Teaching creativity – is it possible?

It’s one of the 21st century’s most touted ‘soft skills’, and a key driver in schools. But can you actually impart originality and imagination on children?

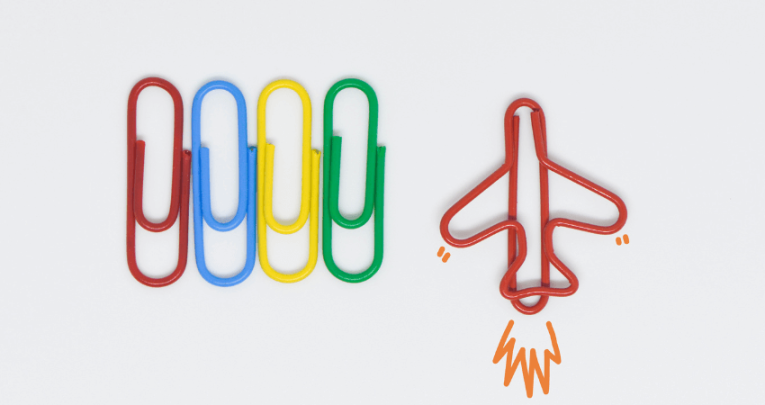

Test yourself. Take a pen and something to write on. Choose one of the following objects:

- a paperclip

- a piece of paper

- a chair

Now try to think of as many possible ways to use the object as you can.

This is known as the ‘alternative uses’ task or test. It was originally devised by Guilford in 1967 for the purpose of assessing people’s creativity.

The test became more widely known after it was used by Sir Ken Robinson in his popular TED talk, Do schools kill creativity?

Perhaps your paper was not big enough to note down all your ideas. If so, great! You might be a creative genius in the making… but maybe not.

The test measures the quantity of your ideas but not their quality. So don’t give up the day job just yet.

One thing, however, is certain, because research has proved it: intelligence and creativity are not the same thing (Sawyer, 2011).

It does indeed seem at first glance as though this test measures creativity as an easily transferable, general skill.

However, David Didau and Nick Rose argue that all attempts to measure creativity suffer from the same lack of validity and reliability.

Types of creativity

So, let’s ask another question. Of the following two options, who do you think will come up with the most (qualitatively) creative solutions for fixing a leaking sink?

- a musician

- a plumber

The answer seems obvious: the plumber. But who would be most creative when it comes to writing a song? Probably the musician.

Just because the plumber is creative at finding solutions for leaking sinks, this does not mean that they are automatically creative in other fields.

Creativity takes many different forms in many different domains, and experience and expertise in a domain can always strengthen a person’s creative abilities.

In other words, creativity is not a general, overarching skill. In fact, creativity is not really a skill at all but is more a human quality or ‘trait’, which cannot be learned to any significant degree, in contrast to the more influenceable ‘states’, which are personality characteristics that remain relatively stable over time.

But although creativity is very difficult to learn, it doesn’t mean what a person already possesses cannot be stimulated by organising the best possible environment.

Smith and Firth (2018) have offered the following definition of creativity: ‘The ability to create something, ideally something that is useful or entertaining in some way. Typically, this is going to involve a rearrangement of existing parts or concepts (words, musical notes, mathematical notation, etc.) rather than making something completely new and unrecognizable.’

In other words, creativity is about making new and useable combinations of existing information.

Viewed in this way, we can’t consider creativity in isolation from domain-specific knowledge and skills.

We have already seen this with the musician: great at writing songs, sometimes rubbish at fixing sinks.

Education plays a huge and important role in developing the necessary knowledge and skills that allow creativity to express itself.

Can you learn creativity?

Short answer: no, but we can stimulate it and bring it to the surface by creating the right conditions.

Long answer: the good news is that most research has confirmed that we become more creative as we get older.

This is only logical, since by then we have acquired much more domain-specific knowledge, which is what you need to be qualitatively creative.

Does this mean that basic knowledge is less important and that we no longer need it? Far from it!

This is a major misconception: we still need schools to teach this crucial domain knowledge to our children and young people. It is the first important step on the way to improving their creativity in the long run.

In summary (and based on a broad vision of creativity): without knowledge there can be no creativity (probably).

How to stimulate creativity

- Encourage pupils to make connections between different domains of knowledge. For example, when teaching about the planets (science), let your children also calculate the distance and size of them (maths). Or combine maths with the concept of a timeline in history.

- Create a psychologically safe learning climate.

– Children must feel confident to experiment and think ‘out of the box’ without the possibility of being criticised or laughed at by their teachers and classmates.

They must have the courage to take risks, make mistakes and be themselves.

One way to do this is to ensure that creative tasks are not marked with points or grades. Stress to ‘perform’ can limit a creative spirit.

– As a teacher, also ensure that pupils are not harshly criticised or ridiculed by their classmates. They must be free to exchange ideas, however seemingly bizarre, without fear.

Establish an atmosphere in which out-of-the-box thinking is valued and appreciated. - Invest in ‘away time’.

– Our minds need a certain amount of away time, time when we do not need to concentrate or be attentive.

– Make sure that your pupils have sufficient time to be ‘unaware’ or ‘absent’.

This kind of ‘time-out’ is not only useful for allowing our brains to relax, for processing emotions and for putting things in perspective but also helps to bring our creative inspiration to the surface.

– Creative ideas often emerge when you least expect it: under the shower, during a walk, tidying up your room, just doing nothing… Free time is not wasted time.

– With this in mind, allow your pupils sufficient play breaks, quiet moments, chat time, etc.

It is an illusion to think that children and young people can concentrate non-stop throughout a 50-minute lesson. - Encourage daydreaming or mind-wandering.

– During periods of away time, encourage pupils to clear their heads and let their minds wander. This kind of random and fragmentary thinking stimulates creativity. - Encourage sufficient sleep.

– This is not always easy with children and young people but it is a crucial factor.

After your REM sleep (the dream phase), you reach a kind of hyper-associative state in which your thoughts are given free rein, some of which resurface in your waking hours.

Like daydreaming, night-time dreaming is also good for your creativity (Smith & Firth, 2018). - Develop routines and habits.

– Developing an automatic approach to certain tasks (like your morning routine or cooking a meal that you have cooked a hundred times before) means that you no longer have to think about them consciously, so that you once again free up capacity in your brain for the kind of thinking that can lead to creativity (De Bruyckere, 2018).

The Psychology of Great Teaching, by De Bruyckere, Hulshof & Missinne is out now (£22.99, Sage)