KS1 reading comprehension – Best advice, worksheets and resources

Give Year 1 and Year 2 pupils a good grounding in comprehension skills in order for them to get the most from any text with these activities, ideas, lesson plans and other teaching resources…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Whether you’re a Year 1 or Year 2 teacher, enhance your teaching of KS1 reading comprehension with these ideas, resources and worksheets from fellow teachers and education experts.

(If you teach KS2, check out our reading comprehension KS2 round-up).

KS1 reading comprehension resources

Non-fiction and fiction worksheets

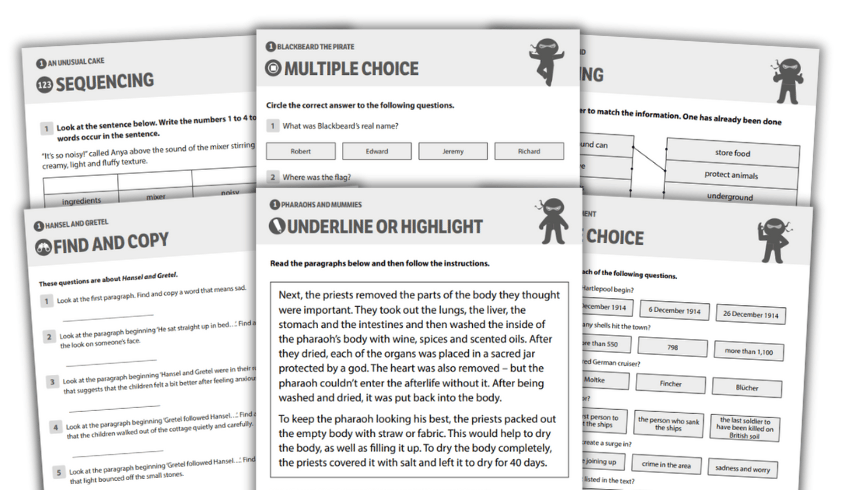

These engaging, free comprehension worksheets for Y1-6 cover fiction and non-fiction. Each high-quality comprehension text is followed by eight pages of questions.

Real Comprehension curriculum programme

Real Comprehension is a unique, whole-school reading comprehension programme from Plazoom. It’s designed to develop sophisticated skills of inference and retrieval and help children build rich vocabularies. It also encourages the identification of themes and comparison between texts.

Access 54 original fiction, non-fiction and poetry texts by published children’s authors – all age appropriate, thematically linked, and fully annotated for ease of teaching.

Build deeper understanding for children of all abilities through a variety of close-reading and guided reading techniques, plus fully resourced teaching sequences for every text.

Improve pupils’ ability to make high-level inferences and links between texts, and extend their vocabulary with focused lessons.

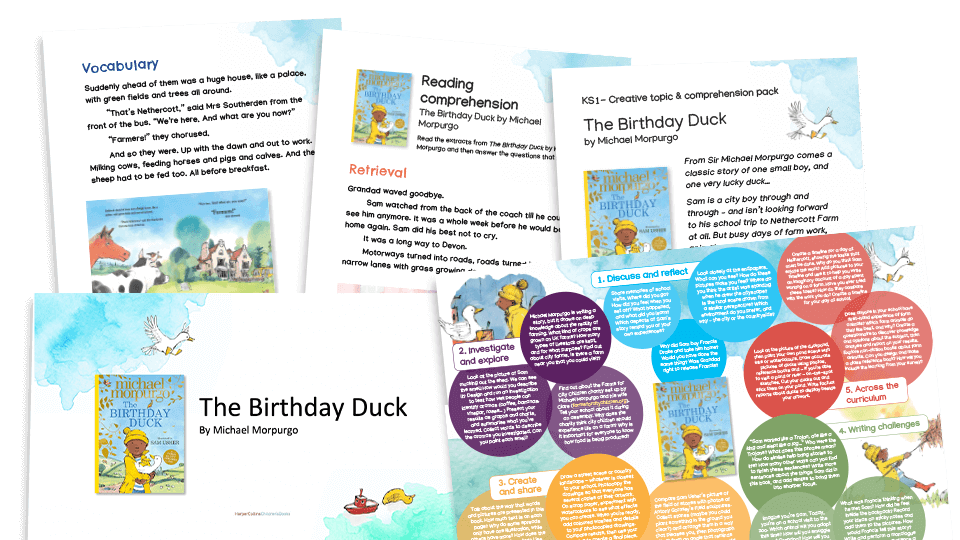

KS1 reading comprehension pack

The Birthday Duck is a delightful story by Michael Morpurgo. Use this free resource pack to plan a unit of work around this classic story to develop pupils’ reading comprehension and writing skills.

A topic map is provided, suggesting exciting writing opportunities and inspiring ideas from across the curriculum linked to the book.

Comprehension questions, based on short extracts from the book, will develop pupils’ understanding of what they have read, focusing on: retrieval, vocabulary, inference, sequencing and making predictions.

Goldilocks inference lesson plan

Inference is a crucial component of reading comprehension. Readers often need to make inferences to fully understand a text, especially when the author does not explicitly state certain information. Explore different versions of the classic tale Goldilocks in this free inference KS1 lesson plan.

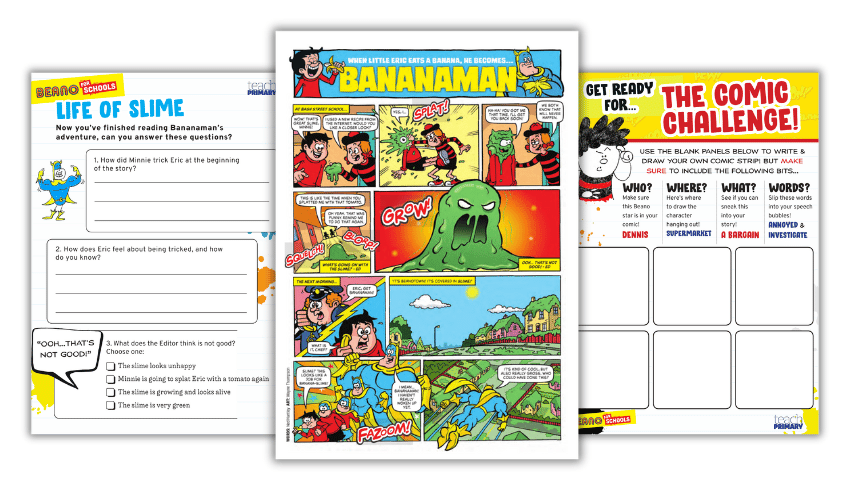

KS1 reading comprehension with the Beano

Use these fun comprehension activities themed around the Beano with your KS1 class. It’s a great way of getting everyone – including your typically more reluctant readers – to develop their reading skills.

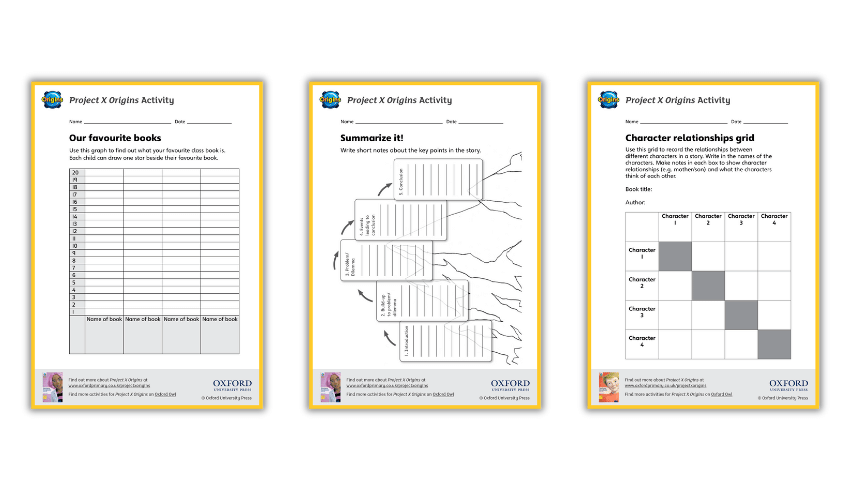

Oxford University Press worksheets

No matter what book you’re reading with your pupils at the moment, you can use these reading comprehension worksheets to help students track:

- what’s happening in the plot

- new words they come across

- characters’ emotions, attributes and relationships

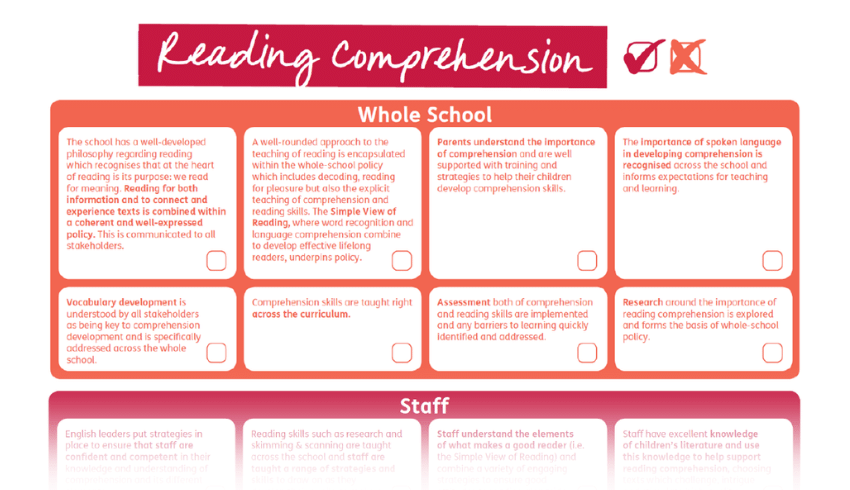

School reading comprehension checklist

Use this free checklist from the National Literacy Trust to review reading comprehension in your school. It includes tasks for whole school, staff and pupils. For example:

- Comprehension skills are taught right across the curriculum (whole school)

- The quality and effectiveness of shared and guided reading is carefully monitored (staff)

- Pupils are able to draw conclusions and make comparisons across different texts (pupils)

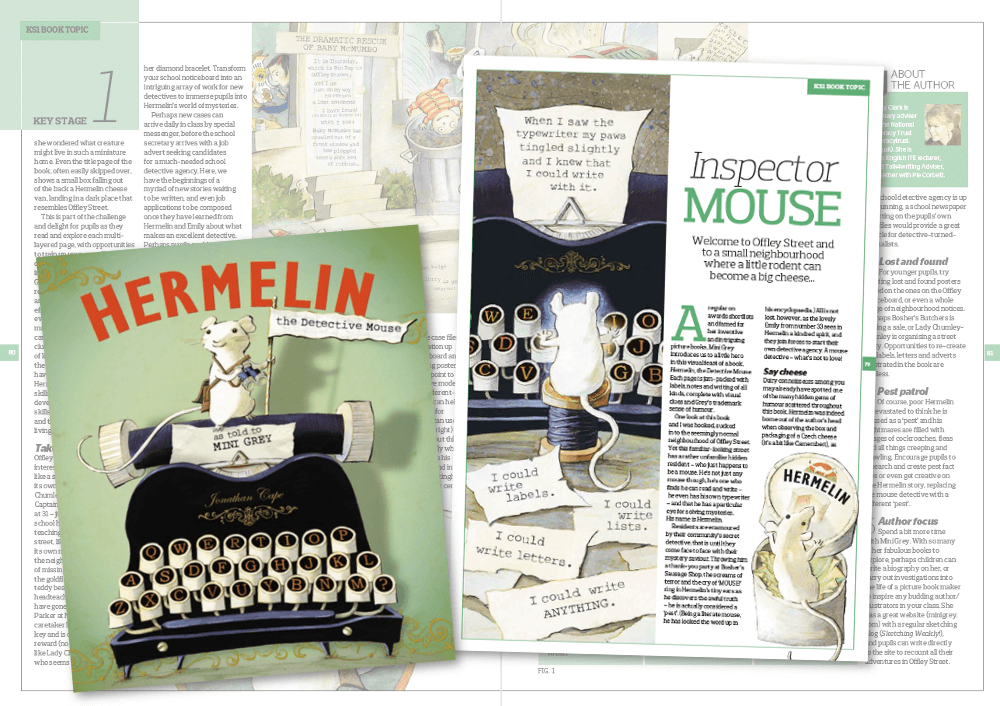

KS1 reading comprehension book topic

Boost inference and comprehension with Mini Grey’s mouse detective in this free KS1 book topic from Judy Clark, based on the book Hermelin: The Great Mouse Detective.

Pupils will need to scan the book’s illustrations for clues, making it an ideal title for comprehension work. Children will need to explain what they can observe, what they know and what they can infer from that.

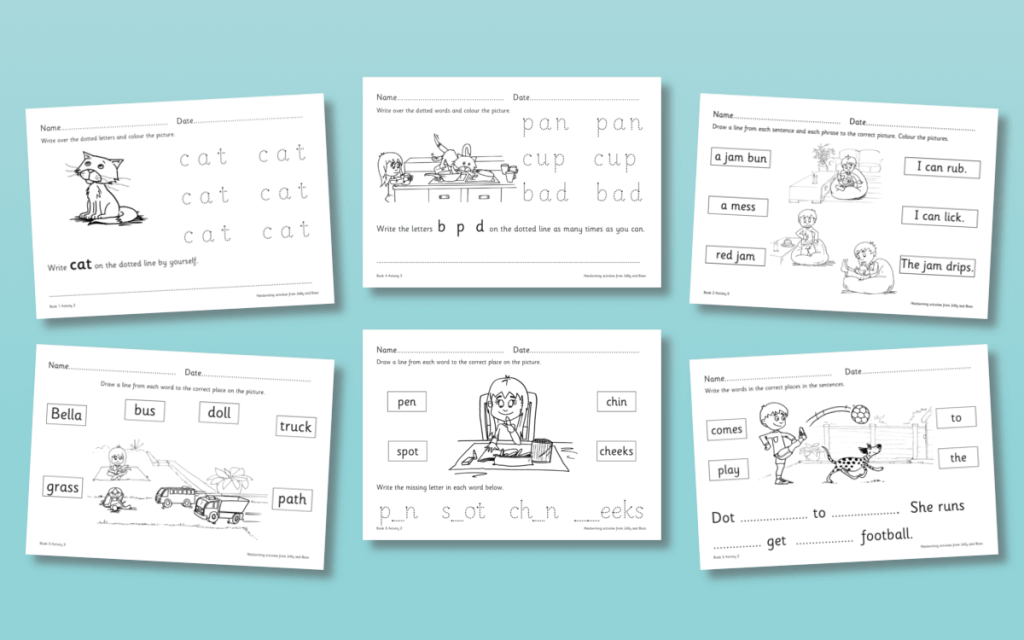

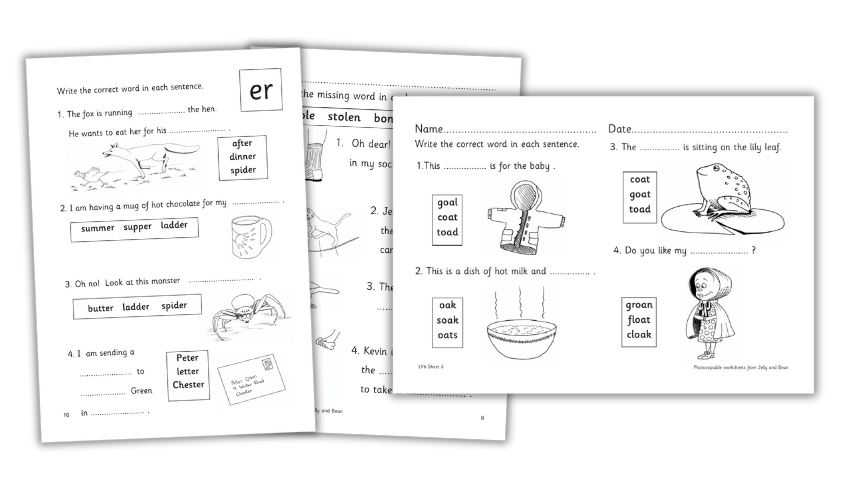

Tom and Bella KS1 reading comprehension worksheets

This set of six worksheets from Jelly & Bean lets children practise skills like letter formation (both with and without guides), handwriting, comprehension and there are pictures to colour in on each.

We also have lots more examples in our Amazing Handwriting Worksheets resource collection, including comprehension sentences featuring words that end in ‘er’.

BBC Bitesize video

This short BBC Bitesize video helps children to understand that when you read a text, link together the facts and clues to see the bigger picture and understand what’s happening, that this is called comprehension.

It will also help them find out what you need to do to work out what a text means.

Using picture books to teach KS1 reading comprehension

Comprehension has an essential place in your phonics lessons, says literacy consultant Jacqueline Harris, and your favourite picturebooks are an ideal jumping off point…

I wholeheartedly approve of systematic phonics teaching, but what with scrutiny from Ofsted and the Y1 check, the focus often shifts almost entirely onto decoding, rather than teaching children to read. In reality it should be a balance between the two.

I am, for example, a good decoder in Spanish as I studied it for a year at school. I know the correct pronunciations. However, I’m not a Spanish reader as I can only make sense of very few words. And my decoding skills are useless without comprehension.

If teaching children phonics is all about giving them the tools for reading, it seems to me that lessons need to focus on comprehension as well as decoding.

Understanding as well as decoding

This is why I use the application section of the lesson to make sure children truly apply their knowledge – that they are able to understand, as well as decode, what they are reading.

In my cautious early days of teaching phonics, I used the sentences in Letters and Sounds – that is until the day Thomas piped up with, “But why are we reading such silly things?”. This was when he was being asked to read, ‘Are fingers as long as arms?’.

He was right, I realised. Why would anyone be interested in reading that? So I started to use my own sentences for the ‘apply’ section of the lesson.

Choosing the right books

I began by making the sentences more interactive. I gave children a collection of pictures and a selection of sentences, each of which matched one of the images.

There would, however, always be one picture without a matching sentence. The children had to read and understand all the sentences to discover which one.

Then, when I was teaching /ar/, I realised I knew a good book, Ruth Brown’s A Dark, Dark Tale. This book features this Phase 3 sound, and I could use that instead.

I wrote my own version, making sure I used only decodable words with graphemes the children already knew. ‘On a dark, dark night in a dark, dark wood was a dark, dark oak. In the dark, dark oak was a …’.

This was instantly more exciting and successful in motivating them to read, particularly as I projected one of the beautiful illustrations onto the whiteboard.

Then, having read aloud the original book, we enjoyed talking about what the surprise ending might be in the version I had written.

Rewriting in decodable chunks

Some educators think you should not use books unless they have been written specifically for phonics teaching. But I believe you can use any great picture book, so long as you rewrite the story in decodable chunks.

It takes very little time as you are only looking for a couple of sentences to be read independently. Some books can provide greater challenge for more able pupils.

“I believe you can use any great picture book”

There are a limited number of words for the /z/ /zz/ phoneme (Phase 3), but there is a wonderful, memorable book to support this.

Ben’s Trumpet by Rachel Isadora is set in the 1920s jazz era. The marvellous black and white illustrations tell the story of Ben whose favourite place is the Zig Zag Jazz Club.

Start off the lesson by listening to jazz – it’s likely that many children will not yet have encountered the word. Then, when it comes to the apply section, you can just edit the book’s opening: ‘Ben sits next to The Zig Zag Jazz Club’.

This book rightly won awards. When using the story as part of a phonics session I’ve found it has far more impact than just reading the example from Letters and Sounds – ‘He did the zip up on Zenat’s jacket’.

Story recommendations for every phase

After trying this method of making the ‘apply’ section of the lesson more meaningful and enjoyable, I began to collect books to use for all the phases.

Phase 2

It’s trickier to find books at this level as the language tends to involve more than just simple CVC words, but there are some good options, including Duck in a Truck.

‘Duck has no luck, he is stuck.’ It’s not as good as Jez Alborough’s original rhyming text, I’ll admit, but it works well for /ck/.

‘Stuck’ is technically a Phase 4 word as it has adjacent consonants, but most children have no problem decoding it in their enthusiasm to read the story, and there are no new graphemes to untangle.

Phase 3

There’s no shortage of choice here. As well as The Dark Dark Tale, an obvious choice would be Shark in the Park (or Shark in the Dark) by Nick Sharratt.

Pig in the Pond by Martin Waddell is another lovely book and some of the pages require very little editing. This works well once children have begun digraphs and need a bit of revision of the early ones.

‘The pig sat in the sun. She looked at the pond. The ducks went “Quack!” The geese went “honk!”’.

Phase 4

Here things get a bit harder once again due to the increasing complexity of texts. However, there are options that highlight adjacent consonants well and help children revise previously learnt graphemes.

Mr Gumpy’s Outing by John Burningham, for instance, is one of those clever books where each word has been chosen with great care, even though at first glance it appears quite simple.

It really lends itself to comprehension. “The goat kicked, the chickens flapped, the pig mucked about…”. There’s a good conversation to be had about the way the word ‘mucked’ is used in that sentence!

Phase 5

This is a return to easier ground. There are dozens of options, with The Smartest Giant in Town by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler being one of my favourites, and useful for assessment.

You can be sure that any child who is able to read the letter at the end of the book has a very sound grasp of Phase 5.

Quentin Blake has written a couple of great books suitable for phonics teaching. Mr Magnolia is fantastic for exploring different ways of spelling the / oo/ phoneme (flute, newt, boot and suit). Fantastic Daisy Artichoke provides lots of options for /oa/ (croak, stroke and folk).

Finally, if you are looking for a book that makes good use of nonsense words, Lynley Dodd’s The Dudgeon is Coming is a good example.

Alongside the Dudgeon, other characters have unconventional names that require decoding skills, eg The Bombazine Bear and the Purple Kazoo.

The most important thing to remember when using books is not to give children ‘extractitis’ and always make sure you read and enjoy the whole book together. After all, that is the point of learning phonics!

Jacqueline Harris (@phonicsandbooks) is a literacy consultant and passionate advocate of high-quality children’s literature.

How to use role play to enhance KS1 reading comprehension

Giving time over to drama lessons may feel like a risk, but it’s certain to deepen children’s understanding of fictional narratives, says former primary headteacher Ruth Baker-Leask…

Not every teacher’s encounters with drama are positive. We have all experienced that stomach-lurching moment when, during a training session, an overzealous course leader asks you to try ‘a bit of role play’.

Drama can feel daunting, and it would be easy to leave it in the hands of the talented, uninhibited few. However, many children have an often undiscovered natural talent for drama, and most pupils enjoy and engage with role play activities.

Drama is a useful method for teaching curriculum content, particularly reading and writing. And the well-worn quote from To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee illustrates why we should be turning to role play as one of the essential teaching strategies we use to support children’s understanding of narrative:

“You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view…until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” Atticus Finch

During the teaching of reading, drama and role play can support children to:

- engage with texts they might otherwise find difficult

- understand plot and action

- understand a story’s setting and how this influences action

- predict and discuss future actions and their consequences

- understand and discuss mood and atmosphere

- understand characters’ traits and infer their feelings, motives and intentions

- explore the language used by characters to express thoughts and feelings

Why role play?

From an early age, children explore worlds, real and imagined, through the act of role-play. In Early Years they are provided with a range of opportunities to engage in imaginative play such as role-play areas, puppets and props, and through the act of small-world play.

Role play becomes more structured for older children but still provides the same benefits. It strengthens their comprehension skills by supporting them to make connections between a fictional world and their own lives.

It also provides children with opportunities to explore scenarios within stories, considering their importance and consequences.

“Role play becomes more structured for older children but still provides the same benefits”

In addition, role-play contributes to children’s language development as well as developing confidence and creative thinking. It also strengthens collaborative relationships within the classroom.

Understanding book characters with Role on the Wall

Role play involves inhabiting the characters and their fictional world. Therefore, it’s best to give children time to explore these characters through book talk and discussion before leaping headfirst into a drama activity.

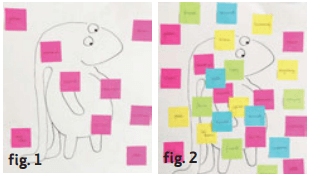

Role on the Wall is a great way to do this and can be revisited at any point as a story progresses. Here is an example of a KS1 Role on the Wall of Beegu, from the popular book by Alexis Deacon.

Fig 1 shows how the character feels (inside her outline) when she finds herself stranded on a strange planet. Around the outside of her outline are words that illustrate how others perceive Beegu (both her character and her appearance).

Fig 2 shows how you can add to and alter a Role on the Wall as a story progresses. This allows children to notice how characters develop throughout a narrative. Each coloured sticky note represents a different moment in the story.

Role play activities to try

Role play activities can be short and easily delivered during book talk or shared reading lessons, eg quickly hot-seating a character at a crucial moment in a story or taking a moment to explore a character’s thoughts using a freeze frame.

However, sometimes you may wish to make role-play the main event. In this case, you have to create or find plenty of space (every teacher should have a ‘move the tables back’ plan up their sleeve), and not feel guilty for taking a couple of hours out of the week to indulge in a bit of drama that might not have any form of written outcome.

These are some of the techniques I like to use most often:

Overheard conversations

In groups or pairs, improvise conversations between key characters. The teacher and other class members eavesdrop and report back what they heard.

Telephone conversations

Mock call each other in role as characters from the story using the appropriate tone and language.

Flashback or flashforward

Role-play a scene from before the beginning of a story, or what happens after the story finishes.

Gossip

In role as a chosen character, the children gossip about each other, making reference to critical events in a story.

Imagined characters

Sometimes it is useful for children to stand back from the action and adopt a different point of view. This is easily done by inserting new characters, who are imagined observers of the story, into a role play. For example:

- Policeman sent to the scene of a crime within the story

- Character’s teacher who is talking about one of the characters during parents’ evening

- Town councillor making an announcement about events that have affected the hometown of the character

- Character’s parent or friend discussing their concerns

- Bystander gossiping about an event in the story

- Local wise woman, etc

Writing in role

Writing in role is a worthwhile extension to most drama activities. It offers children a further opportunity to express a character’s thoughts and feelings and allows them to reflect on the text as a whole.

Writing in role provides children with an authentic purpose for their writing as well as enabling them to write freely, unrestrained by the expectations of more formal writing lessons. They might choose to write in role a:

- Social media post

- Packing checklist

- Travel blog

- Diary

- TV/radio interview

- Resignation letter

- Informal note to be slipped under a door

- Thank you card or letter etc

Get involved

As you can see, drama and role play can support teachers to deepen children’s understanding of text in varied and engaging ways. This means you can avoid the temptation to only teach reading comprehension through the model of teacher questioning.

Using role-play as part of your teacher’s toolkit can be significantly enhanced when you get involved yourself (oh, there’s that familiar stomach lurch!).

“Avoid the temptation to only teach reading comprehension through the model of teacher questioning”

No one likes to make a fool of themselves, but your children would appreciate it if you did. To fully immerse children in any dramatic scenario, you might need to jump in with them.

A former primary head, Ruth Baker-Leask is director of Minerva Learning and chair of the National Association of Advisers in English (NAAE).