National Poetry Day – Best 2025 poems, resources, assemblies and ideas

Celebrate National Poetry Day 2024 with these great lessons, activities and ideas for KS1-KS4…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Explore creative ways to celebrate National Poetry Day with your students and turn your classroom into a vibrant space of literary expression…

When is National Poetry Day?

National Poetry Day falls on the first Thursday of October. That means this year, National Poetry Day is on Thursday 2rd October 2025.

What is National Poetry Day?

National Poetry Day is an annual mass celebration that encourages everyone to make, experience and share poetry with family and friends.

What is this year’s theme?

The theme for 2025 is yet to be announced, but the theme for 2024 was ‘counting’.

Ideas for celebrating National Poetry Day 2025

Zero-prep video prompt lesson

Watch our video featuring CLiPPA-nominated poets posing different intriguing questions. Then use our free accompanying narrative poem lesson plan to help KS2 pupils write their own original narrative poems.

National Poetry Day Assembly

Celebrate National Poetry Day with the help of verse by Joseph Coelho, Michael Rosen, Rachel Rooney, Karl Nova and Victoria Adukwei-Bulley…

This assembly plan is based around the theme of ‘truth’. It features KS2 poems and will last around 30 to 40 minutes. All children will require a small piece of paper and a pencil.

The assembly references and introduces five poems that have been selected by National Poetry Day. These are all very different, but each introduces an idea of what truth can mean in the context of poetry.

Download an editable teacher script, a PDF of all of the poems, and watch the poets reading out their work.

Pie Corbett lessons for National Poetry Day

Each of the resources in this exclusive Pie Corbett KS2 Poetry Collection feature original poems based around a theme, and accompanying activities.

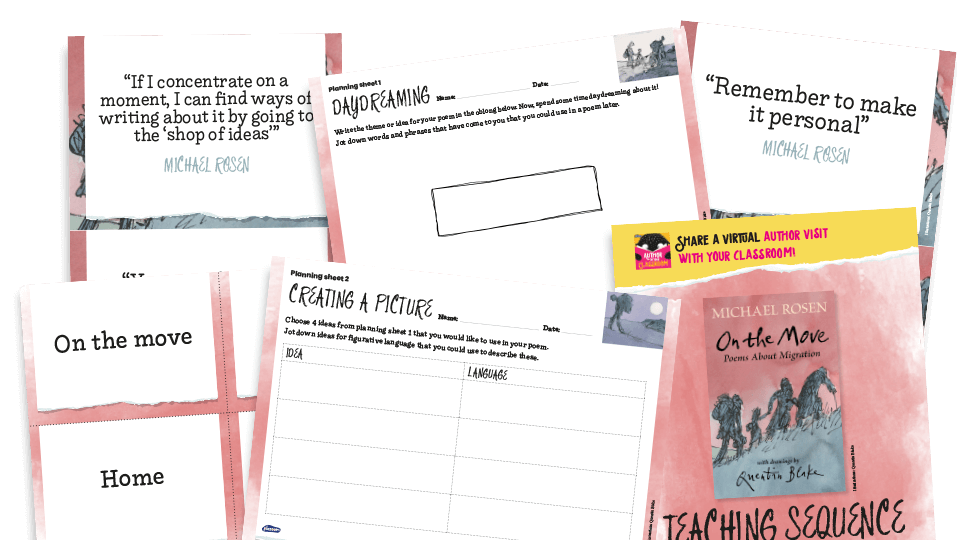

Michael Rosen podcast for National Poetry Day

The Author In Your Classroom podcast has been created especially for sharing in schools. In each episode, a beloved children’s author shares writing tips and advice, and there’s an exclusive resources pack to go with each episode too.

Episode 16 features Michael Rosen talking about migration and his poetry collection ‘On the Move’. Download the free resource pack to receive a PowerPoint, poem, images for a KS2 poems wall display, planning sheets, teacher notes and more.

Download resource packs focusing on comprehension, vocabulary and composition

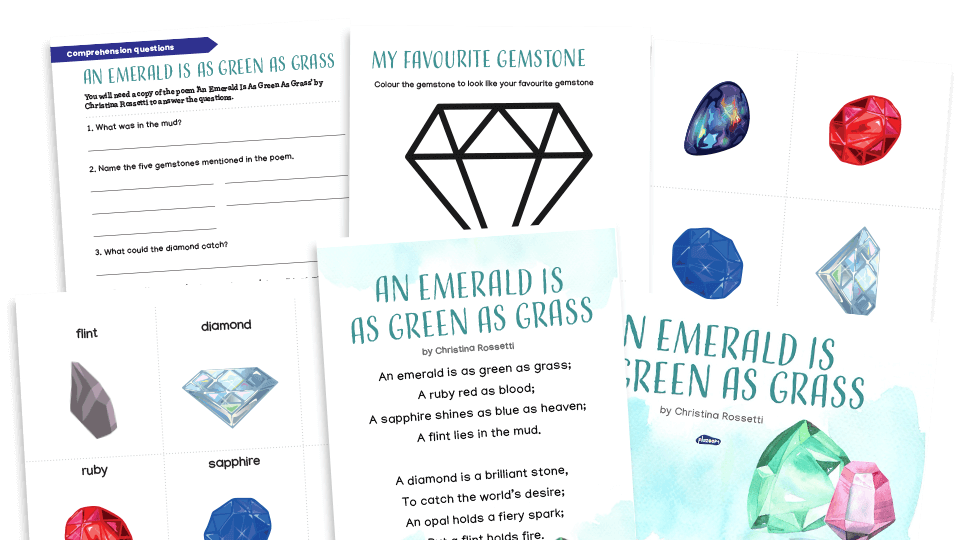

Use these poetry resource packs from Plazoom to cover a classic poem over five sessions.

In KS1, pupils will explore ‘An Emerald Is As Green As Grass’ by Christina Rossetti, including the author’s use of similies.

LKS2 pupils will look at ‘The Eagle’ by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and explore how the author uses figurative language.

For USK2 pupils, it’s classic poem ‘Jabberwocky’ by Lewis Carol, with a focus on exploring what the nonsense words could mean and also their word class.

Explore the CLiPPA shortlist

About the CLPE Poetry Award (CLiPPA) with 2018 winner Karl Nova from CLPE on Vimeo.

The Centre for Literacy in Primary Poetry Award (CLiPPA), is the only award presented solely for published children’s poetry. It’s a great place to start if you’re looking for some brilliant contemporary poets to study.

Visit the CLiPPA website to browse previous winners and find out about the free CLiPPA Shadowing Scheme.

You can read 2024 CLiPPA winner Matt Goodfellow’s thoughts on embracing diverse accents through poetry here.

Refugee poem lesson plan

In this KS2 lesson plan, a refugee poem provides a moving depiction of the effects of forced migration. Students will prepare a reading of the poem, paying attention to the speaker’s evolving mood, and explore how the poem transforms personal hardship into a symbol of recovery.

Dr Seuss KS1/2 activity pack for National Poetry Day

This free Dr Seuss activities pack includes three separate poetry activity sheets, each based off a different Dr Seuss book.

- One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish (Reception/Year 1) – Explore rhyming words and make a fun hanging fish display

- Green Eggs and Ham (Year 2) – Explore rhyming words and write your own foodie poems

- Oh, The Places You’ll Go (Year 3) – Write a short poem introducing someone to your home, school or town

With each one you can read through the extract with your class, use the activity prompts provided, then get children to tackle the main activity.

Then there’s an additional creative task if you want to carry on your Dr Seuss-themed lesson.

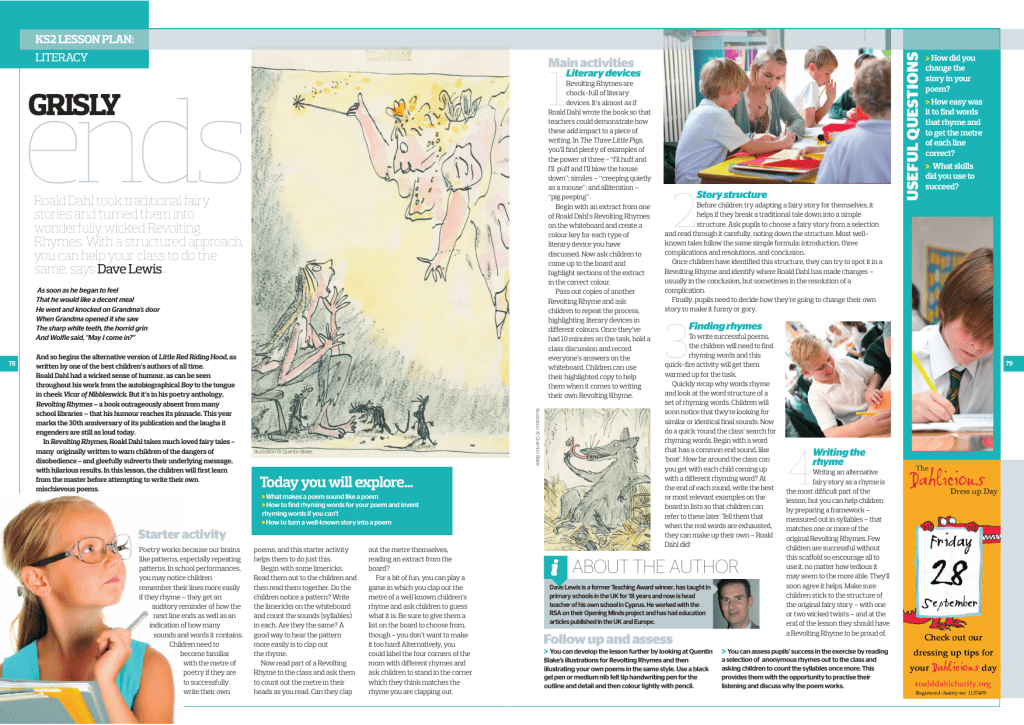

Write mischievous poems like Dahl’s Revolting Rhymes

Roald Dahl took traditional fairy stories and turned them into wonderfully wicked Revolting Rhymes. With a structured approach, this KS2 lesson plan can help your class do the same.

Trending

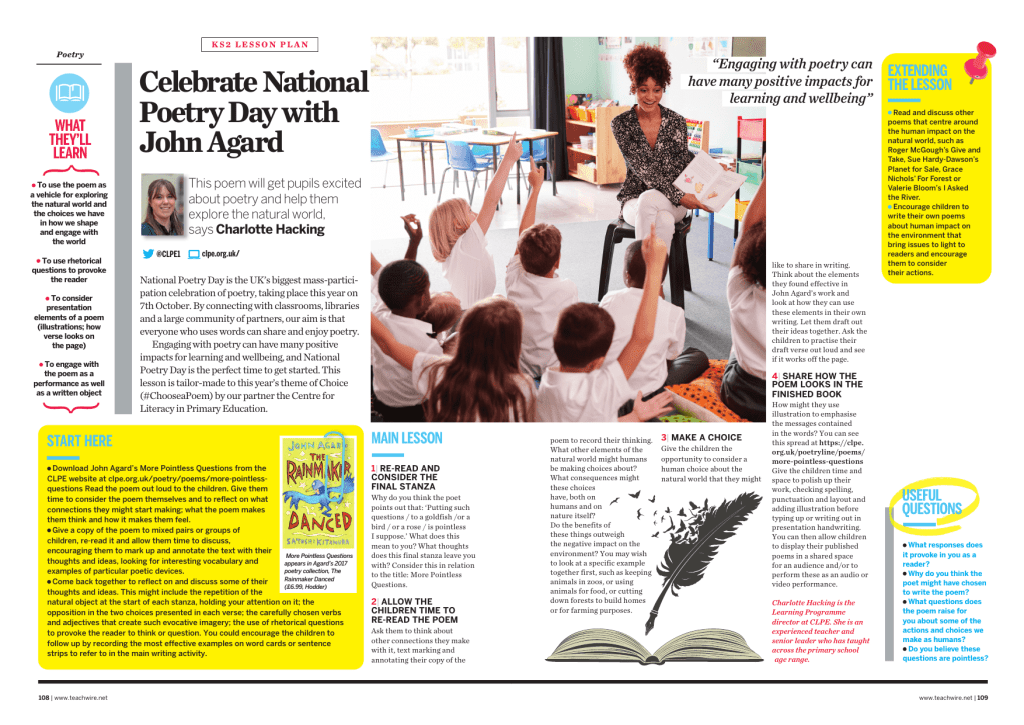

Explore the natural world with John Agard

This KS2 lesson plan focuses on John Agard’s poem More Pointless Questions. Pupils will use the poem as a vehicle for exploring the natural world.

They’ll also learn about using rhetorical questions to provoke, and how to consider the presentation elements of a poem.

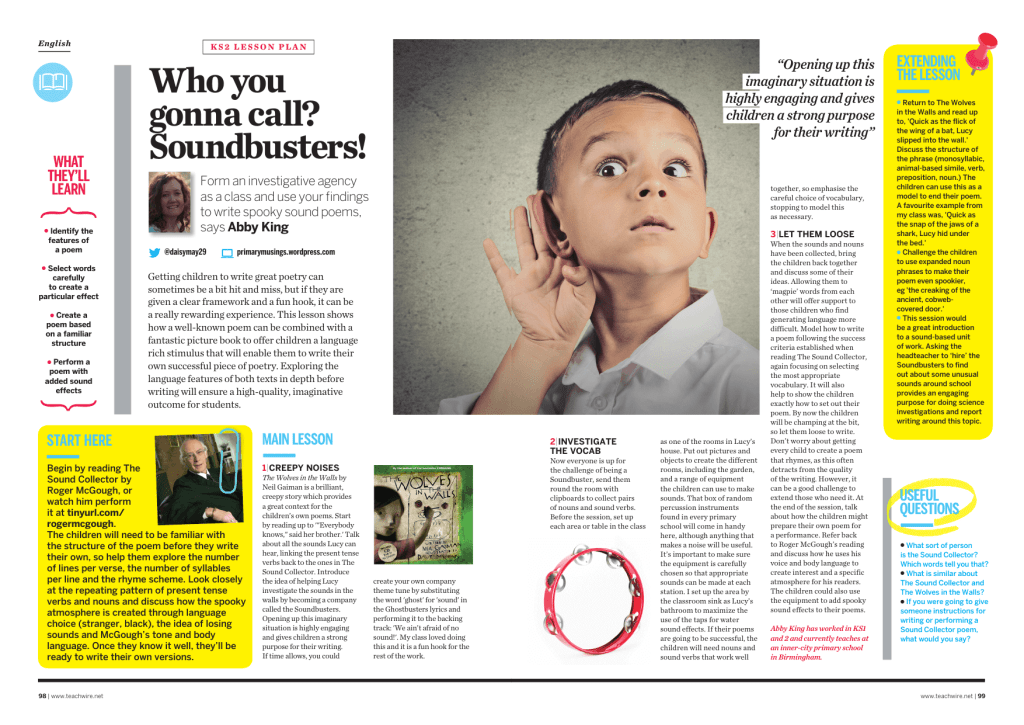

Write spooky sound poems inspired by Neil Gaiman

Getting children to write great poetry can sometimes be a bit hit-and-miss, but if they are given a clear framework and a fun hook, it can be a really rewarding experience.

This KS2 lesson plan shows how a well-known poem can be combined with a fantastic picture book to offer children a language rich stimulus that will enable them to write their own successful piece of poetry.

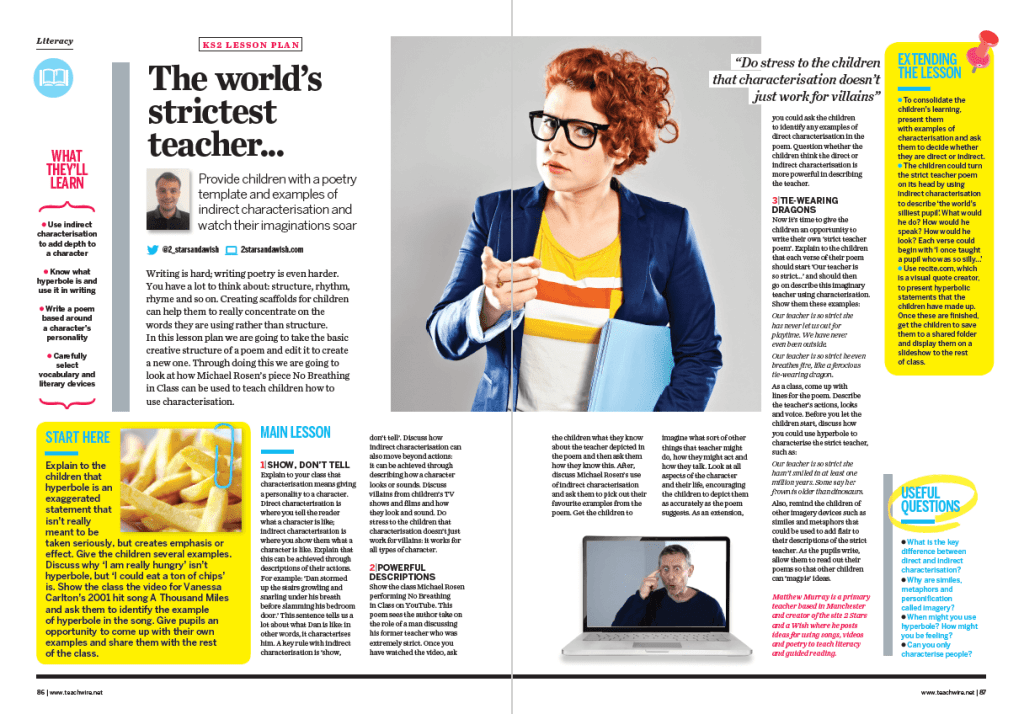

Creating imaginative characterisation in poetry lesson

Writing is hard; writing poetry is even harder. You have a lot to think about: structure, rhythm, rhyme and so on. Creating scaffolds for children can help them to really concentrate on the words they are using rather than structure.

In this KS2 lesson plan your students are going to take the basic creative structure of a poem and edit it to create a new one.

Through doing this they are going to look at how Michael Rosen’s piece ‘No Breathing in Class’ can be used to teach children how to use characterisation.

The Tear Thief book topic

Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy imbued this tale of a ghostly character who moves invisibly through the night collecting children’s tears with poetic language and powerful message about emotional truth.

This three-page PDF with KS1 cross-curricular activity ideas helps you explore the characters, and look at the metaphors and similes in the text, as well as the way the book uses the language of sound to create atmosphere.

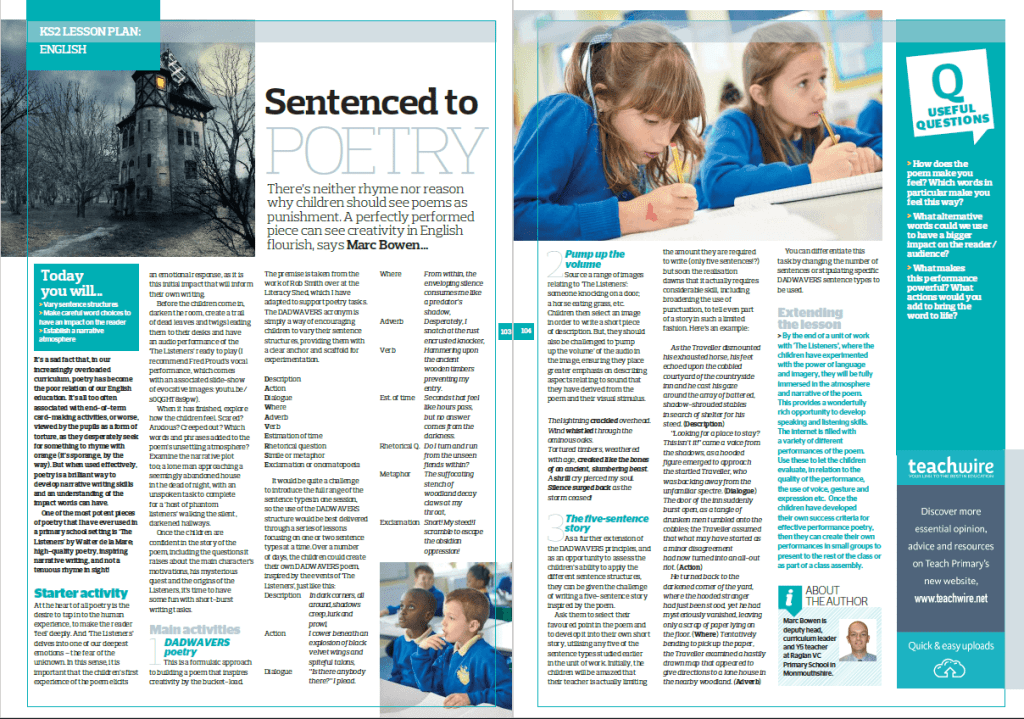

Use a perfectly performed poem to see creativity flourish

There’s neither rhyme nor reason why children should see poems as punishment. Used effectively, it’s a brilliant way to develop narrative writing skills and an understanding of the impact words can have.

This KS2 lesson plan uses one of the most potent pieces of poetry you can use in a primary school setting – ‘The Listeners’ by Walter de la Mare.

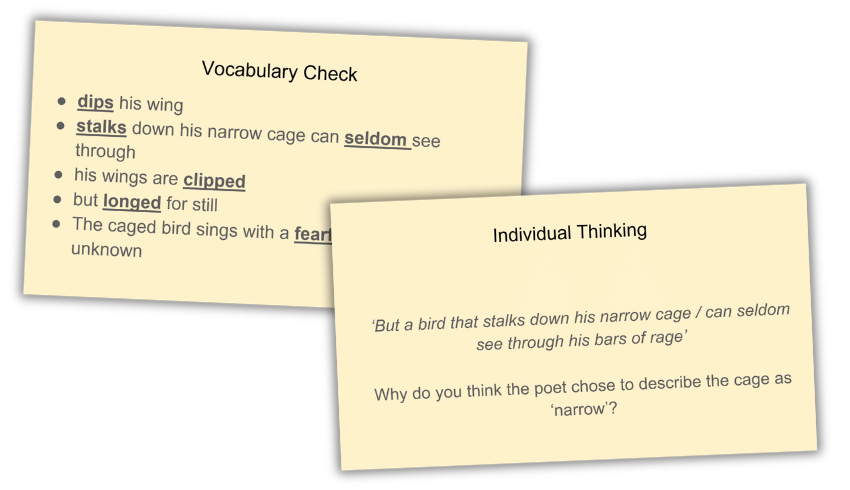

Study Caged Bird by Maya Angelou

This comprehensive KS2 resource explores the poem Caged Bird by Maya Angelou, which explores themes of freedom, oppression and the longing for liberation.

Designed to facilitate a deep understanding of the poem, this resource breaks the poem into manageable chunks for detailed study.

National Poetry Day resources for KS3-4

In the past poetry has received a bad rep with students, and really who can blame them? No teenager wants to have ‘Daffodils’ rammed down their throat for weeks on end.

National Poetry Day is the ideal opportunity to explore the wonders of poetry in a way that won’t scare young students off it for life.

And of course you needn’t stick to the classics – try modern poets; explore different eras, nations and styles; check out the writers of the Harlem Renaissance. Stretch yourself as much as you would your students.

Top tips for teaching perfect poetry lessons

Get your KS3/4 students writing, analysing and comparing poems like masters of verse, with this expert advice CPD set.

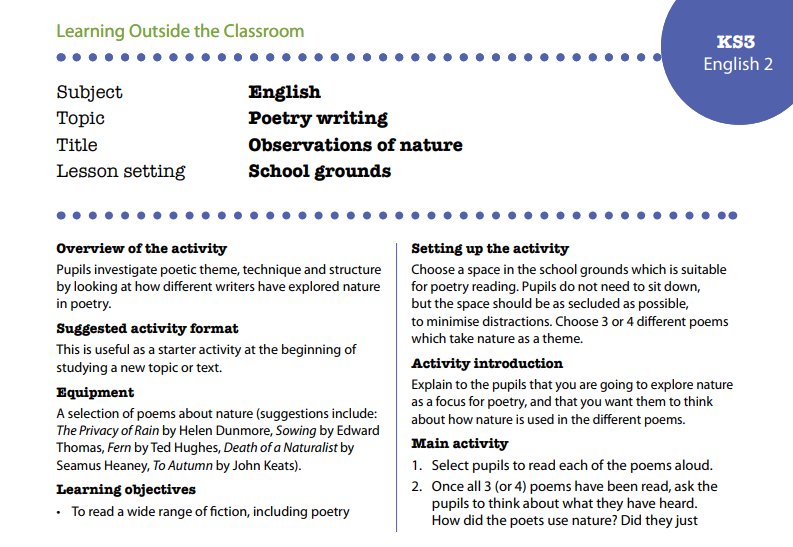

Observations of nature

What’s poetry without a wistful wander through woodlands? This KS3 lesson plan from Learning Outside the Classroom will encourage your students to recognise a range of poetic conventions and understand how these have been used, to perform poems in order to generate language and discuss language use and meaning.

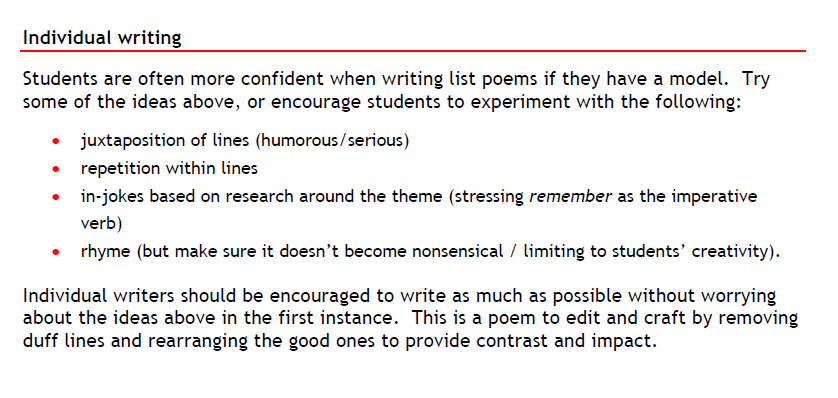

Remember, remember

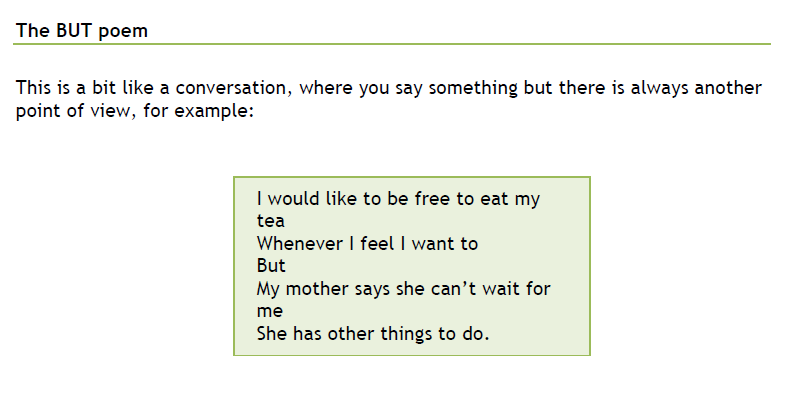

This KS3/KS4 lesson plan uses a semi-completed list poem as a writing prompt for your class to complete.

It starts with simple, literal ideas like ‘Remember to brush your teeth’, but then lets you play with language and imagery with sentences like ‘Remember to turn out the darkness’.

Writing about freedom

Written especially for National Poetry Day, this resource includes two creative prompts for students to come up with their own poems on the theme of ‘freedom’.

It explores the ways ‘freedom’ can be portrayed in poetic language, and guides students to write about it in whatever way they see fit.