NPQs – Why haven’t we made the most of them?

The excessive workload that teachers and leaders carry has stopped us taking full advantage of a free CPD offer, says Sarah Botchway…

The government introduced the first NPQs (National Professional Qualifications) for headteachers in 1997.

But it wasn’t until 2017, when it introduced three more NPQs for middle, senior and executive leaders, that they really entered education consciousness. Now you’d be hard-pressed to find a teacher who hasn’t heard of them.

The DfE recommends NPQs as the go-to programme for professional and career development. This is so much so that it discourages any competing programmes. The NPQs are now on their third reform, with a plethora of new ones (nine in total and a tenth on its way in September).

Since 2021, the DfE has invested £184 million to ensure all teachers in the state sector can do an NPQ for free. However, with the current funding stream of NPQs expected to end with the spring cohort, have we made the most of this opportunity?

So far 35,666 teachers have opted to do at least one of the new NPQs, which equates to 6.3% of the current workforce – well short of the DfE’s target of 150,000 teachers. This got me wondering why NPQs haven’t been as popular as expected.

A free lunch

We all know that teachers get excited about getting a freebie. New books for the library, a free lunch on a course – even complimentary tea and coffee in the staffroom – can feel like the ultimate treat. Our perks are a far cry from the huge bonuses and lavish gifts seen in the private sector.

My non-teacher friends are always astonished when I tell them that staff Christmas parties are often in the staffroom, where we bring our own food and drink! Surely fully-funded, high-quality professional qualifications retailing between £1,000 to £4,000 would be the ultimate jackpot? So, why has the uptake been so small?

As director of a Teaching School Hub offering NPQs, I hear a range of reasons why teachers take on this CPD. Some of the most common are pressure from school leaders; making the most of a freebie; or (my favourite), “Others have done it, so I may as well do it too.” Lastly, some opt to embark on the NPQ journey because they have a thirst for knowledge and relish in the opportunity to learn something new to enhance their practice.

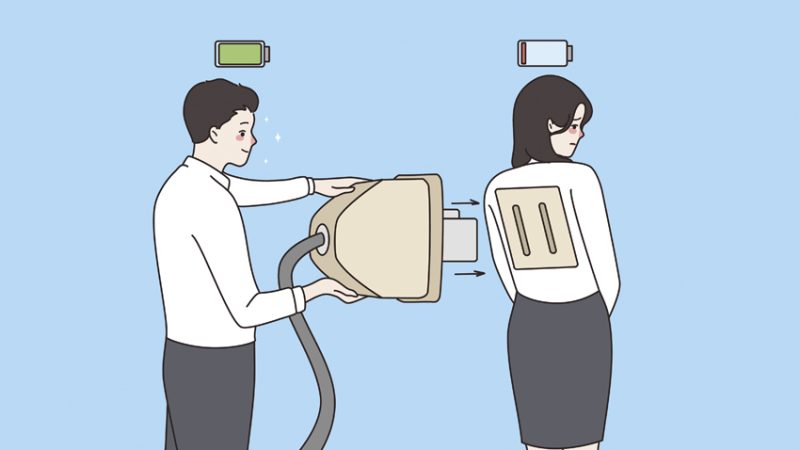

Sadly, I think the excessive workload that teachers and leaders carry has had an impact on them taking up this opportunity. Adding another layer of teaching activity on top of what already feels unmanageable can become too much. We’re all too aware that adding one more spinning plate to the many already on the go can bring everything crashing down.

Facing the future

So, without continued funding how will this DfE flagship programme survive? As workload remains high and school budgets limited, school leaders will be in an impossible position: unable to afford NPQ costs and unable to release the time needed to manage workloads. This will inevitably lead to even fewer teachers taking on this qualification. There is an expectation in other industries for professionals to continue professional development throughout their career; NPQs provide educators with that same opportunity of professional development.

Where recruitment and retention in schools are challenging, having an NPQ often isn’t the deciding factor of whether a teacher is interviewed or offered the job. Nevertheless, completing these evidence-based qualifications deepens skills and knowledge, which in turn improves confidence. And that confidence in practice and knowledge can lead to career progression.

Nobody I know has regretted doing an NPQ, even with initial fears of additional workload to contend with. Evidence shows that more than anything else, the biggest impact on pupil standards is high-quality teaching. Therefore, any opportunity to improve this should be a priority.

Rather than removing the investment, the DfE and educators should be working together to eliminate all barriers to access for these programmes, and promoting them further for current and future teachers and leaders.

Sarah Botchway is the director of the London South Teaching School Hub, responsible for the training of teachers through primary to secondary across Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham. As a teacher, she taught at all levels from primary to adults, and was head of school at Reay Primary.