Ambitious vocabulary – Best activities, games & teaching resources

These engaging vocabulary activities, games and resources will help you enhance your students’ language skills…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Our daily language is full of useful words for everyday situations, but to be able to communicate clearly in very specific situations, we need an ambitious vocabulary at our fingertips.

Teaching vocabulary is obviously important, as recognised by the national curriculum, but it takes creative thinking to ensure that lessons aren’t just list-learning exercises.

A playful approach to vocabulary that explores jokes, wordplay, riddles and games can help children to better understand the words that they need to use while still having fun.

Help children to learn to love language and develop a thirst for discovering and uncovering new possibilities for themselves with these ambitious vocabulary resources, activities and classroom games.

Ambitious vocabulary resources for primary

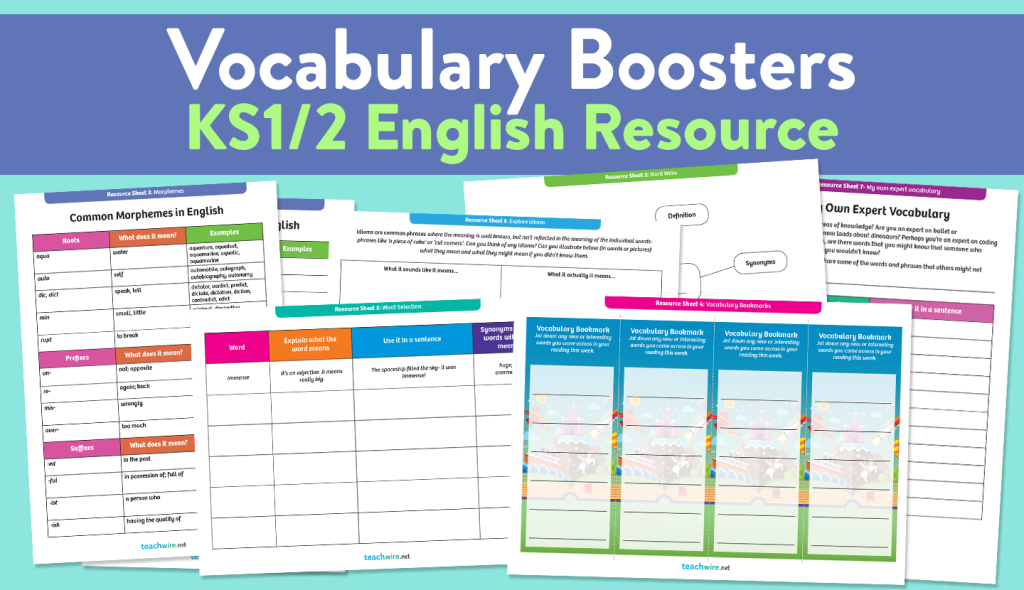

Free vocabulary worksheets

Helping children to develop an ambitious vocabulary is one of the best ways we can support their education. This resource contains seven practical ways to go about it and an accompanying vocabulary worksheet for each idea to download and use in your classroom.

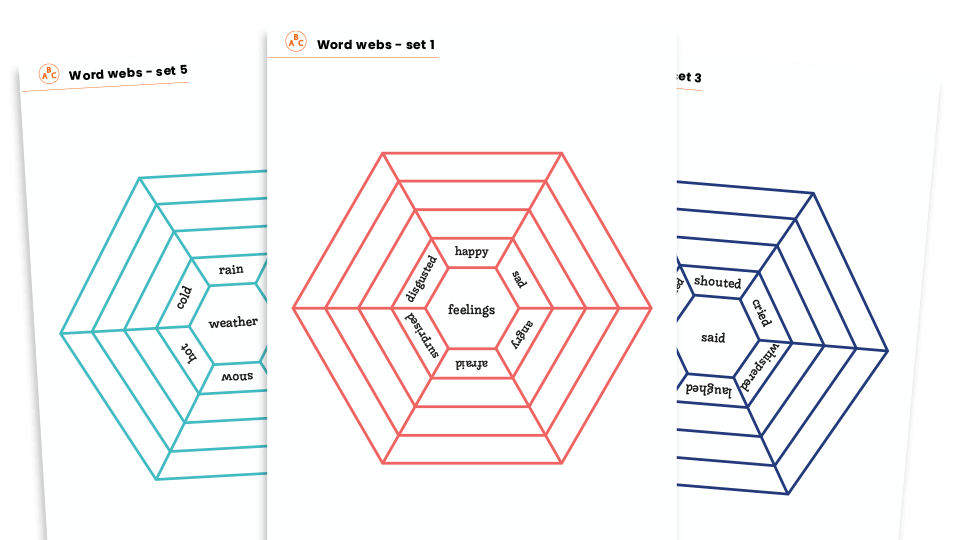

Word webs

Encourage children to explore more powerful vocabulary when writing with these fun vocabulary game resources from literacy resources website Plazoom.

Using either the blank version or a partly filled web, ask pupils to find synonyms of words and add them to the correct parts of the pattern.

Vocabulary marketplace lesson plan

Imagine if words had a value and children could buy or sell them

This free KS2 vocabulary lesson plan from award-winning teacher Adam Parkhouse involves a flexible vocabulary bartering activity in an imaginary marketplace.

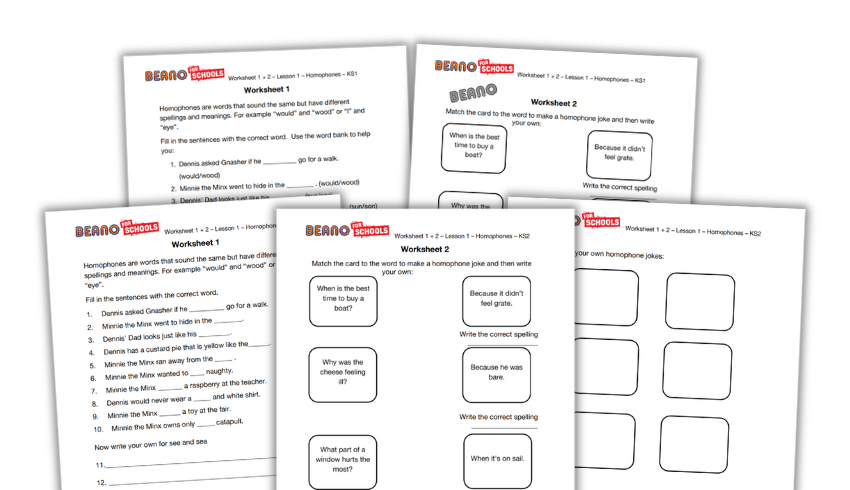

Learn different homophones through jokes

The Beano‘s SPaG LOLZ programme for primary schools covers six key spelling, punctuation and grammar topics with six curriculum-based lesson plans each for KS1 and KS2.

These lesson plans focus on joke-writing techniques taught through SPAG. They’re designed to help learners hone their comedy skills and inject some fun into literacy lessons.

The first lesson in the series focuses on homophones. Download a KS1 version and KS2 version. And here’s a homophone-based joke to get you groaning:

Did you hear about the farmer who sprayed his chickens with perfume? He couldn’t stand the fowl smell.

Paired reading vocabulary worksheet

Use this vocabulary worksheet for your mixed-ability paired reading. It helps pupils work through the process of clarifying vocabulary with which they’re unfamiliar.

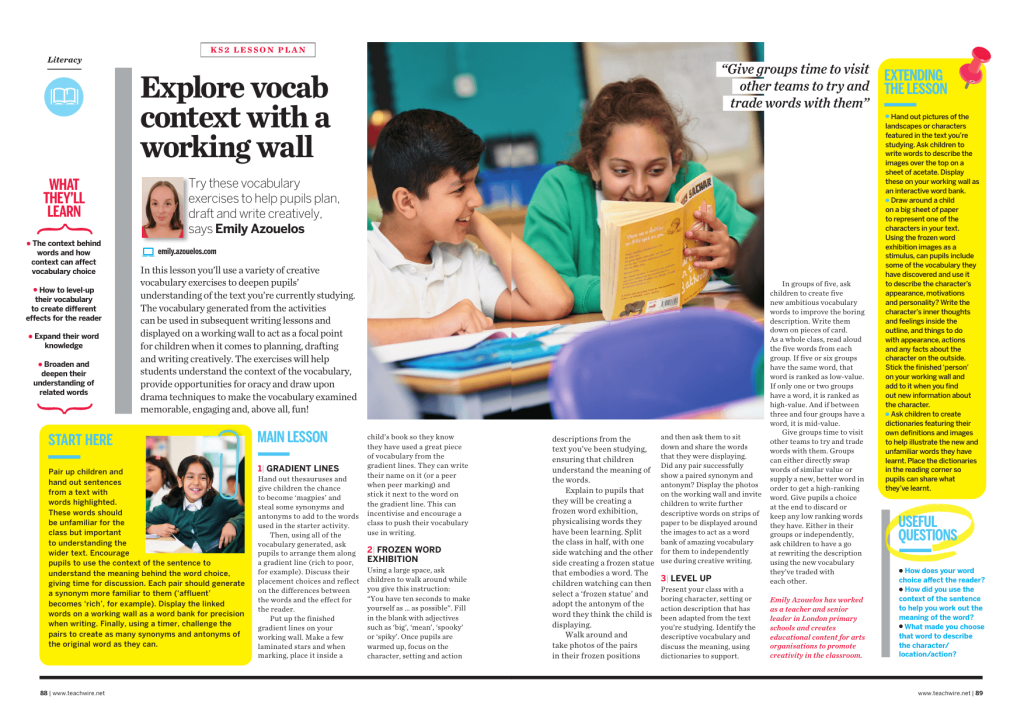

Working wall ideas

In this lesson, you’ll use a variety of creative vocabulary exercises to deepen pupils’ understanding of the text you’re currently studying.

Display the vocabulary generated on a working wall to act as a focal point for children when it comes to planning, drafting and writing creatively.

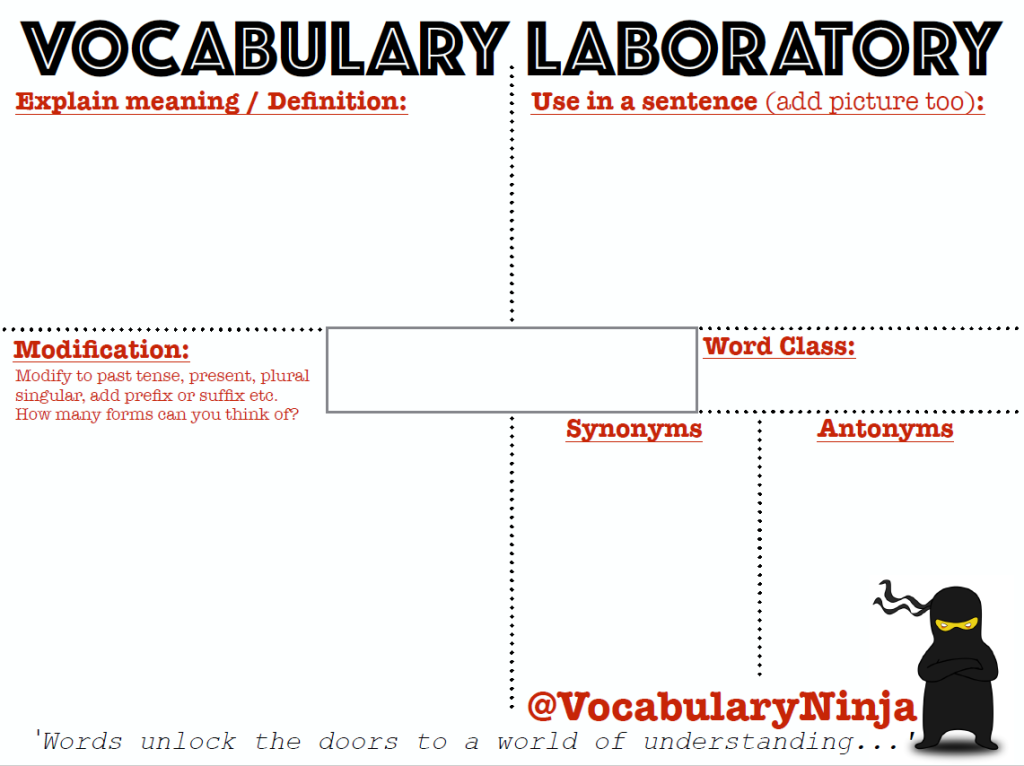

Vocabulary laboratory

Break down any word to its most essential elements with this Vocabulary Laboratory resource. It’s perfect for exploring word class, synonyms, antonyms and understanding.

Ambitious vocabulary resources for secondary

KS3 English lesson plan

Encourage students to develop their vocabulary through these thoughtful and creative activities from Caroline Parker.

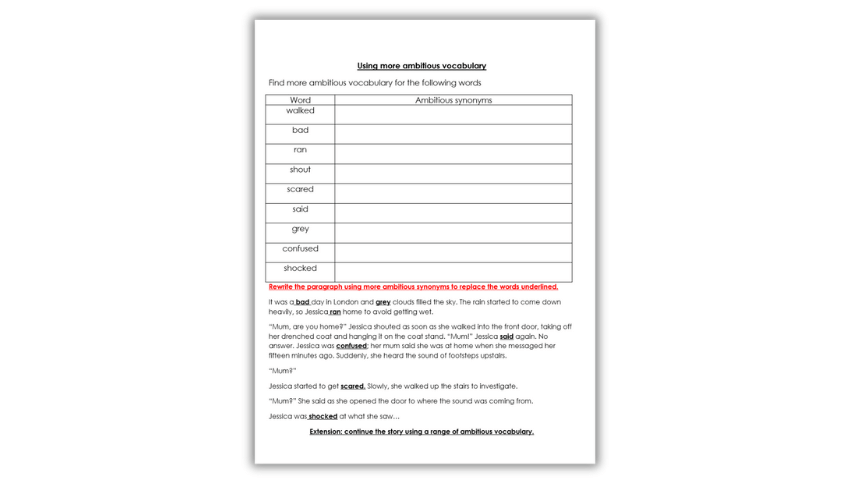

Ambitious vocabulary worksheet

The activity on this vocabulary worksheet encourages students to seek out elevated synonyms for commonplace words such as ‘walked’, ‘bad’, ‘shout’, ‘scared’, ‘said’, and ‘confused’.

By setting pupils this task, you’ll prompt learners to explore the depth and breadth of the English language, expanding their vocabulary repertoire and enhancing their expressive capabilities.

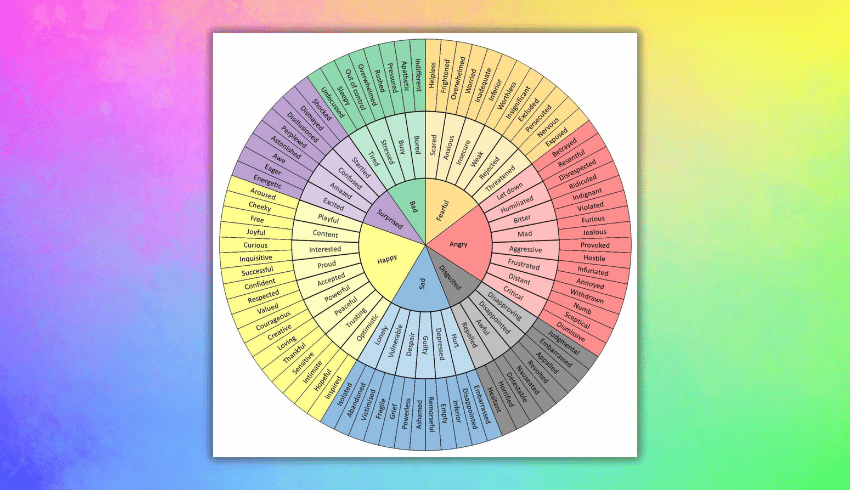

Emotion wheel

This emotion wheel covers seven main emotions. These are then broken down into more and more nuanced synonyms. For example, Angry > Let down > Betrayed.

Discuss each emotion category and encourage students to contribute their own examples, then ask students to write their own descriptive paragraphs, short stories or dialogues using the emotional vocabulary.

Graveyard of deceased vocabulary

This vocabulary display includes a sign for a vocabulary graveyard and six gravestones for ‘dead words’ to avoid using (happy, sad, cold etc). There are accompanying bats for each gravestone with synonyms for each of the dead words.

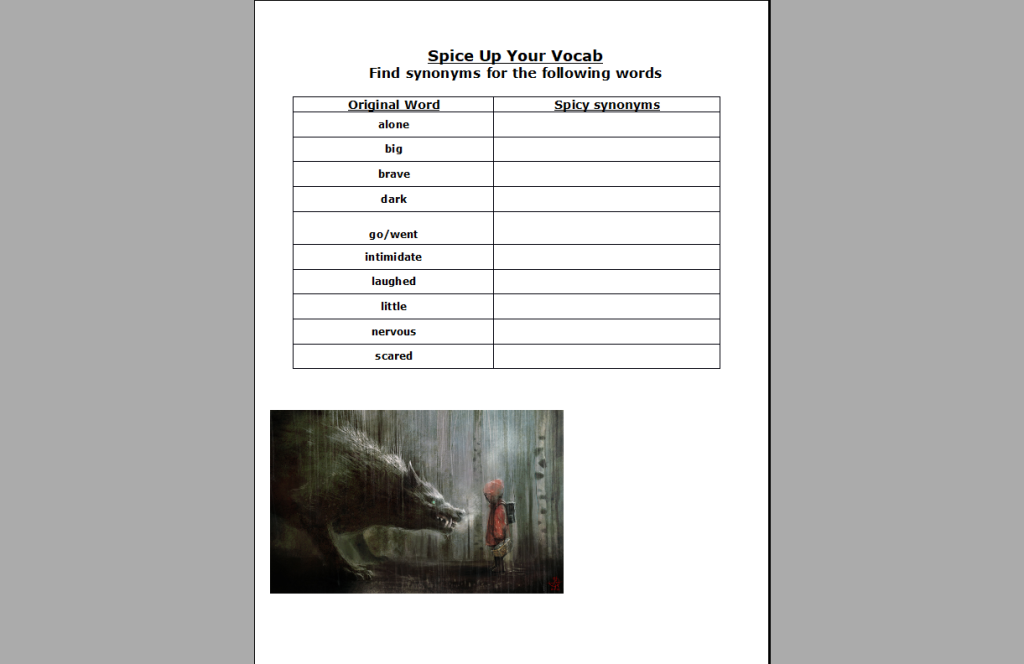

Spice up Little Red Riding Hood

This simple activity asks students to find more creative synonyms for typical words found in the Little Red Riding Hood fairytale, such as alone, big, brave, dark, go, went and scared.

Vocabulary games to play

Play Pointless

Setting up

Decide on a category (eg modes of transport) and generate a list of ten answers.

Assign up to 15 points for obvious answers such as taxi, van, lorry; 5 to 10 points for less obvious answers such as limousine, horse and cart, cruise liner; and 1 to 5 points for more obscure answers like rickshaw and steamer. Assign 0 points to a word you do not think children will come up with (penny-farthing, for example).

Alternative categories

- Places you might live in, eg flat, cottage, semi-detached, bungalow, end terrace, shack, castle, tent

- Things you wear on your feet

- Flower names

- Animals that begin with the letter “s”

- Synonyms for overused verbs (such as eat, walk, sleep, go, sit), adjectives (such as big, red, hot) or adverbs (fast, happily, suddenly)

- Job roles that end in -er / -cian

- Words that end in -ful

Keep categories as tight as possible to ensure children can see the links.

How to play

In pairs or small groups, ask children to write down as many modes of transport as they can think of in two minutes. They then choose three that they think will be on your list, with low points.

Display your pre-prepared list. If children have a transport device on their list that does not match your list, they get 20 points.

The winning team is the one with fewest points at the end of the game. With younger children, you may ask them to pool their ideas and play against you as a class.

Simplify the game by giving children a point for each word they call out that is on your list and keep a more traditional method of scoring (i.e. the more points, the better).

Take time to unpick the vocabulary (you might wish to have images to show the children: “a rickshaw looks like this”). Alternatively, link this game to spelling patterns that you have been studying in class.

Vocabulary 7-Up

‘Vocabulary 7-up’ is a simple game that encourages learners to record as many synonyms as they can for common words (seven ideally!).

So, given ‘positive’, ‘effective’, ‘large’ or ‘small’, students need to exercise their capacity to draw upon a range of synonyms for those words.

This activity assesses their breadth of vocabulary but also overtly signals the necessary variety of words required in academic expression.

Six degrees of separation

Sometimes an old game can come up trumps in the classroom. The simple idea of this one is that all living things in the world are connected by six – or fewer – steps; and it works well enough for making linguistic links too.

Consider the possible lexical steps from ‘abnormal’ to supercilious’. Straight away, pupils need to draw upon their vocabulary knowledge – of synonyms, antonyms, and more – before then drawing upon their personal word-hoard.

Sticky note synonyms

Grab a pack of sticky notes and start labelling! Compete with each other to supply alternative names such as: “looking glass” for mirror; “basin” for sink or “lavatory” for toilet.

Write A-Z lists

Build an A-Z list of objects outside and then indoors. Compete with each other to collect the rarest sightings, from “acorns” to “zebra crossing” and “alarm clock” to “zip”.

How inventive can children be? Descriptive additions could expand opportunities for older children: “blade of grass”, “yellow van”, “comfortable sofa”.

Washing line of feelings

Young children will always tell you they are hungry, cold, cross or bored. Challenge them to generate synonyms for these overused words and create a ‘washing line’ of feelings, pegging them up in order of magnitude.

Words could range from ‘peckish’, through ‘ravenous’ to ‘famished’, or from ‘mildly irked’ to ‘absolutely furious’!

This activity will generate lots of discussion as to where words should be placed. How cold is ‘chilly’ compared to ‘frosty’, for instance?

No room to hang words up? Place words on sticky notes and move them along the scale as you decide where they belong.

Michelle Nicholson is teaching and learning adviser at Herts for Learning, which supports schools and educational settings. Alex Quigley is the author of Closing the Vocabulary Gap.

Dice game for statutory words

Academic words are important to learn and have a place in a rigorous approach to language learning. As children are required to learn to spell the statutory words list of the curriculum, it makes sense to ensure that they also understand what these words mean.

To support this learning, why not encourage children to select a word from the list, roll a dice and complete the activities as follows:

- Write your word in a sentence

- Draw a picture of your word

- Write a synonym of your word

- Write an antonym of your word

- Write a definition of your word

- Write your word 10 times

They could do this with any new spelling lists they need to internalise. It’s still serious word-learning but with a playful twist.

Play ‘Call my Bluff’

You may remember the TV panel show where guests tried to bluff the other contestants by giving them one correct and two incorrect definitions of a word.

It adapts well as a vocabulary game for children in upper KS2 as it’s a fun way to explore word meanings. It provides a chance for children to use their knowledge of puns and wordplay when formulating their bluffs. For example:

‘Artichoke’

- A medical term for blocked arteries

- A vegetable

- An overcrowded art exhibition

- Used to start engines

Play vocabulary bingo

Use bingo boards (or create some with 3×3 grids), and get children to pick nine vocabulary cards from a pack (they should have one word per card). Place them into the spaces on their bingo grids.

As bingo-caller, your role is to read out definitions of words for children to mark off. Once children have three in a row (horizontally, vertically or diagonally) they call ‘bingo’ in the traditional manner.

After you’ve verified that they have the correct words, ask them to choose one and put it into a sentence.

Ambitious vocabulary activities for primary

Write kennings

‘Kennings’ originated in the Norse tradition as a creative way of identifying things without using their name. For example, a cat could be called a ‘mouse chaser’, a goldfish a ‘bowl swimmer’, a teacher could be a ‘homework giver’.

There are some great kenning poems in The Works by Paul Cookson that you may want to explore with your class. Asking children to write kennings about family members, or characters from books or history should encourage them to take a playful look at the vocabulary they use in their descriptions.

Grade synonyms along a continuum

Word scales (or clines) are a good way for children to grade synonyms, and therefore gain a sense of how to use words effectively in their writing.

Start by providing children with synonyms for words that they may overuse such as ‘sad’, ‘happy’ or ‘nice’.

It’s often better to provide them with the alternatives (for example, downhearted; gloomy; melancholy; exasperated desolate; inconsolable) rather than ask them to generate their own.

This is because often they may not know many synonyms, or they will only know the extremes which can lead to ineffective choices when used in their own writing.

Now ask them to grade the synonyms along a continuum. There is no absolute answer, and the different clines created by members of the class will offer interesting opportunities for further research and debate.

Rachel Clarke is the director at Primary English Education. She works with schools nationally and internationally, training on all areas of primary English but most frequently on creative ways to teach grammar, spelling and vocabulary.

Hexagonal learning

Write target words onto hexagon shapes. Encourage children to physically connect hexagons by articulating how words are related (eg by meaning, sound or visual features).

Word web

Start with a target word and create a ‘web’ of connected ideas (mind map). Link words with the same or similar meanings (synonyms), words that mean the opposite (antonyms), and other ideas or related contexts.

Noughts and crosses

Are you ready for the O & X challenge? Set up a game board with familiar target words written in each section of the grid.

To ‘capture’ the square, get pupils to share a personal connection with the chosen word – what do they think of when they hear it?

Word riddles

Come up with a word-themed riddle to describe a target word. For example, for playtime you might write: “This word has two syllables. It is made up of two root words. The first root word rhymes with stay. We have this every day in school.”

Kelly Ashley is a freelance English consultant based in Yorkshire and author of Word Power: Amplifying Vocabulary Instruction. See more of her work at kellyashleyconsultancy.wordpress.com.

Ambitious vocabulary activities for secondary

Regular quizzing

Regular low-stakes quizzes can represent a useful tool for consolidating vocabulary knowledge – one that is low-stress and low-effort for teachers and pupils.

Our students need to repeatedly revisit and consolidate terminology if they are to grasp a deep knowledge of a word or phrase.

Quizzing then needs to be cumulative, far beyond when we first study curriculum content, with vocabulary appearing in three or more quizzes, over an increasingly spaced period.

Word triplets

The ‘Word Triplets’ strategy offers students three words to choose from (or synonyms) so that we can begin to shape their apt vocabulary selections.

In history, for example, you may offer students the choice between ‘possibly’, ‘perhaps’ and ‘certainly’ to describe a specific source. Students then select from the triplet and have to use the word and justify its use.

By offering up potential answers, you let students concentrate on precise word choices, thereby honing their writing skill.

Make meaning maps

If you are teaching a tricky new word like ‘photosynthesis’ then you can make a ‘meaning map’ – unpicking the word, explaining its origins, and linking it to similar scientific words.

Working subject glossaries

A word list can prove inert, but by beginning a topic or course with a blank slate of key words and encouraging students to enquire around their meanings, you can invoke curiosity and deeper understanding.

Alphaboxes

Simply create an alphabetical list, organised into boxes, and encourage students to populate the ‘alphaboxes’ with essential subject vocabulary.

Word of the week

Every subject can promote a habitual interest in words by sharing their ‘word of the week’ or having ‘word walls’ that create an omnipresent interest in academic vocabulary.

Best vocabulary-building books

Little Mouse’s Big Book of Fears by Emily Gravett – This book is wonderful for learning about the etymology of words such as arachnophobia, hydrophobia, chronomentrophobia and more.

The Silly Book of Weird and Wacky Words by Andy Seed – This is crammed with puns, jokes, riddles and idioms.

13 Words by Maira Kalman and Lemony Snicket – Like most traditional vocabulary books, this one introduces a new word on each page. But in a twist on the traditional format, the introduction of the adjective ‘despondent’ as the second word ensures that a narrative develops using the 13 words introduced in the book.

Mom and Dad are Palindromes by Mark Shulman – Recognising palindromes isn’t a requirement of the national curriculum, but they are such great fun they should be explored by all children. This books does just that and includes over 100 palindromic words, phrases and sentences through a fun illustrated text.

Traction Man is Here by Mini Grey – This book couples lively illustrations with humour and clever wordplay. The vibrant, engaging illustrations help the reader begin to unlock the meaning of unfamiliar words such as ‘sieve’, ‘suffocate’, ‘overgrown’ and ‘mysterious’, words they are unlikely to encounter in everyday exchanges.

Browse our range of spelling games.