SATs 2025 – The ultimate teacher guide to preparing pupils for Key Stage 2 assessment

How to prepare pupils for this year’s SATs and make sure they get the scores they deserve…

- by Teachwire

Whatever your thoughts and feelings are about SATs, and tests in general, naturally you’ll want your pupils to do as well as possible, without causing them any stress or worry along the way.

We’ve picked out a selection of resources that can help consolidate children’s learning and prepare them for KS2 SATs, without making it feel like a big, dark educational cloud is looming on the horizon…

(We also have a post about the optional KS1 SATs).

Table of contents

When is SATs Week 2025?

KS2 SATs are due to take place between Monday 12th May and Thursday 15th May 2025.

The timetable is as follows:

| Monday 12th May | English grammar, punctuation and spelling papers 1 and 2 |

| Tuesday 13th May | English reading |

| Wednesday 14th May | Mathematics papers 1 and 2 |

| Thursdays 15th May | Mathematics paper 3 |

When are SATs results 2025 announced?

Headteachers can view results from 8th July 2025. Parents will also receive results around this time. Schools’ performances will be made public in December 2025.

SATs scaled scores 2025

The government will make scaled scores for 2025’s SATs available in July 2025.

KS2 SATs access arrangements

Some pupils with specific needs may need additional arrangements so they can take part in the 2025 KS2 SATs.

This could include, among other things, additional time to complete the test, the use of electronic aids or the use of rest breaks.

Read the government’s guidance for schools about access arrangements here.

KS2 English SATs resources and advice

KS2 English – SATs practice tests

You can find KS2 past papers from 2022-2024 on the government website.

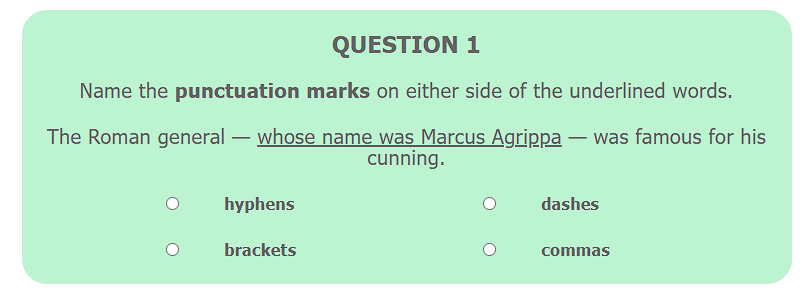

Make sure Year 6 pupils are prepared for SATs with Plazoom’s KS2 SATs Support collection. It contains reading test practice packs and ten SPaG practice papers. It also contains writing evidence activities and fun ‘Revision Blasters’ that are linked to content domains for grammar.

Each Revision Blaster grammar pack includes a recap section for reteaching and a practise section with SATS style questions. They’re perfect for SPaG revision in Year 6.

SPAG practice papers

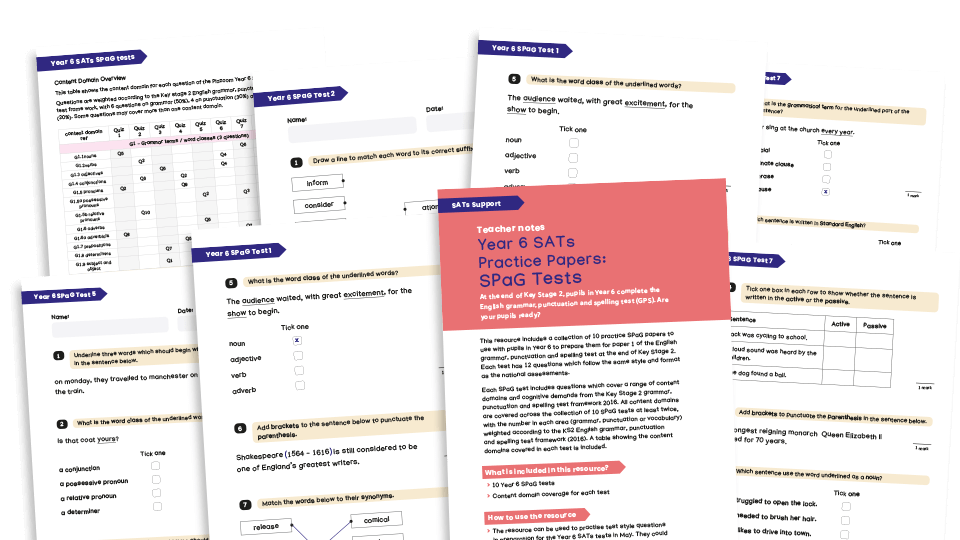

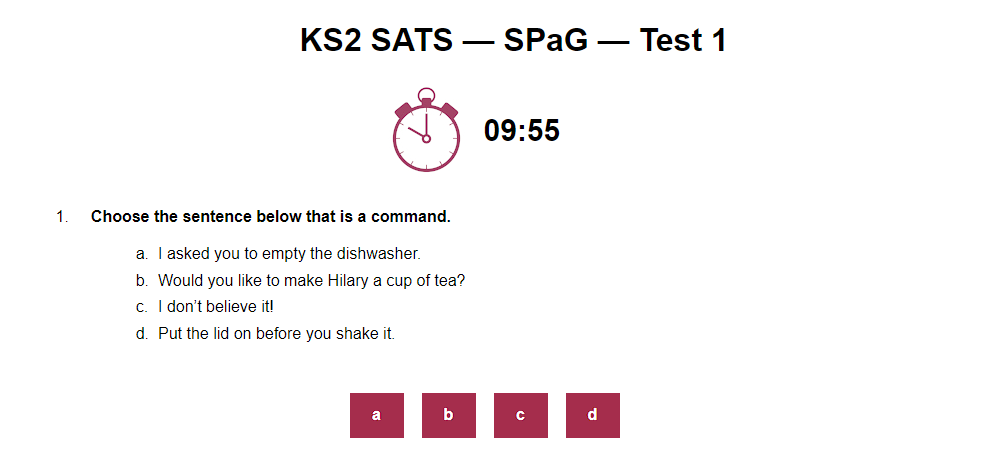

These ten practice SPaG papers from Plazoom feature 12 questions which follow the same format as paper 1 of the English grammar, punctuation and spelling test. All content domains are covered across the collection at least twice.

SPaG practice papers

These free grammar, punctuation and spelling practice test papers from STP Books are modelled on actual SATs exams. They come with complete answers and marking guidelines.

Year 6 SATs spelling practice

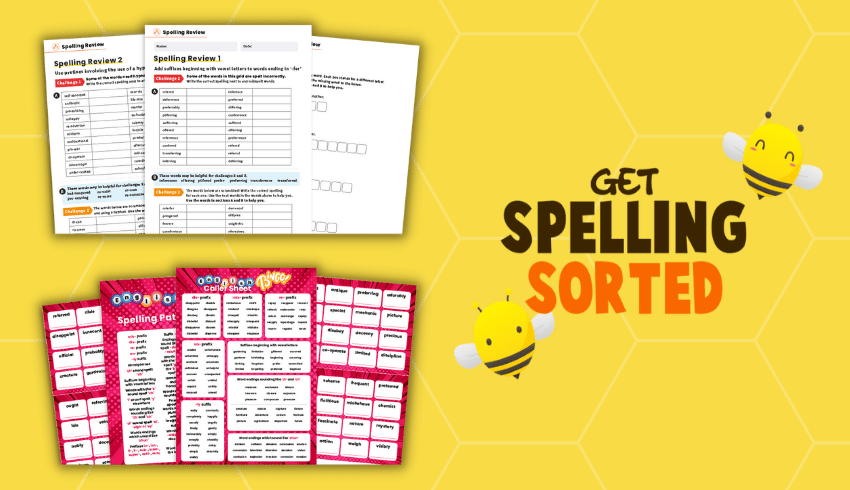

If you want to focus on helping children learn and master spelling patterns, rules and exceptions, visit the Get Spelling Sorted collection on Plazoom. It’s a great repository of revision games and activities.

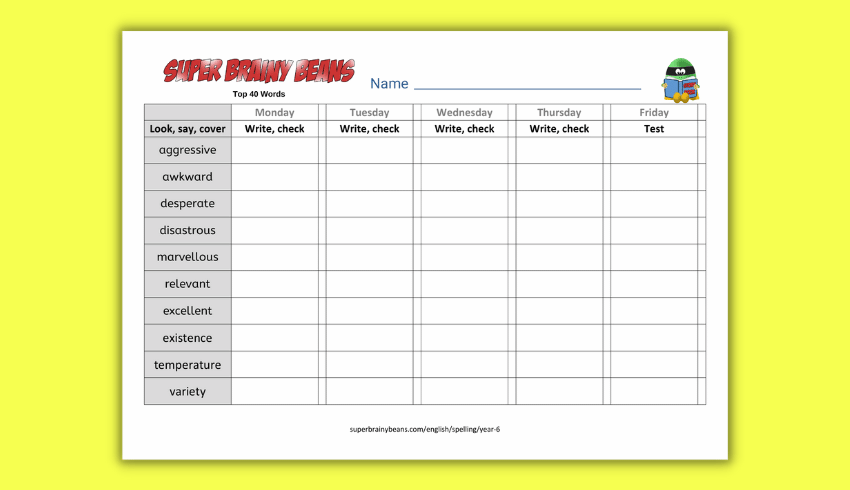

Use this free top 40 words spelling sheet download in Year 6 to practise these common and sometimes tricky words.

Browse more Year 5 and 6 spelling list resources.

Year 6 SATs writing evidence

If you need to gather more independent writing examples to assess Year 6 pupils against the writing Teacher Assessment Framework, use these Year 6 SATs Writing Evidence packs from Plazoom. They’re specially designed to get children producing authentic, independent writing.

Each set of activities is linked to foundation subjects, providing opportunities for cross-curricular writing. For example, write a:

- non-chronological report about bridges

- persuasive report about keeping healthy

- diary recount of an historical event

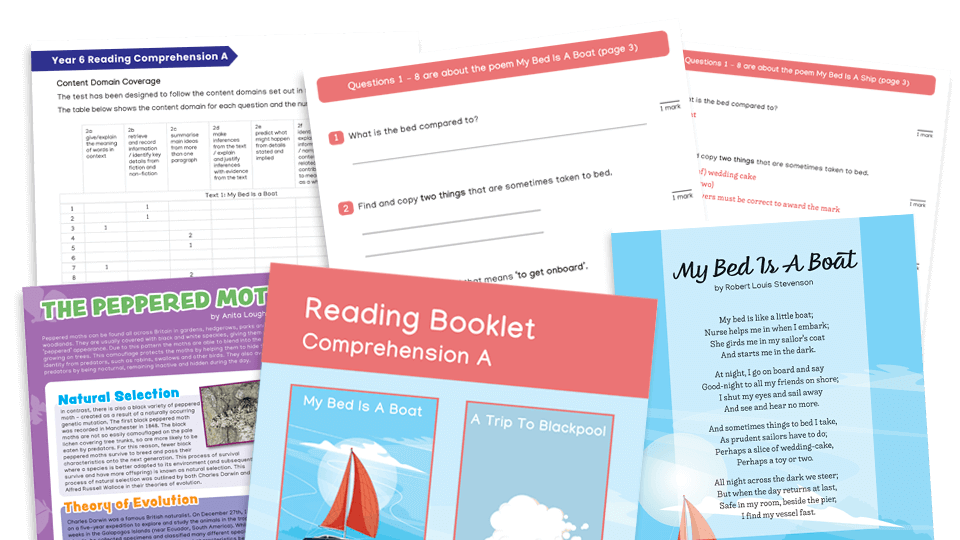

Year 6 SATs comprehension

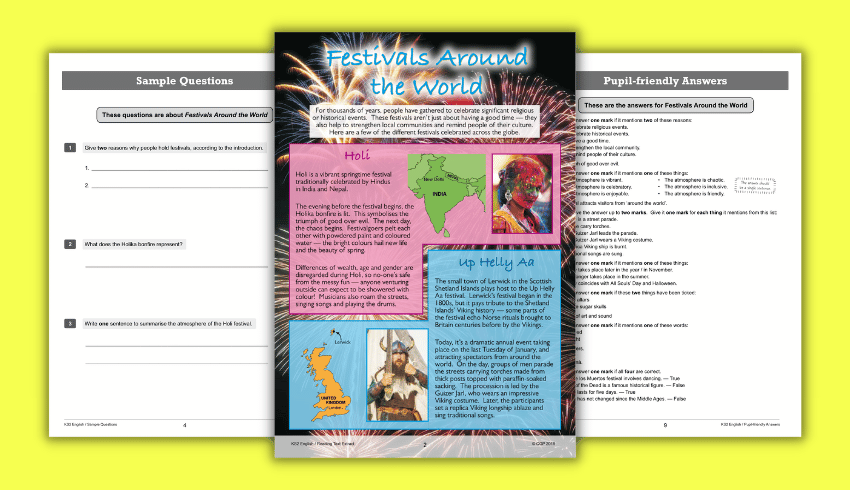

This free sample practice paper from CGP contains a reading text extract, questions and pupil-friendly answers.

If you’re looking for more Year 6 SATs reading comprehension practice PDFs, try these options from Plazoom.

Each of the three packs has been carefully designed to follow a similar format to the SATs. This means your pupils can become more familiar with their layout and improve their confidence.

Use them as practice tests or use them as part of group or whole-class reading sessions. You could also use them as smaller comprehension activities where pupils read the text and complete the questions.

Choose from Set A, Set B or Set C.

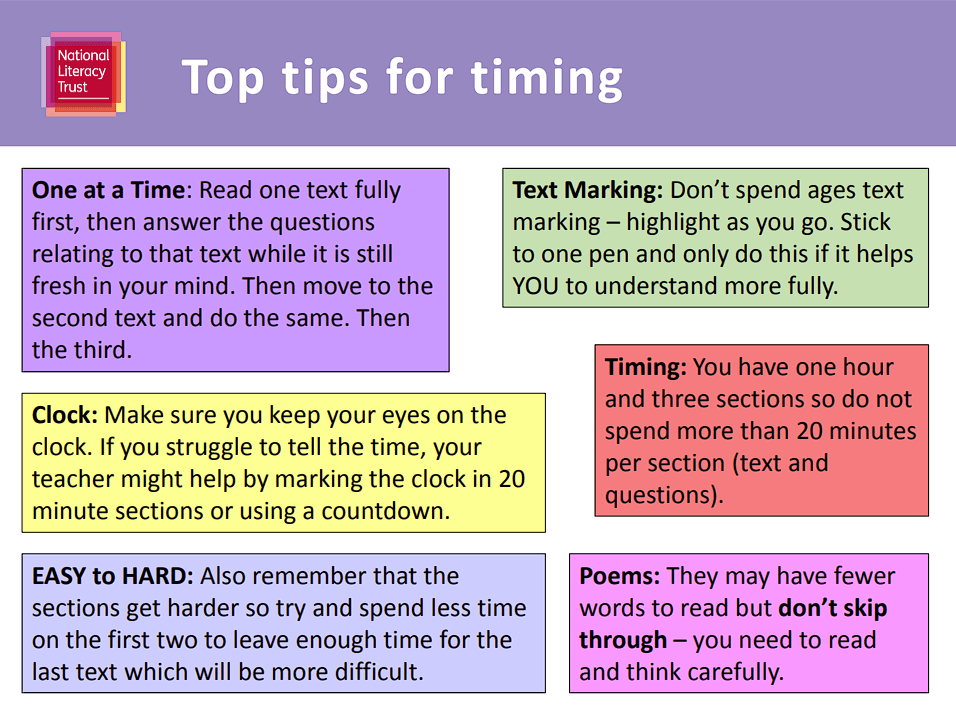

Reading paper revision tips

Use this revision guide PowerPoint from the National Literacy Trust to remind pupils of the key aspects of the reading paper before the big day.

English SATs preparation Year 6 advice

Make sure children get the scores they deserve with these last-minute and not-so-last-minute SATS checks from Shareen Wilkinson.

More English SATs preparation ideas

1. Tackling tough words

Teaching vocabulary skills in context is essential. Whilst we cannot predict the words that will appear on the test, we can give pupils quick strategies that will support them, whatever they encounter.

For example, take a classical text and replace certain words with nonsense words. Can the children think of plausible substitutions for your replacements? (I sometimes add capital letters to nonsense words to indicate they might be proper nouns.)

Pupils should be able to deduce what each word might be from the context.

2. Speed searches

Maintain a focus on scanning skills under timed conditions. Quick-fire activities, such as Where’s Wally or spot the difference, are perfect for continuing to develop retrieval skills before they are applied to more complex texts.

3. It’s not what ‘you’ think

It is crucial for pupils to recognise that all answers will be based on the test and not their own views.

Questions that contain the word ‘you’ are somewhat misleading. For example, ‘How can you tell…?’ ‘Give two impressions this gives you.’ Reinforce that evidence is found in the text.

4. Don’t repeat the question

This might seem like an obvious point, but it is crucial that pupils do not repeat the question stem in their answer – but rather explain it.

For example, if the question is ‘Why were the dodos curious and unafraid?’, it’s not unusual in instances like this for children to write something along the lines of, “Because they were unafraid”. This means they’ll miss out on a mark.

To avoid this, work on using synonyms and explaining answers.

5. Perfect punctuation

Accuracy is extremely important. The punctuation of direct speech will only be creditworthy if the closing punctuation is placed inside the final inverted commas.

In previous tests pupils have lost marks for inconsistencies such as mixed use of inverted commas (eg ‘ and “).

6. Read questions closely

‘Write a sentence using the word ‘point’ as a verb. Do not change the word.’

In questions like this, make sure children follow the instruction closely.

Pupils have lost marks in the past for adding a suffix (eg ‘pointed’ or ‘pointing’). They also lost marks for not starting with a capital letter and ending with appropriate punctuation.

7. Watch for stray capitals

If pupils are asked to write a sentence containing an adverb they may be penalised if they spell the adverb incorrectly or if they start the adverb with a capital letter in the middle of a sentence.

Don’t let your pupils miss out due to simple errors.

8. Avoid getting caught out

Prefixes, suffixes, verb forms and plurals must be spelt correctly.

One question in the 2016 grammar paper required pupils to change the word ‘caught’ to the present tense. The answer is ‘catch’, but even though pupils knew the answer, they lost marks for spelling ‘catch’ incorrectly.

Again, spelling does count within the grammar test – even though there is a separate spelling paper.

KS2 maths SATs resources and advice

The KS2 maths SATs test is split into the three papers – and it’s not easy to predict which topics will come up in each one.

Area and perimeter won’t show up in paper 1 (arithmetic) as this is purely a calculation paper. On paper 1, fractions questions will always involve fractions of amounts or multiplying or dividing fractions.

Papers 2 and 3 usually have questions in context. Measures, statistics and shape and space will only come up on these papers.

You can view a list of what can potentially be included in the papers on a government document called Mathematics Test Framework. This lists all the areas that could be tested – but they aren’t all included every year.

What past SATs data tells us

In this webinar from Third Space Learning, two former teachers share the highest impact SATs topics of 2025 using seven years of SATs papers and data from thousands of SATs revision sessions.

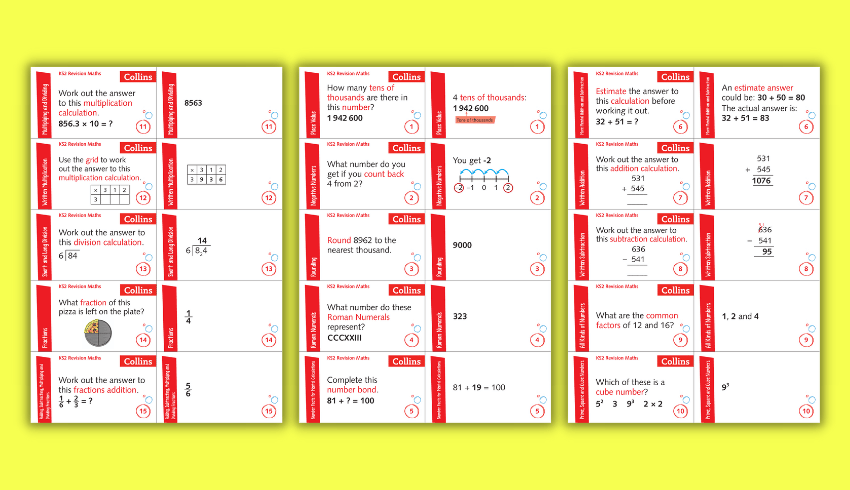

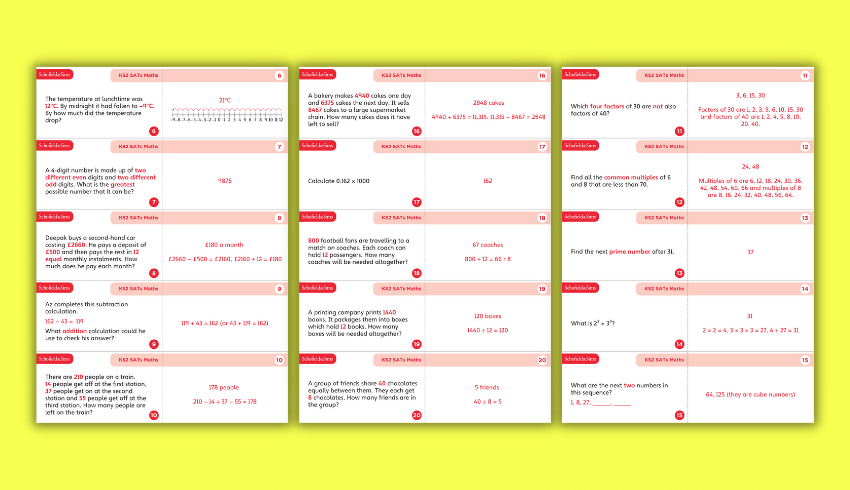

Maths flash cards

This free set of KS2 maths flashcards, created by Collins, will give Year 6 pupils lots of maths practice.

Maths SATs questions

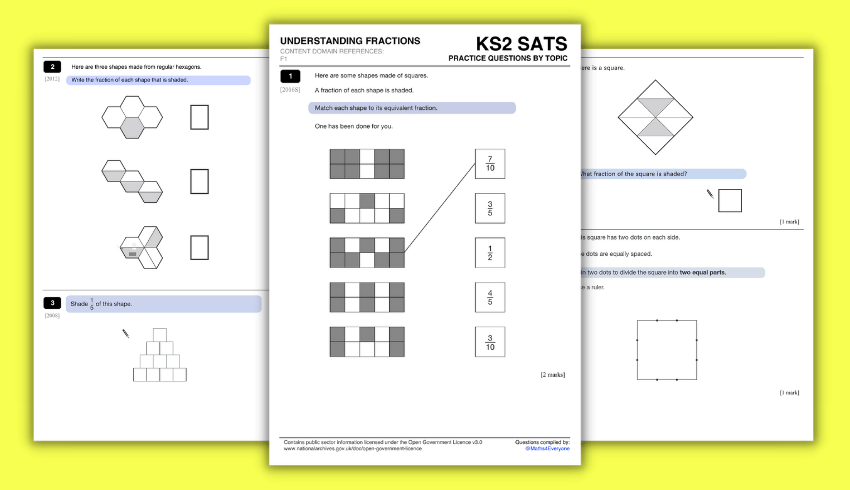

Fractions SATs questions

Using these free fractions SAT questions from experienced maths teacher David Morse will help to test and extend students’ understanding, as well as helping them to prepare for SATs.

You can print the eight-page PDF and turn it into an A4 or A5 booklet. You can also display the solutions on your whiteboard, making feedback more efficient.

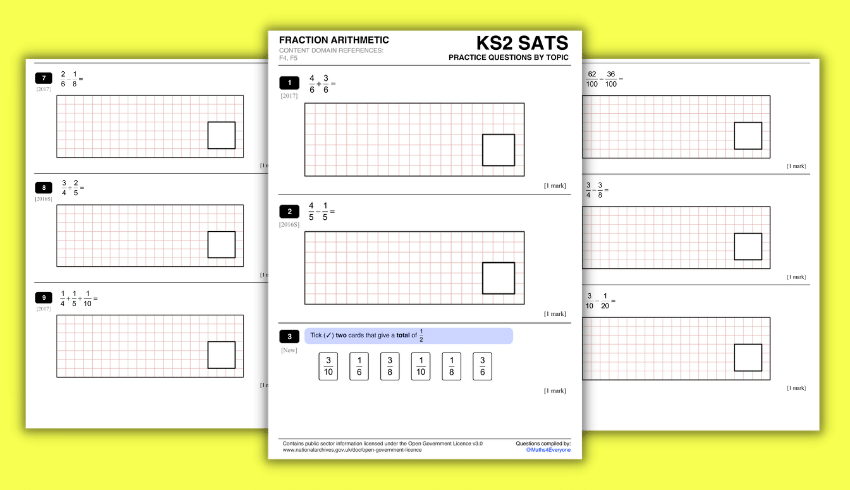

Fraction arithmetic questions

David Morse has also created this free fraction arithmetic questions pack for KS2 SATs practice. It’s a 12-page PDF featuring 32 questions for pupils to have a go at.

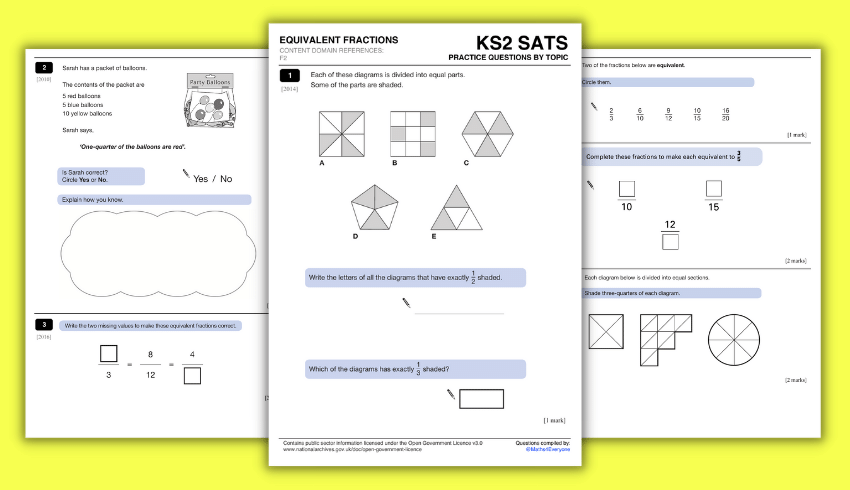

Equivalent fractions Year 6 questions

These free printable equivalent fractions Year 6 questions have fully-worked solutions which can be displayed on a whiteboard.

More KS2 maths worksheets

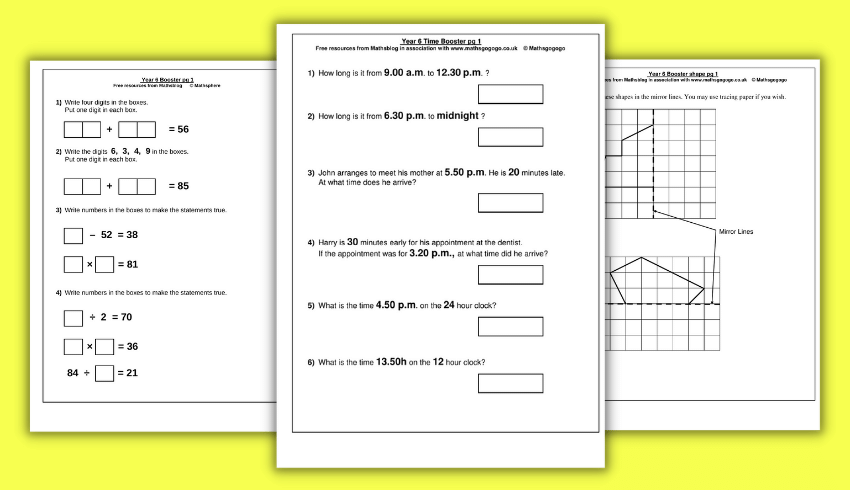

Maths Blog has a whole host of printable KS2 maths booster worksheets that pupils can do at school or at home. There are 14 PDFs for number-related questions, three for shape and four each for time and graphs.

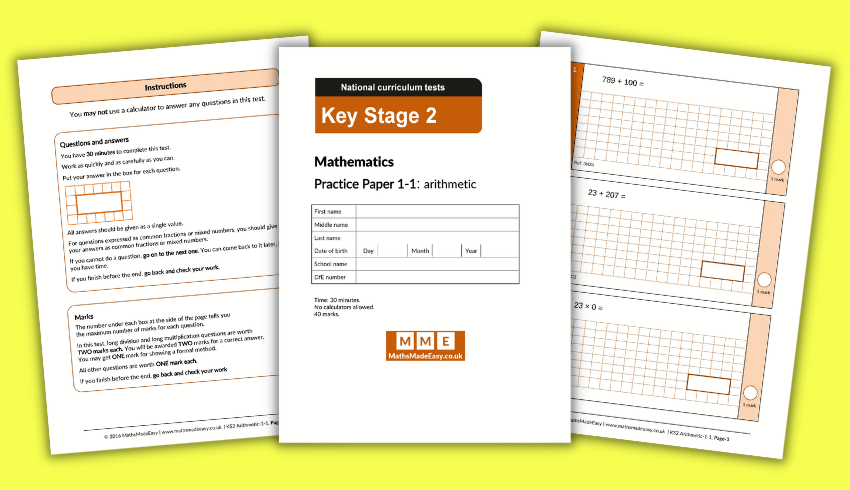

Head over to Maths Made Easy to find more KS2 SATs practice papers. There’s two for arithmetic and four for reasoning to try.

SATs questions linked to contents domain

Headteacher Mr T has created a free download laying out Year 6 SATs questions linked to the contents domain.

Free KS2 SATs online 10-minute tests

These CGP 10-Minute Tests are ideal for SATs revision in Year 6. There are six tests to choose from – three for maths and three for English.

All the answers are explained at the end of each test, so it’s easy to spot any areas that need a little extra work.

If you’re looking for an offline solution, these SATs 10-Minute Tests downloads from Schofield and Sims cover maths and English for both KS1 and KS2.

Here’s another couple of free online 10-minute tests to try, from STP Books. There’s one focusing on KS2 grammar and punctuation and another on KS2 spelling.

How to energise your SATs prep

Incorporating the following ideas into your strategy can keep children motivated in the lead-up to SATs week.

While it’s important to remember that SATs preparation may also require more focused, serious activities, mixing in fun and creative approaches helps to balance the hard work.

Escape room challenges

Turn your classroom into an ‘escape room’, where children must solve SATs-style questions to unlock each new challenge and progress to the next level of the game.

Set up different stations, each focusing on a topic such as decimals, prepositions or coordinates. Pupils work in teams to solve problems within a time limit. Each correct answer gives them a clue or code to unlock the next level.

This not only makes learning fun, but also helps children who may struggle with certain questions to feel less anxious.

Working in a team gives them the support they need, so they don’t feel pressured to figure out answers alone. It boosts their confidence as they help their group move forward to unlock the next question.

Leaderboards and power-ups

Set up a classroom leaderboard where children earn points for answering questions correctly, completing tasks, or hitting personal bests.

Keep things exciting by adding power-ups: for example, answering three questions in a row correctly could earn a hint token they can use later when they’re stuck on a tough question.

You could also offer speed boosts for completing tasks quickly or shield tokens to protect from losing points if they get a tricky question wrong.

Team battle

Challenge children to compete in small teams. Each team starts with a set number of ‘lives’ (points), and every time they answer a question incorrectly, they lose a life. The last team standing wins the game.

To keep it interesting, mix in different types of questions, such as quick-fire, multi-step, or creative problem-solving.

Trending

You could even let teams level up with bonuses like extra time or the opportunity to steal a point from another team.

Challenge tournaments

Create a buzz in your classroom by setting pupils a series of timed challenges – think of it as a mini SATs Olympics.

Set up stations with tasks like SATs-style reasoning, problem-solving and reading comprehension questions. Children race to complete each task correctly, working in small teams.

You can award medals, certificates, or fun rewards at the end of the tournament. This will bring some fun and healthy competition, all while familiarising children with the main types of SATs question styles.

Superhero academy

Develop SATs Mission Cards, with a mix of individual and group tasks. Missions could involve solving reasoning problems or helping a peer with a reading comprehension exercise.

Each completed mission earns ‘superpowers’ like badges or points. You can even allow children to customise their superhero identity by earning powers in specific subjects like Maths Master, Grammar Guru, or Spelling Sorcerer.

Finish the academy with a SATs Superhero graduation, where children receive certificates and their superhero personas are revealed.

Wheel of fortune

Ask children to spin a wheel to determine which type of SATs question they’ll face – reasoning, arithmetic, grammar, punctuation, spelling, or reading comprehension.

To add a challenge, include bonus sections like double points for a correct answer or a lightning round where pupils must answer as many questions as possible in 60 seconds.

The random element adds excitement and keeps children on their toes.

Get moving

Let’s bring life into SATs prep by getting our energetic Year 6s moving! Try revision relays outside on a dry day, where children race between stations to answer questions or solve problems.

Short brain breaks, with stretching or mindfulness can also recharge children and boost concentration.

Rachael Ede, a former Year 6 teacher, founded SATs Boot Camp to help teachers and students get ready for SATs with less stress.

How to stop SATs prep taking over

Preparing for SATs doesn’t need to take over the whole of Year 6, says KS2 teacher Sarah Farrell. Dipping in little and often is much easier to digest…

While we don’t want SATs to dominate our children’s last year of school, we do want them to feel prepared and to be as successful as they can.

While it can be tempting to restrict a Year 6 timetable to be as SATs-focused as possible over the next few weeks, there are better ways to make sure both you and your class feel ready by the time May comes around.

And remember: SATs are a whole-school responsibility. The tests cover content from the whole of Key Stage 2, so it is not solely down to you to get the children to achieve 100 per cent.

Practise

Rather than packing your timetable with lots of extra full-length maths and reading lessons, consider shorter, sharper sessions.

A ten-minute speed-reading practice or quick refresh on multiplying pairs of fractions is likely to be more effective than replacing an afternoon of wider curriculum lessons.

You could also include activities such as online quizzes and games to keep it interesting and avoid too much repetitive written practice.

Target

Identify any whole-class, group or individual areas of weakness that your class may have and build in time to directly target them.

If the majority of the class finds it tricky to calculate a fraction of an amount, for example, make that a part of the beginning of every maths lesson for a week.

For small group or individual areas, providing some targeted questions as morning work can close gaps and help children to feel more confident.

Model

Modelling how to approach the papers is a great way to show children what to expect and how to avoid common pitfalls.

For example, you might display a question from the reading test and model your thinking aloud like this:

“The question says that I need to look at paragraph four, so I’m going to find paragraph four first of all. It then asks me to identify how Ben knew there was a dolphin nearby before he could see it, so I’m looking for clues in the text that might relate to his other senses or maybe to the water rippling.

“I’m then going to check that the evidence I’ve found is definitely in paragraph four, as that’s where I was told to look. “It’s asked me for two examples, so I’m going to make sure I write two pieces of evidence down.”

While this may seem like a lot, explaining your thinking helps children know how to approach similar questions.

With maths questions, model underlining key information, drawing bar models or diagrams, or writing out the steps you’ll take when answering a reasoning question.

Discuss

When presented with a wordy problem with several large numbers, some children may panic and not try it at all, or just add all the numbers together and hope for the best.

A great way to recap key facts and help children to develop their ability to answer tricky questions is to initially hide key information.

For example, display a multi-step reasoning problem with the numbers covered. Ask children to discuss in pairs how they might approach the question, then share strategies together.

As a class, agree on a set of steps that will be completed when the numbers are shown. When you have a plan, share the numbers and set the class off to complete the question.

The benefit of this approach is that it slows children down a bit and encourages them to really think about what’s being asked in order to help them to select the right operations needed.

Find

Children love finding mistakes! Present them with some questions that you have completed badly and task the children with finding out what mistakes you have made.

Try to use mistakes that your class commonly make themselves, as this is a great way to tackle persistent errors. You could then create a class list of common mistakes to prevent them from making them again when they next come to take a test.

Sarah Farrell is a KS2 teacher in Bristol who makes and shares resources online.

SATs criticisms and controversies

SKIP TO A SECTION

2022 reading paper and 11+ crossover

In 2022, one anonymous primary teacher argued that the SATs reading paper favoured the already advantaged, because a section had been on the 11+ paper earlier in the academic year...

At the end of 2022’s English reading SATs paper, something strange happened: as the children filed out of the hall, instead of the usual ashen-faced signs of exhaustion and stress, a good number came out positively beaming.

“We’ve done this before!” they said. “That was so easy!”

I had never seen a reaction like that to a reading SATs paper, the most gruelling of all the papers. I had just been invigilating a small group of children who either had extra time or who were prone to panic; none of them had found it easy.

I asked these jubilant pupils what they were talking about and was told a section had been on the 11+ paper they did earlier in the academic year. The very same extract from the very same book.

“I was told a section had been on the 11+ paper they did earlier in the academic year”

A Traveller in Time

The controversy revolved around the third and final piece that children had to read and answer questions on. Typically, this is both the hardest piece to read and comes at a point in the exam where pupils’ stamina is often flagging.

In this case, it was an extract from a 1939 text called A Traveller in Time by Alison Uttley.

In the extract, time seems to stand still as a girl passes by a mysterious lady in old-fashioned clothing on a staircase. There is a greeting smile between the two before the girl turns and follows her, only to find she has disappeared.

The text makes perfect sense if you are forearmed – as many of my children were – with the knowledge that the lady comes from the Elizabethan era and that we are in a time-slip story.

Without this knowledge, as was the case for most of the children who did not take the 11+, it would be easy to read this story literally and miss the symbolic value of much of the detail – particularly if they were struggling to stay on time.

Notifying the STA

When I notified the Standards and Testing Agency (STA), they argued that they ‘cannot entirely mitigate against pupils having read certain texts, or against them being used by other organisations.’

They also argued that checking the texts against other tests would be ‘impractical and expensive.’

“They argued that they ‘cannot entirely mitigate against pupils have read certain texts'”

Of course, if you choose to use a real and readily available text in the exam there is always a chance children would have encountered it before. It would therefore make sense for them to write the texts from scratch (or at least take a cursory glance at the biggest test our Y6 children had ever faced).

With no SATs in 2020 or 2021 due to Covid, the STA had three years to get these tests right and they did not succeed.

It failed at the single most important part of its job. After all, what is the point in standardised testing other than to provide a fair and impartial measure of the children’s abilities?

To allow a situation where a particular (often privileged) demographic of the cohort is at an advantage seems to be allowing, and possibly encouraging, bias.

2021 SATs cancelled

In late 2020, Matthew Kleiner-Mann, leader of of Ivy Learning Trust (@ivy_trust), argued that SATs should not be scrapped. In January 2021 the government did indeed go on to cancel 2021 SATs, recognising that the tests would be “an additional burden on schools” during Covid…

While teachers hate SATs (and parents love them), the vast majority of children simply accept them as part of school life. It’s just something they do at the end of school; a rite of passage like the class photo or school disco.

The prospect of them not being there is another example of how Covid-19 has robbed them of normality.

After a tumultuous few months, which have seen their lives being turned upside down, children are really happy to be back at school. They’re glad of their routine, of learning, of normal life.

So when I received an email asking me, along with dozens of other school leaders, to sign a petition to stop SATs going ahead in 2021, I wondered why people felt so strongly about it.

Is it about Covid-19, or simply a longstanding dislike of SATs? Because, whether you agree with SATs or not, now is not the right time for this argument.

Additional stress

First let’s look at the possible effect of SATs on the children taking them. Some leaders have argued that children may feel additional and unnecessary stress because of these tests on top of the ongoing pressures of Covid-19.

However, if children are feeling under pressure about SATs, then their schools are doing it wrong. This ‘cramming’ for tests should have been wiped out years ago.

“This ‘cramming’ for tests should have been wiped out years ago”

Some children have undoubtedly had a difficult time during lockdown and will need additional support but this should be dealt with individually, not by taking SATs away from everyone.

And fundamentally, SATs aren’t for children. They don’t – or at least they shouldn’t – care about the results.

They’re not like GCSEs or A-levels that have to go on your CV permanently. You can’t ‘fail’ your SATs and they don’t affect your future.

SATs are about understanding progress. They help parents to know if their child is doing OK, if they’re ready for secondary school and if they need extra support.

They help primary schools see how pupils are progressing and secondary schools understand where children are at.

Accountability

Schools should be accountable for the progress children have made and we need to know that result. You’re only able to allocate resources if you understand where the gaps are.

If we don’t find out whether a child is ready for secondary school or not, and what additional support they need, we’re doing them a huge disservice.

“I don’t believe SATs are a problem in themselves”

I don’t believe SATs are a problem in themselves. They give a good indication of how a child is progressing through their education, benchmarked nationally.

Level playing field

The primary concern now is that the same level of accountability will be applied to all schools, when they’ve had very different experiences during Covid-19 based on factors beyond their control. This includes the communities they serve, digital poverty, local outbreaks or lockdowns.

Because of these factors, it’s difficult to ensure a level playing field and schools may feel unfairly judged.

This absolutely needs to be acknowledged and addressed, but not by cancelling SATs altogether. Instead, there should be a deeper understanding and acceptance that not all schools have had the same experience in the 18 months leading up to the tests.

We need to know where a Y6 child is at, but the school shouldn’t be punished if pupils haven’t progressed as expected because of factors beyond their control.

SATs should go ahead, but with the proviso that future judgements of the school take into account the actual experiences of children during lockdown, what schools did to support their communities with home learning, and progress made in closing any gaps since schools have reopened fully.