Climate change for kids – Best global warming teaching resources

Learn all about Greta Thunberg, Extinction Rebellion, the climate crisis protests, carbon emissions and more with these worksheets, lesson plans and other resources for schools…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Preparing pupils for a climate emergency may seem overwhelming, but teaching kids about climate change is a necessary step in building a more informed and proactive generation.

Use these ideas and resources to integrate climate change teaching across different subjects in your school. (We also have ideas for writing your own school climate action plan).

Teaching resources

KS1 climate change lesson plan

With a mixture of discussions and hands-on fun, use this KS1 climate change lesson to introduce children to the wonderful world of renewable energy. Watch as they come up with their own magical ideas to help the environment.

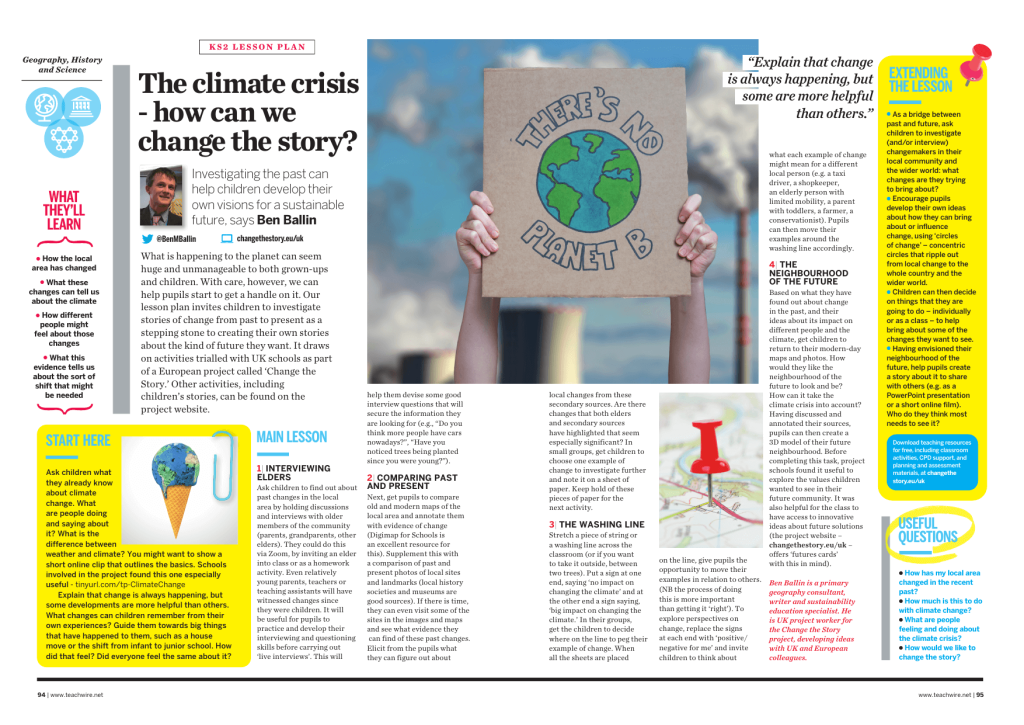

KS2 climate change activities

This KS2 climate change lesson plan invites children to investigate stories of change from past to present as a stepping stone to creating their own stories about the kind of future they want.

Greta Thunberg and climate change reading comprehension worksheets

Less than a year after her first protest, Greta Thunberg became one of the most famous climate activists in the world. This resource from literacy resources website Plazoom includes a five-page factsheet on Greta and her role in climate action. There’s also a 12-question worksheet for pupils to test their comprehension skills.

Climate change assembly

This climate change assembly from fuel poverty and climate charity, Centre for Sustainable Energy, takes about 30 minutes to deliver. It covers climate change, how it affects humans and animals and how young people can take action.

There are also free, adaptable climate change lesson resources from the Centre for Sustainable Energy. It will help you teach this important subject in primary school.

Worldviews and the environment

Why care for the environment? This KS2 lesson from Matthew Lane explores how different worldviews – including Christianity and ethical veganism – inspire people to protect the planet. With climate change and biodiversity loss shaping children’s futures, this topic has never been more important.

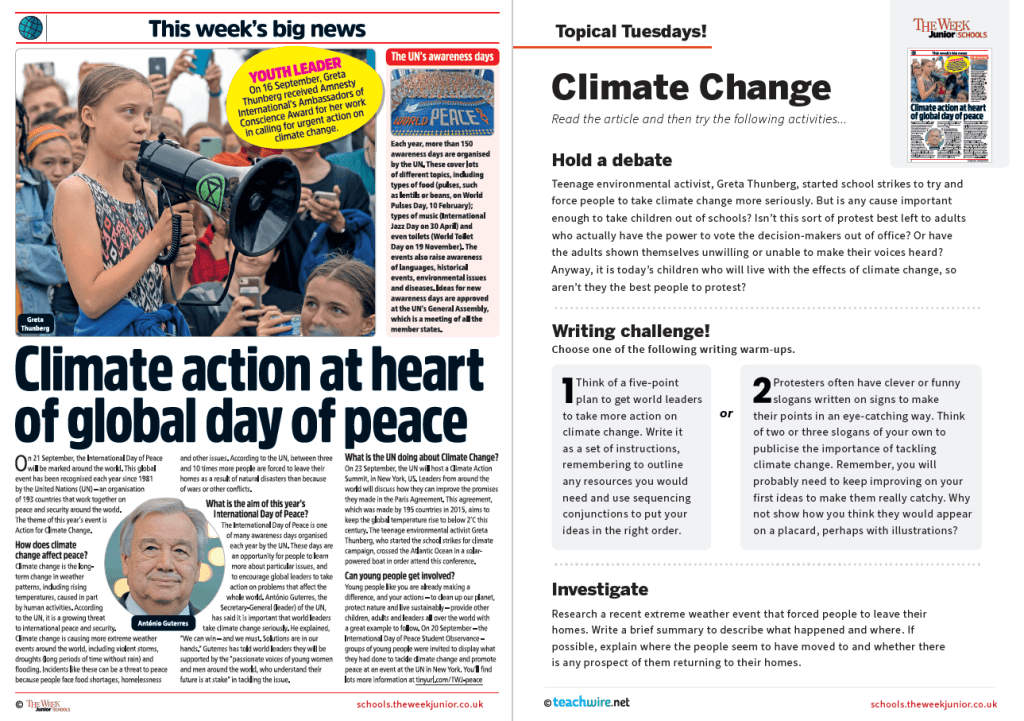

Greta Thunberg and climate protests

This free resource talks about the International Day of Peace and what its aims are. It also discusses how peace is affected by climate change.

There are four activities students can do, including writing a five-point instructional plan urging world leaders to make climate change an essential issue.

Protest pollution, fossil fuels and greenhouse gas with this art lesson plan

Show your class how to express what they feel passionate about in an artistic way, with Jasmine Smail’s art and PSHE lesson plan.

You’ll explore the activist, contemporary artist and writer Patrick Brill, known under his pseudonym Bob and Roberta Smith. It’s the perfect way to introduce your class to activist art.

Climate change activity pack

Originally created for Great Big Green Week, this resource pack supports climate education with curriculum-linked activities.

Pupils explore the effects of climate change, weigh up energy sources, consider the impact of consumer habits and take part in creative writing tasks on global warming and veganism.

Free ebook resource

Schools can download a free ebook called Children For Change. It features contributions from 80+ leading names in the UK children’s author community, including Liz Pichon, Charlie Higson, Axel Scheffler, Joseph Coelho and more. It aims to inspire the next generation to change their future.

The ebook covers KS2 curriculum topics including the causes, impacts and effects of climate change on the environment. It also covers weather patterns, biodiversity, heatwaves, renewable energy and sustainable practices.

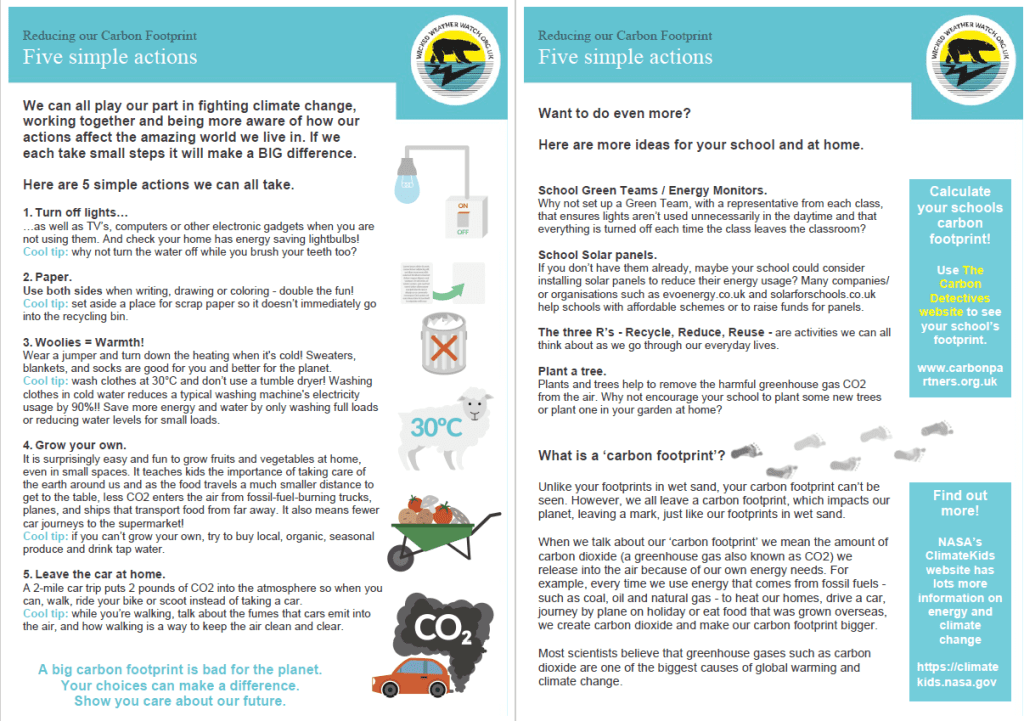

Five simple ways to reduce your carbon footprint

We can all play our part in fighting climate change. If we each take small steps it will make a big difference.

This PDF from Wicked Weather Watch offers five simple ways to reduce our carbon footprint. There are also some extra ideas to take it further in school or at home.

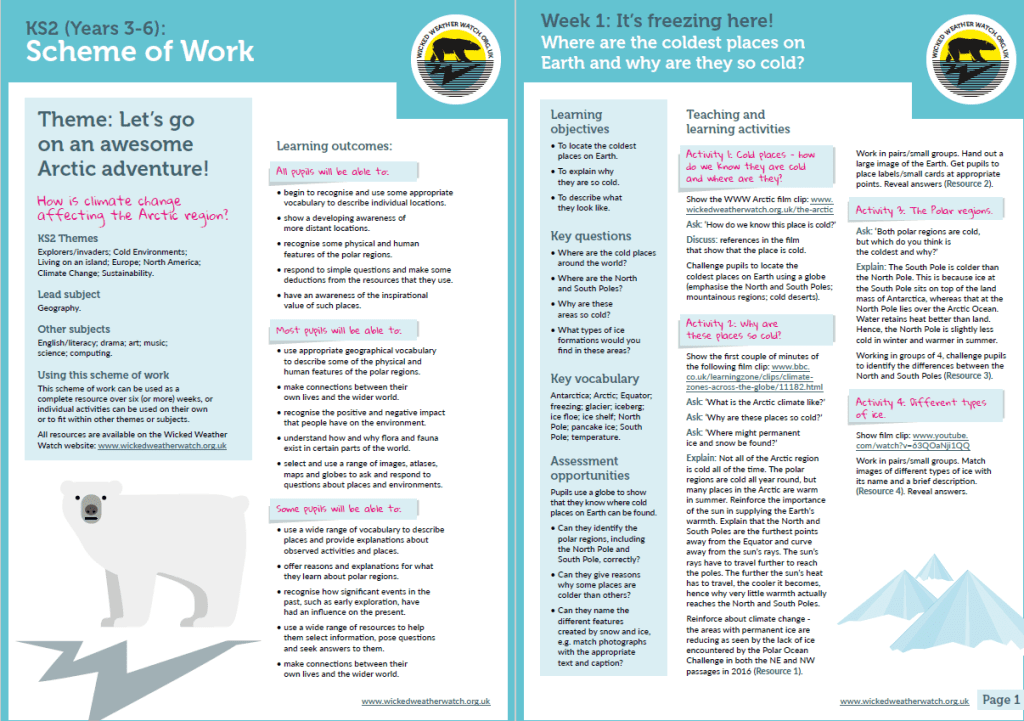

Climate change KS2 scheme of work

Wicked Weather Watch has also produced this KS2 scheme of work. Use it as a complete resource over six (or more) weeks, or do the individual activities on their own or to support teaching other themes or subjects.

WWF climate change activities for kids

The World Wildlife Fund has produced a range of curriculum-linked resources for the classroom to help your pupils explore the issues of climate change in an engaging and motivating way.

There’s Shaping our Future, which gives an introduction to climate change and what it is. Ends of the Earth looks at the poles. For getting involved with WWF events there’s Earth Hour and Green Ambassadors.

Climate change facts for kids – lessons and PowerPoint

In this suite of lessons from Young People’s Trust for the Environment, KS2 (or 3) students will learn:

- What is climate change?

- What impacts is climate change having around the world?

- How are humans causing climate change?

- What can we all do to stop climate change?

This lesson plan suite includes detailed instructions for a simple, but highly effective and engaging experiment that can be carried out using simple equipment in the classroom to show how increasing levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere are contributing to rising global temperatures.

Teaching children about Earth’s climate with hope

The best way to respond when children are scared is to offer reassurance, says Alex Standish, so our role as teachers is to encourage a more balanced narrative.

In this article he explains how you can teach climate change while presenting hope for our children’s futures and empower them to create a positive change.

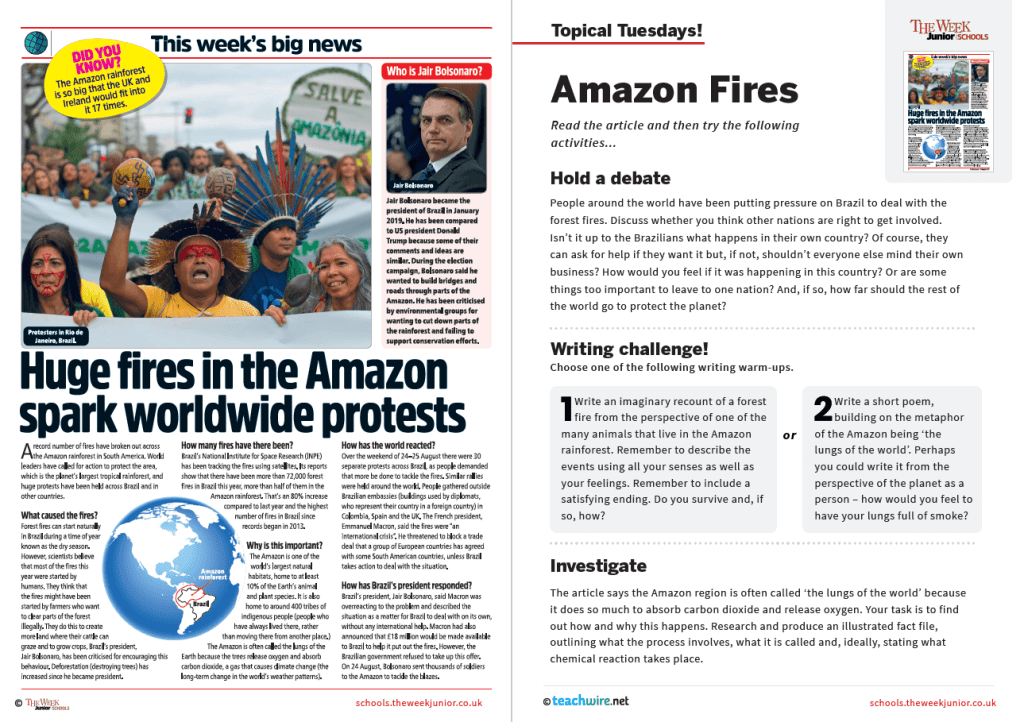

Amazon forest fires

This resource looks at devastating fires in the Amazon rainforest, and global protests to ensure their protection. Students will learn what caused the fires,, how the world reacted and how Brazil responded.

This PDF resource includes this article, as well as accompanying activity ideas:

- Hold a debate on whether other nations have a say in how these fires are dealt with, or whether it should be up to Brazil alone.

- Write an imaginary account of the fires from the perspective of an animal living in the rainforest

- Write a poem using the metaphor of the Amazon rainforest being the lungs of the world

- Investigate how much oxygen the Amazon rainforest produces, and how this happens

Fairtrade Fortnight

Fairtrade Foundation has developed a set of resources focusing on something many of us start our mornings with – tea.

They tell the story of how tea growers in Kenya are adapting to a changing climate while improving the sustainability of their farms, thanks to Fairtrade.

Extreme weather events and rising sea levels in the UK

Of course, it’s not just climates with extreme hot and cold weather that are affected by global warming. This activity pack contains two resources based on the theme of the climate change in the UK.

- Impact of the UK on climate change (activity)

- How the UK is linked to the Arctic (info sheet)

Climate science, air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions

Oxfam’s Climate Challenge resources use engaging tools and activities to explore the causes and human impact of climate change.

Investigate the greenhouse effect and analyse carbon footprint data, and use a ‘consequence wheel’, case studies and roleplay to learn about how communities are being affected by climate change.

Teaching teachers about climate change

Lecturer Elena Lengthorn explains why an informed awareness of the realities concerning climate change can and should become a core component of every teacher’s practice…

As a teacher educator, I want to ensure that we give our secondary teachers a grounding in the challenges that today’s children will face from growing up in a declared climate emergency.

The campaign group Teach the Future has produced a set of ten guiding principles that could inform a new National Curriculum. These include:

- drawing links between the ecological crisis and social injustice

- recognition that the concept of ‘sustainability’ can be interpreted differently within the various subjects students study

- encouraging the development of creative and critical thinking skills

- developing a preparedness to confront uncertain futures

A deeper dive

In the meantime, we at the University of Worcester and others are exploring ways of embedding those principles into teaching practice more widely via avenues already available to us. This means we don’t have to wait for major curriculum reforms.

We introduce sustainability on day 2 of our PGCE course. We show our trainees ways of being sustainable themselves while learning with us and after they’ve graduated.

This includes everything from keeping reusable cups to hand for their teas and coffees, through to making shared travel and parking arrangements and using public transport.

In January, after the trainees have completed their first placement and got a general idea of what’s happening in their schools, we’re then able to dedicate time and space for the whole cohort – not just the geography trainees I teach. We engage them with a deeper, more extensive dive into what climate education involves.

Climate-anxious teachers

This year, we invited a group of pupils from one of our local partnership schools, The Chase. They had been trained in the ‘Teach the Teacher’ course run by the charity Students Organising for Sustainability (SOS-UK).

This equips pupils with the skills and knowledge needed to deliver a one-hour lesson on climate change to an audience of teachers. Pupils explain what it’s like to be a young person confronting the climate crisis. They also emphasise the need for climate education.

The school’s formidable sustainability leader, Sarah Dukes, accompanied the pupils, who then shared their perspectives with us.

This was a chance for all of our trainees to hear some key sustainability messages. These ranged from the projected number of future climate migrants, to the size and number of areas at risk from flooding.

More importantly, they were hearing these sustainability messages from children. These pupils were fully aware of the difficulties relating to climate and ecological emergency, and concerned for their futures.

There’s been some recent research around the growing proportion of young people who are climate-anxious. What we perhaps need now are more teachers who are climate-anxious themselves. We need teachers who can channel their awareness and concerns into their classroom practice.

A geographer’s burden

In my own experience, I’ve seen how geography teachers in schools can find themselves becoming the ‘sustainability person’, the ‘eco schools co-ordinator’ or similar.

The DfE’s 2023 ‘Sustainability and Climate Change’ policy paper talked about encouraging all schools to appoint sustainability leads, and providing them with carbon literacy training by 2025. However, it wasn’t a statutory requirement.

I know that anecdotally, some of our graduates have felt empowered to ask questions at their schools about the sustainability policies they have in place, and the forms those should take.

We’re seeing applicants now citing sustainability concerns as among their reasons for wanting to train with us. There’s a growing recognition across all subjects of the need to support our children as they confront the climate and ecological emergency.

Elena Lengthorn is a senior lecturer in teacher education and lead for the PGCE secondary geography course at the University of Worcester. Browse more resources for World Environment Day. Read about how maths plays an important part in teaching climate change.