Getting tough on pupil behaviour won’t work

We don’t need a crack down or reasonable force – nurturing relationship policies and a therapeutic approach will get better results, says Jules Daulby…

- by Jules Daulby

Behaviour is in the news. Recently, a leaked document came from the DfE suggesting that reasonable force would be encouraged to remove children who were a distraction in class.

Ofsted has introduced a new behaviour strand in their inspection process. And due to the rise in exclusions, the DfE has announced funding for more free schools to deal with the problem of children out of mainstream schools.

Let’s first unpick behaviour. There is a sliding scale from low-level disruption to violence or abuse.

For less-serious incidents, the pastoral staff in schools would likely manage but as a child’s behaviours escalate, other agencies and the school’s SENCo should be involved – the first questions being: are there any underlying causes for such behaviour?

The old label before the 2014 SEND reforms was called emotional and behavioural difficulties (EBD).

It is now known that behaviour is a physical symptom of deeper, underlying needs such as mental health and adverse childhood experiences (ACE) so EBD was replaced with social, emotional and mental health (SEMH).

This is a SEND category and includes those children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

These children are among the most at risk of exclusion alongside those with speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) such as autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) and developmental language disorder (DLD) – so many acronyms!

“Low-level behaviour difficulties are not a SEN, they are just naughty children trying it on,” is a common refrain and furthermore, many children with SEND do not have behaviour difficulties.

This is where the conflict lies.

“All behaviour is communication” is not a term favoured by Tom Bennett, the DfE’s behaviour tsar who leads a £10m government initiative on a behaviour ‘crack down’. He wants to create behaviour hubs where schools who are successful will support others requiring help.

Bennett believes children need rules and boundaries, routines and “positive and compassionate social norms” – not a million miles away from those who believe in a therapeutic behaviour policy.

So where is the difference?

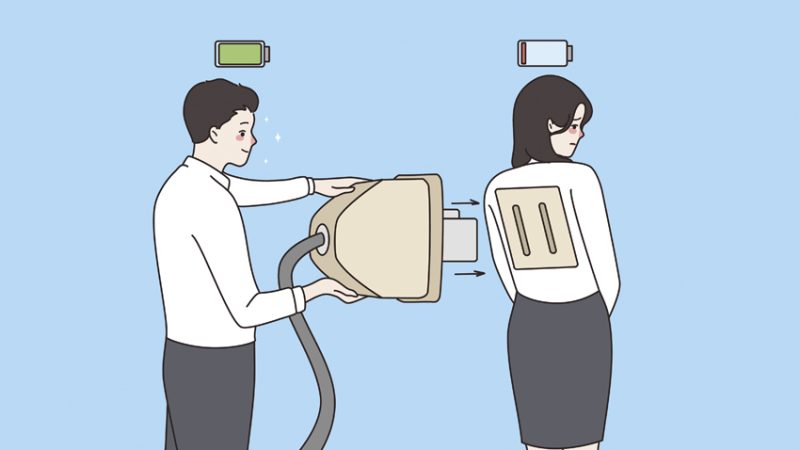

Crudely speaking, there is a behaviourist approach and a therapeutic approach (ACE aware and trauma informed schools are examples). Some schools have ditched the term ‘behaviour management policy’ for ‘relationships’, already shifting the narrative.

Trauma in childhood is likely to impact on learning but this can be negated with positive behaviour or therapeutic approaches. We need to ask ourselves, are we growing good citizens or simply instilling a fear of punishment? Are children making good choices for all the right reasons?

Putting a child in an isolation booth might work for some as a short, sharp shock, but the most needy in our schools will tend to end up returning to the booth over and over again, showing that this form of punishment simply does not work in the long term.

It brings with it a sense to the child that they do not belong, and the longer they stay in booths, the harder it will be for them to return to the classroom.

This is another reason why I believe we must separate out the low-level behaviours for the majority of children from the fewer more vulnerable children.

They may be few in number but high in cost, and for them, a nurturing environment where support is “just enough, soon enough” requires far more sensitive approaches.

Another tricky area in schools is restraint. There are many who will not use restraint, preferring holds and blocking, using strategies such as the STEPS approach.

Others continue to use restraint as a last resort, with strategies such as Team Teach.

There is, however, a postcode lottery on training for all these approaches and the worst-case scenario is a tendency to resort straight to restraint rather than using the stepped approach which is advised.

The use of nurturing relationship policies does not mean that schools are ‘soft on behaviour’. As with the DfE’s behaviour ‘crack down’, no one is arguing that routines, boundaries and high expectations should not be the norm.

However, there must be flex in a system to ensure our most vulnerable children are being supported in a kind environment that is curious about behaviours and why they happen.

Professor Rachel Lofthouse from Leeds Beckett University writes: “The answer is not stricter school behaviour interventions, but a growing understanding by teachers of how to engage in co-regulation with their pupils.

Research also tells us that where teachers have greater empathy for pupils, the number of exclusions is reduced.”

How Ofsted’s behaviour inspection process and the government’s crack down on behaviour goes, time will tell. But it seems at odds with many schools who are finding a therapeutic response more successful.

Jules Daulby is an education consultant specialising in inclusion and literacy. Follow her on Twitter at @julesdaulby.