Disciplinary literacy – what it is and how to teach it in primary

Subject-specific reading and writing is about more than knowing the right words, argues Shareen Wilkinson…

Over the past few years, I have heard several discussions of and references to disciplinary literacy in secondary schools, but what is it, exactly, and how can we embed it in primary schools?

Professor Timothy Shanahan (University of Illinois at Chicago) defines it as ‘the specialised ways reading, writing, and oral language are used in academic disciplines such as science, history, or literature’ (‘Disciplinary literacy in the primary classroom,’ 2019).

Disciplinary literacy goes beyond producing a diary from the point of view of an historical character, and focuses on what writing might look like in a particular subject.

For example, in history, you might be teaching about primary and secondary sources. This is different to generic reading comprehension strategies in English (e.g. making predictions, asking questions, and clarifying the meaning of unknown words), which might be a requirement for reading in general but is not specific to history.

In other words: ‘Each field of study has its own special ways of using text to create, communicate, and evaluate knowledge.’ (Shanahan, 2019).

For those of you wanting to develop pupils’ disciplinary literacy across the curriculum, here are five key approaches to try.

Literacy skills

In many ways, especially for primary schools, there are basic grammar and punctuation aspects needed for all types of writing; for example, capital letters and full stops.

Ensure pupils are competent at these, before embarking on detailed aspects of the purpose and audience for writing.

As Shanahan (2019) explains, subject-specific (or disciplinary) literacy requires more than the ‘general literacy skills that can be applied in all subjects,’ but also includes the ability to ‘apply both these general and specialised skills in sophisticated ways’ within various disciplinary contexts.

Thus, we need to emphasise the importance of general literacy skills, including decoding for reading, first and foremost.

Age appropriate approaches

This is particularly pertinent for younger pupils. Of course, we are not expecting our littlest children to be knowledgeable and competent in writing and reading like an historian, but we can ask them disciplinary questions and expose them to disciplinary texts.

For example, perhaps during reading time, try asking: ‘What do you think is going to happen next in the story?’; ‘Have you read a book like this before?’; or when they’re playing: ‘How are these toys similar or different to your toys?’ etc.

This will introduce them to historical approaches without requiring them to have knowledge they won’t engage with until later in their school journey.

Teacher CPD

We all know that primary teachers are not always experts in every subject they teach. I still draw like a six-year-old – although learning how to observe like an artist has helped in recent years!

I would have benefitted from this approach in the past. Many of us must juggle and/or lead more than one subject at a time.

One of the best ways you can tackle this is to carry out an audit of current knowledge and understanding and to ensure all staff have access to high-quality networks, such as being a member of the subject associations.

This will, inevitably, help with the development and understanding of disciplinary literacy.

Tier 3 vocabulary

There are certain words across the curriculum that are pertinent to a particular subject. For example, to ‘take away’ means something very different in maths, to a ‘cheeky takeaway’ on a Friday night!

Provide opportunities for pupils to understand what key terms are across the disciplines you teach.

They should understand any synonyms or antonyms, the definition (through multiple exposure to the word) and the etymology (or word origin) of important terms.

Subject knowledge

A key step to embedding disciplinary literacy across the school is to know and understand what reading, writing, and thinking looks like in different subjects.

This is challenging, and so curriculum leaders should be given the opportunity – and time – to explore this within their own subjects.

Many elements have been outlined in the National Curriculum and Ofsted research reviews already, so it’s just a case of finding them. I’ve also included some examples at the end of this article.

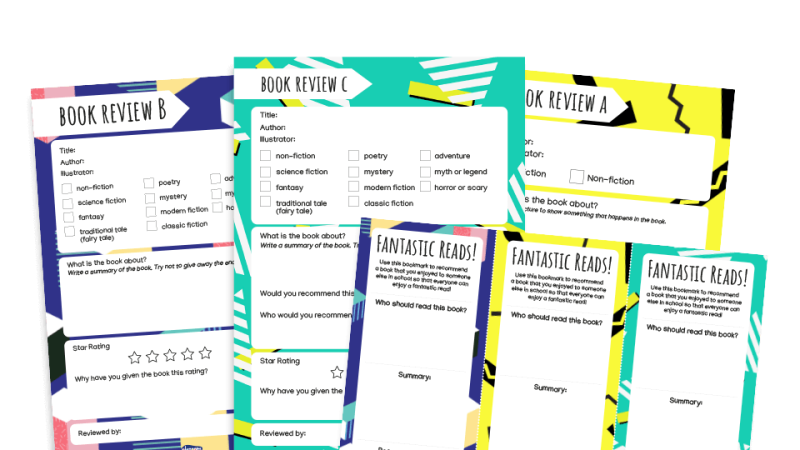

Once subject leaders are clear on what literacy looks like in their area, it is helpful to produce posters and resources, so they can begin to embed what they’ve learned in their lessons.

Hopefully, these five ways will support you with making a start with disciplinary literacy.

Remember, it is not about changing everything, but exploring where opportunities can be embedded within your existing provision.

Disciplinary literacy in practice

- English

Although we want to develop reading, writing, and thinking across the curriculum, it is pertinent to start with English because it has its own unique discipline that pupils need to master before they can tackle other subjects.

Perhaps one of the most researched ways to improve reading is to embed reading comprehension strategies.

How to read for comprehension:

- Make predictions (based on text content and context), e.g. I predict that…

- Ask questions. E.g., I wonder why…

- Clarify the meaning of unknown words. E.g., I am not sure about….

- Summarise the text

- Activate prior knowledge. E.g., This reminds me of….

Key aspects for writing in English:

- Prewriting activities that support oracy

- Vocabulary development

- Identifying key text features (e.g. genre and specific vocabulary, figurative language, punctuation and grammatical devices)

- Writing for a particular audience and purpose

- Drafting, revising and editing

- Sharing, reading, and editing each other’s work

Sources: EEF Improving literacy at KS1 and EEF Improving literacy at KS2

Chambers, A, Tell Me (Children, Reading and Talk) with the Reading Environment, (Thimble Press, 2011)

- History

When reading in history, make sure you’re providing opportunities for pupils to explore primary and secondary sources, and to recognise similarities and differences.

Reading, writing and thinking like an historian:

- Ask and answer questions

- Use historical vocabulary (e.g. monarchy, migration, century, invasion)

- Note connections, contrasts, and trends over time

- Identify change and cause

- Explore similarity and difference

- Define historical significance

- Use sources and evidence

Sources: History National Curriculum and the Ofsted research review (2021)

- Geography

Reading, writing and thinking like a geographer:

- Recognise the interconnectedness of different geographical content

- Think about alternative futures

- Consider personal influence on future climate decisions

- Make connections, such as: ‘Where is this place?’; ‘Why is it here and not there?’; ‘What is the place like?’; and ‘How did this place change to get to how it is now?’

- Read a range of non-fiction and fiction that broadens pupils’ knowledge of the world

Sources: Ofsted geography review (2021) and the geography National Curriculum

Shareen Wilkinson is an education adviser and primary teaching and learning director for a multi-academy trust. She is also an established educational author and writer. Follow her on Twitter @ShareenAdvice