Educational research – where to look and what to ask

There is a lot of educational research around, but how do you know what's useful and what's not? Dr Julian Grenier shares his advice…

I vividly remember the first time I went to a conference about using research in the classroom. It was the early 2000s. The conference was in a huge, grand hall in Islington with around 500 people.

There were stalls with piles of books and leaflets about brain science. After a frankly dizzying set of PowerPoint slides and videos showing how synapses fire in brains and make connections, we were all told to stand up.

“Right,” said the charismatic course leader. “We’re going to activate your brains now. First, you have to hydrate your brain. That’s why we’ve given everyone a bottle of water.”

After a quick swig, we had to follow him making a slightly strange set of movements. We rubbed our stomachs, did something to ‘activate the brain button’, and so on.

We were being trained to follow a research-informed primary programme called ‘Brain Gym’. It was an impressive, entertaining and enjoyable day of training, with one flaw.

It turns out that Brain Gym was nonsense. It had never been rigorously evaluated. The science behind it was, at best, dubious.

Brain Gym has been debunked, but similar fads continue to get attention in schools. There is always a lot of noise about the latest innovations.

So, you feel under pressure to keep up and try out the latest thing you’ve seen online, or heard about from the school up the road. As a school leader, I get at least 50 emails a week from companies and private educational consultants.

They are all trying to sell me their latest products or services. I ignore them.

I am not suggesting that you should just stick to your old ways. There is always room for improvement in every classroom. But before you try anything new out, here are a few tips.

What’s your problem?

Firstly, think hard about the problems you are facing in your classroom. It is all too easy to get sucked into trying out a solution to a problem you don’t have.

For example, it might be important to think about the barriers to learning that some of your pupils face. If every year there is a group of pupils who don’t progress well in their reading, then that’s your problem.

You probably do not need a whole new approach to teaching English that will take up a huge amount of time and energy to put into practice.

You might need a well-evidenced intervention that you or your TA can be trained to deliver to help a small group of pupils catch up with the rest.

Demand evidence

Next, you might spend some time exploring the evidence about catch-up reading programmes. You can safely ignore much of the ‘research’ that people try to sell you, or that gets liked and shared on social media. We should have a high bar for ‘evidence’ in education.

Our pupils’ life chances depend on the education we give them. So you should think about evidence like a doctor would. That means asking some questions.

How robust is the research behind the approach? Has it been tried in several schools, at least some of which are similar to your own? Was there a comparison group of pupils who did not get the new approach? Was there a significant difference in outcomes between the two groups?

Even when the evidence looks strong, you should remain cautious. You might consider the ‘costs’ of the new approach. How much training will be involved? Will you need to buy new equipment? How much of your time will be spent in extra planning or assessment work?

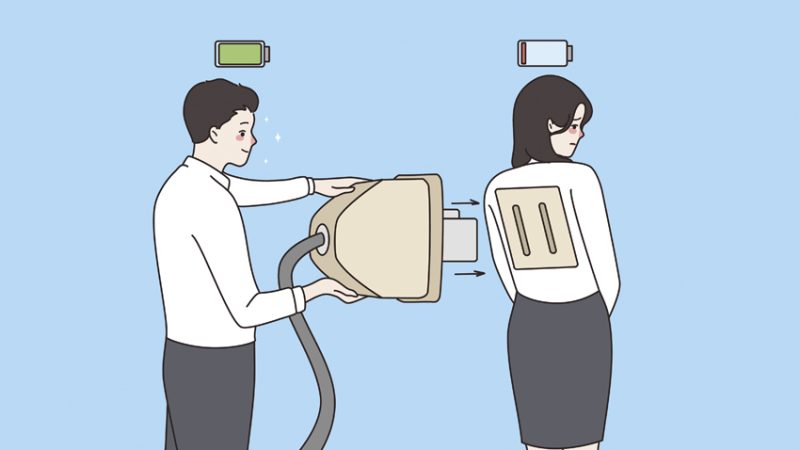

Teachers are always hard-pressed. If you have to spend more time doing new things, then you will have less time and energy for other things.

But, the things you stop doing may be even more important for your pupils’ progress than the new approach you are bringing in.

Be practical

My final note of caution is that you should make sure there is enough help for you to put the new approach into action. It is hard to manage change well.

I am sure almost everyone reading this has experienced some big, shiny new approach that launched with a bang in September, only to fizzle out slowly during the long, dark days of January and February.

A year later and it’s forgotten. I have made this mistake countless times as a school leader.

I am not against change. I am merely cautious about checking everything out before making big commitments of time, money and teacher energy. Before you go into the woods of educational research, get the best guide you can.

Talk it out

School culture is also important. We should be talking about things that go wrong in our classes, so we can learn from them, rather than trying to cover things up.

Our schools need to have a ‘growth environment’ so we can get better at putting the evidence into action over the course of our careers. It is heartening to see that the new Early Career Framework has a strong focus on evidence-informed practice.

By giving new teachers a two-year period to consolidate and develop their professional skills and knowledge, it allows for deeper thinking about evidence-informed practice.

Teaching will never be an entirely research-based profession. We should not seek programmes with manuals to follow dutifully, even if they are based on research.

Great teaching is all about a set of complex professional skills. You need to know your pupils and their families. You need to develop the right relationships.

You need to have an instinct for when something is going wrong, or for when pupils might need more help than you expected. Schools are complex, messy places.

That’s why Professor Dylan Wiliam famously stated that we should stop looking for ‘magic bullets’ to solve our classroom problems. He argued that ‘“What works?” is rarely the right question, because everything works somewhere, and nothing works everywhere.

In education, the right question is, “Under what conditions does this work?”

Dr Julian Grenier is director of East London Research School and headteacher of Sheringham Nursery School and Children’s Centre. Find him on Twitter at @juliangrenier.