Black History Month activities – Best 2025 resources for KS2 / KS3

Celebrate Black History Month in October with these lessons, assemblies, recommended movies and more…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Browse this list of recommended Black History Month activities to find the perfect way to cover this important event in your classroom this year…

Table of contents

When is Black History Month?

Black History Month takes place in October in the UK.

What is Black History Month?

In the UK, Black History Month is a national celebration that aims to promote and celebrate the contributions Black people have made to society. It’s also an opportunity to promote an understanding of Black history more widely.

Black History Month theme 2025

The theme for 2025 is ‘Standing Firm in Power and Pride’, highlighting the profound contributions made by the Black people who have shaped history, while also looking towards a future of continued empowerment, unity and growth.

Why is teaching Black British history important?

Natalie Russell, head of delivery and development at social enterprise The Black Curriculum, says, “Students across the UK are not being taught Black British history consistently as part of the national curriculum in a committed manner. This is despite numerous findings demonstrating its importance.

“When young people are not taught their history within Britain, their sense of identity, belonging and self-esteem is negatively impacted and social relations hindered.

“Self-esteem is directly linked to the associations you make with who you are and the world around you. The curriculum creates a picture in a child’s head as to how the world works. It gives them the skills and tools they need to operate in that world.

“In failing to teach students about Black British history, we are failing to teach British history accurately. We’re also failing to provide an empowering learning experience for every student.”

Black History Month activities and resources

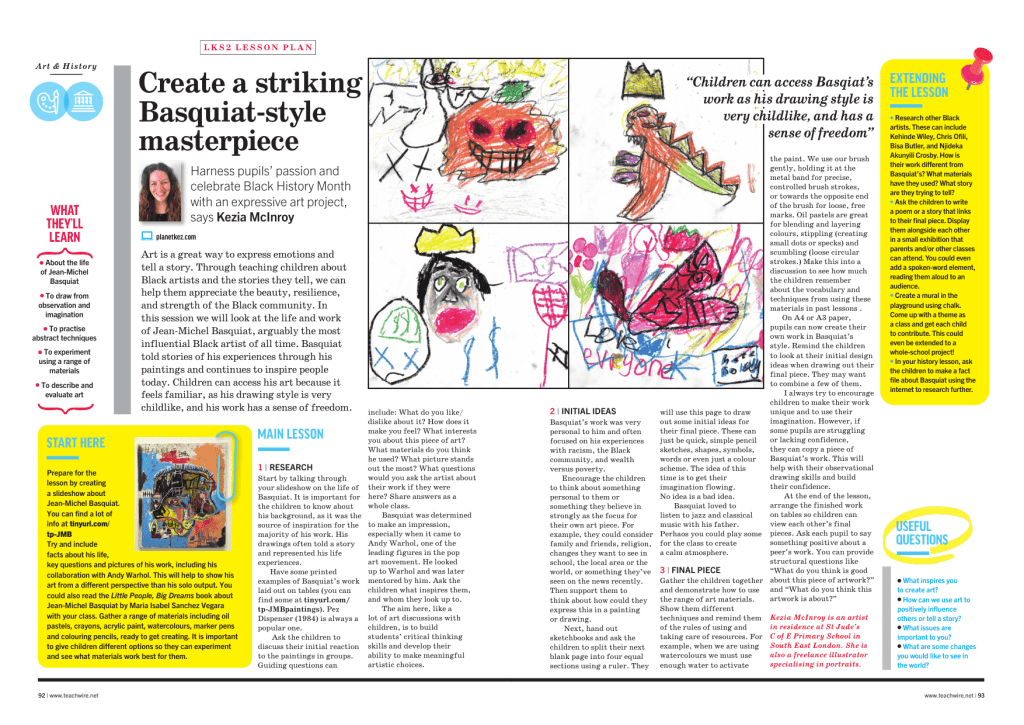

Black History Month art lesson plan

Use this KS2 art lesson to look at the life and work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, arguably the most influential Black artist of all time. Basquiat gained recognition as part of the New York graffiti duo SAMO and went on to receive critical acclaim.

Children will enjoy accessing his art because it feels familiar – his drawing style is very childlike, and his work has a sense of freedom.

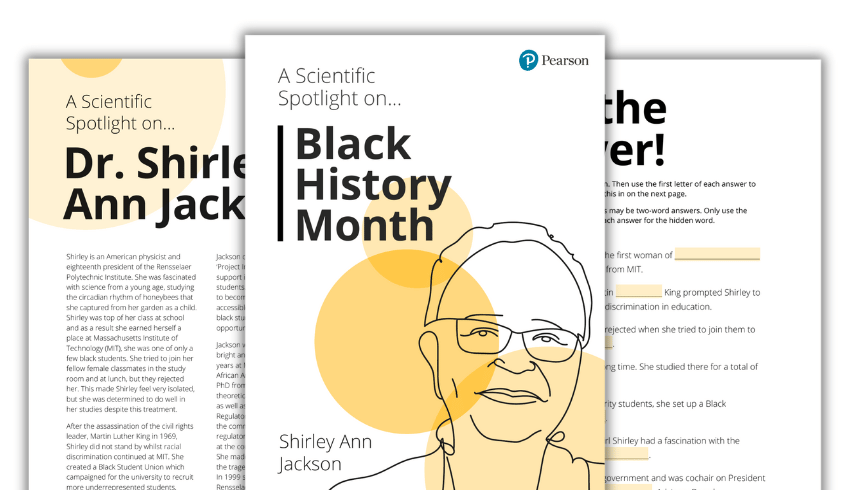

Discover black scientist Dr Shirley Ann Jackson

Use this free activity booklet from Pearson to explore key facts about famous Black scientist, Dr Shirley Ann Jackson. There are also fun activities and discussion starters for your students.

Windrush Child resources

Podcast and accompanying resources

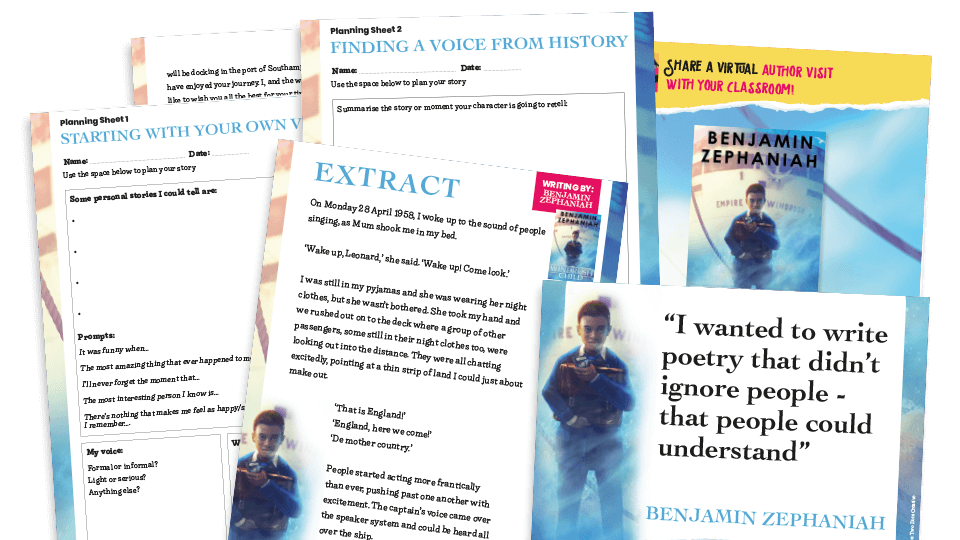

Windrush Child by the late, great Benjamin Zephaniah explores themes of identity, belonging and resilience. It’s part of the Scholastic Voices series which aims to highlight underrepresented histories through personal and powerful narratives.

In the above episode of the Author in your Classroom podcast from literacy resources website Plazoom, Benjamin explained how and why he wrote the book, discussed the historical truth behind Windrush Child and had some powerful advice for children struggling to find their voice.

Download free accompanying resources, including a PowerPoint, extract, wall display and teacher notes.

Stand-alone lesson on making predictions

This stand-alone lesson plan is the first part of Literacy Tree’s Windrush Child Writing Root – a 15-session sequence leading to thought-provoking writing outcomes.

For this first lesson you only need access to the front cover and prologue of Windrush Child. The lesson focuses on making predictions about a text.

Five-week reading resource

Designed to facilitate a deep understanding of the novel over five weeks, this five-lesson resource by Ashley Booth breaks the book into manageable chapter segments for detailed study.

British Empire and slavery case studies

The case studies included in this free download from 40 Ways to Diversify the History Curriculum by Elena Stevens all emphasise the role and agency of enslaved people in bringing about abolition.

Use the case studies and lesson enquiry ideas in secondary history lessons about the British Empire and slavery. The case studies cover the following people:

- Sarah Baartman

- Dido Elizabeth Belle

- Portchester Prisoners

- Mary Slessor

- The Three Kings of Bechuanaland

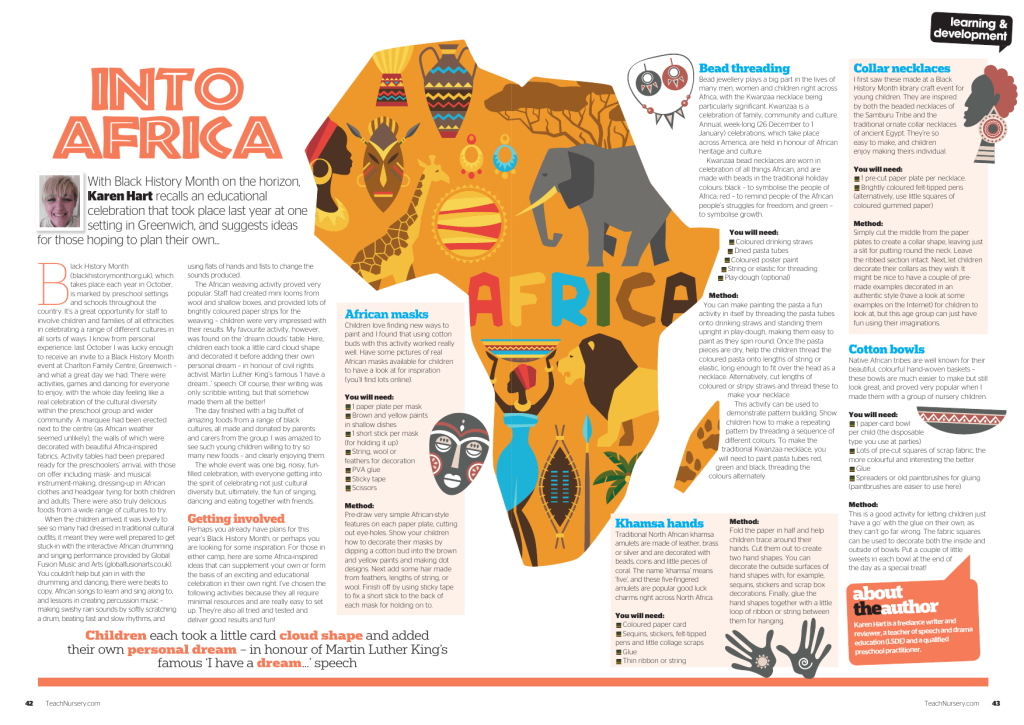

EYFs craft activities

In this free Black History Month EYFS download you’ll find five Africa-inspired ideas that can supplement your own plans or form the basis of an exciting and educational celebration in their own right.

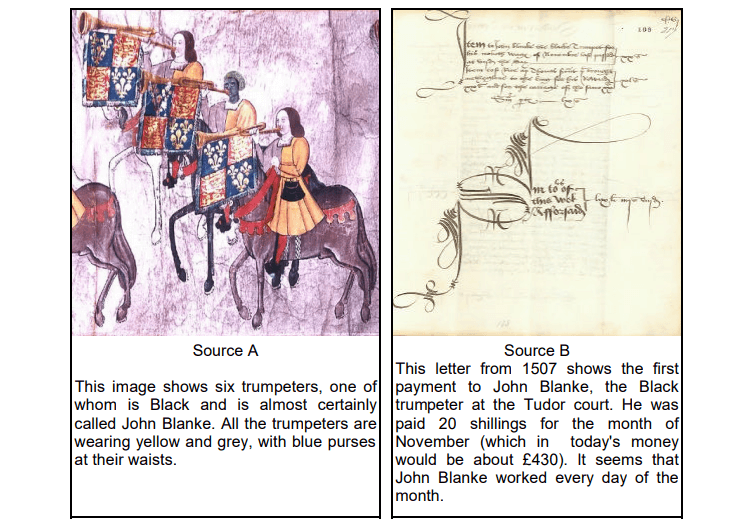

Black British History lesson plan

It’s not always easy to find Black History Month activities that help children learn about Black British history.

Patrice Lawrence’s novel Diver’s Daughter offers a valuable opportunity to help pupils discover more about the diversity of the people who lived in England during the Tudor times.

By exploring the experiences of characters whose stories are not always told, and contrasting them with their own rights and freedoms, this Black History Month KS2 lesson plan for schools enables children to develop empathy alongside their historical knowledge and understanding.

Inspirational people comprehension and writing activities packs

Teach LKS2 students about influential footballer, Marcus Rashford. This Black History Month activities pack from Plazoom introduces Marcus and explains how he’s using his influence to campaign for political change.

It contains text and comprehension questions, a PowerPoint, discussion cards and a writing task sheet. There are similar packs for KS1 (Rosa Parks) and UKS2 (Barack Obama).

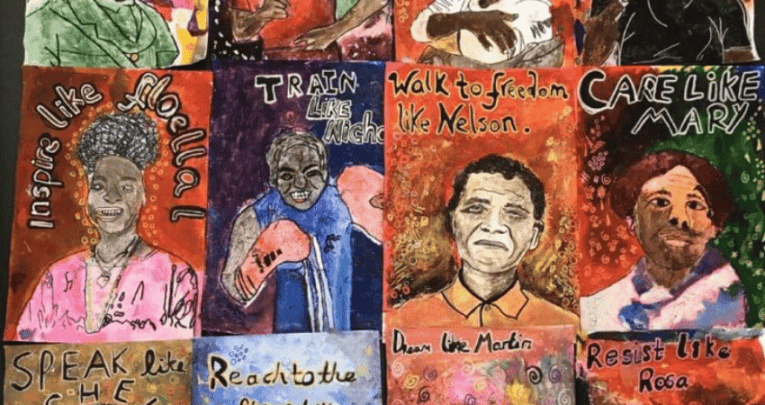

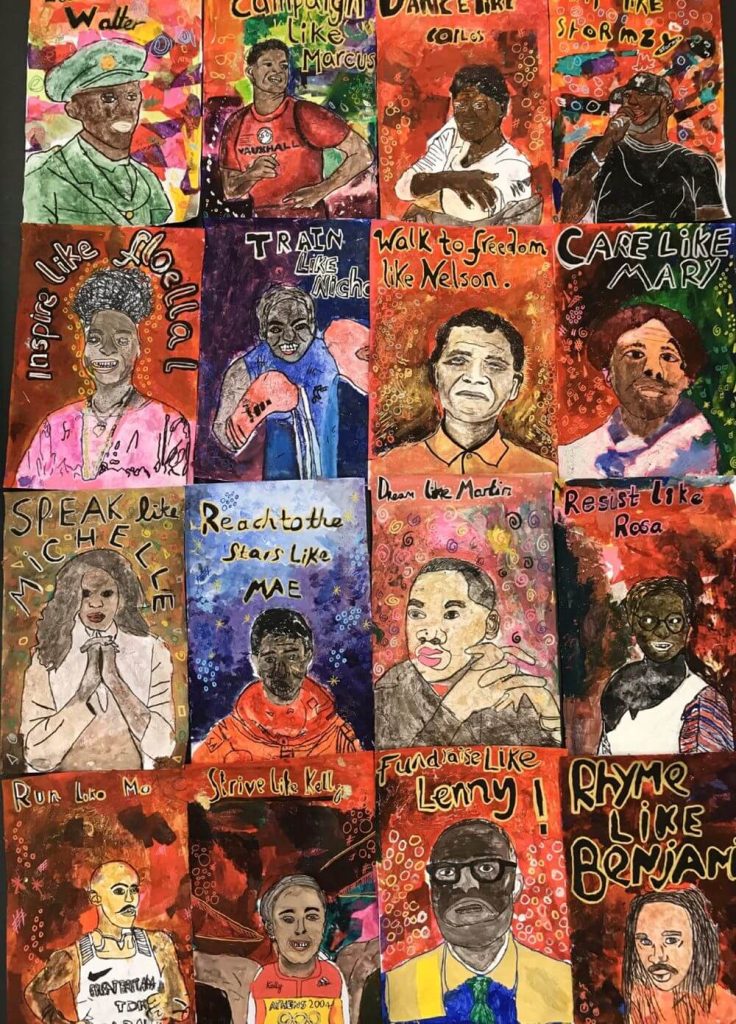

Inspirational posters art activity

This KS2 art idea involves children working together to produce inspirational portraits of significant people. The posters make an inspiring display when placed together.

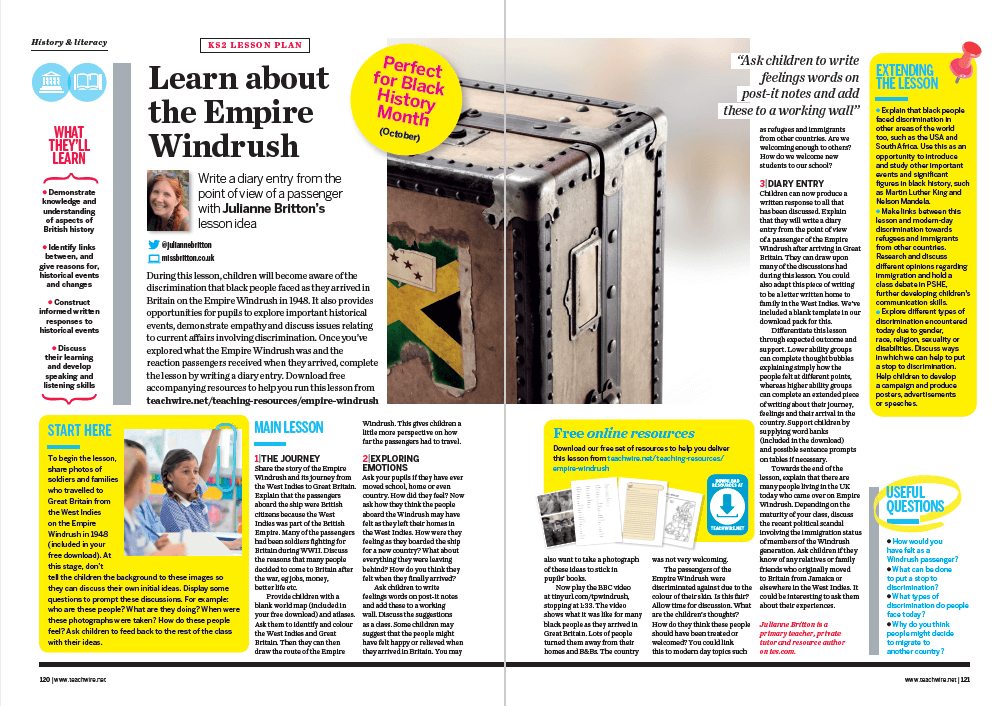

Empire Windrush lesson plan

During this KS2 Black history lesson, children will become aware of the discrimination that Black people faced as they arrived in Britain on the Empire Windrush in 1948.

It also provides opportunities for pupils to explore important historical events, demonstrate empathy and discuss issues relating to current affairs involving discrimination.

Once you’ve explored what the Empire Windrush was and the reaction passengers received when they arrived, complete the lesson by writing a diary entry.

The lesson plan and all accompanying resources are included in this download.

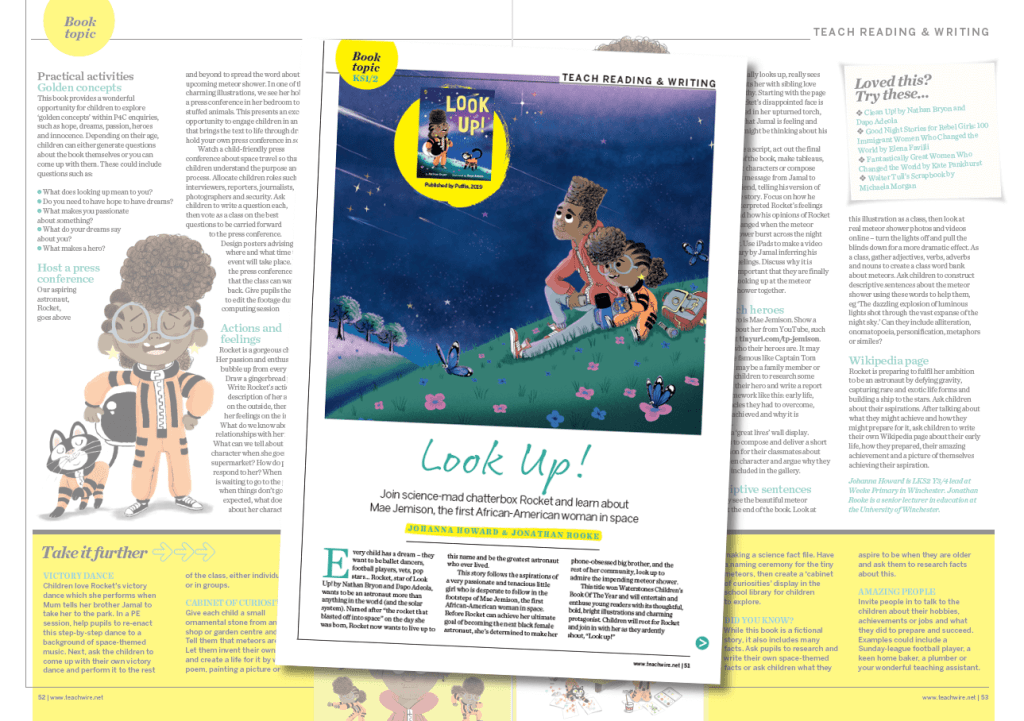

Books for topics – Look Up!

Join science-mad chatterbox Rocket and learn about Mae Jemison, the first African-American woman in space, with these cross-curricular KS1/2 Black history activities based on the picturebook book Look Up! by Nathan Bryon and Dapo Adeola.

This story follows the aspirations of a very passionate and tenacious little girl who is desperate to follow in the footsteps of Jemison.

Floella Benjamin drama lesson

When planning your Black History Month activities, there are many people whose struggles, achievements and inspirational stories could be shared with our children.

Floella Benjamin is certainly inspirational, but has the added advantage of having recorded her experiences in a beautifully written and accessible book, Coming to England.

This KS2 Black history drama lesson plan uses drama to explore some of Floella’s experiences, while giving the children the opportunity to discuss and express their views on discrimination, inequality and injustice.

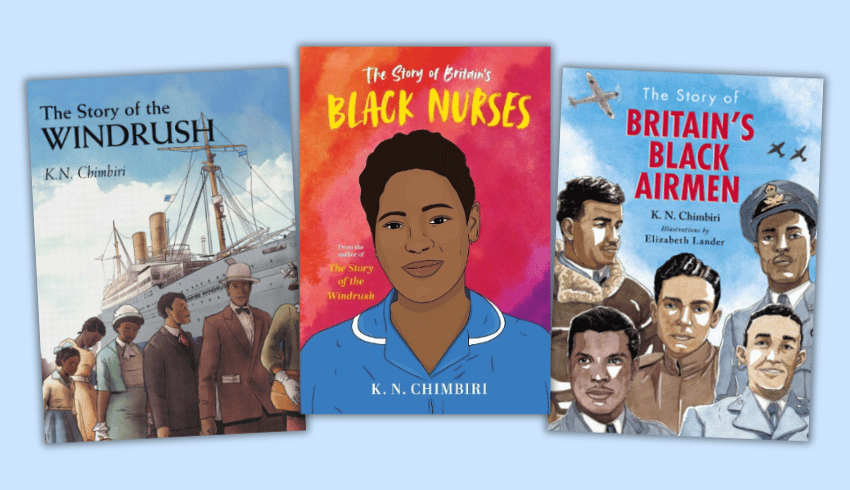

Black British history books

Author K. N. Chimbiri writes and speaks about Black History, and offers virtual school visits and history-themed workshops for children. Her latest title, The Story of Britain’s Black Nurses, is book 4 in the Our Story: New Black Histories series.

Sarah Forbes Bonetta KS1 lesson plan

Sarah Forbes Bonetta was one of Queen Victoria’s goddaughters, but unlike the others, she was also an African princess. Born in 1843, she was captured, aged four, and given to Queen Victoria as a ‘gift’.

This KS1 history lesson plan by Alf Wilkinson looks at whether Sarah was a ‘significant figure’ of the Victorian era.

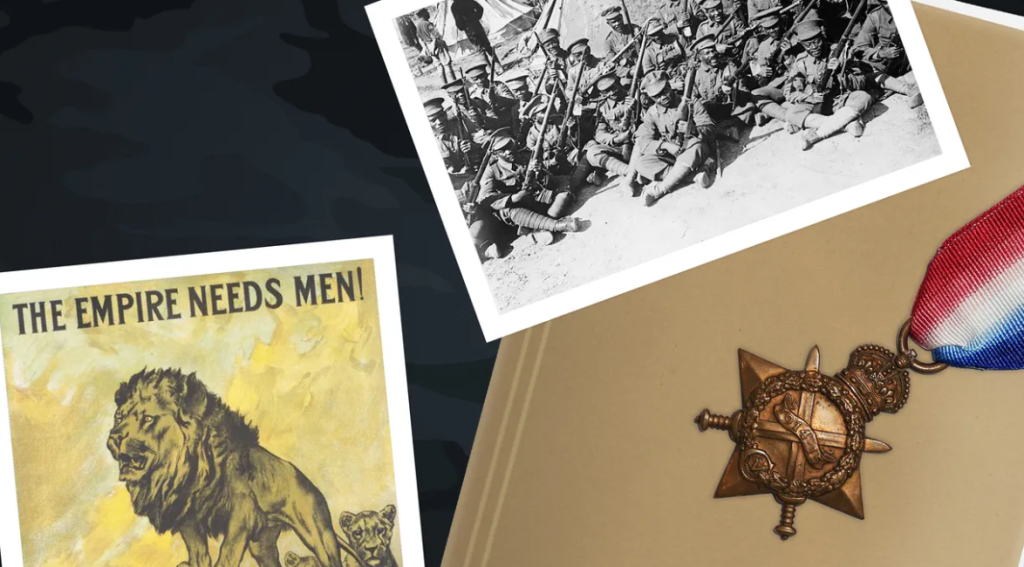

British Army resources

The British Army Supporting Education team has developed free modern educational resources intended to help teachers explore how Black history has shaped the British Armed Forces. The PSHE, wellbeing and citizenship-linked resources are aimed at KS3/4 and contain materials for organising a themed lesson, with an accompanying assembly.

The resources seek to explore the stories of Black British, African and Caribbean service personnel, highlighting the contributions made by Black Army personnel throughout history – including shedding light on the significant, yet underreported roles of Black women.

British Red Cross resources

Use this activity with secondary school students to discover some exceptional Black British humanitarians. Learners will:

- Discover the work of Black humanitarians on British society

- Reflect on assumptions about people and challenge stereotypes

- Think about the resilience and kindness of people

- Celebrate people’s stories and achievements

- Reflect on the qualities of a humanitarian

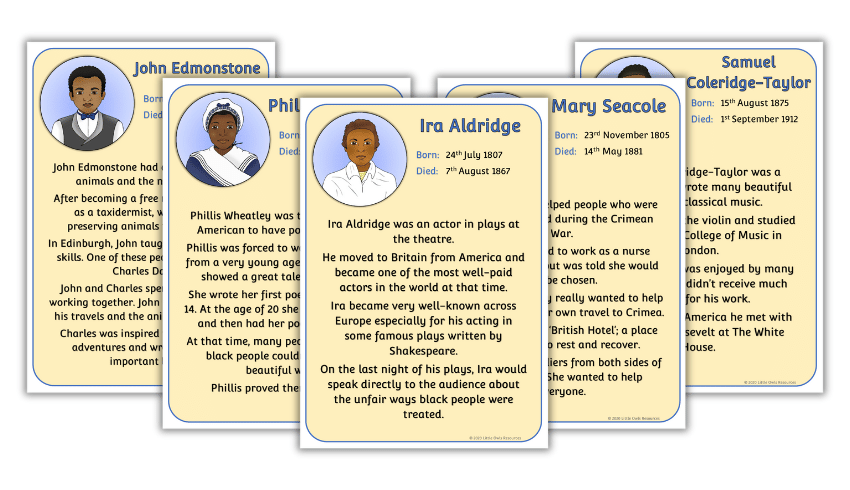

Little Owls resources

Little Owls Resources has a wide range of free UK Black History Month resources, including A4 information sheets, cards, mats, word cards and biographical writing worksheets.

The importance of Black History Month assembly

This Black History assembly from TrueTube is designed to celebrate (and discuss) the event. You can download the assembly plan which includes links to include related videos.

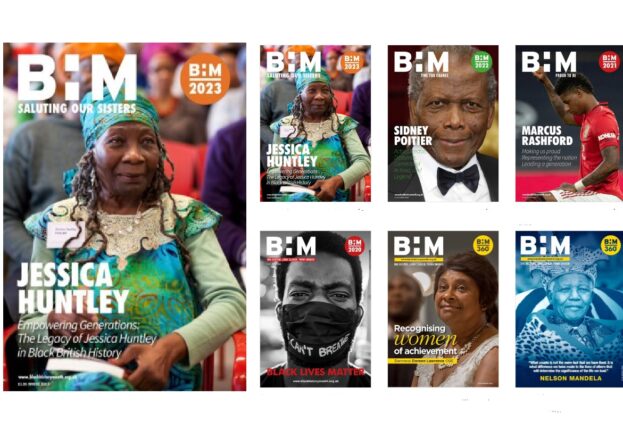

Black History Month magazine

The 2025 edition of Black History Month Magazine will feature a wide range of writers, from sportspeople and entertainers to educators and businesspeople, all talking about how to elevate Black people and be an ally.

Find out how you can get this year’s edition and read older editions.

Empire Windrush education resources

These two massive Empire Windrush education resources, published by Windrush Foundation, include more than 200 pages of information, activities, photographs and data for students, teachers, parents, guardians and anyone keen to know some of the interesting post-war stories of Caribbean people in the UK.

Into Film recommended movies

As per usual, Into Film has you covered with topic-related films and accompanying teaching resources.

This list ranges from films like The Princess and the Frog for young students to the seminal To Kill a Mockingbird and the harrowing 12 Years a Slave.

Many come with film guides for teachers or related resources to help teach children in your classroom.

Influential Black Britons illustrated book

This resource from UK Parliament contains stories of influential Black Britons who have impacted UK laws and equal rights. Use it to embed stories of important Black Britons across your KS1 and KS2 curriculum.

Black history timeline of resources

At Black History 4 Schools you’ll find a whole list of links to useful resources all separated into historic sections:

- Black presence in Tudor times

- Transatlantic Slave Trade and Abolition of slavery

- Black presence in the 18th, 19th and 20th century

- Black presence in the 20th century

- South Africa

Black British history lessons with Professor David Olusoga

With only 8% of people reporting ever learning about the colonisation of Africa in schools, resource website iChild has partnered with Professor David Olusoga and his sister Dr Yinka Olusoga to create resources focused on Black history as an integral part of British history, not an add-on.

It’s part of the Captivating Classrooms collection, which features more than 250 digital resource units. The resources include editable PowerPoints, teacher notes, worksheets, keyword flashcards, posters and certificates. Find out more about subscribing.

Read more about David Olusoga’s schooldays and the racism he endured.

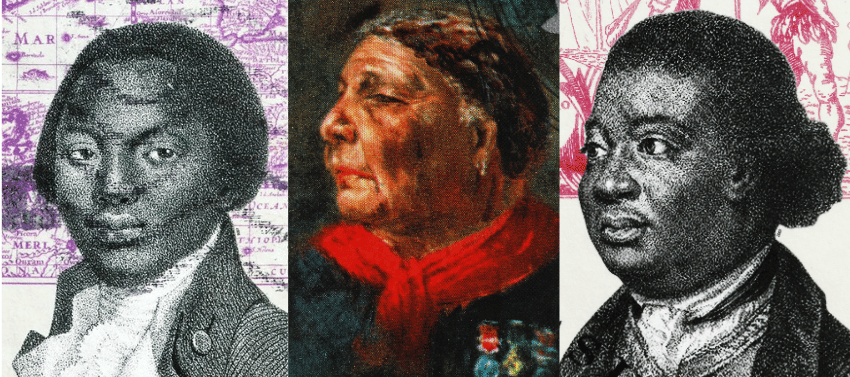

Inspiring Black British people to study

The stories, struggles, and triumphs of Black Britons are woven deeply into the fabric of this nation, from its colonial past to its multicultural present.

Here, teacher Naila Missous highlights figures whose legacies have shaped our shores and whom children in Britain should know about…

- Olaudah Equiano – Author whose compelling autobiography helped turn the tide against slavery

- Claudia Jones – Political activist and founder of the Notting Hill Carnival, who championed both civil rights and Caribbean culture in Britain

- Mary Seacole – British-Jamaican nurse who cared for soldiers during the Crimean War, often taught alongside or in contrast to Florence Nightingale

- Windrush generation – Those who journeyed from the Caribbean to rebuild post-war Britain, only to be met with hostility, systemic racism and (more recently) scandalous deportations

- Diane Abbott – The first Black woman elected to Parliament, whose political career has paved the way for others while often exposing the deeply ingrained racism of British political life

- Ignatius Sancho – Writer, composer and abolitionist who was the first known Black Briton to vote in a parliamentary election

- Walter Tull – One of the first Black British professional footballers and an officer in the First World War

- Baroness Floella Benjamin – A familiar face to generations of children from her time on children’s television, who helped bring discussions about representation, diversity and the Windrush generation into modern, relatable contexts

- Grace Nichols – Poet whose lyrical writing introduces young readers to themes of identity, culture and belonging

- Chris Ofili – Black artist who uses colour, symbolism and storytelling

Naila Missous is a teacher and leader of humanities and RE. She is the author of Bloomsbury Curriculum Basics: Teaching Primary RE (£20, Bloomsbury).

How to avoid the ‘siloing’ effect of Black History Month

I want to be honest and open with all who read this. I spent years getting diversity and inclusion wrong.

As a teacher and curriculum leader, I was certain that because I featured the lives of Black people, women and other under-represented groups in my curriculum via dedicated lessons, assemblies, tutor time posts or even homework, I was getting it right.

However, I now know that I was being naïve. I’d fallen into the same narrative traps that have ensnared many others. I write these words having since educated myself, researched widely and spoken to a number of Black educators, including Emily Foloronshu (@MissFolorunsho) and Thandi Banda (@STEMyBanda), who were gracious enough to assist with the writing of this article.

Deeper thinking

Black History Month (BHM) is a well-intentioned celebration of the invaluable contribution made by Black peoples from the African Diaspora to British society. To be clear, I’m not going to argue here that we should scrap BHM. Indeed, it must be made an integral part of the school year.

I am, however, keen to explore the need for us to think more deeply about the time we allocate in the history curriculum to studying the contributions and developments made by Black people.

With big, one-off events such as BHM in place, do we risk treating the contribution of Black people as merely an add-on, for one month only?

Are BHM and other similar events just tokenistic attempts at inclusivity? Should we instead be looking to seamlessly connect the perspectives of broader, more inclusive groups, in order to arrive at a more thorough understanding of life in the past?

“Do we risk treating the contribution of Black people as merely an add-on, for one month only?”

Where we are

In recent years, some schools have adopted a more diverse and inclusive curriculum in which they connect the contributions and developments of Black people to the perspectives and contributions of non-Black people. But, at least in my experience, this is far from the norm.

In primary schools, Black History Month will typically involve a themed assembly and a month of topic-related activities. These may celebrate the contributions of individuals like Martin Luther King or Jesse Owens.

This is a start, but does it really show that we value the contributions made by Black people to the country and world we live in today? To what extent does such activity meaningfully help students understand cultural diversity?

In secondary schools, BHM tends be delivered through assemblies, workshops and PSHE lessons. But again, it’s activity that’s limited to one month. It’s often not linked to any other current learning, resulting in its purpose being lost amongst students.

Surely we can do better than this?

The power of history teachers

We history teachers have a superpower – a knowledge of the past that enables us to shape the minds and perspectives of all the children who pass through our classrooms.

I often think about the hundreds of students who have left school knowing that ‘Hitler invaded Poland in 1939’ or that ‘William the conqueror used castles as a form of social control’ because I told them so.

We create a legacy of knowledge in our classrooms. The perspectives and viewpoints we consider in our lessons will live on in the minds of the next generation, and possibly the generation after that.

So it follows that we have an enormous responsibility to ensure that what we teach is as well thought out, representative and accurate as it can be.

So, with that in mind, how many of our students could name a Black inventor? How many could name a Black man or women who has led social change in the UK? Very few, would be my guess.

And yet, history is full of Black people who contributed to the development of the world we currently live in. Yes, Martin Luther King was a globally important figure within the Civil Rights Movement. But don’t children in the UK deserve to also learn about more relatable individuals who have contributed in some way to the development of the country they know today?

This issue extends beyond the history curriculum. Every subject area, across all Key Stages, can do more to value and celebrate the contributions of Black people. If we don’t, we perpetuate the narrative that non-Black individuals almost exclusively shape and tell history.

Rethinking curriculum design

While there has been some progress in ensuring history curriculums reflect wider perspectives, we must do more.

Consider how most schools will examine women’s fight for universal suffrage in one unit, and then the experiences and struggles of Black people during the height of the slave trade in another. I would argue that by isolating such topics, we present the groups concerned in a very particular way.

Instead, let’s look at how we can design our curriculums so they reflect the perspectives of said groups within all topics. In place of standalone lessons, let’s encourage a more organic reflection of different groups at each curriculum stage. At the same time, we shouldn’t give our students the impression that Black people ‘began’ as slaves. Instead, we should look more widely at African kingdoms, and the roots of humanity in Africa.

The amazing work of Katie Amery and Teni Gogo in this area is worthy of high praise. Earlier this year they authored a textbook for Oxford University Press, titled KS3 History Depth Study: African Kingdoms – West Africa Student Book, which reshapes the curriculum work schools have previously done on African heritage.

It prioritises the responsibility we have as teachers to maintain a legacy of knowledge that challenges racism and preconceived stereotypes around Black people.

The standalone problem

Looking back, I now shudder to think of those lessons, homework assignments and other tasks I planned and delivered to ensure I’d essentially ‘ticked the inclusion’ box. Because whatever it was, it certainly wasn’t an inclusive curriculum.

The fact that we were having to even consider how to ‘add’ the perspectives of different groups into our topics illustrates just how naïve we’ve been in this area.

We should carefully weave and sequence such perspectives throughout curriculum content. As history teachers, we should considering more widely those sources and interpretations that might help to broaden the knowledge base.

“Looking back, I now shudder to think of those lessons, homework assignments and other tasks I planned and delivered”

For example, you can easily use diary entities and letters from Black soldiers serving in WWI regarding their experiences of the trenches alongside sources from white soldiers.

Alternatively, when covering the recruitment of soldiers in WWI, we could cast our topic net more widely by directly comparing recruitment drives on the home front with those pursued across the wider Commonwealth.

Pertinent and explicit

When I started researching this topic, I was shocked to find that some schools don’t celebrate BHM at all, but celebrate it we must.

In Emily Foloronshu’s view, BHM can be made both pertinent and explicit by going beyond just the US Civil Rights Movement. It’s about thinking more deeply about how the event links to Black people’s lives in the UK.

Above all, collaborate and connect with other educators and academics. Because there’s so much good work being done nationwide to ensure we all reflect on our responsibilities, as history teachers, to devise an inclusive curriculum that accurately and consistently reflects the perspectives of different communities.

Lindsay Galbraith is assistant vice principal – teaching, learning and curriculum at a school in Telford; follow her at @MsGHist

What to do next

- Spark debate among your teams. Is your curriculum inclusive, in terms of there being seamless connections between the experiences of wider communities and your current perspectives?

- Reflect on whether your curriculum feeds into stereotypical ideas about Black people. Are you only teaching the history of Black people from the slave trade and beyond?

- Read widely. A great place to start would be Emily Folorunsho’s chapter in the What is History Teaching, Now? handbook edited by Alex Fairlamb and Rachel Ball

- Recruit a team of teachers and students to help you with your planning for Black History Month

- Consider cross-curricular links beyond the history curriculum and spark debate across your school