Curriculum sequencing – How cognitive science and careful planning boost learning

Learn how to structure and sequence teaching units in a way that is most beneficial to children’s learning…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Ensure your students build on prior learning and deepen their understanding by making sure your curriculum sequencing makes sense…

How to decide what to teach and when

If a curriculum is to be coherent and follow a logical progression, we need to pay attention to the order in which we introduce and revisit knowledge, in whatever form that might take, say Kat Howard and Claire Hill…

What is curriculum sequencing?

The curriculum in many subjects is dependent on a deliberate approach to the sequencing of knowledge. This is because one concept often relies on the understanding of what has come previously and what will come next.

Effective sequencing can also provide a way of embellishing and unifying what may otherwise seem like disconnected fragments of knowledge. To create a sense of coherence for the discipline that we teach, we need to ask ourselves:

- Why this?

- Why now?

Cognitive load theory informs curriculum sequencing by revealing the role of memory in helping students build the cognitive architecture required to access the curriculum effectively.

Curriculum sequencing as a narrative

Sequencing of the curriculum is clearly more than the ordering of its component parts. It’s about the relationships and connections between them, and the deeper understanding that the sequence allows our students to access.

It is more than simply ‘this follows this, follows this’. Instead, it’s a narrative. It tells the story of our subject and is a conversation between its parts.

However, curriculum design can sometimes be reduced to ‘Fragments of knowledge [that] float around without being placed in a coherent structure’, as noted by Mary Myatt in her book Building Curriculum.

“When sequencing learning we need to judiciously select the knowledge most likely to support and connect to new learning”

Or, in some cases, it’s disjointed units of work merely connected by the command words of GCSE exam papers, with no real sense of cohesion.

We begin to move towards a better model when we start to see how one episode of teaching requires prior knowledge to not only reinforce memory but to access new learning.

However, teaching one unit and then returning to some of the core knowledge of that unit later as a bolt-on exercise in retrieval practice is unlikely to have the desired effect of creating strong schematic models for students.

The approach we take in activating prior knowledge needs to pay service to the internal dynamics of our subjects. These are complex, transformational and symbiotic.

- How to design a carefully sequenced primary history curriculum

- Creating a primary plan for history, geography and RE

- Secondary maths curriculum development at Ormiston Academies Trust

Digging deeper

When returning to key knowledge, we must undertake a revisiting that digs deeper than simple retrieval. We need to explicitly draw attention to where we have seen this vocabulary, concept, behaviour or pattern before. Then we need to expose its relationship to what we are teaching now.

It’s a process that involves foreshadowing, reference, embellishment, echoes and evolution. It’s a continuous ebbing and flowing between the simple and the esoteric, rather than a mere layering of one building block on top of the other. This could be as simple as using signposting statements:

- Where have we seen this before?

- What does this remind us of?

- How does this have a relationship with what happened previously?

- How does our understanding of the previous concept inform our understanding of this one?

To sequence our curriculum in a way that is sensitive to, and prioritises these internal dynamics, we need to have some understanding of how this works in our subject and how we can harness this when designing our curriculum.

Knowledge structures

To understand the relationship between the components of our curriculum, we need to consider how structures of knowledge affect their sequencing.

For the purposes of curriculum sequencing, we can broadly divide knowledge structures into those which are hierarchical and those which are cumulative.

Subjects may be more hierarchical than others or more cumulative, but to define them as distinctly one or the other would be to oversimplify the nuances of these definitions and the subjects they apply to.

Broadly, we may consider subjects such as English literature, geography, history, art, drama and music as more cumulative than hierarchical. This is because there are fewer threshold concepts that require one component being taught before the next. Although units of study may be related, they are less likely to be reliant on each other for understanding.

However, subjects with more cumulative structures still benefit from unifying principles to reinforce an understanding of the subject discipline.

Kat Howard (@SaysMiss) is a senior leader at the Duston School, Northamptonshire. Claire Hill (@Claire_Hill_) is trust vice principal and secondary improvement lead at Turner Schools in Kent. This article is based on an edited extract of their book, Symbiosis: the Curriculum and the Classroom (John Catt, £14).

Using cognitive science to plan humanities

Unlock understanding for primary pupils by using the key concepts of cognitive science to organise your humanities curriculums, says assistant headteacher Marc Hayes…

Imagine this. You’ve spent hours on your latest unit of work, done a ton of research, identified potential misconceptions, created beautiful resources… and by the end of the unit, the children still fail to tell you at least five things they’ve learned.

This familiar frustration plays out in primary schools across the land. But why does it happen so frequently? Cognitive science offers us an answer.

What is cognitive science?

It explains that a child’s working memory can only hold three to four pieces of information before being overloaded. For content to be stored in long-term memory, a child must spend a substantial amount of time thinking about it. They must also consider it repeatedly over time.

Teaching new content in bitesize chunks and reviewing it afterwards until pupils have memorised it are two important principles for effective teaching and learning.

However, with so much content to cover – especially in the humanities subjects – this can be a real challenge. Considering curriculum sequencing can help. The way we structure and sequence teaching units has a significant impact on what children learn.

By thinking about how content builds on prior knowledge and returns to key concepts, we can unlock opportunities to support memorisation. This makes our teaching more effective, as pupils develop their understanding and make meaningful links to what they already know.

“The way we structure and sequence teaching units has a significant impact on what children learn”

At my school, we’ve been working on making content more memorable for a number of years. We’ve tried being more specific with the content. And regular retrieval practice. We’ve also tried finding high-quality texts and reading them repeatedly.

All have had some impact. But we still found that children’s ability to discuss their learning in their own language and on their own terms was quite limited.

Trending

Considering the curriculum sequencing more carefully – especially referring back to similar ideas throughout a unit –has, however, had some promising effects. We feel now that children are more able to articulate what they have learned and more easily give examples.

Here are three ways in which you could sequence content in humanities over different periods of time…

History

A key idea of Ancient Egypt is the concept of pharaoh. If children have one lesson on Egyptian monarchs, their understanding is likely to be limited. They may remember that pharaoh is the name for an Egyptian king or queen – a concept that’s already familiar to them, so is easier to remember.

They may also remember some catchy names like Tutankhamun or Cleopatra. But if we give all the more ambitious content about pharaohs in one lesson, they are unlikely to be able to recall it all later.

Instead, we can return to the concept over a series of lessons. We can understand pharaohs in terms of their position in the social hierarchy when exploring Ancient Egyptian society; their divinity when exploring Ancient Egyptian religion; and how their tombs can help historians understand this period of time.

Returning to the concept not only enforces the definition of pharaoh, but it also develops children’s conceptual understanding – their schema.

By structuring content to make repeated links back to the core knowledge of the curriculum, we can not only prevent forgetting but actually deepen understanding.

Geography

Some concepts in the humanities are massive and really do require more teaching time than we might first think.

I used to think children could learn about climate in a couple of hour-long lessons. How wrong could I be? Whilst previously I might have been happy with my children being able to parrot that ‘climate is the average weather of a place’, I’ve become increasingly bothered that not only is this a superficial understanding, it is also next to meaningless without rich examples underpinning it.

It’s important to remember that the national curriculum describes the ‘outcomes’ of teaching sequences. For something like climate, the outcome – being able to understand climate as a concept – is a consequence of learning about its many components and thinking about how they are related.

“We can always find ways to improve and optimise our teaching sequences at every level”

For children to achieve this outcome, they will need to have learned about weather, the water cycle, the sun’s intensity at different latitudes, climate zones, the relationship between climate and biome and why certain vegetation grows in certain parts of the world.

Embedding these components in different units of study across KS2 is one way to provide sufficient examples of a concept without overloading children in a single lesson or series of lessons.

It’s important, however, to make sure pupils are aware of how all the components connect to the central concept.

RE

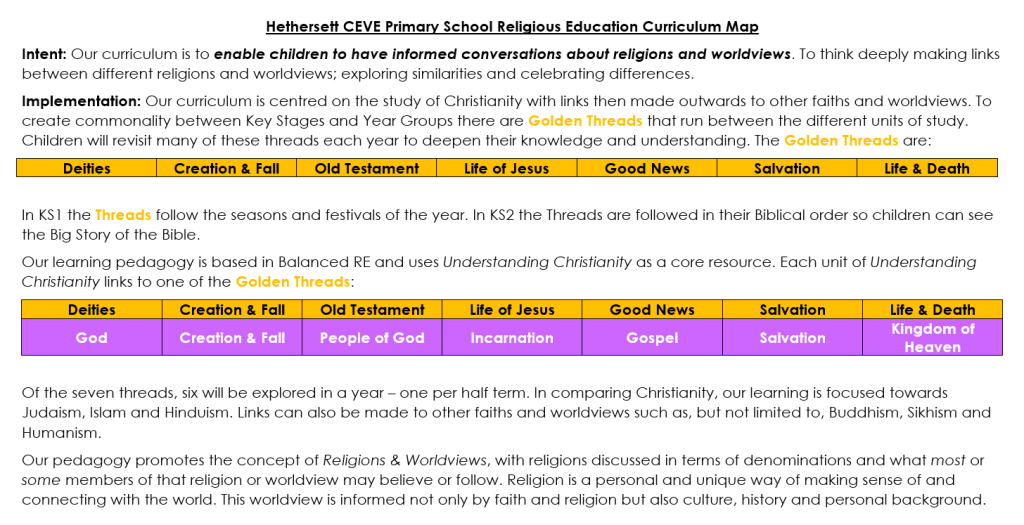

Whatever the local specification for RE, determining what content to teach is a substantial task for any RE leader. To gain a rich understanding of the many concepts we might teach, we need to return to them time and time again, using meaningful examples to illustrate key components.

Whoever designs the RE curriculum at your school can support you to achieve this by setting out the content required for each year group. Also, importantly, they can describe how that content links to and builds on what children have already learned.

This RE curriculum map from Hethersett CEVE Primary encourages pupils to make links between different religions/worldviews

Take, for example, the concept of forgiveness in Christianity. Children in KS1 may learn that forgiveness is a core Christian belief and hear stories such as the Prodigal Son. In KS2, pupils might return to the concept of forgiveness. However, they’ll approach their learning with increased sophistication, going into more depth.

Returning to a familiar story gives children the chance to extend their understanding of what that story means for Christians. Afterwards, they could learn about other important stories, such as Joseph and his brothers. This is useful once they have practised the more sophisticated content about forgiveness in a familiar context.

We can always find ways to improve and optimise our teaching sequences at every level. When you’re next reviewing your subject, planning or teaching materials, it can be a good idea to think about how the content fits together. This supports children to remember more of what you’ve taught them.

Cognitive science glossary

Working memory

This is the part of the brain that holds and manipulates information while we think. It’s a bit like the brain’s workspace. Like a physical workspace, it becomes difficult to think effectively when there is too much going on.

Cognitive scientists suggest that working memory can typically hold three to four pieces of separate information before becoming quickly overloaded. They also suggest that we can hold information for about 30 seconds before we lose it, unless we rehearse it.

Long-term memory

This is where the brain holds information for long periods of time. If children have information in their long-term memory, we can class them as having learned it.

LTM is stable and somewhat infinite in its capacity. Retrieval practice strengthens memories.

Cognitive overload

This is where the working memory has too much to think about. Unfortunately, it isn’t limited to curriculum content. It includes any sensory information such as sights and sounds, including any background noise and distractions.

We should try to reduce any sensory information which is non-curriculum content to optimise learning for our pupils.

Marc Hayes is a Y6 teacher and assistant headteacher for primary curriculum at Roundhay All-Through School, Leeds. Follow him on Twitter @mrmarchayes and see more of his work at marcrhayes.com