Effective behaviour management – It’s less what teachers say but how they say it

Effective behaviour management is anchored less by what you say to students, and more by the meanings produced by your mode of speaking, says Peter Nelmes…

- by Peter Nelmes

Ever wondered what the secret at the heart of effective behaviour management is? I certainly did at the start of my career, as a teacher of children with emotional and behavioural difficulties, back when my classroom was often a place of chaos.

I therefore embarked on a quest to find out what it was that successful teachers were doing to keep their classrooms havens of peace and learning.

I recorded and analysed hours and hours of talk. I thought the answer could be found in teachers’ use of language, so I looked closely for the ‘emotional bits’ but found almost none. The tapes simply sounded like ordinary teaching and learning.

There was nothing to base my doctorate on (the vehicle for my research), nothing to allow me to use to improve my own practice. I was at a loss.

These teachers knew their pupils’ potential for mayhem and worked hard to make sure that problems were avoided – so where was the evidence that they were doing so?

Shared meanings

The eureka moment came when I realised that the assumptions upon which my research was based were wrong.

I had assumed, for example, that challenging behaviour came from the child, and that the promotion of teaching and learning came from the teacher.

I had assumed also that language would be key.

What I came to see is that it’s not so much the language, but rather the shared meanings that lie at the heart of everything.

If a teacher and pupil have jointly constructed a meaning between them – to the extent that they’re on the same page and completely get where the other is coming from – then teaching and learning follow, and the likelihood of challenging behaviour diminishes.

The behaviour comes from the transaction, not from the child. It occurs when those shared meanings break down, and the teacher and pupil cease understanding where the other is coming from, be it cognitively or emotionally.

I realised that everything teachers did, from setting the activity up, to choosing the level of lesson complexity and their style of delivery, was designed to establish and maintain shared meanings with their pupils, so understandings could be reached and anxieties kept at bay.

Their aim was to ensure the pupils could access meanings which built up their sense of competence, a sense of positive identity and a sense of belonging in the classroom.

Through their teaching, these teachers were seeking to contain difficult emotions and counter pupils’ expectations of failure, while promoting success, fun, and above all, hope.

My recordings sounded like straightforward teaching on the surface, but once I understood what was actually going, those same recordings became quite moving to listen to, given the pupils’ histories of exclusions and rejections from other schools.

Facilitative mode

That’s not to say that the language used was sugary sweet; any teacher attempting that approach with these image-conscious adolescents wouldn’t have lasted for more than a few minutes.

Moreover, there were times when boundaries had to be restated, which was done with clarity and firmness.

Hearing this led me to the view that there are four types of teacher talk, each of which affects the nature of the meanings present in our classrooms, as detailed in this table.

| Mode | Explanation | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Facilitative | Teacher and pupil both creating the meanings in class, building a relationship |

|

| Authoritative | Cashing in on your personal relationship with the pupil to achieve compliance by imposing a meaning the pupils chooses to accept |

|

| Authoritarian | Invoking external powers or the power of your position to impose a meaning the child has no choice but to accept |

|

| Excluding | Imposing a meaning upon the pupil which often results in their exclusion or shame |

|

It became obvious that the more time teachers spent in ‘facilitative mode’, the better. In that mode they could use ‘soft’ persuasion techniques, such as humour and warmth, to get the pupils to comply far more effectively than if they had tried to use their authority.

Spending time in facilitative mode enabled them to bank goodwill, meaning the pupils were more likely to comply if and when the teacher had cause to drop down into authoritative mode.

I noticed that when good teachers went into authoritative mode, they worked hard to get back to facilitative mode as quickly as possible, so as to avoid running low on that goodwill.

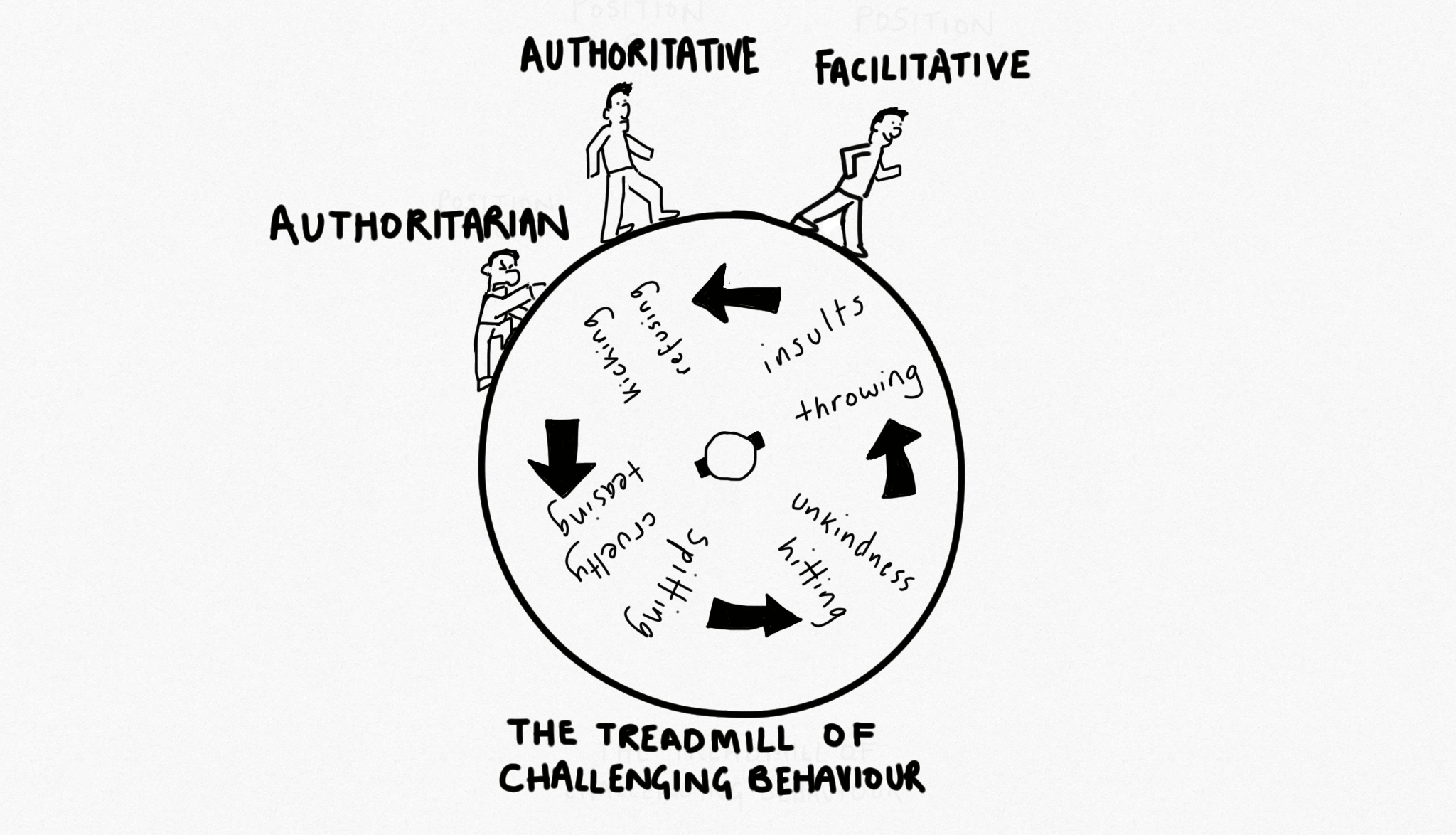

Working predominantly in facilitative mode is vital for teachers’ wellbeing. I picture my own day-to-day teaching as similar to being on a treadmill that turns each day – sometimes quite slowly, but on more difficult days, with a speed that can knock me back a bit (see image below).

On those occasions I must work harder to get back to the top of the wheel, from where I can walk slightly downhill and get a clearer view of what the day is bringing.

What I want to avoid at all costs is being in a position where each day feels like a series of conflicts, an uphill climb and a struggle with the pupils’ and my own emotions.

Behind the wheel

There are many factors that affect your position on the wheel, including how emotionally strong you are and how well your lessons are organised.

How easy or hard you find each day may also depend on how aware your pupils are of the extent to which you like and celebrate them.

Ask yourself how achievable and fun your activities are. Is the curriculum relevant, and how well can you repair breakdowns in understanding?

Consider also the clarity of your expectations around behaviour, and the extent to which you’re able to cultivate positive relationships with parents.

Other factors affecting how hard the wheel is to deal with can include the amount of help you receive from colleagues, your deescalation and problem prevention skills, and whether you consistently follow up problems with fairness and respect.

If there’s a pupil in your class whose behaviour is giving you problems, listen to yourself the next time you speak to them. Chances are you’ll be using less facilitative talk than usual. If you can find a way to remedy that, the pupil’s behaviour will change for the better.

Peter Nelmes is a senior manager in a special school and is the author of Troubled Hearts, Troubled Minds: Making Sense of the Emotional Dimension of Learning