SATs 2026 – The ultimate teacher guide to preparing pupils for Key Stage 2 assessment

How to prepare pupils for this year’s SATs and make sure they get the scores they deserve…

- by Teachwire

Whatever your thoughts and feelings are about SATs, and tests in general, naturally you’ll want your pupils to do as well as possible, without causing them any stress or worry along the way.

We’ve picked out a selection of resources that can help consolidate children’s learning and prepare them for KS2 SATs, without making it feel like a big, dark educational cloud is looming on the horizon…

(We also have a post about the optional KS1 SATs).

Table of contents

When is SATs Week 2026?

KS2 SATs are due to take place between Monday 11th May and Thursday 14th May 2026.

The timetable is as follows:

| Monday 11th May | English grammar, punctuation and spelling papers 1 and 2 |

| Tuesday 12th May | English reading |

| Wednesday 13th May | Mathematics papers 1 and 2 |

| Thursday 14th May | Mathematics paper 3 |

When are SATs results 2025 announced?

Headteachers can view results from 7th July 2026. Parents will also receive results around this time. Schools’ performances will be made public in December 2025.

SATs scaled scores 2026

The government will make scaled scores for 2025’s SATs available in July 2026.

KS2 SATs access arrangements

Some pupils with specific needs may need additional arrangements so they can take part in the 2026 KS2 SATs.

This could include, among other things, additional time to complete the test, the use of electronic aids or the use of rest breaks.

Read the government’s guidance for schools about access arrangements here.

KS2 English SATs resources and advice

KS2 English – SATs practice tests

You can find KS2 past papers from 2023-2025 on the government website.

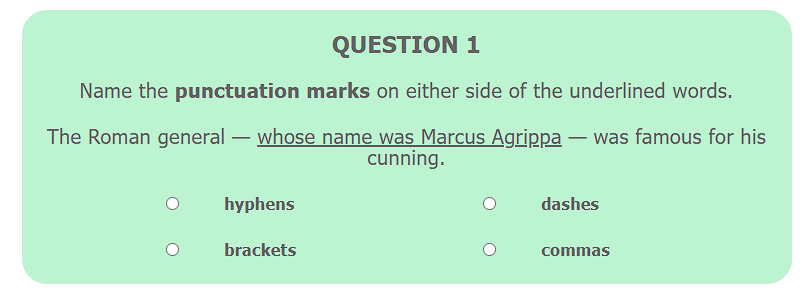

Make sure Year 6 pupils are prepared for SATs with Plazoom’s KS2 SATs Support collection. It contains reading test practice packs and ten SPaG practice papers. It also contains writing evidence activities and fun ‘Revision Blasters’ that are linked to content domains for grammar.

Each Revision Blaster grammar pack includes a recap section for reteaching and a practise section with SATS style questions. They’re perfect for SPaG revision in Year 6.

SPAG practice papers

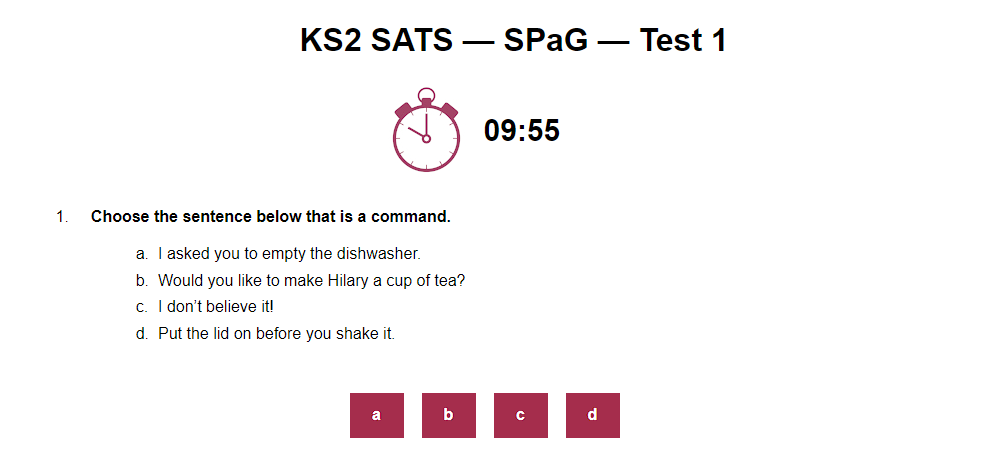

These ten practice SPaG papers from Plazoom feature 12 questions which follow the same format as paper 1 of the English grammar, punctuation and spelling test. All content domains are covered across the collection at least twice.

Inference practice questions

Use these free worksheets from Comprehension Ninja: Inference and Beyond for Upper KS2 to hone your pupils’ inference skills across all the SATs question formats. The questions refer to a fun extract from Oh Maya Gods! by Maz Evans.

SPaG practice papers

These free grammar, punctuation and spelling practice test papers from STP Books are modelled on actual SATs exams. They come with complete answers and marking guidelines.

Year 6 SATs spelling practice

If you want to focus on helping children learn and master spelling patterns, rules and exceptions, visit the Get Spelling Sorted collection on Plazoom. It’s a great repository of revision games and activities.

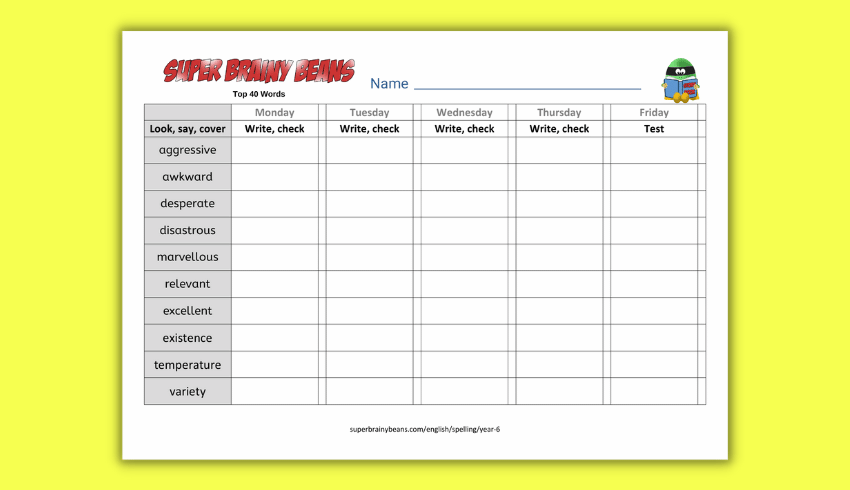

Use this free top 40 words spelling sheet download in Year 6 to practise these common and sometimes tricky words.

Browse more Year 5 and 6 spelling list resources.

Year 6 SATs writing evidence

If you need to gather more independent writing examples to assess Year 6 pupils against the writing Teacher Assessment Framework, use these Year 6 SATs Writing Evidence packs from Plazoom. They’re specially designed to get children producing authentic, independent writing.

Each set of activities is linked to foundation subjects, providing opportunities for cross-curricular writing. For example, write a:

- non-chronological report about bridges

- persuasive report about keeping healthy

- diary recount of an historical event

Year 6 SATs comprehension

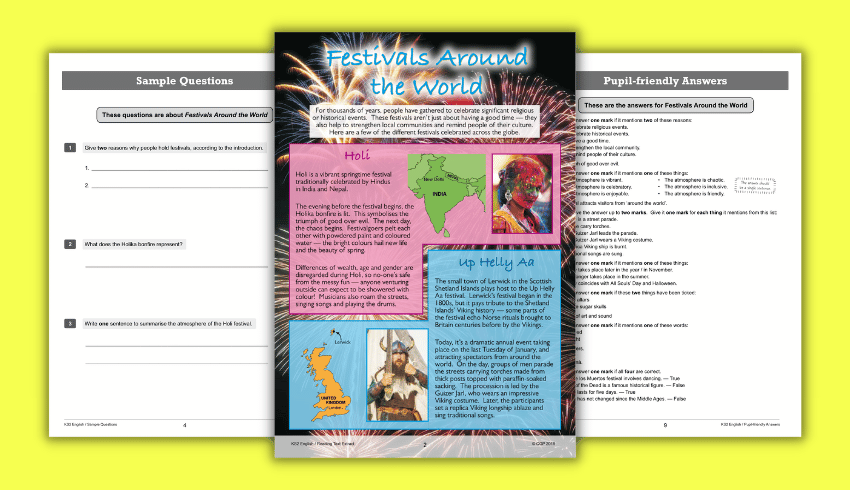

This free sample practice paper from CGP contains a reading text extract, questions and pupil-friendly answers.

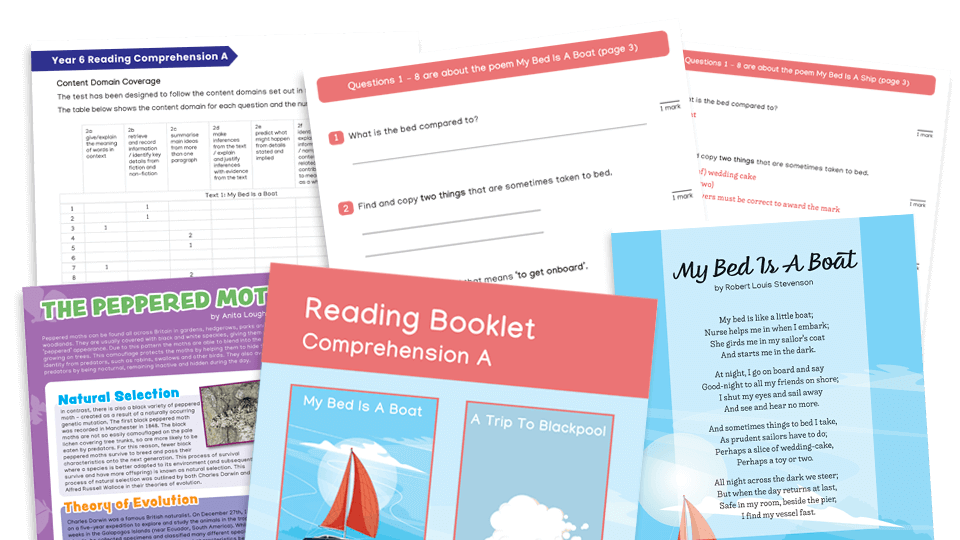

If you’re looking for more Year 6 SATs reading comprehension practice PDFs, try these options from Plazoom.

Each of the three packs has been carefully designed to follow a similar format to the SATs. This means your pupils can become more familiar with their layout and improve their confidence.

Use them as practice tests or use them as part of group or whole-class reading sessions. You could also use them as smaller comprehension activities where pupils read the text and complete the questions.

Choose from Set A, Set B or Set C.

Reading paper revision tips

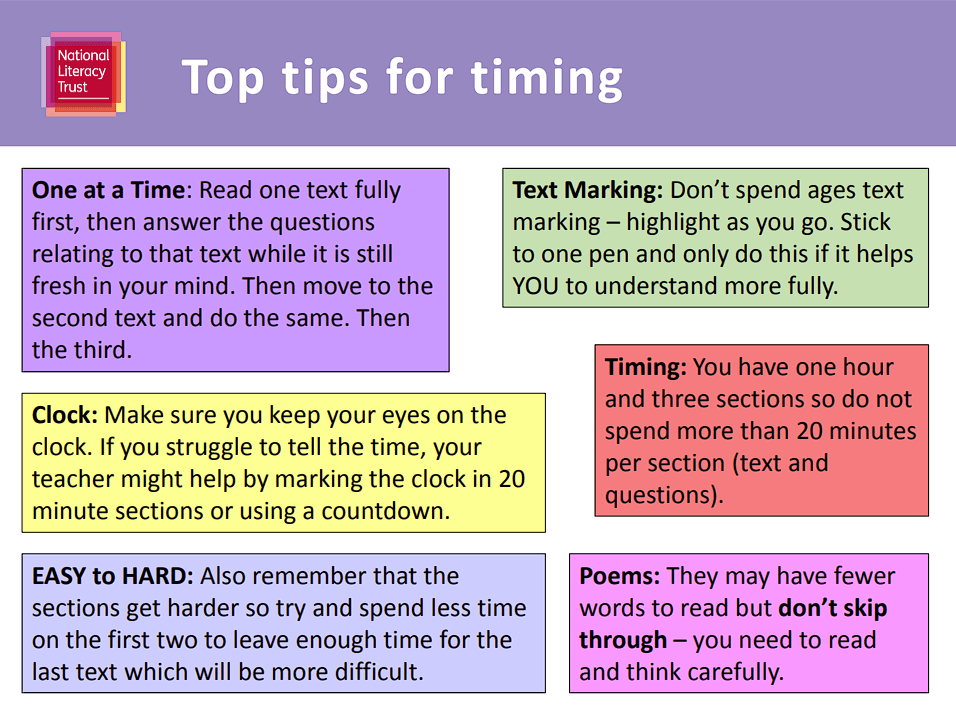

Use this revision guide PowerPoint from the National Literacy Trust to remind pupils of the key aspects of the reading paper before the big day.

English SATs preparation Year 6 advice

Make sure children get the scores they deserve with these last-minute and not-so-last-minute SATS checks from Shareen Wilkinson.

More English SATs preparation ideas

1. Tackling tough words

Teaching vocabulary skills in context is essential. Whilst we cannot predict the words that will appear on the test, we can give pupils quick strategies that will support them, whatever they encounter.

For example, take a classical text and replace certain words with nonsense words. Can the children think of plausible substitutions for your replacements? (I sometimes add capital letters to nonsense words to indicate they might be proper nouns.)

Pupils should be able to deduce what each word might be from the context.

2. Speed searches

Maintain a focus on scanning skills under timed conditions. Quick-fire activities, such as Where’s Wally or spot the difference, are perfect for continuing to develop retrieval skills before they are applied to more complex texts.

3. It’s not what ‘you’ think

It is crucial for pupils to recognise that all answers will be based on the test and not their own views.

Questions that contain the word ‘you’ are somewhat misleading. For example, ‘How can you tell…?’ ‘Give two impressions this gives you.’ Reinforce that evidence is found in the text.

4. Don’t repeat the question

This might seem like an obvious point, but it is crucial that pupils do not repeat the question stem in their answer – but rather explain it.

For example, if the question is ‘Why were the dodos curious and unafraid?’, it’s not unusual in instances like this for children to write something along the lines of, “Because they were unafraid”. This means they’ll miss out on a mark.

To avoid this, work on using synonyms and explaining answers.

5. Perfect punctuation

Accuracy is extremely important. The punctuation of direct speech will only be creditworthy if the closing punctuation is placed inside the final inverted commas.

In previous tests pupils have lost marks for inconsistencies such as mixed use of inverted commas (eg ‘ and “).

6. Read questions closely

‘Write a sentence using the word ‘point’ as a verb. Do not change the word.’

In questions like this, make sure children follow the instruction closely.

Pupils have lost marks in the past for adding a suffix (eg ‘pointed’ or ‘pointing’). They also lost marks for not starting with a capital letter and ending with appropriate punctuation.

7. Watch for stray capitals

If pupils are asked to write a sentence containing an adverb they may be penalised if they spell the adverb incorrectly or if they start the adverb with a capital letter in the middle of a sentence.

Don’t let your pupils miss out due to simple errors.

8. Avoid getting caught out

Prefixes, suffixes, verb forms and plurals must be spelt correctly.

One question in the 2016 grammar paper required pupils to change the word ‘caught’ to the present tense. The answer is ‘catch’, but even though pupils knew the answer, they lost marks for spelling ‘catch’ incorrectly.

Again, spelling does count within the grammar test – even though there is a separate spelling paper.

KS2 maths SATs resources and advice

The KS2 maths SATs test is split into the three papers – and it’s not easy to predict which topics will come up in each one.

Area and perimeter won’t show up in paper 1 (arithmetic) as this is purely a calculation paper. On paper 1, fractions questions will always involve fractions of amounts or multiplying or dividing fractions.

Papers 2 and 3 usually have questions in context. Measures, statistics and shape and space will only come up on these papers.

You can view a list of what can potentially be included in the papers on a government document called Mathematics Test Framework. This lists all the areas that could be tested – but they aren’t all included every year.

What past SATs data tells us

In this webinar from Third Space Learning, two former teachers share the highest impact SATs topics of 2025 using seven years of SATs papers and data from thousands of SATs revision sessions.

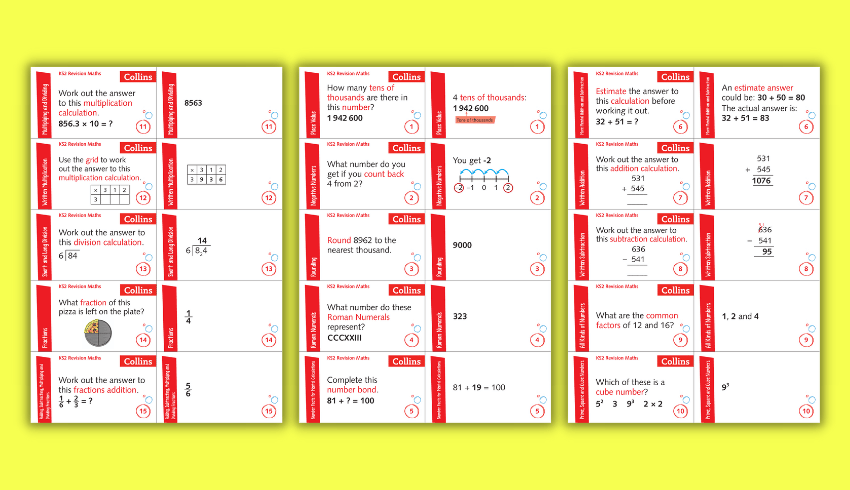

Maths flash cards

This free set of KS2 maths flashcards, created by Collins, will give Year 6 pupils lots of maths practice.

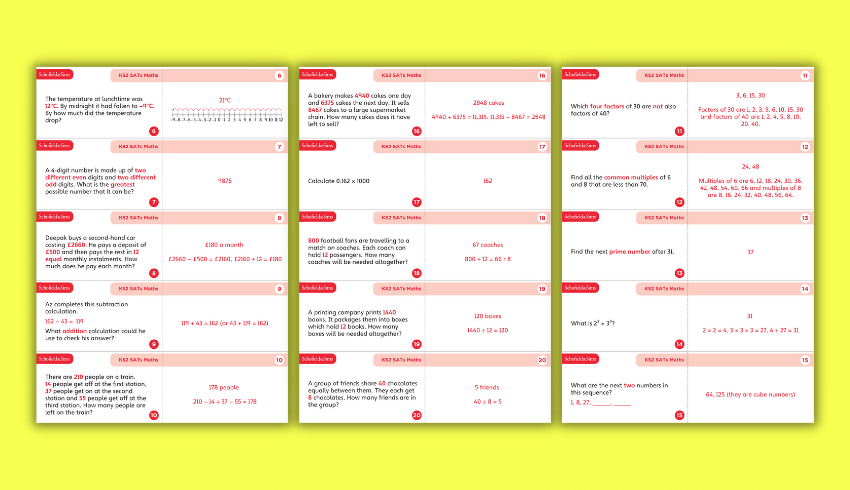

Maths SATs questions

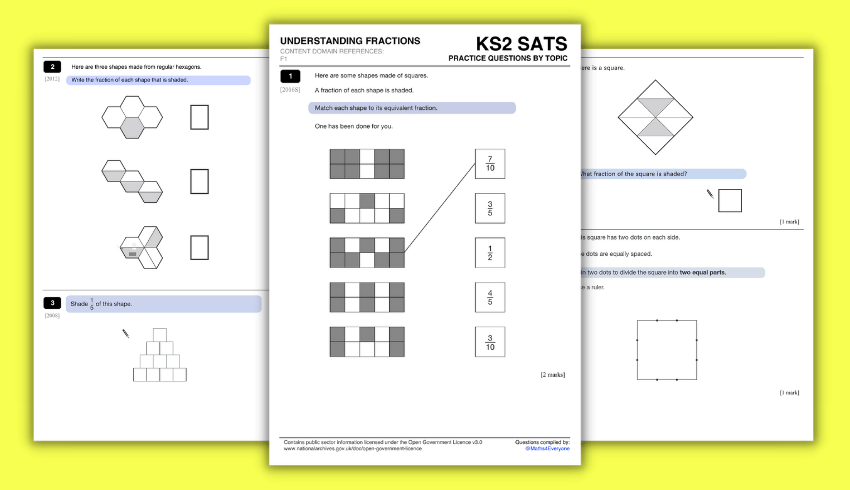

Fractions SATs questions

Using these free fractions SAT questions from experienced maths teacher David Morse will help to test and extend students’ understanding, as well as helping them to prepare for SATs.

You can print the eight-page PDF and turn it into an A4 or A5 booklet. You can also display the solutions on your whiteboard, making feedback more efficient.

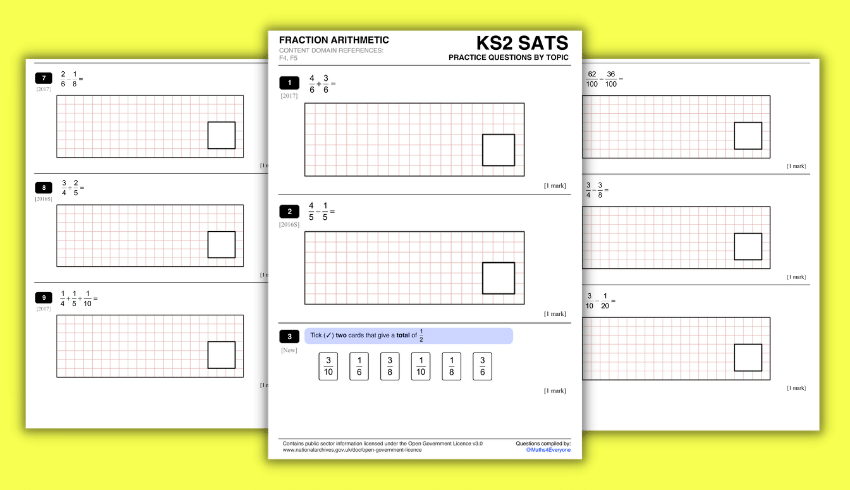

Fraction arithmetic questions

David Morse has also created this free fraction arithmetic questions pack for KS2 SATs practice. It’s a 12-page PDF featuring 32 questions for pupils to have a go at.

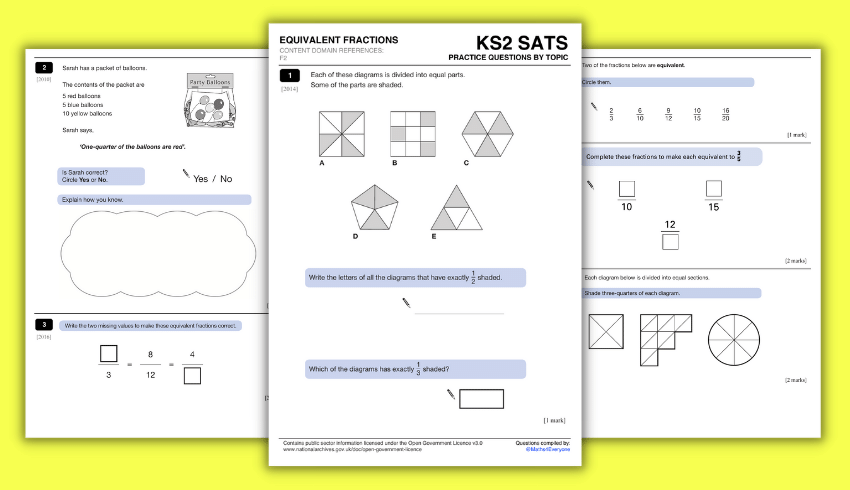

Equivalent fractions Year 6 questions

These free printable equivalent fractions Year 6 questions have fully-worked solutions which can be displayed on a whiteboard.

More KS2 maths worksheets

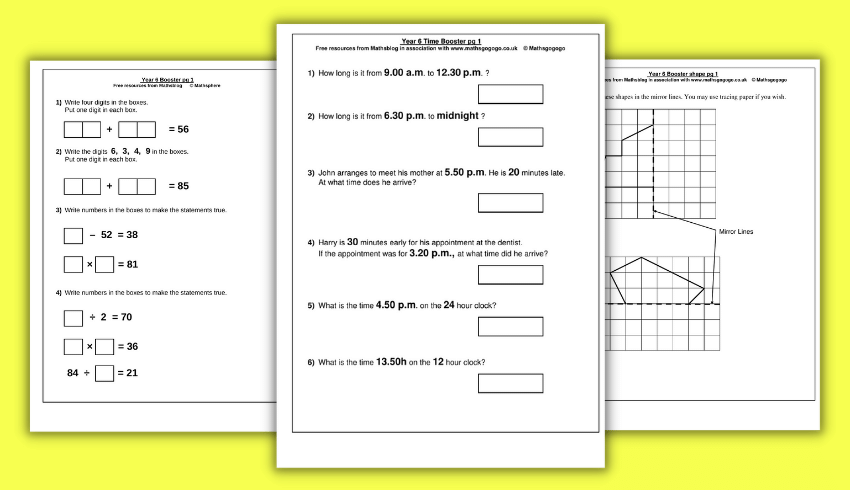

Maths Blog has a whole host of printable KS2 maths booster worksheets that pupils can do at school or at home. There are 14 PDFs for number-related questions, three for shape and four each for time and graphs.

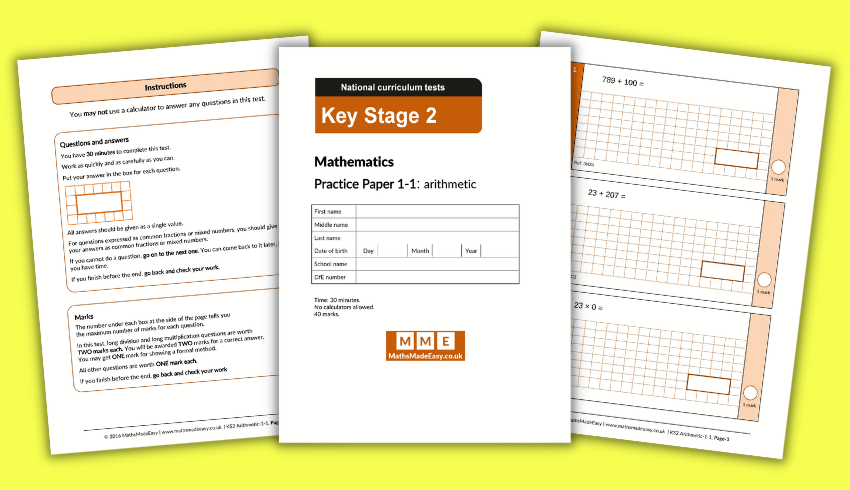

Head over to Maths Made Easy to find more KS2 SATs practice papers. There’s two for arithmetic and four for reasoning to try.

Free KS2 SATs online 10-minute tests

These CGP 10-Minute Tests are ideal for SATs revision in Year 6. There are six tests to choose from – three for maths and three for English.

All the answers are explained at the end of each test, so it’s easy to spot any areas that need a little extra work.

If you’re looking for an offline solution, these SATs 10-Minute Tests downloads from Schofield and Sims cover maths and English for both KS1 and KS2.

Here’s another couple of free online 10-minute tests to try, from STP Books. There’s one focusing on KS2 grammar and punctuation and another on KS2 spelling.

Data-informed SATs prep strategies for 2026

To make sure you’re as ready as possible for end-of-term assessments, use the information at your disposal to guide your revision strategies, advises Richard Selfridge…

Begin by taking a good look at your pupils’ Key Stage 2 experience so far. Use a rough filter to group pupils into two groups:

- those on track to meeting and exceeding expectations. This is likely to be those who have generally been in school, in class, focused on learning and maintaining pace with year group expectations

- those who are likely to need more of your team’s focus in the next few months

Always remember that across the country, most pupils do well in the end of Key Stage 2 assessments. Most of your pupils will too, so keep doing what your school has been doing to help the children get the most out of their final few months of primary school.

Whole-class sessions

Focus on supporting those pupils who have not found learning as straightforward, and who will need closer support in Year 6.

Where possible, aim to do this in class, making changes to your timetable and curriculum focus to plan whole-class sessions, remembering that time spent reviewing learning, filling gaps and managing misunderstandings is likely to benefit every child.

For example, where you have identified a weakness in calculation strategies for your focus children, use part of your morning sessions twice a week to dedicate 10 to 15 minutes to reviewing and developing calculation strategies.

This may be in a section of the morning when you usually review or recap general learning, or you may timetable this activity as part of two specific maths lessons.

Maths prep

The 2025 results showed 75 per cent of pupils meeting expected standard in maths, with 26 per cent achieving higher standard.

DfE analysis reveals persistent challenges in reasoning, problem-solving and applying knowledge to unfamiliar contexts.

Fractions, ratio, proportion

Use assessment data to identify specific domains where your cohort struggles. If they are like most children across the country, this is likely to be fractions, ratio and proportion, and multi-step problems.

Create a revision timetable using spaced repetition, revisiting challenging topics multiple times rather than leaving difficult areas until the final weeks.

Arithmetic fluency remains fundamental, as does effective use of calculation methods. A few minutes of daily practice builds automaticity.

For reasoning, teach pupils to dissect word problems methodically, modelling how to identify key information and determine which operations are needed. This metacognitive approach helps embed understanding, rather than relying on learned procedures.

Reading prep

Reading held up well in 2025, with 74 per cent of pupils meeting the expected standard. However, comprehension remains challenging, particularly with inference, retrieval from dense texts and vocabulary questions.

Create focused mini-lessons using a clear Objective/Model/Practise/ Review structure, for example, addressing specific weaknesses identified through your ongoing formative assessment, rather than simply repeating comprehensions.

Build stamina for the test format – pupils face one hour with substantial booklets, requiring concentration and time-management skills.

Continue daily class reading of rich, challenging texts throughout the spring term. Exposure to sophisticated vocabulary and complex sentences supports comprehension far more effectively than isolated test practice.

Explicitly teach how to approach different question types: skimming for key words in retrieval questions, combining textual clues with prior knowledge for inference, and using context and word parts for vocabulary questions.

GPS prep

Grammar, punctuation and spelling results remained steady at 74 per cent of pupils meeting expected standard in 2025.

This test is particularly suited to targeted preparation, as the content domain is clearly defined and pupils can make rapid progress with focused teaching.

Use item-level analysis – where you consider how pupils answer the different types of questions in GPS assessments – to identify precisely which grammar concepts your pupils haven’t mastered.

Clauses, subjuctive mood, complex sentences

Common stumbling blocks include identifying clauses, using the subjunctive mood and applying punctuation in complex sentences.

For spelling, analyse patterns in errors. Are pupils making mistakes with high frequency words, commonly misspelled words or prefixes and suffixes, for example?

Target teaching towards these patterns using morphological approaches. Short, daily practice is usually more effective than longer weekly sessions.

Writing prep

Writing teacher assessment showed 72 per cent of children meeting expected standard in 2025, but just 13 per cent worked at greater depth, unchanged since 2022.

This suggests many pupils achieve expected standard but struggle to demonstrate the sophistication required for higher outcomes.

Provide regular extended writing opportunities where pupils draft, refine and edit substantial pieces. Model the writing process explicitly, showing how to plan effectively and make ambitious vocabulary choices.

Focus on addressing pupils’ specific weaknesses. For example, some need handwriting fluency; others need spelling and punctuation support; some need help generating ideas.

Once again, build this into your working week using the periods at the beginning and end of the school day, for example, or times before and after breaks.

SATs week prep

As SATs week approaches, transition to consolidation and confidence-building. In the final fortnight, you are likely to be more nervous than most of your pupils; try not to let this show! Make sure that you are familiar with requirements for the assessment days themselves (read the DfE’s guidance) and that your pupils know what is expected of them during SATs week.

Make sure, too, that you have a clear plan for timetable arrangements, breakfast provision, additional staffing for access arrangements, and room prep, and involve all the staff in your briefings. And don’t forget to celebrate the end of SATs week!

Richard Selfridge is a primary teacher, writer and Insight Education data consultant. He is the author of A Little Guide for Teachers to Using Student Data (SAGE).

How to stop SATs prep taking over

Preparing for SATs doesn’t need to take over the whole of Year 6, says KS2 teacher Sarah Farrell. Dipping in little and often is much easier to digest…

While we don’t want SATs to dominate our children’s last year of school, we do want them to feel prepared and to be as successful as they can.

While it can be tempting to restrict a Year 6 timetable to be as SATs-focused as possible over the next few weeks, there are better ways to make sure both you and your class feel ready by the time May comes around.

And remember: SATs are a whole-school responsibility. The tests cover content from the whole of Key Stage 2, so it is not solely down to you to get the children to achieve 100 per cent.

Practise

Rather than packing your timetable with lots of extra full-length maths and reading lessons, consider shorter, sharper sessions.

A ten-minute speed-reading practice or quick refresh on multiplying pairs of fractions is likely to be more effective than replacing an afternoon of wider curriculum lessons.

You could also include activities such as online quizzes and games to keep it interesting and avoid too much repetitive written practice.

Target

Identify any whole-class, group or individual areas of weakness that your class may have and build in time to directly target them.

If the majority of the class finds it tricky to calculate a fraction of an amount, for example, make that a part of the beginning of every maths lesson for a week.

For small group or individual areas, providing some targeted questions as morning work can close gaps and help children to feel more confident.

Model

Modelling how to approach the papers is a great way to show children what to expect and how to avoid common pitfalls.

For example, you might display a question from the reading test and model your thinking aloud like this:

“The question says that I need to look at paragraph four, so I’m going to find paragraph four first of all. It then asks me to identify how Ben knew there was a dolphin nearby before he could see it, so I’m looking for clues in the text that might relate to his other senses or maybe to the water rippling.

“I’m then going to check that the evidence I’ve found is definitely in paragraph four, as that’s where I was told to look. “It’s asked me for two examples, so I’m going to make sure I write two pieces of evidence down.”

While this may seem like a lot, explaining your thinking helps children know how to approach similar questions.

With maths questions, model underlining key information, drawing bar models or diagrams, or writing out the steps you’ll take when answering a reasoning question.

Discuss

When presented with a wordy problem with several large numbers, some children may panic and not try it at all, or just add all the numbers together and hope for the best.

A great way to recap key facts and help children to develop their ability to answer tricky questions is to initially hide key information.

For example, display a multi-step reasoning problem with the numbers covered. Ask children to discuss in pairs how they might approach the question, then share strategies together.

As a class, agree on a set of steps that will be completed when the numbers are shown. When you have a plan, share the numbers and set the class off to complete the question.

The benefit of this approach is that it slows children down a bit and encourages them to really think about what’s being asked in order to help them to select the right operations needed.

Find

Children love finding mistakes! Present them with some questions that you have completed badly and task the children with finding out what mistakes you have made.

Try to use mistakes that your class commonly make themselves, as this is a great way to tackle persistent errors. You could then create a class list of common mistakes to prevent them from making them again when they next come to take a test.

Sarah Farrell is a KS2 teacher in Bristol who makes and shares resources online.