Racism in schools – Resources, case studies and advice

If you need practical tools and advice on addressing racism in the classroom, we’ve put together a list of helpful resources and strategies…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Looking for effective ways to discuss racism in schools? We’ve curated the most valuable resources and tips to support you.

We also share an inspiring anti-racism case study from STEP Academy Trust and offer insights on how you can reflect on and tackle your own racial biases to create more inclusive classrooms…

How to talk to children about racism

How comfortable are you talking to pupils about race? Here’s how to ensure you embed diversity and inclusion in your classroom, says Burhana Islam…

In a typical non-white household in the UK, the conversation of what it means to be black or Asian, for example, is usually a dinner-time topic from an early age. Systemic racism is an unfortunate fact of life.

The rules and regulations for children of colour are clear. You need to:

- work ten times harder than your white counterparts

- behave ten times better

- keep your head down because, like it or not, you are a representation of a race that doesn’t seem to belong here

Those who believe that primary school children are too young to tackle the subject of racism, arguing that they don’t see colour, are adding to a rhetoric that invalidates the experiences of minority ethnic groups.

By refusing to acknowledge a person’s race, you refuse to acknowledge their identity. You’re refusing to see the layers that have made them the person you see before you.

“By refusing to acknowledge a person’s race, you refuse to acknowledge their identity”

So where do we begin? For a child, teachers are the embodiment of truth. They look towards us for the answers. Before we even open up a discussion about race, we need to understand it ourselves.

- British Red Cross – Talking with children and young people about race and racism

- Anti-Racism Education – Primary resources and secondary resources

- Anna Freud – Podcasts, e-learning and resources about racism

- Premier League Primary Stars – No Room for Racism resources

- Show Racism the Red Card – Education hub

Start with introspection

A part of learning is reflecting. Check your inherent biases by considering the following questions:

- What is race / prejudice / discrimination / systemic racism?

- What does it mean to be white or a person of colour? How do the experiences differ?

- Has anyone ever asked you ‘Where do you come from?’ just because of the colour of your skin? What do these questions suggest about identity, belonging and norm?

Remind yourself regularly: being white doesn’t mean your life is easy. It means the colour of your skin hasn’t made it harder.

Five strategies to try

Considering the above questions won’t make you an expert on race, but it should encourage deeper racial consciousness. This makes it easier to adopt strategies to ensure diversity and inclusion are part and parcel of your classroom climate.

Avoid a tokenistic approach

This is the practice of teaching a text or topic for the sake of identifying (then quickly dismissing) race. For example, do you limit pupils’ study of black people to Black History Month? Or do you embed it in the curriculum beyond October?

Are your classes, sets or houses named after diverse figures such as Mary Seacole or Ghandi, but your curriculum white-washed? Teaching diversity shouldn’t be a box-ticking exercise for Ofsted. Make your intentions meaningful.

Avoid the relentless victim narrative

When you teach about people of colour, do you limit it to refugees, slavery, segregation and bullying? Have you considered incorporating more positive representation?

Instead, use an ‘inspirational leaders’ topic to study notable Muslims who changed the world, for example.

Humanise humanities

When you teach about different religions in RE, do you study each in isolation? Or do you meaningfully interconnect the similarities between the three Abrahamic faiths, emphasising shared experiences instead of magnifying and dwelling on differences?

When you learn about different cultures in geography, do you draw parallels between our lives and theirs? Do you comment on how clothes, school hours and food simply reflect the climate, just like ours do? Or do you use a voyeuristic approach reserved for zoo animals?

When you teach history, do you offer different perspectives of the same event or do you focus on the white saviour narrative?

Do you teach your pupils about slavery, but dismiss Britain’s significant role in the infamous trade? When you tell them about Africa, do you generalise the continent or do you emphasise specific regions for their richness in our history?

Visually represent

Are your classroom displays and books white-washed or do you represent a range of colours and creeds in your classroom so children of colour feel less like the ‘other’ and white children absorb their existence?

Do you limit the texts you study to white authors or do you have empowering main characters of colour to inspire your pupils?

Drop in facts

Are you aware of the cultural impact people of colour have had over the ages? When studying algebra for the first time, tell your students that the word is actually rooted in Arabic, deriving straight from the Islamic Golden Age when algebra was first seriously studied.

Tell pupils that the number zero was actually an Indian invention. It was banned in parts of Europe for hundreds of years because they thought it could potentially hold a secret code.

Burhana Islam is the author of Amazing Muslims Who Changed the World, published by Puffin (RRP £16.99). Find her on X at @burhana92.

Racism in schools – teaching resources

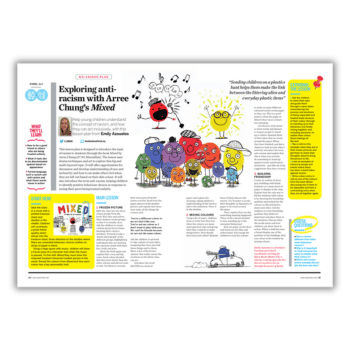

KS1: Exploring anti-racism with a picture book

This free anti-racism KS1 lesson plan introduces the topic of racism to students through the picture book Mixed by Arree Chung. The lesson uses drama techniques and art to explore this big and multi-layered topic.

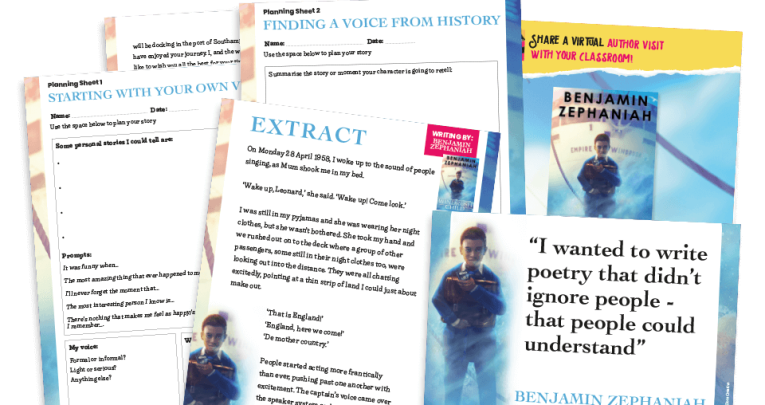

KS2: Windrush Child by Benjamin Zephaniah

Windrush Child by the late, great Benjamin Zephaniah explores themes of identity, belonging and resilience. In the above episode of the Author in your Classroom podcast from literacy resources website Plazoom, Benjamin explained how and why he wrote, discussed the historical truth behind Windrush Child and had some powerful advice for children struggling to find their voice.

Download free accompanying resources, including a PowerPoint, extract, wall display and teacher notes.

Designed to facilitate a deep understanding of the novel over five weeks, this five-lesson resource by Ashley Booth breaks the book into manageable chapter segments for detailed study.

KS3/4: News articles with debate questions

This collection of news articles from the recent past cover racism issues in the UK, USA and beyond. There are KS3/KS4 activities designed for homework or classwork, explanations of difficult words and debate questions. Use them as a complete lesson, a lesson starter or extended learning.

History curriculum audit

Read advice from history teacher Gemma Hargraves about how to make sure your history lessons adopt a much wider, global perspective, then use the free history curriculum audit tool to identify gaps and areas of development at your school.

What schools need to know about systemic racism

Stamping out institutional racism in schools requires more than simply logging the most obvious and egregious ‘racist incident’, explains Peter Radford…

In most schools, racism tends to be treated as a subsection of anti-bullying or behaviour policy. We recognise that it’s a negative behaviour requiring sanction, and that all racist incidents should be logged.

If asked whether they have problems with racism, schools will typically answer no, believing their number of ‘racist incidents’ to be at an acceptably low level. However, this is missing the key point concerning systemic racism. What we must recognise is that:

Incidents of racist bullying and racial discrimination go unreported

At a secondary school I previously worked at, officially, our racist incident count was low. Yet when I surveyed groups from an ethnic minority background in the school, their anonymous responses revealed a shocking picture of daily comments of racist abuse, racist attitudes and social exclusion that they readily admitted were ‘normal’.

Racism and racial harassment take different forms

So-called ‘racist incidents’ don’t account for the myriad ways in which people of colour can be overlooked, ignored or excluded in schools and classrooms daily, due to conscious and unconscious bias.

These aren’t ‘incidents’, since nothing specific actually happened – but that’s the point. Many people of colour and minority ethnic students will miss out on opportunities, feel they have to work twice as hard or live with the fact that they aren’t represented in the curriculum, in leadership, on the school council or similar.

Reacting to racial bullying isn’t enough

When a system is inherently biased in favour of a white privileged majority, any process of change has to be deliberately set in motion. Tackling racism must extend beyond responding, however decisively, to ‘racist incidents’.

“Tackling racism must extend beyond responding, however decisively, to ‘racist incidents’”

Instead, we must educate for change, beginning with an understanding of equity. Equity acknowledges that we are not all equal, and that to treat everyone ‘equally’ makes no sense.

To achieve true equality, we must deliberately treat people un-equally – this is equity. We do this for disadvantaged children in the context of the Pupil Premium. However, we have not, in the main, applied this principle to racial inequality.

Too often, we haven’t proactively sought to address inequalities by changing our systems, curriculums or school structures to promote fairness and celebrate difference.

Peter Radford is a teacher, trainer, coach and inspirational speaker, regularly visiting schools and colleges nationwide. Visit beyondthis.co.uk

Anti-racism case study: STEP Academy Trust

What’s the difference between non-racist and anti-racist schools? It’s all about proactivity, but the process takes time…

It is safe to say that most organisations, schools and trusts claim to embrace diversity and have no tolerance for racism.

STEP Academy Trust was no different. As a trust, we prided ourselves on being open and inclusive. We wanted to improve the life chances of all our pupils, fully in support of anti-racism in schools.

STEP is fortunate to work across several local authorities in two geographical areas. We have always worked closely with and supported the communities we serve.

However, following the tragic events in America with the killing of George Floyd in 2020, we were forced to take a longer look in the mirror.

Was it enough for our trust to simply not be part of the problem, if we weren’t actively contributing to the solution?

This is the core difference between a non-racist and an anti-racist organisation. As a non-racist Trust, our goal was not to perpetuate racism.

“We wanted to hold ourselves to a higher standard; actively eliminating racism”

But now we wanted to hold ourselves to a higher standard; actively eliminating racism and demonstrating to future and current colleagues and our communities what we stood for.

The reason is simple. Taking a position of anti-racism in schools is the best way to improve the life chances of the children, staff and diverse communities that we serve.

Pupils both need and deserve role models who genuinely reflect the diverse world we live in. Our job as leaders is to ask why this is not always the case within the sector.

We need to take action, and challenge our systems, recruitment and development across the education sector.

Anti-racism education

Implementing this kind of culture change across a multi-academy trust requires a strategic approach. There is no one-size-fits-all solution that we can print out and pin up in the corridors.

Every school is shaped by its community, so its anti-racism strategy must respond to that community’s unique culture, beliefs and needs.

As part of a trust-wide anti-racism roadmap, STEP felt it important to have external experts challenge us and give their opinion.

As a result, we engaged an external training provider, Fig Tree International. They reviewed, challenged and thereby improved each academy’s policies and practices within their individual settings.

These are assessed against an extensive framework that enables schools to identify areas for improvement. We could also develop a unique action plan, independently accredited by Fig Tree International, setting out clear steps towards anti-racism.

Anti-racism training

One of the biggest issues to overcome in this process was a lack of staff confidence. This was particularly true for individuals challenging something that doesn’t feel right.

To address this, STEP developed internal and external training for staff and leaders. Modelling scenarios with different layers of racism at play greatly enhanced the learning. It helped staff turn theory into practice and consider how racism manifests in their own schools.

As part of this, academies and the central team appointed ‘local champions’ to guide the action plan. Another key benefit to this training was to establish a shared language for discussing racism and discrimination.

Ongoing CPD and support for staff has given them the confidence they need to reflect and discuss anti-racism confidently.

Building community understanding and engagement with the Trust’s anti-racism policy was another challenge.

This is a long-term endeavour, even more so than building understanding within the school. This is because it depends more heavily on their willingness to engage.

School leaders focused on communicating with parents through formal workshops and informal conversations, along with regular newsletters reporting back on the school’s progress.

This, combined with the eager reports of pupils sharing the day’s learnings at home, has built a wider understanding of the Trust’s anti-racism policy and why we’re pursuing it.

Barriers to anti-racism in schools

Time itself felt like the biggest barrier of all. But we needed to give everyone time to understand the direction, take part in training and to hold up that mirror to our own behaviours and actions.

As with any key priority for our trust, it is essential that staff have adequate time, training and support.

Our work in this area should never be seen as a quick fix but an ongoing process; empowering brave members of our own staff to share stories of experiencing racism, along with hearing from guest speakers who helped the school community understand the need for change, has been central to this.

How we review progress

Every successful strategy requires clear measures of success. When it comes to culture change, progress can feel nebulous at best. External accreditation and review is extremely helpful in this regard, providing an independent assessment with great expertise.

However, STEP has also introduced a range of internal measures to help leaders monitor and improve progress.

Impact monitoring

First, each academy’s anti-racism objectives are built into its yearly plan for ongoing review and impact monitoring. Schools also review progress at every executive team meeting.

“Every successful strategy requires clear measures of success”

Informal training

Second, ongoing informal training is offered to all staff. Equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) training for leaders and trustees will focus on reviewing perceptions and help to shape further directions and actions across each academy.

Surveys

Annual pupil surveys at each academy now also include key questions around pupils’ understanding of anti-racism.

They also include questions on how they perceive the importance of anti-racism in their school. This allows us to gauge the impact of policies and attitude changes over time.

Conversations

But there’s nothing quite like simply talking to our pupils and our community. Leaders engage pupils in conversations about their understanding of anti-racism and its place in the curriculum.

Many of STEP’s academies have specific curriculums built as part of their PSHCE courses to delve deeper into the issues.

This also presents valuable opportunities for pupils to share their views and build their understanding through Philosophy for Children lessons.

Whilst we have made much progress though our roadmap, action plans and training, there is still a lot to do. It is tempting to chase ‘quick wins’ with any policy, but this is ultimately not our goal.

What we’re doing now is, rather, the beginning a long-term re-establishing of culture and priorities, which must permeate our entire organisation.

Embedding anti-racism in schools

The individual anti-racism action plans developed by academies within STEP Academy Trust are tailored to their unique needs.

However, we also adopted Trust-wide policies to foster understanding and appreciation for diversity among staff and pupils alike.

These include policy and recruitment changes aimed at building a leadership that reflects the diversity of our communities.

- Each part of the organisation has a Race Champion, leading training, thinking, support and reading in each setting – whilst helping to shape the trust-wide plans each year through the trust’s Anti-Racism Network meetings.

- We’ve developed a leadership behaviours framework to create a positive culture, led from the top.

- We have updated school meal menus to reflect the diversity and cultures of cuisine within each of our academies and trust.

- We have amended all policies to reflect diversity statements and practices.

- Schools have reviewed and updated recruitment processes, including the introduction of blind recruitment, where the shortlister removes all names and protected characteristics.

- We’ve amended career pathways to increase transparency and include a rich variety of ongoing training and development opportunities.

- We have an ongoing process of de-colonisation of the curriculum, alongside a full review of texts used within reading, to introduce a broader range of voices and influences.

These policies lay the groundwork for change.

Planned future activities include specific targeted training and development for our future leaders, reviewing how well our websites and communications reflect our stance, and developing a non-negotiable resource bank that all pupils should have access to.

Paul Glover is CEO at STEP Academy Trust. Follow the Trust on X at @thesteptrust

Tackling teachers’ racial bias

Gordon Cairns examines the extent to which unconscious racial bias may be affecting students and teachers across the education system…

The taint of racism can infect all areas of British life, whether consciously or unconsciously. Even the supposedly liberal profession of teaching isn’t immune.

According to a study published earlier in 2020, levels of subconscious racial bias exhibited by teachers are comparable to to any other sector of society, with three out of four teachers demonstrating implicit bias – just 0.1% less than wider society.

Acting on biases

However, Dr Lasana Harris – senior lecturer in social cognition and experimental psychology at University College London – isn’t surprised that members of an ostensibly liberal profession should display unconscious racial bias. He explains that prejudice is a response, learned from the society in which we live:

“Your profession doesn’t make you exempt. Racism isn’t based on your values, although that flies in the face of how people think about it. If you live in a racist society, you too will be racist. That is not a choice.”

“If you live in a racist society, you too will be racist. That is not a choice”

That said, we do have a choice in how we act on those biases: “Teachers who notice these biases are more willing to regulate them.”

‘Normalised’ racial bias

Professor Tracey A Benson, co-author of the book Unconscious Bias in Schools, goes further, asserting that racial prejudice is so common throughout the education sector that it would be more accurate to call it ‘normalised’ racial bias, rather than ‘unconscious’.

A former school principal, he thinks it ‘insane’ that educators view the poorer academic performance of Black students as typical behaviour.

“In the everyday work in the classroom, in the school building and in school policy – even in the way that we interact with our students – racial bias is at play all the time,” he says.

“We don’t even see the anomaly that we have an achievement gap based on skin colour. It is so normalised that we just accept it to be so.

“It’s not ‘unconscious’, it’s normalised. Unless we draw attention to it, we don’t realise it’s not normal.”

Professor Benson teaches aspiring school principals at the University of North Carolina, USA. For the past five years, he has asked his students on placement to record how often students of a different race interact with their teacher, how many are positively praised, and how many are corrected.

“Unless we draw attention to it, we don’t realise it’s not normal”

Describing the results to date, he says “99% found that white students:

- are redirected less often

- interact with the teacher more often

- receive preferential treatment in terms of the rules

“For example, if there’s a rule that students have to raise their hands to get up, it’s more often that students of colour would be held to that strict standard, whereas white students would have privilege. And that’s how unconscious racial bias takes place unconsciously in the classroom.”

Higher expectations

Benson goes on to cite an experiment which found that teachers would typically mark a white student’s answer paper more harshly than when given the same answer paper from either a Black or Latino student:

“What that study tells us is that teachers have higher expectations of white students. They are more critical of them and expect them to do better. However, they think this is the best that Black and brown students can do, so give them a higher grade and more positive comments.”

“What that study tells us is that teachers have higher expectations of white students”

While the obvious effects of racial bias on students’ post-school career might include lower academic attainment, Benson adds that it can also give rise to a number of other negative psychological outcomes affecting self-esteem.

“People of colour end up believing ‘We are less intelligent’ and can develop imposter syndrome. Though you might be highly successful, you have this internal fear that you’re not good enough, and this harms your psyche.

“You have this internal fear that you’re not good enough”

“When you’re put in a highly stressful situation, your blood pressure goes up. The nervousness caused by imposter syndrome can result in health implications for people who have been on the receiving end of intensive and persistent racism. The list of racism’s negative effects is very long.”

Reducing unconscious bias in schools

One approach to reducing unconscious racial bias in schools could be to positively discriminate when employing teachers in favour of ethnic minority candidates. This is an approach previously endorsed in 2015 by Ofsted’s then chief inspector, Sir Michael Wilshaw.

Current statistics paint a compelling picture. Over 90% of teachers nationwide are white, while one third of students are not.

Professor Benson supports taking such an approach, though warns that even Black teachers – himself included – can be guilty of unconscious racial bias.

“Over 90% of teachers nationwide are white, while one third of students are not”

“I think we have to be deliberate, and offer an equal and opposite response, if we’re to continue to undo all the harm we’ve done.”

Tackling prejudice

He goes on to add that positive recruitment won’t be enough, however. We should also employ additional methods of tackling prejudice, including blind grading and blind referrals – two strategies known to work, though not, as yet, widely used.

Above all, he stresses that more needs to be done than simply ‘being aware’ of unconscious racial bias: “School principals just think conscious awareness-raising is enough. They think that if they think better and know better, they will do better, but that’s not the case. We have to search out a strategy to interrupt the bias.

“We need to develop the ability to talk about it; to say there are people of different colours, that there is racism, and that this is what it looks like.

“We need to develop that capacity. The reason we find it so hard to talk about racism is that we spend the majority of our lives being told it’s bad to talk about racism.”

“We have to search out a strategy to interrupt the bias”

Once we’re able to get our own staff and leadership comfortable in talking about race and racism, it’ll be necessary to identify those areas where there are gaps in student achievement, suspension rates, participation rates and wherever other gaps might exist.

If we fail to pay attention, unconscious racial bias will continue to leave a wide-ranging, negative impact in our schools and classrooms. Having developed a means of measuring that impact, it’s then up to us to formulate effective strategies for mitigating it.

Gordon Cairns is an English and forest school teacher who works in a unit for secondary pupils with ASD; he also writes about education, society, cycling and football for a number of publications.