Friendship activities – Games and advice for EYFS, KS1 and KS2

Some children need more help with friendships than others. These friendship activities and pearls of wisdom will help pupils connect with their peers and navigate social situations more effectively…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

These friendship activities will develop children’s social skills, help you create a positive school environment and prevent bullying.

Friendship activities and resources

Positive friendships KS2 resource pack

This free one-hour-long, fully resourced positive friendships PSHE lesson explains the qualities that people often look for in a good friend. You’ll discuss toxic friendships, the qualities needed for building positive relationships and more.

KS1 ‘What makes a good friend?’ activity

Use these KS1 friendship activities from literacy resources website Plazoom to discuss what makes a positive friendship. There’s a card sorting activity, then follow this with a short writing activity.

Communication lesson plan

Support your pupils in building stronger friendships with this free communication lesson plan from Emily Azouelos, designed to improve their ability to give clear instructions, listen attentively, and collaborate with kindness and clarity.

All About My Friend worksheet

This free All About My Friends worksheet is a fun and thoughtful resource to help children reflect on the people they love.

It’s ideal for encouraging pupils to think about their friendships, what they enjoy doing together, and what makes their relationships special.

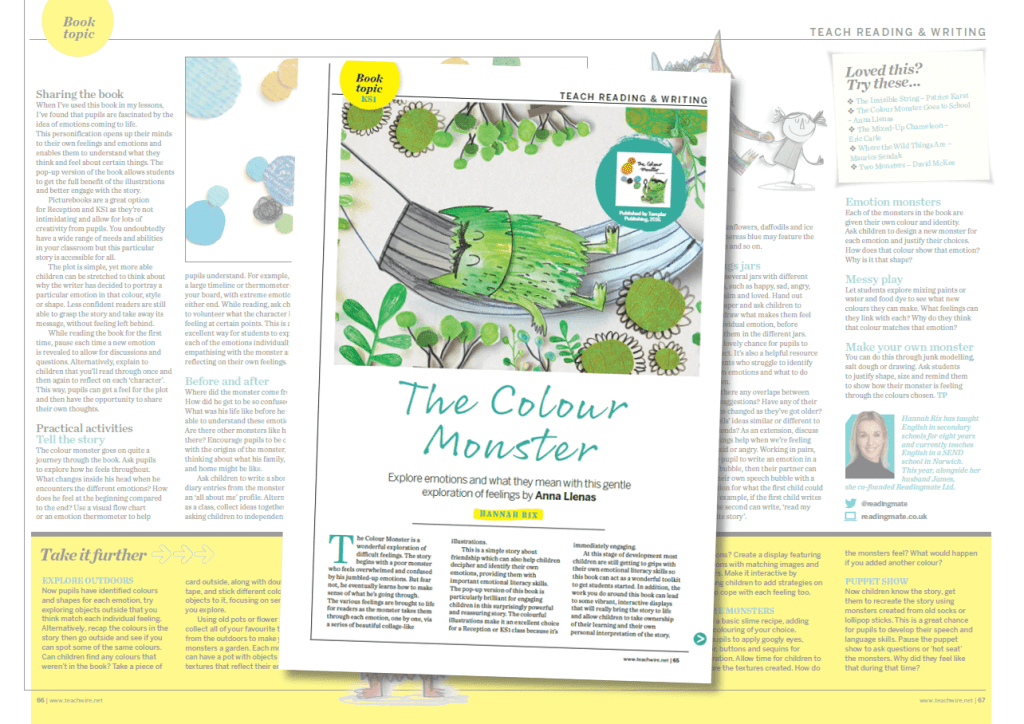

KS1 book topic

The Colour Monster by Anna Llenas is a simple story about friendship and emotions. Use this free page of activity ideas to explore the book with your KS1 pupils.

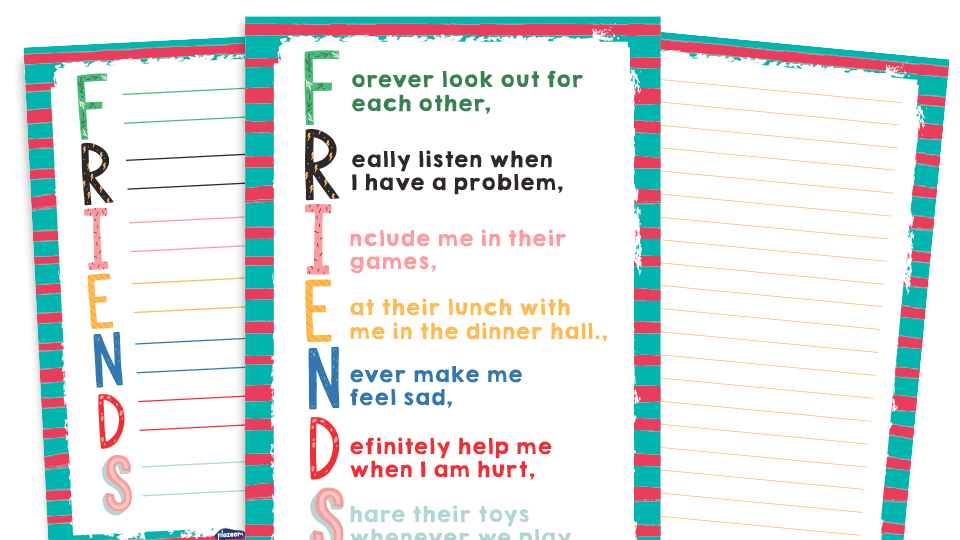

KS1 ‘friends’ acrostic poems

This free KS1 poetry resource pack from Plazoom will give your students the chance to write an acrostic poem all about friends. The teaching notes will also help you lead a class discussion on friendships and what makes a good friend.

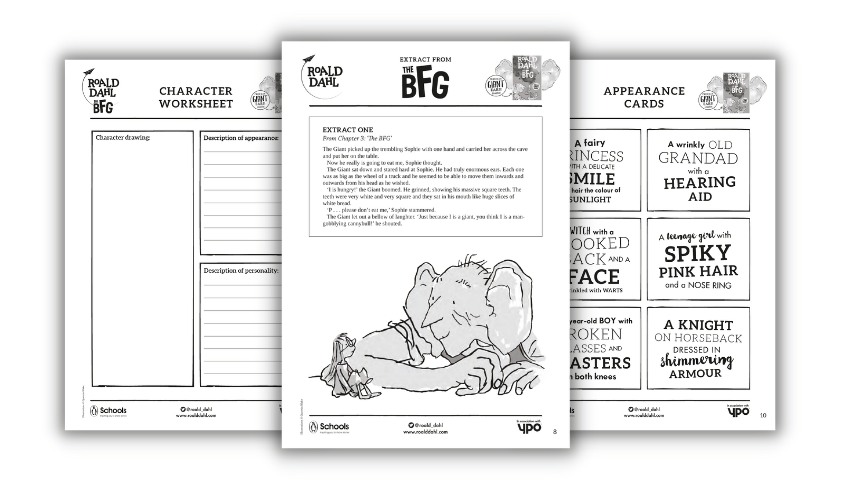

BFG lesson plan

Does how someone looks always match what kind of person they are? Explore this topic with your class with these free Roald Dahl activity cards and lesson plans for KS1 or KS2. Then learn how to write interesting characters in your own stories.

Best books about friendship

We know that children don’t fully develop skills like empathy until later in life. This is why there are so many stories on friendship and how to treat people aimed at young children.

Here are our picks for some top tales that touch on various aspects of friendship that kids will love. They’re perfect for building friendship activities around.

Little Puppy Lost

Holly Webb (Little Tiger Press, paperback, £6.99)

This is Holly Webb’s debut picture book for a younger audience. It tells the tale of a puppy who manages to become separated from his young human when he’s taken to the park for the first time. He’s then befriended by a lonely but streetwise cat, discovers his inner courage, and eventually finds his way home.

Bugs in the Garden

Beatrice Alemagna (Phaidon Press, hardback, £6.95)

This charming little book is about a group of bugs who decide to leave the security of their blanket home to explore the big, wide garden. They want to look for new friends. However, in the event they’re too scared to approach any of the creatures they come across. This is a great circle-time read.

Penguin and Pinecone

Salina Yoon (Bloomsbury, paperback, £5.99)

Penguin is an earnest little fellow who always wants to do the right thing. So when he realises that his new friend, Pinecone, can’t thrive in the cold, he reluctantly packs up his sledge and takes him back to the warm forest where he belongs.

Harris the Hero

Lynne Rickards (Picture Kelpies, paperback, £5.99)

When Harris the puffin flies off in search of adventure, he’s not expecting to take part in the rescue of a baby seal who has drifted too far from his rocky island home. Nor is he expecting to meet a companion with whom he can set up a nest of his own. This book’s gentle message is about how helping others can often have unexpected benefits.

Marmaduke the Very Different Dragon

Rachel Valentine (Bloomsbury, paperback, £6.99)

Marmaduke isn’t how dragons are “supposed” to be. He’s shy, with enormous ears, sticky-out scales, and wings that he never even opens, because of how dramatically different they are. He feels rejected. But that’s only until he meets Meg, a princess who is also nothing like what’s expected of her royal position.

Specs for Rex

Yasmeen Ismail (Bloomsbury, paperback, £6.99)

It can be difficult for children when they suddenly become aware of a small but very obvious difference between them and their peers. For example, they might wear glasses while none of their friends do.

This story follows Rex’s first day at school with a pair of specs that are not only new, but also big, round and red.

Olive and the Embarrassing Hat

Tor Freeman (Brubaker, Ford & Friends, paperback, £6.99)

In this funny and touching tale, Olive the cat is given a ‘friendship hat’ by Joe the turtle. It’s so ridiculous that all her other friends laugh at her when she wears it.

Should she take it off and risk upsetting her chum? Or ignore the teasing because the gift was given with love?

Grrrrr!

Rob Biddulph (HarperCollins, paperback, £6.99)

Journey into the woods to meet a bear who is convinced that being first is the most important thing there is. Fred works hard to be a champion in every competition, and he has the medals to prove it. He’s too busy training to have any actual friends, of course; but he has cabinet full of trophies, and that’s surely better, right?

Imaginary Fred

Eoin Colfer and Oliver Jeffers (HarperCollins, hardback, £12.99)

Many youngsters will know exactly what it means to have an imaginary friend. But what must it feel like actually to be one?

That’s the intriguing question explored in this magical book. Fred goes in search of a playmate after having been dropped by yet another chum who has found someone ‘real’ to replace him.

I Don’t Want To Be A Pea!

Ann Bonwill (Oxford University Press, paperback, £5.99)

It’s very easy for good friends to become comfortably locked into complementary roles. But it’s important not to take each other for granted. Hugo and Bella discover this when an invitation to the Hippo-Bird Fairytale Fancy Dress Party forces them to reassess their relationship.

Have You Seen Elephant?

David Barrow (Gecko Press, hardback, £10.99)

A friendly elephant who is very proud of his hide-and-seek skills attempts to conceal himself in a succession of ludicrously inappropriate locations, given his size.

Is the young boy who is supposed to be finding him incredibly unobservant – or touchingly kind in pretending not to notice his hefty chum? Would your little ones ever pretend in order to make a friend feel better?

Lion and Mouse

Catalina Echeverri (Random House Children’s, paperback, £5.99)

Lion and Mouse are best friends. But eventually the big cat’s habit of boasting about how much taller, stronger and louder he is drives his tiny but faithful friend away.

It’s only when he finds himself facing a fear that mere physical bulk isn’t enough to vanquish that the pair are reunited.

Two Little Bears

Suzi Moore (Bloomsbury, paperback, £10.99)

One of them lives in the green mountains, and the other in a frosty snowscape – yet little brown bear and little snow bear have much in common; and when the pair finally meet, a wonderfully natural friendship develops.

Can I Tell You a Secret?

Anna Kang (Hodder Children’s, hardback, £11.99)

Secrets are a thorny issue in any educational setting, and perhaps especially so when the children involved are of an age when they are probably still struggling to understand the idea of boundaries at all, let alone their own, and others’, right to privacy. This book brilliantly unpicks these issues through Monty, a little frog with a big secret: he can’t swim.

I Wish I’d Been Born a Unicorn

Rachel Lyon (Maverick Arts Publishing, paperback, £6.99)

Making friends in new places can be difficult – and it’s all too easy to imagine, when things aren’t going well and we’re feeling lonely or left out, that if only we were bigger, or better looking, or just different, then of course everyone would immediately start to like us. This endearing tale of a hygienically-challenged horse gently explores the fallacy of this assumption.

How to help pupils with SEND make friends

Negotiating friendships can be tougher than many academic challenges for children with SEND, explains educational consultant and author Liz Gerschel. But there are different friendship activities that can make it easier for everyone…

It’s playtime in a primary school: laughter and activity, games and chat. Watching particular children, you see that their attempts to interact with their peers are largely ignored or rejected, not with open hostility, but with indifference.

Many pupils with SEND experience this painful social rejection, lacking the skills to interact with others, communicate effectively and form friendships.

“Watching particular children, you see that their attempts to interact with their peers are largely ignored or rejected”

We are not talking here about deliberate bullying, just the casual exclusion of children who don’t seem to ‘fit in’. It is still hurtful to the recipient and destructive to the social fabric of the school.

For children with speech language and communication difficulties, playtime can be particularly isolating and unhappy. Research evidence suggests that communication difficulties have considerable impact on children’s ability to form friendships, on their self-confidence and on their self-esteem.

Many want to join in with their peers, they just don’t know how to do it. Their social interactions frequently end in frustration and disputes.

The DfE has suggested that the lack of positive friendships is an ‘at risk’ factor for developing mental health difficulties.

Social isolation and friendlessness may also affect learning and attainment, and have a negative impact on adult life. So, what can we do to improve social inclusion?

Friendship activities to try

Introducing a ‘friendship group’

Vicky Absalom, is a SENCO in Tower Hamlets, east London, in a primary school where core values are communication, community, wellbeing, health and a growth mindset.

She introduced a ‘Friendship Group’ to improve social interaction for two Year 3 boys with moderate learning difficulties.

Following an action research model, she observed the children at play, and talked to them and to the midday meals supervisors (MMSs).

The children used ‘Talking Mats’ with clear visual symbols, to express their views. This proved to be a powerful starting point, with pupils sharing strong opinions and showing a willingness to engage.

Both pupils found it difficult to join in a conversation or game. They felt that they were not understood by others. Pupil A declared simply that he ‘had no friends’. Pupil B said that he didn’t like noisy children joining in his games.

“Both pupils found it difficult to join in a conversation or game”

Observations revealed that Pupil A interacted inappropriately with his peers, grabbing at them or shouting at them in close proximity. Pupil B remained largely alone, once briefly joining in a running game but without making eye-contact or conversation.

Neither pupil appeared to understand the social skills needed to build friendships. Pupil B didn’t seem to value friendships or see his peers as potential friends.

The MMSs added that Pupil A made teasing comments, did silly things that others told him to do and then got into trouble. Pupil B was withdrawn and unwilling to speak.

Developing social skills

So what to do? Vicky’s aim was to develop social skills in these two, explore the qualities of friendship with them and enable them to put their new learning into practice in the playground via friendship activities. And she wanted the boys themselves to monitor progress.

Selecting and modifying materials from ‘Talkabout Relationships’, she and the speech and language therapist devised a twice-weekly friendship activities programme led by the SALT and a teaching assistant (TA).

Reasonable adjustments accommodated the children’s difficulties with working memory, attention, auditory processing and self-regulation.

Role play, group writing tasks, turn-taking, sentence starters for spoken language and visual supports involved pupils in practical and enjoyable friendship activities. Each boy had a book with clear visual reminders of the learning, to refer to between sessions.

What makes a good friend?

Both pupils demonstrated in sessions that they knew some of the qualities of a good friend and what they could do to be a good friend. For example, Pupil B said he needed to tell others what he was feeling.

After eight weeks of friendship activities, there were some playground successes. Pupil A thought other children understood him better although his friendships hadn’t improved. He described wariness between himself and his peers. He hadn’t considered letting other children join his game.

“After eight weeks, there were some playground successes”

Pupil B was willing to let other children play with him – even noisy ones. Both children identified continuing difficulties with joining in with someone else’s conversation or game and talking to new people.

Nevertheless, playground observations showed significant improvement in Pupil A’s purposeful play, including a full ten minutes in shared game with peers, facilitated by a nearby adult.

There was no inappropriate social interaction or physical aggression. He was, in fact, interacting successfully with his peer group. Pupil B smiled at a MMS and responded to her question, although he still played alone.

The MMSs suggested that they play group games and used the visuals and verbal cues with which children were familiar, as reminders.

The school has introduced keyrings with visual reminders of what to do to be a good friend as prompts for children and staff. More opportunities to relate the learning directly to the playground, such as through problem-solving in ‘real-life’ situations, are helping to further develop and embed skills and build confidence.

Peer group work

Class teachers, TAs and MMSs have an important role in identifying and modelling social skills and demonstrating respect, care and kindness.

Training and peer support will offer staff opportunities to share good practice and hone their skills. The context for inclusion must be dynamic.

Important as it is to empower those children with SEN to develop skills to join in, equally critical is friendship activities work with the peer group, so that they do not reject such attempts and are willing to initiate inclusion themselves.

Regular reviews

Undertake regular reviews, involving the children, of playground and classroom practice. This might lead to you introducing modifications such as paired and peer work in the classroom, more structured friendship activities or reconsidering the transition to larger playgrounds.

Also make sure to include curriculum initiatives that focus on developing social skills and understanding friendships in PHSE, circle times or buddy systems.

Ultimately, it’s the inclusive and supportive ethos of a school that enables children to take ownership of their relationships, self-refer for difficulties and feel confident that help is available, that will make a significant difference to the inclusion of all children.

- Establish a recognised whole-school ethos, supported by visual and verbal reminders, that values diversity, kindness and friendships. Use assemblies and poster, poetry, drama or rap competitions to publicise this.

- Encourage children to accept responsibilities for their relationships, share their concerns, self-refer for help and to listen to and support each other.

- Ensure the trust that children put in adults in the school to help them is well-founded.

- Train all staff (including MMSs and TAs) to model and support social skills development and communication. Ensure all staff are informed about children with SEN and how to meet their needs.

- Use your curriculum to recognise and value diversity, as appropriate to children’s age and context.

- Create curriculum opportunities to develop social skills and colloboration. Friendship activities can be done via role play, social stories, problem solving, structured group discussions and collaborative work in music, art, games, sport, etc.

- Involve parents. Many worry about their children’s friendships. Offer training for parents so they can support social and communication skills.

- Factors such as transition to a bigger playground can exacerbate the isolation and confusion children experience, so gradually familiarise them with it.

- Regularly observe what’s happening in the playground, tracking particular children. Are they having fun? Regularly review the playground with pupils. What would improve it?

- Introduce a buddy system for the playground with clear aims and job applications. Ask children to explain why they want to do it and provide visible indicators of buddy status eg a cap or sash. Introduce limited terms of office for each buddy and certificates for good practice.

Liz Gerschel is an educational consultant who has trained school leaders and staff for over 30 years, and co-author of The SENCo Handbook (Routledge, £24.99). She currently teaches the NASENCO course, which she helped develop for the IoE UCL. Vicky Absalom is one of her students.

Three important lessons about girls’ friendships

We need a better understanding of why best friendships sometimes run into problems, explains Dr Ruth Woods…

Best friendship has had a bad press in the last few years, criticised by some headteachers as encouraging possessiveness, ostracism, and considerable distress, especially among girls.

Some schools have gone so far as to discourage best friendships, or at least to encourage children to ‘all play together’ instead of demonstrating selectivity.

“Some schools have gone so far as to discourage best friendships”

Yet most of us have seen a more positive side of best friendship, and research backs this up. So rather than throw the baby out with the bathwater, we need a better understanding of why best friendships sometimes run into problems.

I spent over a year at a primary school in London, observing girls’ friendships wax and wane, and learned three lessons from them about what can go wrong.

Lesson 1: social status

Best friendships tend to work better between girls with similar social status.

Peer groups are usually hierarchical, and high-status children are more sought after than their lower-status peers. This was the downfall of Navneet’s best friendship with new girl Zena.

As Zena settled into the school and became more confident, her status rose above Navneet’s. Other high-status girls were increasingly seeking her out.

Navneet responded with threats and ultimatums in a vain effort to secure her best friendship — but her efforts were in vain. Zena was eager to expand her horizons, leaving Navneet resentful and unhappy.

Similar dynamics can develop if both friends have a similar status, but one wants to rise up the hierarchy. If girls have, and accept, similar standing in the peer group, their friendship is likely to be more successful.

Lesson 2: safety net

Problems are less likely for children who have the safety net of additional friendships at school.

Best friends often expect each other to be available to play together every day at school — understandable, since children are just as sensitive to loneliness as adults, describing it in adult-like ways from a young age.

School playgrounds are not nice places to be on your own – highly visible, with little to do that does not require playmates. No surprise, then, that ‘besties’ think that they should always play together – but this can mean that they don’t develop other friendships.

“School playgrounds are not nice places to be on your own”

This is a problem when best friends need a break from one another.

They might have an argument, or one might want to play a game that the other doesn’t enjoy. It’s much easier for a girl to walk away from her best friend if she knows there’s someone else she can play with.

A girl without a safety net faces isolation without her best friend, so may feel the need to maintain the friendship at all costs – even if that means acting possessively or acquiescing to unreasonable behaviour.

Lesson 3: sharing enemies

Girls often expect their friends to share their enemies.

Anjali and Kirendeep were good friends. Occasionally they argued, and when they did, they expected their friends to side with them, polarising the whole peer group into two gangs.

Zena, who was normally friendly with both Kirendeep and Anjali, ‘broke up’ with Anjali and all those in Anjali’s gang, to side with Kirendeep. Later, she ‘made secret friends’ with them at the back of the canteen, out of sight of Kirendeep.

On another occasion, all the girls sided with Kirendeep, leaving Anjali ostracised.

Thanks to their expectations of shared enemies, a simple dispute between two girls could be amplified enormously. This creates situations in which ostracism and deception flourish. While this expectation was not confined to best friendships, it certainly made disputes between best friends more difficult to resolve.

Issues to focus on

My time observing girls’ friendships in the playground taught me that it’s not best friendship itself that’s the problem. Rather, it is best friendship accompanied by social status differences, lack of safety nets, and/or the expectation that friends should share enemies.

These are the issues upon which schools should focus if they want to reduce the problems associated with best friendship. Of these, the most obvious and important one to act on is to develop children’s safety nets.

Schools should provide excellent ‘safety net’ provision in the playground, using a variety of measures such as:

- buddy benches

- organised friendship activities which children can join

- incentives and rewards to encourage children to act spontaneously as buddies

You can also challenge girls’ assumption that friends should share enemies. Finally, you may be able to reduce status differences by teaching children assertiveness and consensus decision making skills.

Dr Ruth Woods is a lecturer in psychology at Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen and the author of Children’s Moral Lives (£31.99, Wiley Blackwell).

How to help children who find friendships difficult

When pupils arrive at school, that day’s lessons are the last thing on their minds.

Instead, their first thoughts are more likely to be: ‘Where are my friends? What will we play at breaktime? Will I have someone to sit with at lunch?’

Having a circle of friends who they can be themselves with is the most important factor in making kids want to go to school, according to research.

However, your experience probably already tells you that some classes have more meanness, exclusion and cliquiness than others, and teaching distracted, unhappy children only makes your job harder.

What the research says

So it may help to be armed with some of the social science research on children’s social relationships. When researchers ask school children which peers they like the most in the class and which they like the least, studies find startlingly consistently results.

The children who get the most likes and fewest dislikes are the 15% classed as ‘popular’. Then there is the ‘accepted’ band, about 45%. They have a group of good friends, but they are not as sought after as the popular children. Few people intensely dislike them either. This is the solid core of the class.

Controversial children

For the rest of the classroom, it’s not so easy. Studies have found that roughly 20% are ‘controversial’ children. Some of their classmates really like these kids, but some intensely dislike them, maybe because they are hyperactive, unpredictable or disruptive.

Then there is the ‘invisible’ 10%, children who social scientists term ‘neglected’. These children are ignored by their peers, possibly because they are socially anxious or lack confidence.

The final piece of the puzzle is the final 10%, described as ‘rejected’ children. These are kids who are disliked by a lot of their classmates, have no friends, and few people want to risk being seen with them.

Children may fall into this group if they have learning or communication issues which mean they don’t pick up on social cues very well, or have missed out on learning social skills at home. They can try to cope by either giving in and trying to disappear or by becoming aggressive.

Read Newcomb, Bukowski, and Pattee’s 1993 research on children’s peer relations for more on this.

Needs of the group

So why do these bands form? And how does it help for teachers to recognise them? The answer is that as part of our survival mechanism, the needs of the group always come first.

As child psychologist Dr Michael Thompson explains in his book Mom, They’re Teasing Me:

“Any class is a drama that requires different characters. The hierarchy and the roles are ‘assigned’ by the universal forces at work in the group.

“Many different roles are needed in group life, and the scripts are given to children based on their temperaments and their willingness to play the role.”

I believe that when we recognise how classrooms fit together, we have a better chance of helping those scraping along the bottom.

After all, when a child struggles with maths, we take steps to make sure that this deficit doesn’t cause them too many long-term problems.

We may take them aside and show them how they can get better. Do the same with social skills by showing children how to decode social cues and look for how their behaviour is viewed by others.

Blurring the lines

You can also help blur the lines between the bands. For instance, it’s probably already obvious who the ‘rejected’ children are in your classroom. They consistently don’t have friends and almost always end up sitting on their own.

But studies have found that when teachers change around seating plans, or give children the chance to do non-competitive, non-academic friendship activities where they can chat, like small crafting circles, the least popular children are more liked by the end of the year.

It gives young people opportunities to get to know each other outside the pigeonholes they have put each other into.

It’s just one of the many things I suggest teachers can do to encourage a more harmonious classroom. By looking out for the different roles that children assume in the classroom, the good news is that we can help to break down the hierarchies that cause children so much stress and upset.

Tanith Carey is the author of The Friendship Maze: How to Help Your Child Navigate their Way to Positive, Happier Friendships (£10.99, Summersdale).