Creative writing prompts – Best activities and resources for KS1 and KS2 English

Fed up of reading 'and then…', 'and then…' in your children's writing? Try these story starters, structures, worksheets and other fun writing prompt resources for primary pupils…

- by Laura Dobson

- Deputy headteacher and former adviser at Inspire Primary English

What is creative writing?

According to the Cambridge English Dictionary, ‘creative’ is ‘producing or using original and unusual ideas’, yet I would argue that in writing there’s no such thing as an original idea – all stories are reincarnations of ones that have gone before.

As writers we learn to be expert magpies – selecting the shiny words, phrases and ideas from other stories and taking them for our own.

Interestingly, the primary national curriculum does not mention creative writing or writing for pleasure at all and is focused on the skill of writing.

Therefore, if writing creatively and for pleasure is important in your school, it must be woven into your vision for English.

“Interestingly, the Primary National Curriculum does not mention creative writing or writing for pleasure at all”

Creative writing in primary schools can be broken into two parts:

- writing with choice and freedom

- developing story writing

Writing with choice and freedom allows children to write about what interests and inspires them.

Developing story writing provides children with the skills they need to write creatively. In primary schools this is often taught in a very structured way and, particularly in the formative years, can lack opportunities for children to be creative.

Children are often told to retell a story in their own words or tweak a detail such as the setting or the main character.

Below you’ll find plenty of creative writing prompts, suggestions and resources to help develop both writing for choice and freedom and developing story writing in your classroom.

How to develop opportunities for writing with choice and freedom

Here’s an interesting question to consider: if the curriculum disappeared but children still had the skills to write, would they?

I believe so – they’d still have ideas they wanted to convey and stories they wanted to share.

One of my children enjoys writing and the other is more reluctant to mark make when asked to, but both choose to write. They write notes for friends, song lyrics, stories and even business plans.

So how can we develop opportunities to write with choice and freedom in our classrooms?

Early Years classrooms are full of opportunities for children to write about what interests them, but it’s a rarer sight in KS1 and 2.

Ask children what they want to write about

Reading for pleasure has quite rightly been prioritised in schools and the impact is clear. Many of the wonderful ideas from The Open University’s Reading For Pleasure site can be used and adapted for writing too.

For example, ask children to create a ‘writing river’ where they record the writing they choose to do across a week.

If pupils like writing about a specific thing, consider creating a short burst writing activity linked to this. The below Harry Potter creative writing activity, where children create a new character and write a paragraph about them, is an example of this approach.

If you have a spare 20 minutes, listen to the below conversation with Lucy and Jonathan from HeadteacherChat and Alex from LinkyThinks. They discuss the importance of knowing about children’s interests but also about being a writer yourself.

Plan in time to pursue personal writing projects

There are lots of fantastic ideas for developing writing for pleasure in your classrooms on The Writing For Pleasure Centre’s website.

One suggestion is assigning time to pursue personal writing projects. The Meadows Primary School in Madeley Heath, Staffordshire, does this termly and provides scaffolds for children who may find the choice daunting.

Give children a choice about writing implements and paper

Sometimes the fun is in the novelty. Are there opportunities within your week to give pupils some choices about the materials they use? Ideas could include:

- little notebooks

- post-its

- a roll of paper

- chalk

- felt tip pens

- gel pens

Write for real audiences

This is a great way to develop children’s motivation to write and is easy to do.

It could be a blog, a class newsletter or pen pals. Look around in your community for opportunities to write – the local supermarket, a nearby nursing home or the library are often all good starting points.

Have a go yourself

The most successful teachers of story writing write fiction themselves.

Many adults do not write creatively and trying to teach something you have not done yourself in a long time can be difficult. By having a go you can identify the areas of difficulty alongside the thought processes required.

Treat every child as an author

Time is always a premium in the classroom but equally, we’re all fully aware of the impact of verbal feedback.

One-to-one writing conferences have gained in popularity in primary classrooms and it’s well-worth giving these a go if you haven’t already.

Set aside time to speak to each child about the writing they’re currently constructing. Discuss what’s going well and what they could develop.

If possible, timetable these one-to-one discussions with the whole class throughout the year (ideally more often, if possible).

Creative writing resources for the classroom

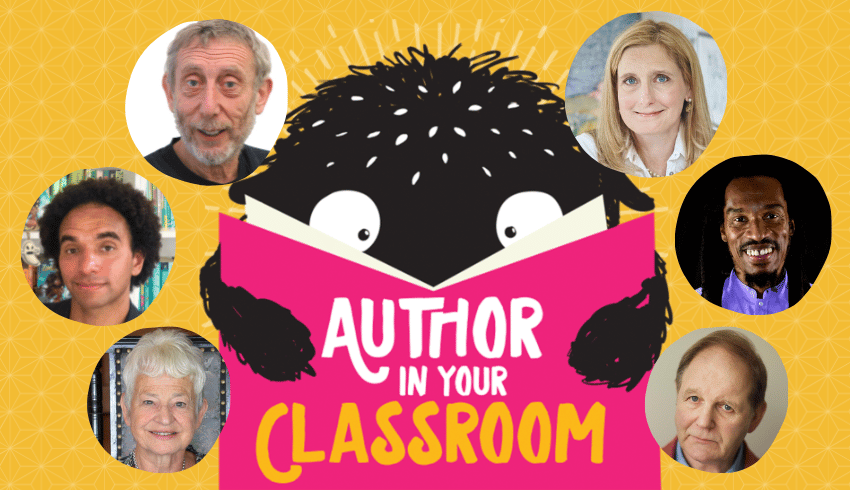

Free KS2 virtual visit and resources

Bring best-selling children’s authors directly into your classroom with Author In Your Classroom. It’s a brilliant free podcast series made especially for schools, and there’s loads of free resources to download too.

More than 20 authors have recorded episodes so far, including:

- Sir Michael Morpurgo

- Dame Jacqueline Wilson

- Michael Rosen

- Joseph Coelho

- Lauren Child

- Frank Cottrell-Boyce

- Benjamin Zephaniah

- Cressida Cowell

- Robin Stevens

- Liz Pichon

Creative writing exercises

Use these inspiring writing templates from Rachel Clarke to inspire pupils who find it difficult to get their thoughts down on the page. The structured creative writing prompts and activities, which range from writing a ‘through the portal story‘ to a character creation activity that involves making your own Top Trumps style cards, will help inexperienced writers to get started.

Prompts for creative writing

This free PDF features a range of classroom games, ideas and prompts for creative writing from The National Literacy Trust. The activities can be completed independently, in pairs or in small groups. They’re perfect for National Writing Day.

Create confident writers

Use this inspiring KS2 lesson plan to help children write creatively with confidence. It focuses on eliminating the pressure of writing and turning writing tasks into fun games.

Storyboard templates and story structures

Whether it’s short stories, comic strips or filmmaking, every tale needs the right structure to be told well. This storyboard template resource will help your children develop the skills required to add that foundation to their creative writing.

Ten-minute activities

The idea of fitting another thing into the school day can feel overwhelming, so start with small creative writing activities once a fortnight. Below are a few ideas that have endless possibilities.

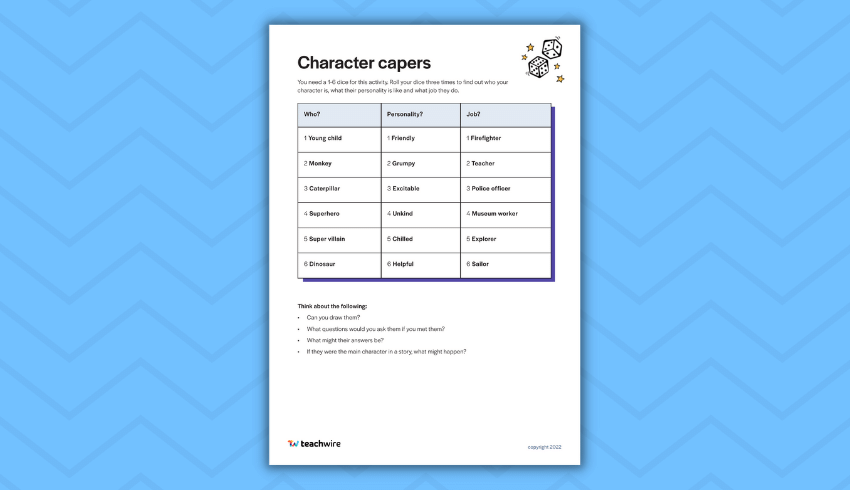

Character capers

You need a 1-6 dice for this activity. Roll it three to find out who your character is, what their personality is and what job they do, then think about the following:

- Can you draw them?

- What questions would you ask them if you met them?

- What might their answers be?

- If they were the main character in a story, what might happen?

Download our character capers worksheet.

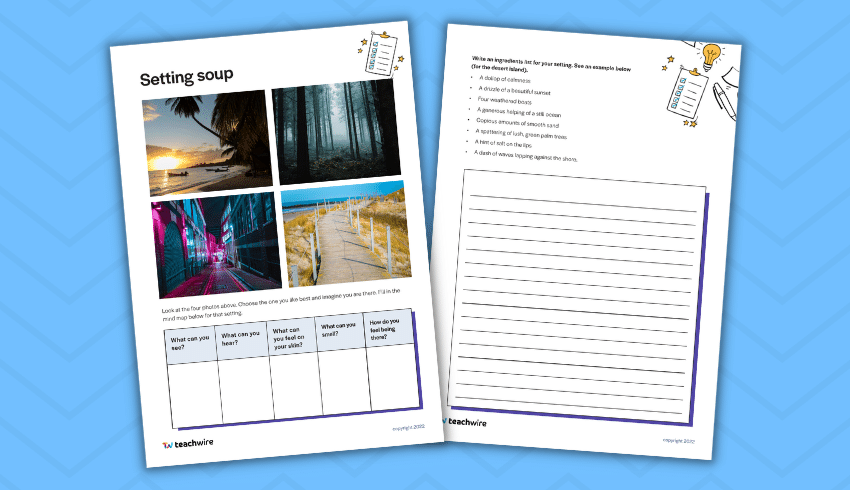

Setting soup

In this activity pupils Look at the four photos and fill in a mind map for one of the settings, focusing on what they’d see, hear, feel, smell and feel in that location. They then write an ingredients list for their setting, such as:

- A dollop of calmness

- A drizzle of a beautiful sunset

- A generous helping of a still ocean

- Copious amounts of smooth sand

- A spattering of lush, green palm trees

Download our setting soup worksheet.

Use consequences to generate story ideas

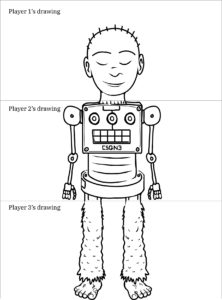

Start with a game of drawing consequences – this is a great way of building a new character.

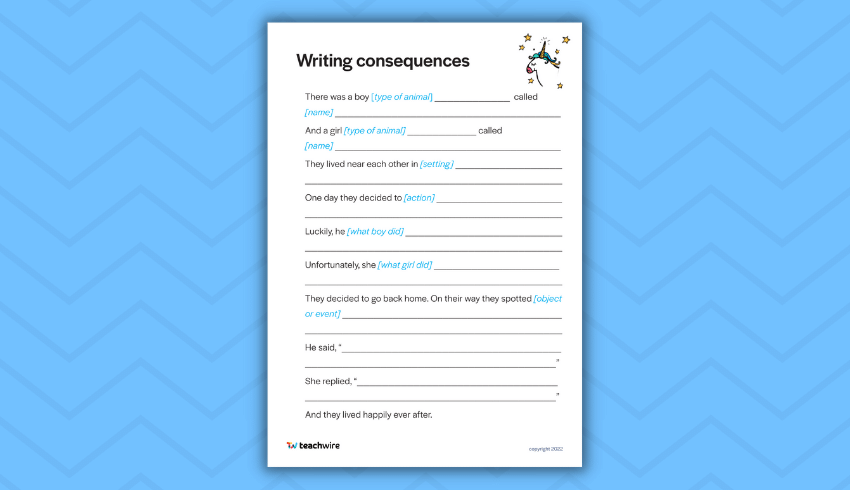

Next, play a similar game but write a story. Here’s an example. Download our free writing consequences template to get started.

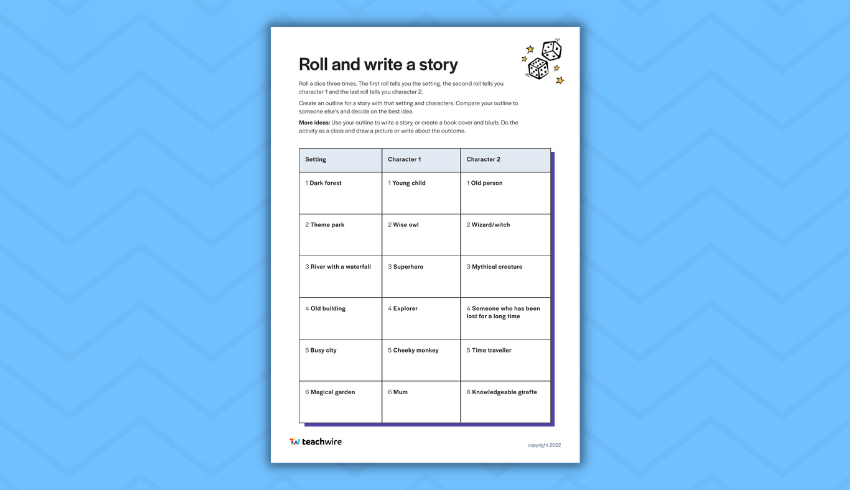

Roll and write a story

For this quick activity, children roll a dice three times to choose a setting and two characters – for example, a theme park, an explorer and a mythical creature. They then use the results to create an outline for a story.

Got more than ten minutes? Use the outline to write a complete story. Alternatively, use the results to create a book cover and blurb or, with a younger group of children, do the activity as a class then draw or write about the outcome.

Download our roll and write a story worksheet.

Scavenger hunt

Give children something to hide and tell them they have to write five clues in pairs, taking another pair from one clue to the next until the 5th clue leads them to the hidden item.

For a challenge, the clues could be riddles.

Pen pals

Set up pen pals. This might be with children in another country or school, or it could simply be with another class.

What do pupils want to say or share? It might be a letter, but it could be a comic strip, poem or pop-up book.

Authorfy

You need a log-in to access Authorfy’s content but it’s free. The website is crammed with every children’s author imaginable, talking about their books and inspirations and setting writing challenges. It’s a great tool to inspire and enthuse.

Oxford Owl

There are lots of great resources and videos on Oxford Owl which are free to access and will provide children with quick bursts of creativity.

Creative writing ideas for KS2

This free Pie Corbett Ultimate KS2 fiction collection is packed with original short stories from the man himself, and a selection of teaching resources he’s created to accompany each one.

Each creative writing activity will help every young writer get their creative juices flowing and overcome writer’s block.

Creative writing prompts

WAGOLL text types

Support pupils when writing across a whole range of text types and genres with these engaging writing packs from Plazoom, differentiated for KS1, LKS2 and UKS2.

They feature:

- model texts (demonstrating WAGOLL for learners)

- word mats

- worksheets

- planning guides

- writing templates

- themed paper

Each one focuses on a particular kind of text, encouraging children to make appropriate vocabulary, register and layout choices, and produce the very best writing of which they are capable, which can be used for evidence of progress.

If you teach KS2, start off by exploring fairy tales with a twist, or choose from 50+ other options.

Scaffolds and plot types

A great way to support children with planning stories with structures, this creative writing scaffolds and plot types resource pack contains five story summaries, each covering a different plot type, which they can use as a story idea.

It has often been suggested that there are only seven basic plots a story can use, and here you’ll find text summaries for five of these:

- Overcoming the monster

- Rags to riches

- The quest

- Voyage and return

- Rebirth

After familiarising themselves with these texts, children can adapt and change these stories to create tales of their own.

Use story starters

If some children still need a bit of a push in the right direction, check out our 6 superb story starters to develop creative writing skills. This list features a range of free story starter resources, including animations (like the one above) and even the odd iguana…

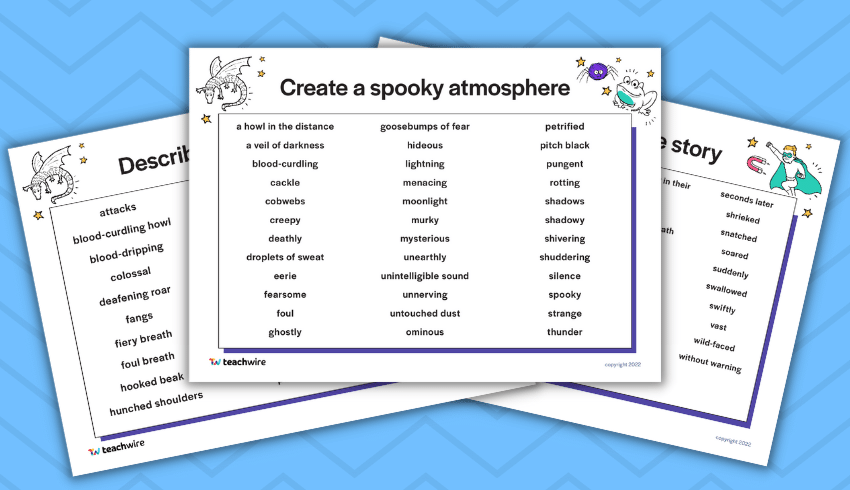

Use word mats to inspire

Help pupils to write independently by providing them with helpful vocabulary sheets that they can pick and choose from when doing their own creative writing.

Download our free creative writing word mats here, including:

- Create a spooky atmosphere

- Write an adventure story

- Describe a character’s appearance

- Describe a character’s personality

- Describe how a character moves

- Describe how a character speaks

- Describe a mythical beast

Websites to inspire reluctant writers

I use this Breaking News picture generator in class to stimulate writing of news scripts, then film the pupils reading their script as newscasters.

Classtools also has this amazingly realistic Facebook page creator. Use it to create profile pages for historical figures. You’ll be amazed how much effort pupils put in to creating a ‘Fakebook’ page compared to what they would have done if they’d have been writing a plain biography.

Fotojet has an excellent magazine generator that allows your photo to be placed on actual magazine titles, such as Time and Rolling Stone. Big Huge Labs will convert a photograph into a printable magazine cover.

Pulp-O-Mizer is especially useful when teaching the science fiction genre. You can generate a series of fabulous 1950s pulp-inspired book covers which look the part and are highly customisable, allowing you to change the title, text, colour and illustrations to produce a very professional-looking cover.

Instead of creating boring drawer labels in Word, why not use a Star Wars or Harry Potter font instead? Let children generate their own personalised name tags using some of the typefaces from famous films, bands or brands.

Julian Wood is a deputy headteacher in a Sheffield primary school, a CAS Master Computer Teacher and a Microsoft Innovative Educator.

Creative writing pictures

Pobble 365

Using images as writing prompts is nothing new, but it’s fun and effective.

Pobble 365 has an inspiring photo for every day of the year. These are great inspiration for ten-minute free writing activities. You need to log in to Pobble but access to Pobble 365 (the pictures) is free.

Choose two pictures as prompts (you can access every picture for the year in the calendar) or provide children with a range of starter prompts.

For example, with the photo above you might ask children to complete one of the following activities:

- Continue the story using the story starters on Pobble.

- Write down what your dream day would include.

- Create a superhero called Dolphin Dude.

- If you didn’t need to breath when swimming underwater, what would you do? Write about your dream day. It might include rivers, lakes, swimming pools, the seas or oceans.

- If you had a super power, what would it be and why?

The Literacy Shed

Website The Literacy Shed has a page dedicated to interesting pictures for creative writing. There are winter scenes, abandoned places, landscapes, woodlands, pathways, statues and even flying houses.

The Literacy Shed also hosts video clips for inspiring writing and is choc-full of ways to use them. The Night Zookeeper Shed is well worth a visit. There are short videos, activities and resources to inspire creative writing.

Once Upon a Picture

Once Upon a Picture is another site packed with creative writing picture prompts, but its focus is more on illustrations than photography, so its offering is great for letting little imaginations soar.

Each one comes with questions for kids to consider, or activities to carry out.

How to improve creating writing

Developing story writing

If you decided to climb a mountain, in order to be successful you’d need to be well-equipped and you’d need to have practised with smaller climbs first.

The same is true of creative writing: to be successful you need to be well-equipped with the skills of writing and have had plenty of opportunities to practise.

As a teachers you need to plan with this in mind – develop a writing journey which allows children to learn the art of story writing by studying stories of a similar style, focusing on how effects are created and scaffolding children’s writing activities so they achieve success.

- Choose a focus

When planning, consider what skill you want to embed for children and have that as your focus throughout the sequence of learning. For example, if you teach Y4 you might decide to focus on integrating speech into stories. When your class looks at a similar story, draw their attention to how the author uses speech and discuss how it advances the action and shows you more about the characters. During the sequence, your class can practise the technical side of writing speech (new line/new speaker, end punctuation, etc). When they come to write their own story, your success criteria will be focused on using speech effectively. By doing this, the skill of using speech is embedded. If you chose to focus on ALL the elements of story writing that a Y4 child should be using (fronted adverbials, conjunctions, expanded noun phrases, etc), this might lead to cognitive overload. - Plan in chances to be creative

Often teachers plan three writing opportunities: one where children retell the story, one with a slight difference (eg a different main character) and a final one where children invent their own story. However, in my experience, the third piece of writing often never happens because children have lost interest or time has run out. If we equip children with the skills, we must allow them time to use them. - Utilise paired writing

Children love to collaborate and by working in pairs it actually helps develop independence. Give it a go! - Find opportunities for real audiences

Nothing is more motivating than knowing you will get to share your story with another class, a parent or the local nursing home. - Use high-quality stimuli

If your focus is speech, find a great novel for kids that uses speech effectively. There are so many excellent children’s stories available that there’s no need to write your own. - Use magpie books

This is somewhere where children can note down any great words or phrases they find from their reading. It will get them reading as a writer.

Below is a rough outline of a planning format that leads to successful writing opportunities.

This sequence of learning takes around three weeks but may be longer or shorter, depending on the writing type.

Before planning out the learning, decide on up to three key focuses for the sequence. Think about the potential learning opportunities that the stimuli supports (eg don’t focus on direct speech if you’re writing non-chronological reports).

| Week 1 – Immersion into the stimuli | Week 2 – Practising skills | Week 3 – Creating writing |

|---|---|---|

| Engage with the stimuli through drama, reading comprehension, character work and short writing exercises. | Practise the writing focuses for the sequence. | Share writing genres and discuss the specific elements contained within, always referring back to your writing focuses. |

| Draw attention to the sequence focuses and how they are employed in the stimuli. | Do further short writing activities. These might be writing in a genre previously taught. | Write with modelling. Put scaffolds in place if needed. Hold one-to-one conferences if possible. |

Ways to overcome fear of creative writing

Many children are inhibited in their writing for a variety of reasons. These include the all-too-familiar ‘fear of the blank page’ (“I can’t think of anything to write about!” is a common lament), trying to get all the technical aspects right as they compose their work (a sense of being ‘overwhelmed’), and the fact that much of children’s success in school is underpinned by an ethos of competitiveness and comparison, which can lead to a fear of failure and a lack of desire to try.

Any steps we can take to diminish these anxieties means that children will feel increasingly motivated to write, and so enjoy their writing more. This in turn will lead to the development of skills in all areas of writing, with the broader benefits this brings more generally in children’s education.

Here are some easily applied and simple ideas from author and school workshop provider Steve Bowkett for boosting self-confidence in writing.

- Keep it creative

Make creative writing a regular activity. High priority is given to spelling, punctuation and grammar, but these need a context to be properly understood. Teaching the technicalities of language without giving children meaningful opportunities to apply them is like telling people the names of a car engine’s parts without helping them learn to drive. - Model the behaviour

In other words, when you want your class to write a story or poem, have a go yourself and be upfront about the difficulties you encounter in trying to translate your thoughts into words. - Go easy on the grammar

Encourage children to write without them necessarily trying to remember and apply a raft of grammatical rules. An old saying has it that we should ‘learn the rules well and then forget them’. Learning how to use punctuation, for instance, is necessary and valuable, but when children try and apply the rules consciously and laboriously as they go along, the creative flow can be stifled. Consideration of rules should, however, be an important element of the editing process. - Keep assessment focused

Where you do require children to focus on rules during composition, pick just one or two they can bear in mind as they write. Explain that you will mark for these without necessarily correcting other areas of GaPS. Not only will this save you time, but also children will be spared the demotivating sight of their writing covered in corrections (which many are unlikely to read). - Value effort

If a child tries hard but produces work that is technically poor, celebrate his achievement in making an effort and apply the old ‘three stars and a wish’ technique to the work by finding three points you can praise followed by noting one area where improvements can be made. - Leave room for improvement

Make clear that it’s fine for children to change their minds, and that there is no expectation for them to ‘get it all right’ first time. Show the class before and after drafts from the work of well-known poets and extracts from stories. Where these have been hand written, they are often untidy and peppered with crossings out and other annotations as the writers tried to clarify their thoughts. If you have the facilities, invite children to word process their stories using the ‘track changes’ facility. Encourage children to show their workings out, as you would do in maths. - Don’t strive for perfection

Slay the ‘practice makes perfect’ dragon. It’s a glib phrase and also an inaccurate one. Telling children that practice makes better is a sound piece of advice. But how could we ever say that a story or poem is perfect? Even highly experienced authors strive to improve. - Come back later

Leave some time – a couple of days will do – between children writing a piece and editing or redrafting it. This is often known as the ‘cooling off’ period. Many children will find that they come back to their work with fresh eyes that enable them to pick out more errors, and with new ideas for improving the piece structurally. - Try diamond 9

Use the diamond ranking tool to help children assess their own work. Give each child some scraps of paper or card and have them write on each an aspect of their writing, such as creating strong characters, controlling pace and tension, describing places and things, using ‘punchy’ verbs etc. Supply these elements as necessary, but allow children some leeway to think of examples of their own. Now ask each child to physically arrange these scraps according to how effectively they were used in the latest piece of work. So two writing elements that a child thinks are equally strong will be placed side by side, while an aspect of the work a child is pleased with will be placed above one that he / she is not so happy with. - Keep it varied

Vary the writing tasks. By this I mean it’s not necessary to ask children always to write a complete story. Get them to create just an opening scene for example, or a vivid character description, or an exciting story climax. If more-reluctant writers think they haven’t got to write much they might be more motivated to have a go. Varying the tasks also helps to keep the process of writing fresh, while the results can form resource banks (of characters, scenes, etc) for future use. - Help each other

Highlight the idea that everyone in the class, including yourself, forms a community of writers. Here, difficulties can be aired, advice can be shared and successes can be celebrated as we all strive to ‘dare to do it and do our best’.

Browse more ideas for National Writing Day.