Empathy Day 2025 – Best activities, books and curriculum ideas

Celebrate Empathy Day this June with these brilliant resources and ideas from fellow teachers…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Want to celebrate Empathy Day 2025 in your school but not sure where to start? We’ve got you covered!

(These resources are also great for Empathy Week, next taking place in March 2026).

Table of contents

What is Empathy Day?

Research tells us that 1 in 16 10-15-year-olds are not happy with their lives. Teachers are reporting rising levels of anxiety and mental health problems.

The Empathy Day Festival aims to celebrate empathy’s power to build a kinder, less divided world. It was founded in 2017 and aims to drive a new empathy movement and remind everyone that empathy is a skill that can be learnt.

Empathy Day is story-driven, inspired by scientific evidence that in identifying with book characters, we learn to see things from other points of view. The day is organised by social enterprise, EmpathyLab.

There are lots of free resources available to help you make the most of the Empathy Day Festival in your setting. Register now. You can also sign up for a free webinar on getting the most out of the festival.

It’s completely up to you how much you take part in – you can do just Empathy Day, a few afternoons across the festival, or join in every day.

When is Empathy Day 2025?

Empathy Day Festival runs from 2nd-12th June, culminating in Empathy Day on 12th June.

Empathy Day resources

Kindness lesson plan

This free lesson plan for KS1 and KS2 is perfect for Empathy Day. It investigates how children can connect to both their peers and their community in fulfilling and meaningful ways. It also touches on connecting with yourself to overcome life’s challenges.

The lesson explores how to use nature to improve connections, what a growth mindset is and how to use positive self-talk. Pupils will also learn about the importance of kindness and how to put it into action.

Communication lesson plan

Help your class build empathy and understanding with this free communication lesson plan from Emily Azouelos, which teaches children how to listen actively, recognise verbal and non-verbal cues, and respond thoughtfully during conflict.

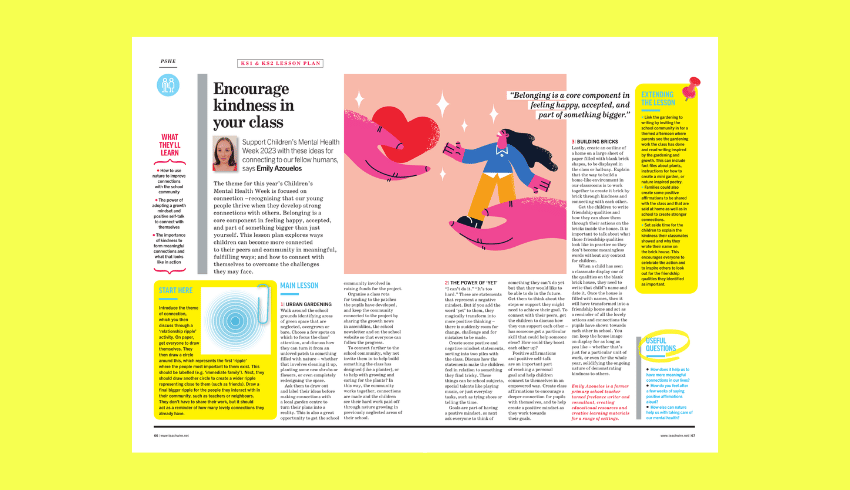

Drama resources for Empathy Day

Starting a task with a drama activity can be a powerful way to engage pupils, encouraging them to explore different perspectives by stepping into the shoes of various characters. Use these free worksheets from literacy resources website Plazoom to help you get started:

Role on the Wall: Choose a character and record information about them on the inside of the template. On the outside, record information you have inferred about them from things that you have read or seen.

Conscience Alley: Record information about a dilemma a character is facing and how they may be feeling, then make a decision about what the character might do next.

Hot Seating: Explore a character and what their responses during a hot seating activity might be. This worksheet also helps pupils formulate relevant questions to ask the person in character.

Official Empathy Day resources

Empathy Day Festival 2025

EmpathyLab’s work is built on scientific research which shows that empathy is a skill, not a character trait. We can all develop this skill at any point in our lives.

In fact, only 10% of our empathy is genetic. The rest comes from societal and environmental factors. This means that explicitly teaching empathy, during formal and informal learning, is absolutely vital in developing this key social and emotional skill.

Here are some of the official Empathy Day Festival resources on offer this year:

- Empathy Day assembly with Children’s Laureate, Frank Cottrell-Boyce – available on demand.

- Empathy Challenge – nine fun and creative activities to connect reading and empathy.

- Daily events with top authors and illustrators to watch on demand.

- Live author events including Elle McNicoll and Joseph Coelho for empathy inspiration – some are also available in Welsh. Register here.

- Toolkits full of ideas, plus all the digital and printable resources you need.

- Interactive map – so you can promote your event and find out what’s happening locally

See the full Empathy Day Festival programme.

Empathy Day training

EmpathyLab runs year-round training. Explore the latest expert short training courses.

There are also three professional development webinars for adults with partner organisations including Auticon, Place2Be and World Book Day. These are suitable for library staff, teachers and parents.

The Island by Armin Greder

The Island by Armin Greder, is a powerful picture book for older learners that tackles issues of prejudice and discrimination head-on. The story provides a potent means of exploring the importance of compassion.

Download our free sequence of lessons and accompanying PowerPoint to help children explore prejudice and create their own compassionate journalistic writing.

Rose Meets Mr Wintergarten

In the deceptively simple picture book Rose Meets Mr Wintergarten, we see how a single act of kindness changes the life of an insular, isolated old man, and benefits the entire neighbourhood. This free PDF features a range of cross-curricular KS1 activities, all based around this charming title.

The Boy at the Back of the Class

This free PDF of activity ideas will explain how to use modern classic The Boy at the Back of the Class to promote empathy and compassion in your KS2 classroom.

Empathy Day handbook

This empathy handbook for 7-12-year-olds celebrates Empathy Day. Written by Rashmi Sirdeshpande, We’ve Got This! takes readers through six simple steps to harness empathy as their human superpower.

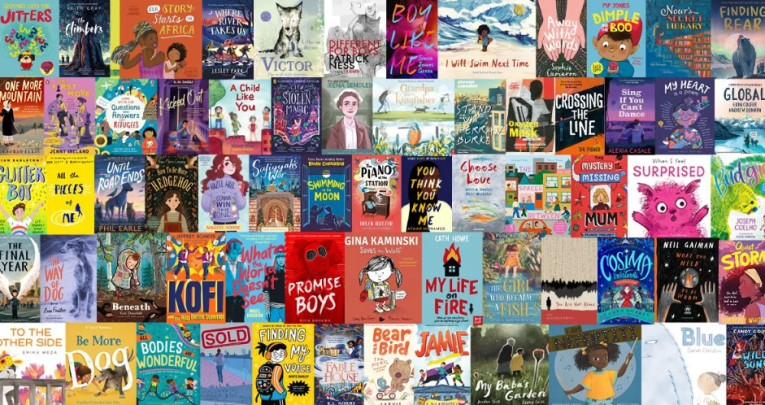

#ReadForEmpathy collection

The Read for Empathy collection is a list of 70 expertly selected books for children and young people aged 3-16. These powerful recommendations, including The Grand Hotel of Feelings and The Boy in the Suit, are excellent to use at the heart of your activity.

KS4 empathy and bullying lesson plan

By the time they reach KS4, pupils will have revisited bullying many times over their school career. It can be hard to make it feel relevant. After all, none of them are bullies. Are they?

This lesson seeks to push students to realise that bullying can sometimes happen thoughtlessly. Standing by or turning a blind eye allows a culture where bullying is covertly accepted to thrive.

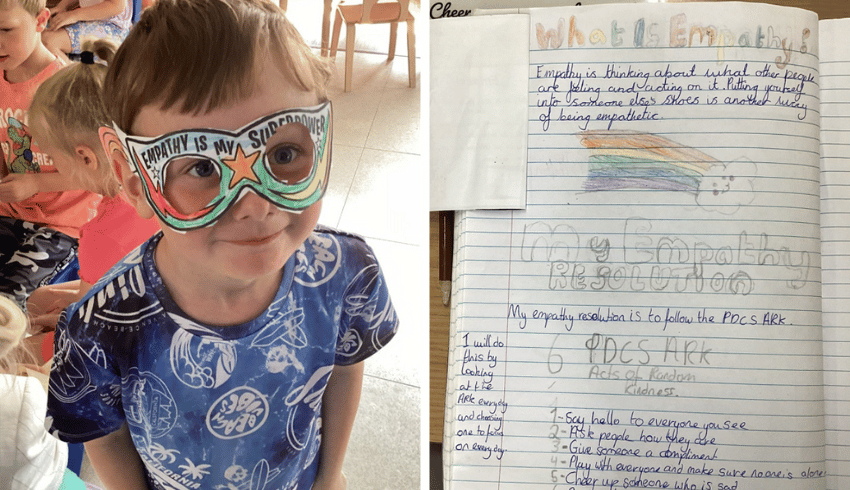

Empathy Day case study: Pembroke Dock Community School

Year 1 teacher Kate Clarke explains what her school does for Empathy Day, and the lasting effect it has had on her pupils…

Every year we take part in Empathy Day. It’s a great opportunity to come off-timetable for the day and have a whole day focused on empathy texts.

This year, as in previous years, we are looking forward to watching the videos created by authors describing their empathy resolutions and carrying out many of the Mission Empathy challenges themselves to model them for our pupils.

We always make empathy resolutions on Empathy Day. I find this a really powerful part of the day. It’s about putting empathy into action. Our pupils really think what they can do to make a difference.

I loved one of the resolutions where a pupil said that she needed to challenge herself to see other people’s points of view.

Our older pupils enjoy reading the Empathy Shorts in the run-up to Empathy Day. These are fantastic collections designed to make sure that every child has access to an empathy-boosting story.

Each story in the collection gives a unique take on seeing life from another’s perspective. Pupils enjoy reading them on their own, with friends or as a class.

There’s always lots of discussion after reading these as they’re really powerful and thought-provoking.

Empathy Day celebrates and grows empathy’s power to create a better world. It really shines a light on the role books play in raising an empathy-educated generation.

More empathy activity ideas

Painting pebbles

As a class we read The Invisible by Tom Percival. It’s a story about a little girl who is ignored in her community as she lives in poverty, to the point where she feels like she disappears.

She notices others who are invisible too and seeks to help them. The community joins together and everyone helps each other out and they are no longer invisible.

We went for an empathy walk in our community, drew empathy maps and attributed feelings to each part of our walk.

Pupils felt sad when they saw people sitting on their own in the park. When we got back to school we decided to collect pebbles and paint them then hide them in the park to cheer up whoever found them.

We encouraged pebble finders to share their photos on social media and had some lovely kind responses from people in our community who said our pebbles brought sunshine to their day.

Food bank visitors

We also explored It’s a No-Money Day by Kate Milner. It’s about a young girl and her mum who live in poverty and have to visit a food bank.

We invited staff from our local foodbank to explain who visits them. Our pupils decided they wanted to help people in our community by setting up trollies in our school where pupils and members of the community could come in and help themselves to whatever they needed.

We gained support from local businesses and filled trollies for every class in the school with items such as fruit, sanitary products, hats, gloves, sun cream and hairbrushes.

Pupils can help themselves to what they need, and items are replenished daily. We have also set up a ‘help yourself hub’ where members of our community can come and take clothing, nappies, toiletries and washing powder. This heartwarming idea from our youngest pupils has helped countless families in need.

Lasting effects of Empathy Day

Our pupils have developed their empathic listening and communication skills. They are able to go beyond simply hearing what someone is saying and can reflect and respond in a way that shows genuine understanding and care.

This, in turn, has had a positive impact on pupil wellbeing, creating a safer school culture and fostering positive pupil relationships.

5 books to encourage empathy, plus activities

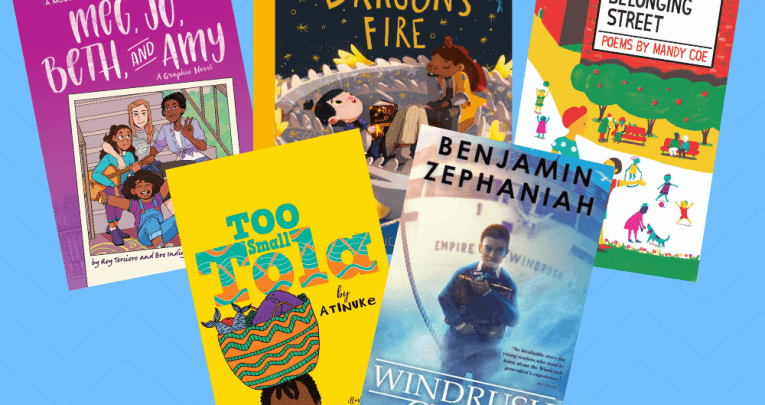

Once Upon a Dragon’s Fire by Beatrice Blue (Frances Lincoln)

What’s the story?

Rumours abound about a fearsome dragon and the village is terrified of him. But it takes two children with open hearts and minds to visit the dragon and recognise what he needs to combat his sorrow and loneliness. And the warmth the dragon feels when someone starts to care helps save the village from a terrible storm.

This is a gorgeous picture book about understanding others and the empathetic power of stories.

Try this…

- Discuss how rumours can cause terrible harm. Talk about how misunderstandings can spread.

- Characters Sylas and Freya instinctively know how to comfort the lonely dragon. He needs lots of stories. Make a big dragon and create a ‘dragon story shelf’ in the classroom. Everyone can choose books for the shelf that they would like to read to the dragon.

- Freya and Sylas are also very sensitive to the needs of the dragon. They want to share stories that don’t hurt his feelings, so they make up their own. Write your own stories for a dragon and create a story book.

- In the story, the children’s empathy is strengthened by meeting the dragon. They need to help the villagers to understand the dragon too. Imagine you are Freya or Sylas and create a magazine or podcast all about the dragon that you could share with the village.

Too Small Tola by Atinuke, illustrated by Onyinye Iwu (Walker Books)

What’s the story?

Tola is the smallest member of the family. Her siblings often doubt her abilitie. However, ever surprising, Tola demonstrates that being small need not hold anyone back.

This book is great for expanding children’s world views, with insights into Tola’s Nigerian life, in which people with different religious beliefs live together. It will also help children recognise some of the universal themes and challenges of childhood – a fantastic early reader.

Try this…

- Step into Tola’s shoes. What would it feel like to be Tola, always being told you’re too small? Discuss in pairs then write emotion words on the board.

- Tola and her siblings must fetch all the water they need for the day before they go to school. Water is precious. In groups, imagine you are a member of Tola’s family and plan how to use the water carefully for the day ahead to ensure it doesn’t run out. How do pupils feel about some people having water on tap and others having to queue for it every day?

- Explore the beautiful Nigerian fabrics that Mr Abdul uses to make clothes. Ask children to copy their favourite design onto a piece of paper or design their own.

- The residents of Tola’s apartment celebrate Easter and Ramadan. Research these festivals, share experiences and present findings to classmates.

Windrush Child by Benjamin Zephaniah (Scholastic)

What’s the story?

Leonard has an idyllic childhood in Jamaica. However, at the age of ten he boards a ship with his mother to journey to England. Once there, he’s reunited with his father who has already been working in England for several years.

Leonard and his parents are part of the Windrush generation. As well as getting used to the cold weather and cramped living conditions, Leonard has to deal with daily prejudice and racism. The story follows Leonard up until 2018, when he is denied citizenship by the country that is his home.

Try this…

- Imagine you are Leonard leaving home in order to live in another country. List three things that you would look forward to and three things you would worry about.

- Listen to the poem Windrush by Denniston Stewart. Discuss how the experiences of the narrator compare to the experiences of Leonard and his family.

- What would happen if Leonard joined your school? How would the class make him feel welcome? What would you want him to know about life at your school? What advice would you give him to help him settle in?

- Listen to the Benjamin Zephaniah episode of the Author in your Classroom podcast to hear the late author talking about this book and his writing process.

Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy by Bre Indigo and Rey Terciero (Little, Brown Young Readers US)

What’s the story?

This graphic novel reimagines the story of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women and shifts its location to modern-day Brooklyn. With their father away at war, it’s up to the March sisters to occupy themselves while their mother works to make ends meet.

Letters and emails from each of the girls split up the chapters and provide insight into each character’s world.

With sensitive portrayals of illness, blended families, sexuality, class, and race, the text shines a light on a range of experiences, prompting readers to question what it might feel like to be in the characters’ position and reflect on their own lives.

Try this…

- Which March sister do you most relate to? Write a diary extract about one of your favourite scenes in the book from their perspective. What might they be thinking?

- One of the central themes of the text is family. People live in lots of different types of families. Can you illustrate your family or the people you live with in a similar style? How could you represent everyone’s personality, hobbies and interests? How does your family compare to that of the March family?

- The text touches on some complex themes, ending with the girls at a Women’s March. Explore one of the more complex issues depicted in the graphic novel. Use websites such as CBBC’s Newsround to provide a child-friendly view of current affairs.

Belonging Street by Mandy Coe (Otter-Barry Books)

What’s the story?

Belonging Street is a wide-ranging collection of poems, all based on a loose theme of belonging. Poet and illustrator Mandy Coe has written about the natural world and why we are responsible for protecting it, the importance of family life and the power of connection.

The poems create wonderful discussion opportunities, as well as chances for students to write and be creative, and encourage empathy with our planet and its inhabitants.

Try this…

- Read the poem Coming Home To You. Discuss what ‘home’ means. Does it mean the same to everyone? If you had to summarise home in five words, what would they be?

- Explore the poem Hearing The Earth, Feeling The Earth. In groups discuss how you can help to care for the planet. Make posters for the classroom showing why it’s important to look after the world and what people can do to help.

- Find out what your school is already doing to protect the environment and if there is more that can be done. Present ideas to the headteacher or school council.

- Read and discuss the poem Take The Leap. Ask children to think about a time they did something that scared them. How did they feel before, during and after? What would they say to friends who are feeling scared? Can being scared sometimes be a good thing?

Thank you to contributors Jon Biddle (Moorlands Primary Academy), Richard Charlesworth (Springwell School) and Sarah Mears (EmpathyLab co-founder).

More Empathy Day ideas

Primary teachers and Empathy Book Collection selection panel judges Jon Biddle and Richard Charlesworth explain how to embed empathy throughout your school…

We all know how squeezed the primary curriculum is (and it’s getting more squeezed every year) but helping children develop the ability to empathise is something that we can’t ignore.

Some subjects – such as English and history – are a natural fit, but others require a little more thinking. However, there are stories to be told in all subjects, and we will be using these as the basis for much of our work on Empathy Day.

Maths

In maths we occasionally learn about mathematicians who have been overlooked in history. For example, Muhammad al-Khwarizmi isn’t a name that most of us know, but his work helped ensure that modern arithmetic is based around just ten different digits.

How might he feel to know that his work had such a lasting impact? Would you be proud to learn that something you had done was still being used over a thousand years later? What might you say to someone who wasn’t happy with their work?

A short conversation about these ideas while teaching place value can give the lesson an empathy focus without taking away from its main objectives.

A fan of algorithms, strings and Booleans? Or want to find out what each of those are? Then you might like to explore empathy alongside computing.

Texts such as Aimee Lucido’s verse novel In the Key of Code can link to coding lessons and act as a springboard for children to go on and find out about coding languages themselves.

Presented in poetic forms, with cleverly interwoven references to music, texts like this will link well to the curriculum as well as allowing readers to discuss themes around loneliness and moving homes.

PSHE

Encouraging empathy and developing pupils’ awareness of current affairs can be a challenging task. Using authentic and autobiographical texts, such as Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed’s When Stars are Scattered can be a great way to not only link to areas of the PHSE curriculum, but wider societal issues, such as human rights and the refugee experience.

Pupils could explore individual spreads in the graphic novel to discuss the emotions of each character and their actions. Alternatively, the text could prompt greater action, with classes exploring who the decision makers are in their local community – linking empathy to power.

Combining texts with further research (such as focusing on the work of charities including the British Red Cross, and the UN Refugee Agency) can enrich experiences in the classroom and connect ‘human crisis’ with ‘human kindness’.

Humanities

Exploring history with an empathetic perspective can also bring lesser-known narratives and historical figures to the fore.

Trending

Using well-researched texts such as Black and British: An illustrated history (David Olusoga, illustrated by Jake Alexander & Melleny Taylor), Mohinder’s War (Bali Rai) and After the War (Tom Palmer), can offer teachers – and readers – a range of viewpoints to analyse periods of history.

Ask children to spend time listening to family members, friends or neighbours and discover more about their lives. Children could share a secret ambition, or learn about their parent/carer’s childhood.

You could also go for an Empathy Walk in the local community. This could work beautifully alongside any unit of work based around the local area.

After returning, the children can discuss what they’ve seen; the effect of litter on the local environment, a couple deep in conversation on a bench, or a parent enjoying time with their young child in the park.

You can even adapt this to create an ‘Empathy Map’ of the local area.

Empathy Resolutions are something that only take a few minutes to write, but the impact can be enormous. Every Empathy Day, across the whole school, we ask our children to write down one way that they will try to be more empathetic in the future.

Previous examples have included not judging people that they don’t know or trying to understand people better when they’re being annoying.

We then share these in a whole-school display and refer to them again during Empathy Reflection Month (November), where we share how well we think we’ve done.

Books

When selecting a class book to read together, the Read for Empathy collection is always full of powerful recommendations.

In 2022 we enjoyed A Street Dog Named Pup by Gill Lewis, The Last Bear by Hannah Gold, Valerie Bloom’s poetry collection Stars with Flaming Tails, and picture books The Invisible by Tom Percival and Nen and the Lonely Fisherman by Ian Eagleton and James Mayhew.

Because the writing in all the books is so rich, with a really clear empathy focus, conversations and discussions while reading evolve almost organically.

The talk is very much based around the characters in the text, how we empathise with them and how we would behave if facing similar situations.

Many of the conversations lead into the children wanting to engage in social action based around themes of the book, which is one of EmpathyLab’s goals.

In The Last Bear, a polar bear is stranded on an island due to climate change. Many pupils went home and talked with their families about climate change and a group of them went to ask the headteacher whether he thought the school was doing enough to reduce its carbon footprint.

This led to making some simple changes, such as introducing light and board monitors in each class. Because the push came from the children, it gave them an extra sense of empowerment and ownership over the situation.

Exploring empathy in English lessons

Diane Lee explains why English classrooms are the perfect venues in which to explore the nature of empathy…

Let me pose a question. It’s one I’m sure you’ve been asked countless times before, but this time, I want you to give me an instant, knee-jerk answer – why did you become a teacher?

If your response was something like, ‘imparting knowledge’, then I respectfully put it to you that Google can do that too. If, however, your answer was along the lines of ‘Educating for life’, or ‘Helping someone realise and fulfil their potential’, then, in my opinion at least, you’re closer to what I believe an educator’s role in a young person’s life should be.

We can assist young people in many different ways beyond academia – by helping them become more emotionally literate, competent and compassionate, for example. Sharing your own gut-wrenching stories of unfairness or injustice and encouraging them to do the same; calling upon, and then tapping their into feelings, emotions and experiences.

In an English classroom, via the discussions you have, the texts you read, the creative writing tasks you set and classroom activities you organise, your lessons can develop children and young people in more ways than you or they might imagine…

Avoid the danger zone

What books are you reading with your class? The same titles as always? It’s understandable – not all schools have the luxury of changing their curriculum, sometimes due to lack of budget or resourcing, and there can be a reluctance to let go of the familiar.

“Your lessons can develop children and young people in more ways than you or they might imagine”

The problem is that familiarity can feel comforting, but will also present you with a danger zone. Teaching the same text year in, year out can dull your senses to the different ways of seeing and teaching its themes, context, plot, events and character nuances. Believe me, I’ve been there – but it is possible to approach every text, even the most well-worn, from a fresh vantage point.

Presenting an old text through a new lens – studying Shakespeare with the aid of modern adaptations, or studying texts critically by looking at characters through an intersectional lens, for example – can give way to a richer learning experience, leaving you and your class with a more compassionate view of the characters and perhaps the text as a whole.

Greater compassion

Conversely, if you’re able to make the switch and select different texts altogether, then go for it! We’re fortunate to be part of the Lit in Colour programme, through which we receive free set texts by writers of colour, allowing us to retire a long-taught GCSE text in favour of a fresh, more relatable story.

We recently chose Refugee Boy – the stage adaptation by Lemn Sissay, based on the novel by Benjamin Zephaniah. In a predominantly white student population school in Suffolk, making this change was not only important to us, but allowed us to introduce our students to a text in which the protagonist has been treated unfairly.

Did our students more readily identify with the unfair treatment portrayed because it resonated and connected with their own experiences? The answer was an emphatic and resounding, ‘Yes!’

“If you’re able to make the switch and select different texts altogether, then go for it”

This change in text has also fostered greater compassion in many other areas. While being taught the context alongside the text, my class watched a powerful video on the refugee experience, and another on ‘What they took with them’ – a televised adaptation of a poem with its lines read by famous actors.

This led to a discussion about what the students had seen, and what they would take with them if they had to leave their home suddenly to flee persecution, conflict or war. From there, we proceeded to an imaginative writing activity in which they wrote about the setting, the possessions they would take with them and why.

I can honestly say that what my Y10s wrote that day well and truly exemplified what’s now expressed in modern parlance as, ‘They understood the assignment.’

Universal similarities

It’s noted in the CLPE’s 2020 ‘Reflecting Realities’ report on ethnic representation within UK children’s literature that, ‘‘As human beings, there are some key universal similarities that bind us, but also key distinctions in our lived experiences. A book can serve as a stimulus for exploring points of difference; providing recognition and affirmation for readers who can identify, and provide invaluable insight for those who may not.”

Walking my students through learning opportunities, actively encouraging them to put themselves in the place of a character they are studying is vital. And yet, not once have I used the word empathy in this article, until now [the header and standfirst intros don’t count, we write those bits – Ed]. Why is that?

It’s because successfully teaching and creating moments that develop students’ empathic skills is about so much more than explicitly stating that that’s what you’re doing.

Theodore Roosevelt once said, “No one will care how much you know until they know how much you care.” As an educator who desires to prepare their students to be global citizens, I’d maintain that you should model the type of caring, compassionate and empathetic behaviours you wish to see in your students.

The empathy baton

As you pass this invisible ‘empathy baton’ on to your students, they will in turn grab it with both hands and proceed to run their own race, as per the path laid out before them. Their run, or their lives, will stretch out far beyond your classroom, and hopefully see them eventually pass that same baton on to those who come afterwards, only for it to be passed on again.

Never forget – you are the curator of your class’s compassion and comprehension, and the empathy barometer of another’s person’s reality and lived experience. To help you perform that role successfully, you’re in the powerful position of being able to invite your students to metaphorically and literally share a table with others who may not look like them, or share similar life experiences. You can do this every time you introduce them to characters who aren’t like them.

True inclusion

True inclusion sees to it that this is a table at which everyone can be seated, since you’re demonstrating that you want each individual to feel as though they’re welcome and that they belong. As one of the characters in the 1993 film Shadowlands puts it, ‘We read to know we are not alone.’ To which I would only add, ‘We are not alone when we truly feel as though we belong.’

“You are the curator of your class’s compassion and comprehension”

We see appeals for equality, diversity and inclusion everywhere – but I put it to you that it isn’t some passing trend, but an urgent challenge which which can produce a great deal of good. As Stormzy once remarked, “I encourage everyone… to not just use diversity as a buzzword –whatever position you’re in, whatever role you play, be a driving factor for it, and [don’t] just see it as a quota, or a box to tick.”

What’s worked for me

- Teach a diverse text that students can connect with and which provides topical content, such as Refugee Boy – or at least examine more traditional texts through a different lens

- Be willing to sit with discomfort, on the understanding that some students may be sitting in discomfort beneath your very gaze

- Have uncomfortable and vulnerable conversations with colleagues about what you know, what you don’t know and what you need to learn

- Commit to meaningful CPD that can help you become more insightful

- If working with children who are forcibly displaced, or children who have experienced trauma, try the ‘Healing Classroom’ approach – a free course of trauma-informed training delivered by the International Rescue Committee

- Keep an eye out for commemoration dates, such as Windrush Day (22nd June) – but remember to not limit your activity to just those days alone…

Diane Lee is teacher of English at Stowmarket High School, Suffolk. Pearson’s Lit in Colour Pioneers Programme supports schools in developing a more diverse English Literature curriculum through enabling free access to set texts, library donations of 300 books and providing responsive training. For more details visit go.pearson.com/litincolour

Writing from a different perspective to develop empathy

Jumping into someone else’s story not only improves writing, but helps develop pupils’ all-round empathy, says primary school teacher and English lead, Jon Biddle…

Helping children to think, speak and write from a perspective different from their own can sometimes be a challenge in the classroom. However, it’s an essential skill for them to develop and one that, with careful planning, you can teach.

The national curriculum states that pupils should have ‘opportunities to compare characters, consider different accounts of the same event and discuss viewpoints within a text and across more than one text’.

Providing regular chances to do this will certainly have a positive effect on their writing. But, on a wider and more important level, learning about the value of understanding different points of view and exploring situations from more than one perspective will also help them develop their own levels of empathy.

Sharing stories

Much of our English teaching at Moorlands is based around books and stories. We deliberately select texts for all year groups that enable perspective-taking.

The books we read during story time also provide a chance to ‘jump into someone else’s story’ and think about multiple perspectives.

This year, in my Year 5/6 class, we’ve enjoyed The Wrong Shoes by Tom Percival, Front Desk by Kelly Yang and Boy in the Tower by Polly Ho-Yen.

They’re all wonderful stories, with rich and detailed characters, and have all appeared on the EmpathyLab Read for Empathy collection booklists at some point.

Pupils love exploring the life of the character ‘outside’ of the book and discussing their relationships with family and friends.

It’s always fascinating to see how these views evolve over the school year and how the books often give children the confidence to talk about their own situations.

Writing with empathy

When pupils have learned the skills needed to produce a piece of work constructed from a point of view different from their own, they become able to write with cognitive empathy, using their inference and perspective-taking skills.

This will lead to them producing work that their intended audience will genuinely appreciate and enjoy.

However, there can sometimes be a struggle to move beyond ‘But I don’t actually think that’ and ‘I don’t know how they’re feeling as I’m not them’ conversations.

Sometimes, simply acknowledging the difficulty and rephrasing the question can help (I understand you’re not them and don’t know the answer, but how might you be feeling if you were?).

If you embed perspective-taking into your school’s long-term approach to teaching English and RSHE there will be dozens of opportunities to help children develop this skill during their time at school.

Acting out

It often helps to start a task with a drama activity, which allows the pupils to step into the shoes of different characters and see the world from alternative viewpoints.

The following established drama conventions can all help underpin and reinforce understanding of a character and their motivations:

- Conscience alley – a pupil takes on the role of a character and walks between two lines of people offering their advice

- Freeze frames – children work together to ‘pause’ an image from a book, while considering body language and emotions

- Hot seating – interview a child in role

When drama is part of regular classroom practice you can use it effectively in most curriculum areas. Pupils develop a deeper understanding of human behaviour and begin to understand that people have diverse backgrounds, values, and motivations.

Empathy emotions map

Creating an Empathy Emotions Map when reading a story is a useful way to keep a record of a character’s thoughts, feelings and actions, as well as their relationships with other characters, in a visual form.

We recently created one based around the character of Nate from The Final Year by Matt Goodfellow. You can do it as a whole class, but it’s also effective when you complete it in small groups or individually.

Several members of my class choose to create empathy emotions maps in their reading journals, which are based around characters from their independent reading books. This will sometimes develop this into a short piece of narrative or dialogue from that character’s point of view.

Writing a Perspective Journal can also be helpful when reading a book together. Thinking about the main five or six characters in a story and then writing a short entry each day from multiple perspectives can help pupils understand how different people might view the same situation.

There is a fight scene in Wonder by R.J. Palacio where this works wonderfully. Exploring the point of view of the antagonists is something the children enjoy doing and helps focus their thinking about the reasons behind the behaviour of certain characters.

Do as I do

As is the case with most writing, modelling the process, creating your own example and writing alongside the class, can be extremely powerful.

Recently, we learned about Captain Scott’s doomed expedition to the South Pole. Once they’d learned the details of the story, pupils were totally absorbed by the fact that he spent his last few days writing letters to his family in a freezing tent as an enormous snowstorm raged outside.

We read some of his final letters together and then tried to imagine what it would have been like to have been in his position.

Thinking from the perspective of Scott, I started to write my own ‘farewell’ letter with input from the class. I made a point of talking through my thought process and articulating how I, as Scott, would have been feeling.

I deliberately talked about the emotions I was experiencing (desperation, hopelessness, guilt and frustration, among many others), explaining what they meant, and tried to include these in my letter.

The children picked up on the language I was using and were then able to apply this successfully to their own work.

Varying perspectives

When you do this several times across a year it becomes something with which children are increasingly confident. It doesn’t always have to be a letter either. It could be a diary entry, a piece of dialogue, a poem, a comic strip, etc.

As pupils get used to writing from different points of view, they also get used to understanding real-life situations from varying perspectives.

An unkind comment in the playground, a tired parent or an upset friend become easier to cope with and understand when children have experienced similar situations in books, and explored them from the safety of a classroom environment.

The benefits of jumping into someone else’s story are apparent when reading a child’s individual writing. But, even more crucially, it’s also apparent in their levels of empathy and understanding of each other.

Building a more compassionate and empathetic classroom is a tiny, but essential, step towards building a more compassionate and empathetic world.