Transition day activities – Best resources for Year 6 / Year 7

As Year 6 students prepare to step into the exciting world of Year 7, use these transition day activities to help them feel confident, connected and ready for the journey ahead…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

From moving classrooms during the school day to managing a new daily timetable, the transition to secondary school has lots of challenges. These transition day activities will help students get off to a smooth start.

There are also ideas for working with your Year 6 / Year 7 colleagues more widely, for a longer period, to make sure transitions are as seamless as possible.

We also have more back-to-school activities here, including advice for making week one a success and 10 behaviour ‘do nots’ for the new year.

Table of contents

Transition day resources

Icebreaker activities

This free PDF features 13 ideas for getting to know your KS3 students and putting them at ease during their transition day. Ideas range from the alliteration game, shown above, to ‘Wow your word’, ‘Guess who’ and a fun drawing game.

Set goals for the upcoming year

This free resource pack from Plazoom makes a perfect transition day activity for your new starters. Use it to encourage students to set their goals for the upcoming year. You get a PowerPoint, printable booklet and teacher notes.

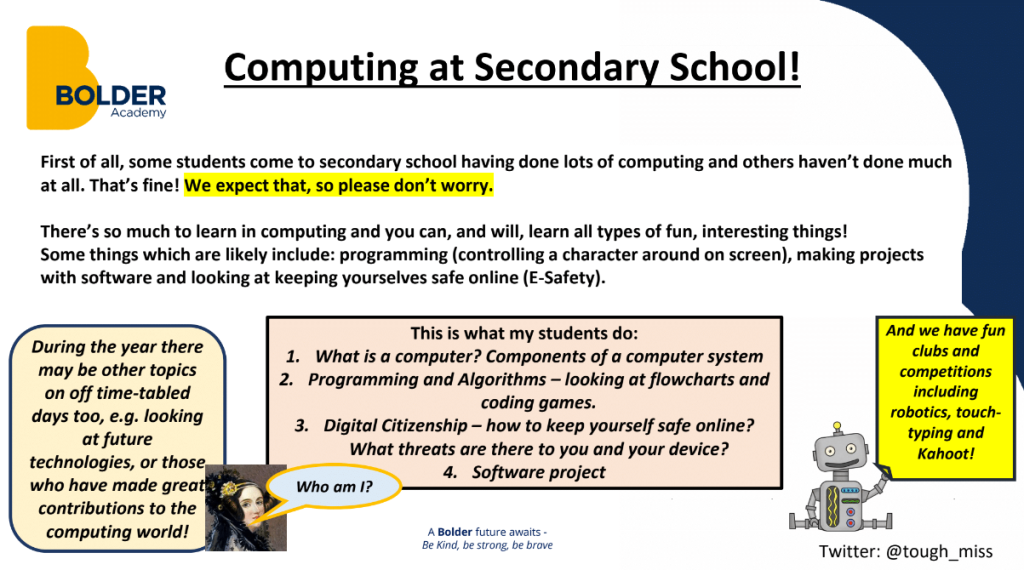

Subject presentations

Year 6 teacher Emily Weston reached out to over 30 secondary teachers from a range of subjects and asked them to create short presentations introducing their subject, a topic from it and a short activity children can complete. Download the presentations here.

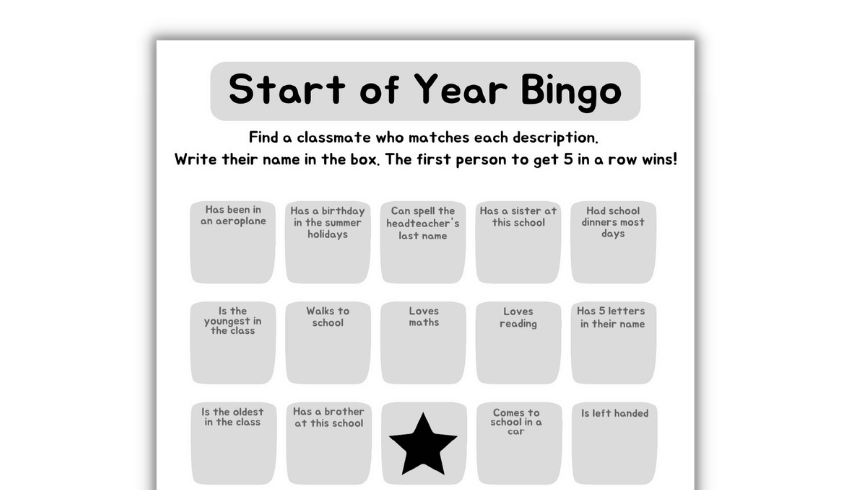

Back-to-school bingo

Help your new class get to know each other with this fun, free bingo game. The aim is to fill up the whole board bingo board, while also getting to know your new classmates better!

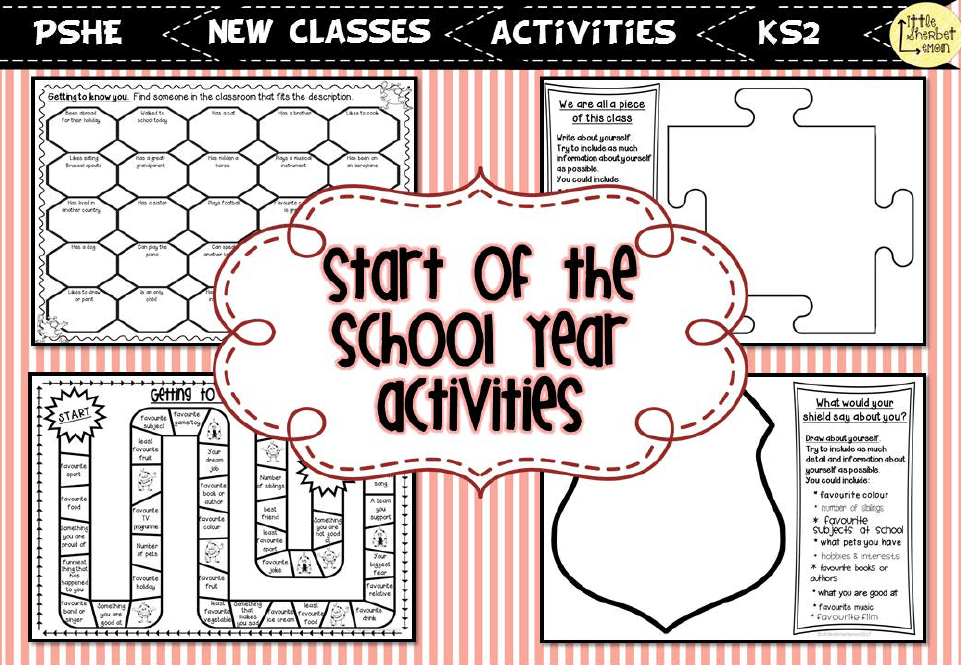

Back-to-school printables

Get your new class to learn about each other with these four back-to-school activities. Included are:

- ‘Getting to know you’ grid

- ‘Getting to know you’ game

- An activity where each student writes and draws about themselves for a class display

- ‘We are all part of this class’ activity where students’ individual puzzle pieces of their personality are weaved together

Raps about transition

Moving Up by writer, rapper and teacher Christian Foley is a friendly guide for children that will inform and reassure them about transition. It includes raps about common challenges and worries that children have in Years 6 and 7. Use these as a focus for one-hour standalone lessons.

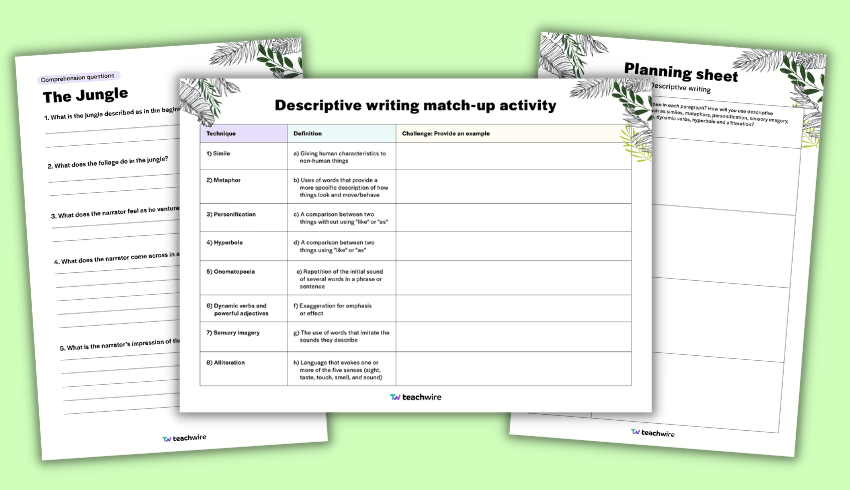

Taster English lesson

Help pupils get to grips with descriptive writing with these free Year 7 English worksheets. There’s enough content for two sessions and the download includes everything you need, including teacher notes and Powerpoints.

Transition day activities for Year 7 teachers

Getting to know you

This idea from Melissa Martin involves writing cryptic clues about yourself on the board and asking your new students try to work out what each means.

Write your name in the centre of the board and then surround this with about six or seven names, places, numbers and words connected to you. Students have to ask closed questions to guess how these words are connected to you, eg “Were you born in Durham?”

Students will be motivated by trying to find out more about you. Try to make some of the terms slightly ambiguous. Once the students have figured out all the clues, give them time to write their own, then get into small groups and take turns guessing each other’s.

Two truths and a life

Present three ‘facts’ about yourself – two true, one false. If you’ve seen the TV show Would I Lie To You? then you should already be fairly familiar with this concept.

Essentially you want to be presenting two interesting things you’ve done or that have happened to you, and mix in a lie. Obviously, the more outlandish the truths, the better the game is. It provokes more laughs and interesting probing to get conversation rolling.

More transition day activity ideas

- Think about offering residential visits to your feeder primary schools

- Arrange half-termly meetings between heads of Y7 and Y6

- Set up Y7 social media accounts and set prospective students daily challenges

- Organise visits by Y7 students to their respective feeder schools, where they present talks to Y6

Thanks to Rhiannon Packer and Amanda Thomas for these ideas. They are co-authors of All Change! – Best Practice for Educational Transitions (Critical Publishing).

- Create visual ‘classroom notices’ that can be given to Y6 pupils in June or July. They could include images of their new form room and form teacher, alongside a list of topics they can expect to be taught during the first term at their new school

- Organise summer holiday activities or club sessions for the Y7s starting in September, so that they can familiarise themselves with your school’s environment and potentially make new friends

- Host workshops in specialist teaching spaces (science labs, workshops, gyms), so that your incoming Y7s can get a sense of what their new learning environments will be like

- Have staff visit your local primaries to meet with their Y6 teachers and inclusion and pastoral leads

- Organise a summer meeting between your SENCo and local primary counterpart, and follow this up in autumn to review pupils’ post-transition progress and discuss whether any support options may be needed

Thanks to Clare Elson for these ideas. Clare is an inclusion and safeguarding lead.

Even more ideas

- Invite pupils in for a ‘Knowing Me, Knowing You’ day. Start with badge making so pupils have a chance to learn names and get to know one another. Put on lessons like D&T, science and PE. Host an oracy session where children discuss their feelings about starting secondary school.

- Visit feeder primaries as a TA, working alongside pupils’ regular teacher. After all, a piece of paper only tells you so much. Starting early means you know students’ needs and what to look out for. This way you can plan properly and be proactive, rather than just reacting to problems and issues.

- Run special transition day activities for children who are anxious or immature, or for children who have made poor choices in primary school and have perhaps been excluded.

- Run a group for your most-able new students. Ask primaries to recommend students who have high learning potential and invite them in special sessions. For example, do a project based on the Kate Greenaway medal and work together to review illustrated books and create your own. Pupils can also write their own IEPs (individual education programme), informing teachers how they like to be stretched and their preferred working environment.

- Invite children to ask prefects all the questions they are reluctant to ask an adult, such as which teachers are strict, how much homework they will get, what happens in detentions and important questions about toilets!

Thanks to Mariannina Turner for these ideas. She is Head of School for Year 7 and Transition at Ansford Academy.

Transition activities for Year 6 teachers

- Create a ‘this is me’ pack. This involves students writing a letter introducing themselves to their new secondary tutor, a ‘quick glance’ outline filled with their likes and dislikes and finally, a self-portrait to show their art skills. These packs really allowed children to present to their new schools what they are like as individuals; not just through their teacher’s eyes

- Try a ‘secondary week’, where children are on a secondary-style timetable. Ask different teachers or TAs to take classes. This is also another fantastic way to collaborate with your local secondary – why not ask them to take one or more of the sessions as an extra taster?

Thanks to Emily Weston for these ideas.

More ideas for Year 6 teachers

Use fiction to start conversations

A good story can begin all sorts of conversations about what’s worrying pupils, allowing them to explore their own feelings through those of the characters.

The security of displacement onto a fictional personality may reveal what’s going on beneath the surface of even the most hardened Y6. Zak Munroe Is (Not) My Friend by Simon Packham is a great place to start.

Case studies

Present a variety of potential situations pupils may encounter (or perceive they may encounter) in secondary school. Use these as a basis for discussion about ways to address them and the consequences these would bring about.

Topics suggested by pupils can be particularly powerful. Ask them to contribute anonymously through a worry box.

Role play

Rehearsing how to navigate some of the challenges of Y7 equips pupils with appropriate tools. Get them to enact asking for help with something they don’t understand in class or telling their adult at home they’ve got food tech tomorrow and need a shed load of ingredients.

Exploring different ways of saying the same thing may help them choose an attitude most likely to bring about a positive outcome.

WAGOLL

Use a WAGOLL (What A Good One Looks Like) to allow pupils to think about the characteristics they’ll be looking for in their new friends at secondary school.

Many pupils fear their old friends will abandon them but fail to consider their own behaviour. Talk about how things change and develop as they move to a new setting. What will they need to do to maintain old friendships as well as grow new ones?

Induction

Make the most of any transition visits. Encourage pupils to prepare questions in advance so they maximise the opportunity to speak with a member of staff from their new school.

Common concerns always include finding their way around, keeping up, homework, bullying and how lunchtime works.

Check to see if the schools offer any enhanced induction programmes to support vulnerable pupils. If there are former pupils who would present a positive picture of their move to secondary school, it might be reassuring for your Y6s to hear from them.

This is me

Spend some time talking with pupils about being comfortable with who they are, reminding them that trying to be someone you’re not is exhausting and never makes us happy in the long term.

Reflecting on their interests and hobbies as well as new things they’d like to try is a good way to encourage pupils to make the most of the many opportunities that lie ahead.

Joining a club will bring them into contact with those who enjoy similar pursuits and may spark friendships. It’s also a great way of reminding pupils that secondary school is not all about the challenges, but offers an exciting new adventure too.

Thanks to Simon and Deborah Packham for these ideas. Deborah is a former primary headteacher and lecturer. Simon is the author of nine books for younger readers including Worrybot and Has Anyone Seen Archie Ebbs?

Year 6 teacher tips for collaborating with secondary schools

Transition specialist Emily Weston explores what you can gain from creating stronger ties with local secondary schools…

While teaching Y6, one of the most valuable things I did was go to my local secondary for two mornings and observe Y7 lessons.

Often I was talking to Y6 about the next step of transition without entirely knowing myself what they were going into – it had been a while since I’d been in secondary school!

I focused on English and maths lessons as I wanted to see how they fitted in with SATs knowledge and understanding. Not only did I get to see secondary lessons in action, but I also got to see behaviour expectations, speak to teachers and even look over schemes of work.

It meant I was much more confident in making my classroom a perfect overlap of primary and secondary.

Secondary ready

Alongside this, I worked with the school to find out what personal qualities they felt Y7 needed to start school with in order to be ‘secondary ready’. From this, we collaborated on a series of lessons that focused on skills such as respect, independence and organisation.

It’s just as important to prepare children for these challenges, as well as ensuring they’re academically on track.

Now I’ve moved to secondary teaching I can also see that secondaries are very willing to work with local primaries, but unless there are established links this can be tricky. There’s also a focus on larger feeder schools which shouldn’t always be the case.

Reach out to your local secondary schools and ask what they can provide, not only in June and July, but in the months leading up to the summer too.

More transition ideas from Emily Weston

- Read sections of Go Big: The Secondary School Survival Guide by Matthew Burton as a class and discuss.

- Ask Year 7 students to write cards to the new Year 6 cohort giving friendly, empathetic advice. This makes them feel welcome and like they know someone already.

- Have transition ambassadors from a range of feeder primary schools. These pupils apply using an application form then help with primary outreach lessons and act as friendly faces when children arrive.

Supporting SEND students in the secondary school transition

As SEND students move from Year 6 to Year 7, you can play a vital role in providing the support and resources they need to thrive…

Case study: Cornwall Education Learning Trust

Cornwall Education Learning Trust (CELT), along with many schools across the country, is focusing on improving attendance rates, bringing them back to pre-Covid levels.

Keen to make a real change, we dug straight in with some data analysis. We found we needed to investigate SEND children’s attendance before we developed an overall strategy. Essentially, we knew we needed to do things differently.

We challenged ourselves with the following theory of change:

If we foster trusting, respectful relationships with our communities and families, focused on a shared commitment to the children, then we will be better informed, and develop deeper, more effective relationships to provide support and challenge. More children will feel a sense of belonging, be motivated to access school and achieve highly.

Our work has initially focused on the town of St. Austell. This includes one of our primary schools and one secondary school. Although, when we shared our theory with our SENDCos, several other schools within our Trust were keen to engage..

Improving the transition process

The first key area we decided to focus on was improving our transition processes for children with SEND from primary to secondary school. Our pilot secondary school, Poltair, developed its tailored transition to include a universal, targeted and bespoke tiered approach. This includes offering weekly transition sessions.

Trending

All Year 6 children were invited to ‘Easter Super Sixes’. These were fun sessions held at Poltair during the Easter holidays to support children to familiarise themselves with the school site while it was quiet.

The universal offer invites families to attend a session on Friday afternoons at the school. Children are asked to attend with a parent/carer so that the family can familiarise themselves with the school and build relationships with staff.

The school hosts thirty families each week throughout the summer term. Staff were conscious of possible cognitive overload for children at transition events, so they enlisted the support of the Cornwall Council ASD Advisor.

The advisor attended events with families and worked with parents at a separate session to share strategies to support their children through the transition.

Golden tickets

After meetings between primary and secondary staff, children who would benefit from enhanced transition support were identified and given a golden ticket.

The children and their parents were invited to smaller sessions with a maximum of eight other families to enjoy practical sessions such as pizza-making, with a higher ratio of staff in attendance.

We prioritised peer and staff relationship-building activities during the summer term, too. Targeted children were allocated a mentor, who checked in regularly.

There were also opportunities for the primary staff to join transition events and a check-in with children and staff during the first half of the autumn term.

For example, a new Year 7 SEND student with prior school anxiety attended weekly transition events, which reduced their concerns significantly.

This was complemented by regular check-ins at the Inclusion Hub, leading to an attendance rate of 97%. The family reported the transition as “seamless” due to tailored support.

Impact

Impact highlights included improved attendance, where Year 7 SEND attendance matched overall rates at 97%, demonstrating effective anxiety-reduction strategies, and enhanced parent and student voice.

Parents also praised proactive communication, including individual meetings, cafés, and tailored support plans. Families reported feeling connected and well-supported through regular updates and accessible SEND teams.

As far as pupil feedback goes, our learners said they valued opportunities to familiarise themselves with staff, peers, and the school environment through enhanced transition days, safe spaces, and targeted visits.

The SEN Year 6–7 Transition Project demonstrated measurable success in improving attendance and fostering a supportive environment for families.

Ongoing refinements, such as earlier planning and more inclusive activities, will strengthen future transitions. However, the most valuable takeaway is the true power of really listening to our families.

Claire Bunting has been a primary headteacher for over 10 years. Since September, she has been leading Cornwall Education Learning Trust’s Cradle to Career project, working with Reach Foundation, Feltham.

More ideas

- Put together a list of children in need of extra transition activities that you can pass to the relevant secondary schools.

- Put together pen portraits that outline each child’s needs and personality. This will help you identify the factors of transition they will most need support with.

- Invite secondary SENCos to discuss the children for whom they will be responsible. Develop transition activities together, using the pen portraits, to ensure that each child is appropriately supported.

- Assign a TA as ‘transition coordinator’. See if the secondary SENCo can link one of their TAs to your school in return. Visits by TAs between both schools will help to establish a sense of continuity and familiarity for the children.

Even more ideas

- Host a regular transition nurture group or lunchtime club. Invite a TA from the secondary school to come in and chat to the children. They can offer reassurance about issues relating to bullying and explain who will be there to help in the new school.

- Create transitional aids, such as a scrapbook containing photos taken from the children’s school tours. Use these as discussion prompts regarding new lunchtime arrangements, key members of staff, toileting arrangements, recreational areas and other details.

- Colour in floorplans to reflect subject areas.

- Combine mock timetables with map reading games to help children begin to understand how they will find their own way between lessons.

- Create a pictorial ‘Things to pack in my bag’ poster that children can keep at home.

- Use local maps and a storyboard template to look at children’s journeys to school. Organise a walk from the primary school to the secondary school

- Once they are settled, ask whether your recently departed pupils can send letters or posters to your incoming Year 6 children based around the theme ‘What I wanted to know before I started secondary school’. Peer advice carries credibility, and presents a lovely opportunity for you to find out how they’re getting on.

Getting parents on board

Invite parents of identified children to an event (no later than the end of the spring term). If possible, secure the attendance of a secondary SENCo, or arrange for another member of their learning support team to attend on their behalf if needs be.

Present to the assembled parents the planned activities for transition and additional strategies you have prepared, then invite questions that they can put to yourself and/or the secondary representative(s).

Try and arrange a couple of informal tours of the secondary school before the main induction days, giving children and parents a chance to look around when the school is quiet. Provide children and parents with an opportunity to ask questions of the secondary SENCo or TAs.

Thanks to Meriel Bull for these ideas. Meriel is a qualified SENCo and has taught in the West Midlands and Norfolk for over 12 years.

Why we host a whole transition week

The experience of starting Y7 can be confusing and intimidating – which is why one school resolved to give its new cohorts as much support as possible…

Each year for the past decade, we at Bedminster Down School, South Bristol, have run week-long programmes of transition activities.

We serve 22 primary schools and have a pupil admission number of 216 students in each year group. The student and parent feedback we’ve received strongly supports our choice to opt for a week of such activities, rather than the single transition day activities organised by most other secondary schools in the area. I’d argue the benefits definitely outweigh the costs.

Transition team

The transition team comprises three members of staff, including the school’s assistant principal, SENCo and a pastoral worker. They commence planning together in term 3. This involves information gathering and school visits during term 5.

My colleagues will speak with the SENCo and Y6 teachers, while I meet the students and answer any questions they may have.

We then plan out transition week itself. We always aim to hold it towards the end of term 6, to coincide with Y10 being on work experience and our Y11s having left.

The week is staffed by our own teachers – typically those that have surplus year Y10/Y 11 teaching time.

Transition week activities

Throughout the week, the Y6s will follow a timetable that closely resembles the one they’ll have when they start with us in September. They also take part in problem-solving and team-building events.

At the start of the week they attend a welcome assembly and there’s a rewards assembly at the end of the week.

Anxiety and nerves

What we’ve learned over the course of holding our transition weeks is that a growing number of Y6 students are demonstrating heightened anxiety and nervousness at the prospect of joining secondary school.

An overwhelming majority of these students say afterwards that temporarily joining the school for a whole uninterrupted week helped remove their anxieties around starting.

Needless to say, planning in a whole week of transition activities rather than setting aside a dedicated day entails considerably more work – but we’ve found it’s definitely worth it.

Daniel Goater is assistant headteacher and safeguarding lead at Bedminster Down School. For more details, visit bedminsterdown.org.uk

Providing support beyond September

Jodie Morris from Barwic Parade Primary in Selby explains how her school creates a sense of safety around transition…

My school serves an area of high deprivation, with more than half of our children eligible for pupil premium funding.

We know that a successful transition to secondary school is crucial for our pupils to succeed in their educational journey. Without a carefully designed package of support, we can lose some of them in that process through fixed-term or permanent exclusions.

We are many years into our journey as a Thrive school (a trauma-informed whole-school approach to mental health and wellbeing). We flood our children with Thrive support over the course of their primary years. However, when they move into secondary, this tight support network is sometimes lost.

Some of our children with gaps in their social and emotional development are very reliant on the relationships we have built. We don’t want them to lose that sense of safety when they move up to ‘big’ school.

Our approach to transition

Year 7 club

We run a Year 7 club during autumn term, where our leavers can come back each week to catch up with those key adults they are missing, and for us to listen and signpost them to support. They might be struggling with the work or friendships or may have received a sanction.

We talk to them about what happened. We might role-play the situation so they can try a different approach in the future.

The most important thing is that they know they are part of our school even when they leave us. We are here as familiar, friendly faces they can turn to for support whenever they need to.

1:1 visits

For the handful of pupils who may find transition trickier, we offer more support. This involves 1:1 visits to the new school. They walk around the school site, so they become familiar with the layout, experiencing the hustle and bustle of break times and lesson transitions.

They learn who among the high school students they can go to if they need support. We encourage these pupils to send postcards back and forth over summer term to continue strengthening this connection.

Other pupils who may struggle with the independence of high school visit it using a walking bus from our school, so we can point out the safest route and discuss risks.

Secondary PE lessons

We want the children to develop a familiarity with the school they will be joining, so we have a PE teacher from the secondary school deliver a weekly PE lesson for our Year 5 and 6 children.

The session is run exactly as it would be at secondary school, so the children develop a real understanding of expectations. It also means they have another familiar face when they start in September.

Jodie Morris is the attendance parent support adviser at Barwic Parade Primary in Selby. She is a Licensed Practitioner with Thrive, which offers a whole school approach to improving the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people.