Teaching writing – How to create motivated writers

Let’s bring motivation, enjoyment and authentic writing purpose back into our classrooms, say Ellen Counter and Juliet McCullion from HFL Education…

Writing is a hugely complex and demanding skill. Not only this, but it places great demands on our emotional resources alongside the cognitive requirements.

As teachers, we place writing demands on children every day in school. To do something so demanding, pupils need to feel that writing is a worthwhile pursuit.

They have to be motivated, volitional, autonomous and confident writers. If they are going to leave a little piece of themselves on the page – an insight into their identity for scrutiny – then there had better be good reason to do so.

As Young & Ferguson state: ‘Emotionally healthy young writers are able to produce better texts because they have secure writerly knowledge (cognitive resources) to draw on, they know how to manage the processes involved in writing, and they can use and apply a variety of writerly techniques’.

We know that there has been a stark decline in the percentage of children and young people in the UK who are volitional writers.

In June 2023, the National Literacy Trust produced results from its latest survey. This showed that only 34.6 per cent of children and young people aged between eight and 18 enjoyed writing in their free time. In 2023, 71 per cent of pupils met the expected standard in writing, down from 78 per cent in 2019.

The good news about teaching writing

Despite these gloomy figures, there is hope. An increasing demand for research-informed writing teaching is blossoming. This is led by the clarion call of Ross Young & Felicity Ferguson at The Writing for Pleasure Centre and other hugely influential academic researchers.

In a recent article, written by Debra Myhill, Teresa Cremin and Lucy Oliver, the authors suggest that there is a distinct lack of empirical evidence concerning what constitutes teacher subject knowledge for writing.

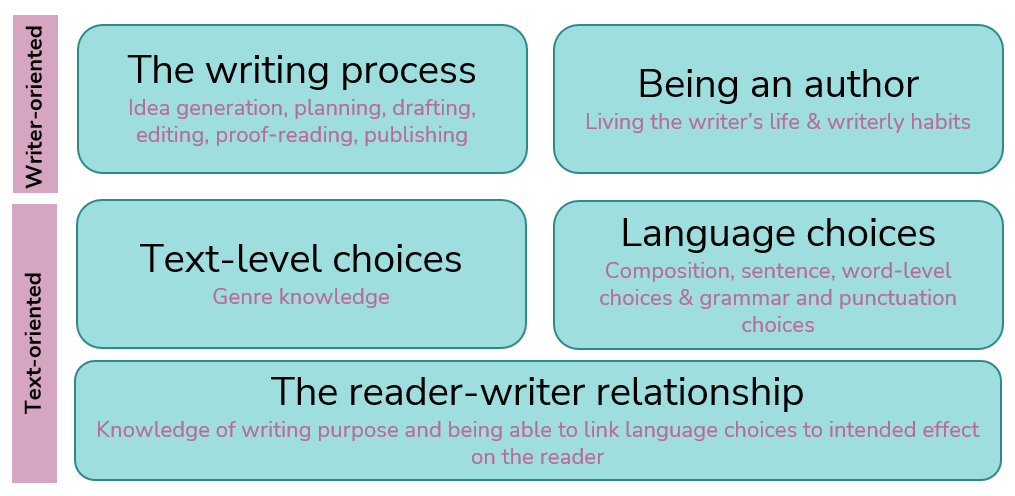

They propose reframing writing as a ‘craft’ rather than a subject, and suggest five key themes of writing craft knowledge. We’ve outlined and expanded on these in the panel overleaf.

Whilst we cannot go into details for all of these areas, let’s briefly focus on the three text-oriented themes:

- the reader-writer relationship

- language choices

- text-level choices.

In other words (and this is a huge simplification!) how can we write effectively based on our purpose for writing and how we want our reader to feel/think/do/understand. And what language and text choices can we select to do this?

The national curriculum currently does not help teachers to understand the craft of writing. Statements such as: ‘In narratives, create characters, settings and plot’ offer up no guidance as to how a writer would go about bringing a character to life, or the techniques writers use to construct a vivid setting.

This lack of direction often leads to writing being skewed towards box-ticking of grammar terms and punctuation (sometimes leaving out the craft of composition entirely).

The authentic craft of writing therefore, in many classrooms, remains a mystery to all involved.

However, within its aims, the national curriculum does emphasise the importance of an awareness of purpose and audience.

There are various suggestions for a range of writing purposes. We could broadly categorise them as writing to: entertain, inform, persuade and discuss.

Writing techniques

Michael Tidd has previously blogged about his approach to devising a writing curriculum using these four writing purposes. Of course, these can overlap, but there is usually an overriding one at play.

Carefully constructed writing curriculums should support children in building an understanding of writing for different purposes. They should enable them to connect with their audience as a writer, and provide them with opportunities to make choices about their writing.

When pupils start to notice that different writers use similar writerly techniques according to their writing purpose, they can start to build writing schemas alongside a developing understanding of genre knowledge.

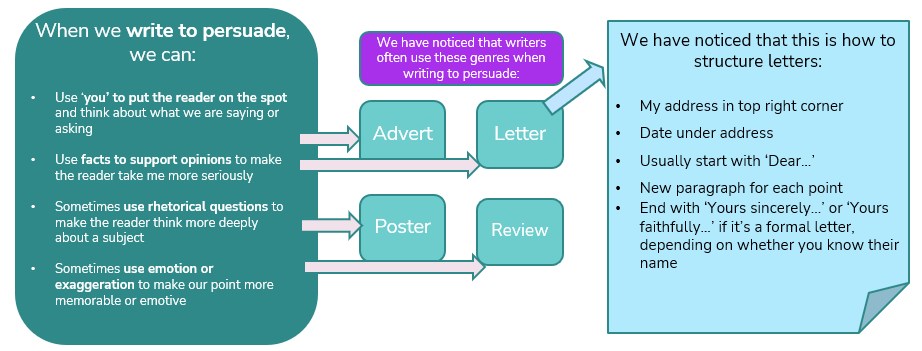

For example, pupils can observe that when writing to persuade, we often:

- Use ‘you’ to put the reader on the spot and think about what we are saying or asking.

- Use facts to support opinions.

- Sometimes use rhetorical questions to make the reader think more deeply about a subject.

- Sometimes use emotion or exaggeration to make a point more memorable or emotive.

When they notice that writers often use adverts, letters, posters or reviews when writing to persuade, they will be able to match appropriate persuasive devices and genres for their writing purpose.

Putting it into practice

Curriculum design and teaching writing should therefore be carefully crafted to allow children to recognise that their language choices do not exist in a vacuum, and they can return to their knowledge of writing purpose to transfer this into different contexts (such as a variety of genres) and make links to any new learning. Not only within English lessons, but across the curriculum, with conscious control and choice.

Of course, we need to combine an understanding of both the cognitive and emotional demands that are placed on children when they are learning to write. Both domains must inform our decisions when creating any sort of writing curriculum within schools. We must include children in the decision-making concerning their writing – making writing an enjoyable experience for them along with feeling a sense of satisfaction in their own high-quality creations (Young & Ferguson, 2021). As Michael Rosen states in his ‘Did I Hear You Write?’ (1989, p. 43): ‘…language doesn’t have to seem like A Thing; something that doesn’t belong to you; or something that isn’t part of how you think. Rather, it is a way of thinking you can control’.

Ellen Counter has had 17 years of primary teaching experience, working in three different London boroughs. She has enjoyed teaching every age group during that time – from Nursery to Year 6. She completed her MA in Children’s Literature in 2013 and is now a Primary English Teaching and Learning Adviser with HFL Education.

Juliet McCullion is a former primary school teacher. She is now an enthusiastic primary English teaching and learning adviser for HFL Education.

Get the latest news from HFL Education at HertsEnglish on X, or HfLPrimaryEnglish on Facebook.

Looking for a writing curriculum?

Plazoom’s Real Writing is a complete writing curriculum for Years 1-6, that puts the highest quality model texts at the heart of great literacy teaching.