Some Friendly Advice For Newly Appointed Heads Of Department

You may be a fantastic teacher, says Dr Joanna Rhodes, but heading up a department means working on a whole new range of skills and strategies…

- by Dr Joanna L Rhodes

- Vice principal at Leeds Mathematics School

Teachers all share a common goal: to inspire, enthuse and engage our students. Successful ones generally do this exceptionally well, with new teacher training remaining focused on strategies for assessment for learning, menus of starters, mains and plenaries and endless lectures, courses and books about behaviour management.

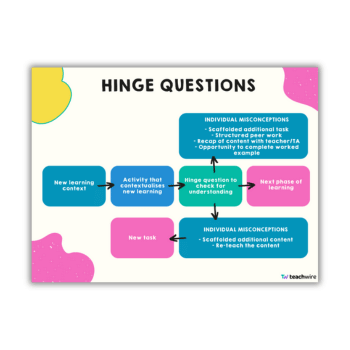

But try this. Take your most successful teachers, with their folders of hinge questions, and ask them to manage a team. Not a team of students, at which they would excel, no – a team of adults. Ask them to performance manage, line manage, recruit, encourage, facilitate, empower, organise, observe and maybe even discipline members of their team – and insist that they do so with only a modest reduction in their teaching timetable. Oh, and you could invite Ofsted in just for good measure…

Drifting out

Having painted this rather daunting picture, it’s probably worth mentioning that this is the same situation I once found myself in. Having been successful in managing a small suite of applied qualifications, I went for the top job, and got it – director of science. I was (and still am, despite what I am about to describe) exceptionally pleased, proud and excited.

It was with a sense of passion and purpose I spent the summer holidays beforehand planning, drawing up grids, sending countless emails to science department staff and rewriting the whole faculty handbook, creating a new assessment policy and producing the biggest self-evaluation form the school has ever seen (or so I was assured by the principal). My department development plan was ambitious, detailed and triple-spell checked by my long-suffering husband.

This bubble carried on into September. Having initially made a good recovery on the INSET day, I soon discovered that no-one had read any of my emails and raced through everything on the day. At home that night I announced that everyone had ‘taken on board the changes’ and that ‘it was going to be a great year’. However, as I dropped in on lessons, arranged assessments and emailed countless updates to topic rotas and meeting agendas, I realised not much seemed to be changing around me. People were getting on as normal; that is to say, as if I didn’t exist.

There was no evidence that my ambitious DDP was being acted on and my assessment policy had drifted out of the collective department consciousness as quickly as it had drifted in. Then there was the ‘Mocksted’ very kindly arranged by the SLT, so we could practice for the real thing. For science, it didn’t go too well – a fact that I robustly presented to the department, along with a salting of ‘You see, you should have been listening to me all along‘…

Going off the rails

By November the train was beginning to derail. My frantic emails about refreshing displays in classrooms and inputting tracking data onto the system crept later and later into the evening (well, into the night actually) and seemed to progressively achieve less and less. Paranoia set in, and I became convinced that my colleagues actually wanted me to fail.

With hindsight, this is when I probably should have asked for some help. I struggled on until February, before realising that I had managed to dig myself a massive hole and needed some help getting out of it. Finally (and with rather wounded pride) I asked for some support, and with the help of SLT and the TLR holders in the science team, began to get myself back on track so that we could all start to make some progress together.

The year did ended with some successes. The school achieved outstanding in the real Ofsted inspection, and the science department performed very well. For me however, the biggest achievement was recognising that I needed to learn to lead and to ask for help.

I still remain the same person – a workaholic obsessed with perfection – but you would be less likely to notice this now (I hope). I would like here to share with aspiring, new and existing department and faculty heads some of the strategies and ideas I have learnt from other remarkable people, from the moment I asked for help and started listening.

Communication

Most of my initial communication was by email, and I made the assumption people would read it, understand it and act on it. At the time, I was surprised and disappointed that very few of my staff did – but just like students, different staff need to be communicated with in different ways. I needed to learn about the people I was working with in a way I hadn’t done before.

So I began to do the classroom rounds, speaking to people and then following up with an email or even a post-it note. Some staff responded really well to a note in the pigeonhole, while others liked to be collared over coffee or while on duty. The other advantage of more face-to-face communication is that it allows you to gauge a response and take on other views.

Communication also requires understanding and understanding needs checking, so I started following up with staff, checking their understanding of the message, asking them to remind me what we discussed or to confirm back to me by email the actions we agreed.

Buy-in

One of my biggest mistakes was presenting a range of finished products to staff and expecting them to be pleased that I had saved them time and just go with it (see the new assessment policy, for example). But because none of the staff had any interests vested in the success (or otherwise) of the policy, there was no reason for them to try – and minimal consequences if they didn’t, because no one else was doing so either.

I learnt that it’s possible to know where you want to get to, but that you have to let your staff take you there if you have confidence to trust them. Steer the direction you want to take the department not by policymaking, but by posing simple yet challenging questions and asking your team to come up with the answers. For example:

1. What are the strengths in how we currently assess students? 2. What are the weaknesses in how we currently assess students? 3. What changes do we need to introduce?

The result for me was that staff were willing to change, because they had identified the need to do so themselves. This becomes very powerful, as staff will also informally hold each other to account if someone is not seen to be joining in, and it maximises the sense of cooperation and teamwork. This approach activates your staff as the most important and insightful resource in your department or faculty.

Positivity and Praise

They way I fed back the Mocksted judgments to my staff provides me with one of the more toe-curling moments of reflection. I passed the information on in much the same way as it had come to me, which was lacking in constructive thoughts and with a little ‘I told you so‘ thrown in for good measure.

It’s very hard not to do this when you are frustrated, could see the end result coming and couldn’t get anyone to listen to you. However, there are better ways to approach such challenging circumstances. I could have picked out the one classroom display that was complimented and showcased it to staff; I could have asked the teacher rated good with outstanding features to give us a summary of her lesson and share her lesson plan; I could have asked staff to offer their opinions of how it went, and followed up by asking them how we can improve, together.

How to praise is a sensitive area, and it’s really important to learn how each individual would like to be praised – in front of the team, or quietly and in private.

Widen the team

There are countless people in supporting roles working hard to make each day a success, including teaching assistants, technicians, the caretakers, finance, exams and secretarial staff. Ask to go along to their meetings, invite them to yours and find out what they need from you to help them in their jobs. Get their support with changes and improvements you want to make.

You can also encourage your staff to take and make the calls home to parents, in order to build personal relationships and improve parental engagement, but be there to support them and follow up if conversations are difficult.

Teachers are rarely appointed to management roles because of their skills in that area, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have them or can’t learn them. Taking the time to value, empower and get the best out of those around you is not just a strategy – it’s a way of improving your working life, and an ancillary benefit is that is just happens to be one of the best routes I’ve found so far to becoming a more successful leader.

Dr. Joanna Rhodes is associate assistant principal at Shelley College, Oxford