an activity in maths that also covers science objectives.

If you feel unsure about teaching STEM, ask an expert to visit your school. Museums, zoos and universities are often keen to promote the topic to children for free.

Free teacher CPD

We’ve put together four CPD packs for teachers of STEM, each packed with information, ideas and inspiration from education experts and current teachers. Download them in just one click.

- Create greater enthusiasm for STEM in your school and teach it in a coordinated way

- Hear from real secondary teachers about how they’re boosting STEM learning in their schools

- Help secondary students prepare for the careers of the future by getting them hooked on STEM subjects

- Learn how to equip your secondary pupils with the skills that STEM employers are looking for

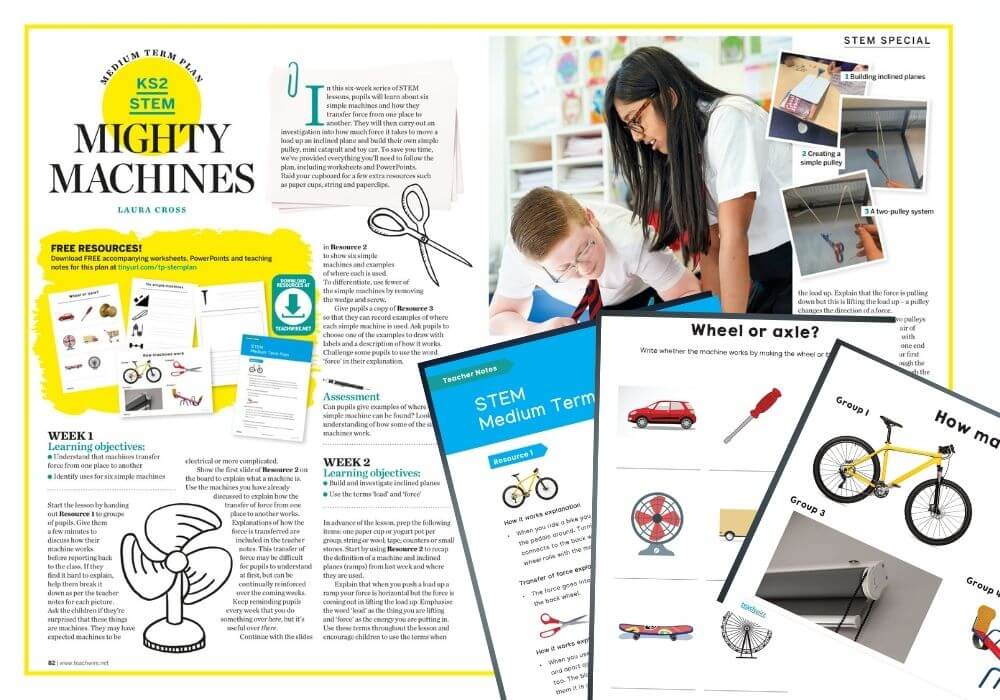

KS2 forces STEM activities

Download a free six-week series of STEM lessons. Children will learn about six simple machines and how they transfer force from one place to another.

The download contains a PDF medium-term plan, worksheets, PowerPoints and teaching notes.

KS2 Victorian Inventions resource pack

Use this free KS2 STEM resource pack to help pupils:

- Understand that inventions are all around us and that invention is a way to create solutions to problems or challenges

- Identify potential problems/areas where an invention could be useful

- Make hypotheses and evaluate their invention ideas

- Familiarise themselves with inventions from a different era such as the Victorian era and how they relate to the present

KS2 engineering worksheets

Use the fast-paced, action-packed story EngiNerds by Jarrett Lerner to explore a range of STEM activities. Use these free activity ideas and worksheets to draw your own robot, come up with alternative uses for everyday objects, and invent a gadget.

Minibeast habitats

Here’s an example from Jane Dowden, education innovations manager at the British Science Association, of how a STEM activity might work in practice...

The problem

We want to create more habitats (natural homes) for minibeasts in our school or local area. In this challenge you need to investigate what kinds of habitats minibeasts like to live in.

The real-world context

It’s important to protect our local environment and its biodiversity. There are wildlife habitats all around us. We can help to protect these habitats and create more of them if we know about the kinds of places minibeasts like to live.

The materials and resources

- Magnifying glasses

- Paper, pencils and clipboards for recording

- Camera to take photos of different habitats (optional)

- Pictures of minibeasts to help identify them

- Container to collect minibeasts (optional)

- Safe access to the outdoors

What to do

- Begin by introducing the activity and the problem they need to solve, perhaps beginning with a story to set the scene

- Discuss the areas they might look and the minibeasts they might find when they are outside

- Give out the resources and discuss how they can use them to help their investigation. Discuss how they will keep themselves and any minibeasts safe

- Before they begin, ask children to think about how they will record their results – this could be via note-taking, drawing or photographs. Results might include what they have found as well as where they found it and a description of the habitat

- Back in the classroom, ask the children to present their findings to the rest of the class. They can be as creative as they like with their presentations. Use the facilitation questions below throughout the activity to help children think through the problem

Questions

- Where could you look for minibeasts?

- What types of minibeasts do you expect to find there?

- How will you make sure you don’t harm them?

- Can you describe the places you found the most minibeasts?

- What kinds of habitats do minibeasts like to live in?

- Why do you think this is?

- How could you create more habitats for minibeasts?

Ensure children are supervised throughout the activity and risk assess the outdoor areas children will be investigating. Children should wash their hands thoroughly after exploring outside and handling minibeasts and don’t forget to ensure any minibeasts collected are returned where they were found.

Gingerbread man escape

Here’s another idea to try, from primary teacher and author Emily Hunt.

Explain to the children that a gingerbread man has escaped the oven and needs to cross a river to get away. Can pupils help build him a bridge?

Activities do not need to involve expensive resources. The following ideas from Emily are all cheap options:

- Make a marble run from cardboard tubes cut in half

- Create an egg parachute from carrier bags

- Make a boat from tin foil

- Create bottle rockets from plastic bottles filled with vinegar and bicarbonate of soda

- Secure lolly sticks to plastic spoons to make catapults

Play-Doh elephants

Primary teacher Nicola Connor suggests the following playful way of teaching forces, thought up by Gaynor Weaver.

In pairs, ask children to one at a time create elephants from Play-Doh, but during each attempt, they must only use one force, such as twist, pull or push.

This helps pupils to see the effect a force has on an object but also allows them to practise listening and talking.

More 15-minute ideas

Try the below ideas from Emily Hunt’s book, 15 Minute Stem, published by Crown House Publishing...

Paper plane bullseye

Fold a sheet of paper to create a plane. Place a short-range target 5m away and a long-range one 10m away.

Begin testing your plane with the short-range target, refining your design to make it land as close as possible. Then create a new plane and aim for the long-range target.

Spend time refining your plane to make it more accurate. Look at the most successful designs for each target. Why did they work best? How do the short- and long-range designs differ?

Throwing the plane creates a force that propels it forward. Real planes have engines to create thrust. Drag is a force working in the opposite direction.

The thrust has to be greater than the drag for the plane to advance. Gravity acts as a downward force on the plane.

This is balanced for a time by the wings, which experience lift (an upward force) as the air passes over them. The balance of these forces determines the journey of the plane.

Marshmallow towers

Give pupils mini marshmallows and toothpicks and ask them to build the tallest tower they can, focusing on a particular shape such as triangles, squares, rectangles or pentagons.

Use 3D shape words such as ‘cubes’, ‘cuboids’ and ‘prisms’. Triangles are inherently rigid so will probably make the most successful structure.

Investigate how triangles are used in famous architectural examples such as the Eiffel Tower.

One-shape structures

What is the tallest structure we can make using only one shape?

Decide the shape you will use (triangles, squares, rectangles, pentagons) and then start the 15-minute timer.

Use mini marshmallows as joins to dig toothpicks into. Double up the toothpicks for extra strength. Measure your structure to see how tall it is.

Encourage older children to discuss their structure using 3D shape vocabulary such as cubes, cuboids, triangular pyramids and prisms.

A successful structure will probably include triangles in the design as they are inherently rigid. This means when we apply a force they don’t change their shape.

In contrast, when we apply a force to a shape such as a square, it can be deformed into a parallelogram.

Civil engineers and architects are often asked to create tall structures and must think carefully about their foundations and shape.

Find out more about how triangles are used in architecture. A famous example you could research is the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

Camouflage nature walk

How do animals protect themselves from predators? Head outside for a brief nature walk. Look carefully for camouflaged animals.

Try looking at tree trunks, leaves, flowers and leaf litter. Use a magnifying glass to look at each example of camouflage. Then take a photo.

When the time is up, review the findings and count how many examples you photographed. You can also try going to a different environment (such as forest, pond, urban) to find different examples.

Looking closely at our natural environment, we can find lots of examples of animal camouflage. This helps these animals to blend into their surroundings, protecting them from predators.

Examples that you may have spotted are a grey squirrel against tree bark, a moth on a wall, or dark-coloured insects in the undergrowth.

Engineers and designers often take ideas from nature when creating new things. This is called biomimicry.

Research how the military has used camouflage inspired by nature in its clothing and in its designs for vehicles and planes.

Trending

Bridge-building ideas for EYFS-KS2

Here, Laura Cross of Inventors & Makers suggests simple STEM ideas that use accessible resources and need minimal prep time.

Download accompanying worksheets for this activity.

EYFS

Resources: Pile of hardback books; small world characters or animals; two classroom chairs.

Activity:

- Place your small world characters or animals on one chair with around a 15cm gap to a second chair.

- Ask children what could help the character cross from one chair to the other. You can add a narrative to this with water/trolls below etc.

- Once you’ve discussed the idea of a bridge, ask them to use books to build a bridge. They will likely place one book across the gap and you can show the character successfully crossing.

- Next, move the chairs further apart and ask them to make another bridge. This time they’ll need to overlap the books to create a bridge.

- Let children work in small groups to see who can make the widest bridge from books and extend by adding a requirement to support a certain weight or number of characters.

Engineering thinking: Pupils will be investigating and testing the type of books that work best, how best to balance the books, the need to weigh down the ends of the books, as well as measuring and counting distance and weight.

KS1

Resources: Selection of junk modelling materials such as straws, craft sticks, paper cups, cardboard; tearable tape (e.g. washi tape); scissors.

Activity:

- Start by creating a river that a bridge must cross. You could tie this in with the Three Billy Goats Gruff story to add a cross-curricular element. Make your imaginary river from a piece of material, sheets of A4 or some exercise books. Make your river around 20-40cm wide.

- In small groups, give pupils a selection of junk modelling resources to build a bridge to cross their river. You might demonstrate how they can join the materials with tape, but don’t give any bridge ideas yet.

- Give pupils time to build, sharing good models with the rest of the class and building on ideas where necessary. This works best when you don’t give any ideas to start with so each group thinks of their own bridge design. You’ll be surprised at their creativity!

- If pupils build their bridge successfully, tell them it also needs to support a minimum weight, made up of some coins/counters/ bricks etc. Give them extra time to improve their bridge to add strength.

- Give pupils the KS1 engineering bridges worksheet to record their bridge design and materials used.

Engineering thinking: Pupils will plan, design, build and test structures making constant improvements and iterations to solve problems that arise.

KS2

Resources: Sheets of A4 paper, piles of chapter books, glue sticks, small weights such as coins, counters or blocks.

Activity:

- Create two piles of books of the same height, at least 5cm high. Measure a 15cm gap between the books and demonstrate to pupils they need to create a paper bridge to cross the gap.

- Place one sheet of A4 paper as a bridge and then add your small weights one by one to the centre of the bridge to see how many it can support before buckling. Don’t hold or weigh down the ends of the bridge, to show it won’t support much this first time.

- Next, tell pupils in small groups they must make a bridge to support the most weight they can using only two sheets of A4 paper. They can fold and/or glue their paper in any way they like. Give them time to investigate different ways of folding the paper, sharing good models and suggesting ideas where necessary. They can use the KS2 paper bridges worksheet to record their designs and the weight each bridge supported.

- If necessary, after a few minutes suggest that folding the edges of the bridge up like a handrail on each side will work well and they can investigate different heights for the fold.

- Give a set time to see which group can build the strongest bridge and then share and discuss the results.

Engineering thinking: Pupils will investigate by planning, designing and testing different bridge constructions and thinking about how the same material can be used in different ways to impact its strength.

Women in STEM

From a young age, children develop perceptions about certain jobs. Introducing STEM jobs to pupils is a great way to dispel gender stereotypes and widen children’s career aspirations.

Studies have found that it is a lack of confidence, not ability, that can discourage young women from taking STEM subjects. As a result, the percentage of women in the UK STEM workforce is low, at only 15%.

The good news is that in 2022, overall STEM entries by girls overtook boys slightly (50.1% female vs 49.9% male). More girls than boys collectively studied biology, physics and chemistry at A-level.

Educational writer John Bolton is calling on teachers to be role models and provide plenty of opportunities for girls to see women in STEM. He suggests talking about:

- computer scientist Margaret Hamilton

- mathematician Ada Lovelace

- computer scientist Grace Hopper

Other women in STEM that you can talk to pupils about include:

- Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell, who discovered the first radio pulsars

- businesswoman Martha Lane-Fox

- YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki

Amy Ryan, head of science at Harris City Academy Crystal Palace, set up a STEM club for female students at her school. The girls were tasked with STEM challenges such as creating a simple water distiller, a female-friendly backpack and washable sanitary products.

One participant said that she was “starting to learn and embrace lots of new skills I never thought I had in me.” Find out more about STEMgirls club.

Learn how to start a STEM club for girls, identify girls with STEM potential and encourage girls to participate in STEM and coding with this free CPD pack.

Best STEM education blogs

- Visit the Vivify STEM blog for STEM activity ideas, distance learning activities and teaching tips.

- Education Scotland’s STEM blog provides information about the latest news, events and resources to support STEM learning.

- The Scientix blog features stories from science educators across Europe.

- Head to the All About STEM news page for updates about awards, competitions, events and more.

STEM education facts

If you’re looking for STEM education fun facts to share with pupils or colleagues, take a look at the below statistics:

- By 2024, around 2.5 million jobs requiring science, engineering, technology and research skills will need filling (Tomorrow’s Engineers programme)

- Engineering accounts for 25% of gross value added for the UK economy (Royal Academy of Engineering)

- 32% of primary pupils agree that they worry about science lessons being “too hard” (2019 survey conducted by the Wellcome Trust)

STEM education quotes

“Creativity is the secret sauce to science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). It is a STEM virtue.”

Ainissa G. Ramirez, PhD, former engineering professor at Yale University

Millions saw the apple fall, but Newton asked why.”

Bernard Baruch, American financier

“The role of the teacher is to create the conditions for invention rather than provide ready-made knowledge.”

Seymour Papert, South African mathematician and computer scientist

How to make your curriculum go above and beyond

We hear how an ambitious inter-school STEM initiative helped one school in the North East bolster its already extensive science offer…

Here at St Leonard’s Catholic School, we attribute our success in science to the holistic approach we take to the subject. We don’t demand an ‘exam factory’ mentality of our students, but we do believe in equipping them with all the attributes they’ll need to enter STEM fields.

As a department, we have agreed ‘non-negotiables’ with regards to our curriculum, teaching and learning principles. We don’t see our curriculum as the contents of a textbook, an exam board specification list or a series of subject content points on the National Curriculum. It needs to go above and beyond that.

‘Science capital’

Our results have always been driven by the ability of our staff to deliver an ambitious curriculum, with further continuity provided by extracurricular clubs that have developed over time. These include our KS3 Science Club, KS4 Mini Bio Society, Sixth form Chemistry, Biology and Medical societies, as well as our Physics Surgery.

We also run additional A Level mentoring sessions and reading groups, which have helped to boost students’ engagement with science subjects and encourage excellent uptake at A Level.

Our department’s aim has always been to ‘Provide the best science experience, to produce the best future scientists.’ To achieve that, we’ve sought to develop our students into great scientists who:

- Think scientifically

- Possess a scientific skill set

- Can apply logic to real-life scenarios

- Transfer their science skills across other subjects

- Can ask insightful questions

- Demonstrate enthusiasm for the natural world

- Are keen to know more

We’ve seen sustained academic success over the past five years, but still recognise the importance of regularly evaluating what we do and seeking out areas for improvement – particularly in relation to changes across the educational or employment landscape.

Following a recent audit of our curriculum, teaching and learning principles, we felt it wise to enrich our STEM opportunities with a focus on careers guidance. This initially led us to review our understanding of the Gatsby benchmarks and ‘science capital’.

The term ‘cultural capital’ was originally coined by the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who described it as “The cultural knowledge that serves as currency that helps us navigate culture and alters our experiences and the opportunities available to us.” Building on that notion, ‘science capital’ could be summarised as the knowledge, attitude, skills and experiences our students develop over the time they spend with us.

As a department, we’re confident that we’re able to deliver on the following areas:

‘What you know’ – through our challenging curriculum and regular use of Rosenshine’s principles and effective recall strategies

‘How you think’ – via cognitive and metacognitive approaches in our T&L practice, promotion of growth mindsets and igniting of students’ curiosity

‘What you do’ – through our delivery of disciplinary knowledge, teaching the skills required by scientists to hypothesise and problem solve, and by giving pupils as many opportunities to experience practical science as possible.

There has, however, been a key piece of the puzzle missing – namely ‘Who you know’. This has proved to be a difficult component to fulfil here in the North East of England, where science-based opportunities and experiences are somewhat limited. Or so we thought.

Unmissable opportunity

Our efforts to address this gap is what first led us to become involved with an ENTHUSE Partnership. Since September 2022, St Leonard’s has been the lead school for the ENTHUSE Partnership within our trust, the Bishop Wilkinson Catholic Education Trust, under the direction of its director of science, Rob Swinney [see panel below].

ENTHUSE Partnerships are collaborations between eight to ten schools or colleges, supported by £25,000 of funding over two years. Each Partnership involves drawing up a tailored two-year action plan that typically includes teacher CPD combining residential, local and online courses; free curated and quality-assured resources; engagement with STEM Ambassadors to inspire young people; and the development of STEM clubs to further engage young people and improve their practical skills.

We’ve endeavoured to invite local STEM providers who can give us better insights into the learning and networking opportunities on our own doorstep. Josh Minto, from the RTC STEM ambassadors hub in particular, has been consistently willing to attend and share some local STEM leads.

When he told us about Space Camp 2023, we felt it was a ‘science capital’ opportunity not to be missed. It’s well-documented that the north east of England is currently experiencing a STEM skills workforce gap, making it vital for our young scientists to be introduced to and involved in such opportunities as and when they arise.

The Space Camp 2023 event was held over five days during half term at Sunderland University campus, as a joint venture between The National Space Academy, and sponsors Lockheed Martin and Viasat. It provided our students with an immersive experience themed around space activity, and opened up whole new vistas for them – significantly boosting their technical and academic understanding, while also highlighting potential pathways for career progression in the UK space sector and other civil and military space-related domains.

There were a range of high-profile guest speakers and representatives of the space sector at the event, there to present to and work alongside our students. As one of our students, Zachary Bremner, remarked afterwards, “Space camp was really interesting and insightful. My favourite part was meeting enthusiastic representatives of the space industry. I intend to contact Lockheed Martin and Viasat with a view to work experience. My career aspirations to enter the space industry were consolidated by this camp.”

Another of our students, Katy Hill, said “I loved it! My favourite part was going to Sunderland University to look at different robots and learn how they’re used in space. It helped me learn more about the space sector and what jobs are available to me, and I’m happy that I made some good friends who share my interests and are doing the same A Levels as me.”

Rewarding and inspiring

As a department, we’ve sought to utilise the professional CPD available via the ENTHUSE partnership including:

- ‘Stretch and Challenge in Science’ department CPD

- Attending the Secondary Science Teaching and Learning conference in York

- Developing health and safety awareness among our science teachers

STEM ambassadors attending our school career events have also gone on to provide further CPD at our ENTHUSE meetings. It was they who introduced us to the annual STEM Fest event, which some of our triple science students attended last July and found to be a rewarding and inspiring experience.

This year we’re hoping to participate in STEM Learning’s Research Placements and Experiences programme. The opportunities are certainly there, once you know where to look.

Aisling Stewart is head of science at St Leonard’s Catholic School in Durham.

Get it together

Rob Swinney explains more about the ENTHUSE Partnerships and how they work…

How did the Science Hub Learning Partnership come into being and what does it do?

For many years, Cardinal Hume Catholic School has run one of the highest performing Computing Hubs in the country on behalf of STEM Learning. We felt we could emulate this success across other subjects, and accepted the Science Learning Partnership contract in the summer term of 2022.

The SLP provides high impact, quality assured science CPD for teachers at all experience levels and bespoke school-to-school support, while also leading ENTHUSE Partnerships, which bring schools together as clusters to work on specific aims.

To what extent have the goals and approaches adopted by the Science Hub changed or evolved over time?

The teacher recruitment and retention crisis has hit science departments particularly hard. Where once it was difficult to hire a qualified physics teacher, the problem now persists across all three sciences.

Schools are having to adapt, and so the SLP has come to focus on delivering subject knowledge enhancement courses to upskill non-specialists to fill gaps, or allow science teachers to deliver across specialisms. We also now provide courses to support ECTs, assist their development and keep them in the profession.

Can you point to any specific examples of impact or outcomes as a direct result of the SLP’s work?

We’ve worked with numerous schools across the North East, many of which have subsequently had Ofsted inspections with deep dives in science, and we’re proud that every one of them achieved at least a Good rating. Our ENTHUSE partnerships have provided CPD to staff, introduced them to novel ways of teaching science and provided a whole host of resources for them use in schools – from air pressure rocket launchers, to steamboats and inflatable flying sharks.

5 myths about teaching STEM

Primary school teacher and author Emily Hunt sets out some misconceptions about teaching STEM, and why they shouldn’t hold you back…

Think of some of the fastest-growing industries in the world today: renewable energy, biotechnology and software engineering.

The necessary skills for these jobs all come under the banner of STEM. Does our education system lag behind the rapid economic developments across the world?

STEM education is an inspiring way of connecting educational experiences to real-life opportunities.

Instead of teaching science, technology, engineering and maths as separate subjects, STEM is a cross-disciplinary approach with problem-solving at its heart.

While we are increasingly aware of its importance, with no National Curriculum for STEM education, how do we implement it in the primary classroom?

Here are some of the most common myths about STEM education, busted!

Myth 1 | You need to be an expert to teach STEM

As a primary school teacher, we’re expected to be the jack of all trades, transitioning seamlessly between subjects as the school day goes on. Adding STEM education to the mix? Surely that’s a step too far!

While a background in a STEM subject will certainly give you an advantage in terms of confidence and subject knowledge, it is by no means a requirement for being a good STEM teacher. All you need is a real-life hook or question and you’re off!

Take this example: the gingerbread man has escaped from the oven and has come across a river. Can you build a bridge to help him cross it before he is caught?

STEM activities such as this do not require lengthy inputs or overly scaffolded resources. My advice is always to keep the task input to a minimum, allowing the children to explore the resources and reach their own decisions about how to solve the task.

Then challenge yourself to stand back and let the children make mistakes on their way to solving the problem, supporting where needed with additional instructions.

If you need activity inspiration, there are a growing number of books and online resources available. The STEM Learning Centre website (stem.org.uk) offers a range of activities and ideas aimed at the primary age range.

If you still feel a lack of confidence about tackling STEM, why not invite an expert in to visit your class? Consider reaching out to local places such as universities, zoos, museums and the STEM Ambassadors scheme – their 30,000 or so ambassadors volunteer their time and expertise to promote STEM to young people.

My past communications with them have resulted in a visit from a zookeeper, a boat-building demo on the school playground and a palaeontologist-led excavation activity, all completely free!

Myth 2 | STEM education is a big time commitment

With the demands currently placed upon the primary school timetable, I can barely squeeze in the time to chat to my class about their weekend, let alone fit in a weekly STEM education lesson!

The good news is that STEM education doesn’t need to be an additional burden on our already overstretched timetables. Indeed, I would argue that high-quality STEM education can be delivered in as little as 15 minutes.

Quick, engaging STEM activities are a great way to inspire and increase student motivation with the task at hand. Speedy challenges could include building an igloo out of marshmallows, creating a paper aeroplane to hit a target or making a miniature raft out of natural materials.

Making careful use of the cross-disciplinary approach can even cut down on workload and allow for greater flexibility. For example, using a maths slot to deliver a STEM activity could also cover your science objectives for the week. Linking activities to curriculum topics is another way to save time.

For instance, if you are teaching about the Egyptians, challenge your class to build a pyramid for Pharaoh using just spaghetti and marshmallows. You could set the additional challenge of specifying a pyramid height.

Myth 3 | STEM lessons are expensive to resource

School budget? With the current funding shortfall we practically have to justify orders for classroom stationery, let alone computers and expensive kits!

It may surprise you to know that some of the most effective STEM activities can be resourced from things you will already have in the classroom.

Take the challenge of building a newspaper tower: all you need is newspaper and tape! Granted, there are some fairly pricey educational kits on the market for STEM lessons.

However, plenty of exciting STEM activities can be resourced from the contents of your recycle bin. Here are just a few examples:

- Cardboard tubes cut in half make a fantastic marble run when stuck to a vertical surface.

- Carrier bags make a perfect parachute for an egg.

- Silver foil can be repurposed to create a tin foil cargo boat.

- A plastic bottle filled with vinegar and bicarbonate of soda makes an excellent bottle rocket.

- Lollysticks can be secured to a plastic spoon to make a catapult.

Myth 4 | STEM education is a job for secondary schools

At primary school level, we’re busy establishing the basic building blocks of maths and science. Children are far too young to be thinking about their future careers. Surely secondary schools can bring in the STEM stuff.

We’re all familiar with the stereotypes associated with STEM, namely the misconceptions of these subjects as ‘boring’ and ‘nerdy’ or the idea that they are ‘boy subjects’. The sooner we challenge this, the better.

While it may initially seem daft to begin preparing children for their future careers from as young as five, the importance of making real-world links from an early age is not to be underestimated.

Research shows that the perceptions children have about certain jobs and careers are formed at a young age and that gender stereotyping exists from the age of seven.

By introducing children to relevant STEM careers early on we can challenge these perceptions and stereotypes and widen their career aspirations.

Myth 5 | STEM is purely about science, technology, engineering and mathematics

What about those children that just aren’t interested in these subjects? How will lessons in STEM education be relevant to their future careers and aspirations?

STEM activities are designed to encourage curiosity and creativity, along with a wide range of other important soft skills that are crucial to success in STEM and other careers. Problem-solving, critical thinking, teamwork, communication, confidence, spatial awareness… the list goes on.

Likewise, the cross-disciplinary approach to STEM education can easily be extended beyond these subjects. Using a book as a stimulus for a STEM task is an effective way to make links with your English curriculum.

Many STEM activities are innately creative and artistic, making links with art. The context of your STEM activity could also be linked to a humanities topic or even a PE lesson.

Another fantastic justification for teaching STEM is the opportunities it brings us to develop a classroom environment in which mistakes made along the way are seen as positives.

When a child makes a mistake, encourage them to be kind to themselves and to realise that mistakes are normal, inevitable and important milestones along the way to something greater.

Even more STEM education ideas

If you want to improve your pupils’ STEM education, Google programme ‘CS First’ is a free computer science curriculum that anyone can teach. It’s designed for pupils aged 9-14 and will help children to collaborate on projects.

The Horizons in STEM higher education conference is an annual event that aims to help STEM teachers make connections, innovate and share pedagogy.

If you’re looking for publications on STEM education, the International Journal of STEM Education is a great place to start. Inside you’ll find lots of scholarly articles on STEM education, written by STEM graduates, researchers and professors, all of which have undergone peer review.

If you’re looking for STEM resources for your classroom, the Sillbird STEM 12 in 1 Education Solar Robot can be assembled into 12 different robots which can move on land or in water.