The impact of blended learning on schools’ daily routines

Gordon Cairns finds out how blended learning requires not just the right technology, but a willingness to rethink a school’s culture and daily timetable in order for it to work

A major obstacle facing educational institutions trying to rapidly implement blended learning comes from the expectations prompted by that word – ‘blended’.

If schools were trying to introduce ‘mixed’ or ‘combined’ learning, the joins between home and school would be clearer. Instead, ‘blended’ implies a form of high-quality teaching that smoothly transitions between the classroom and online provision accessed from home.

For school leaders, this means not only having to overcome the numerous technical problems that can limit such access, but creating a working relationship between teachers and students that’s conducted via screens. The challenge has been to attain a uniformity of instruction almost immediately, and, in many cases, from a standing start during a national crisis.

Heavy lifting

It would be fair to say that Chris McShane, chief learning officer at Learning 3D, is ahead of the blended learning curve, having spent nearly two decades as a headteacher implementing classroom and remote instruction across a variety of settings, from struggling state to independent schools.

He therefore speaks from experience when he says, “I feel very sorry for the state education system at the minute, because they’ve been asked to do something they have no experience of.”

As he sees it, the speed with which school leaders have had to implement blended learning – without any meaningful reconfiguration of how their schools are managed – has hardly helped. “When I put this into schools, it was part of a change management system. When I first did it, it took me about five years; I’ve probably got it down to about three now.”

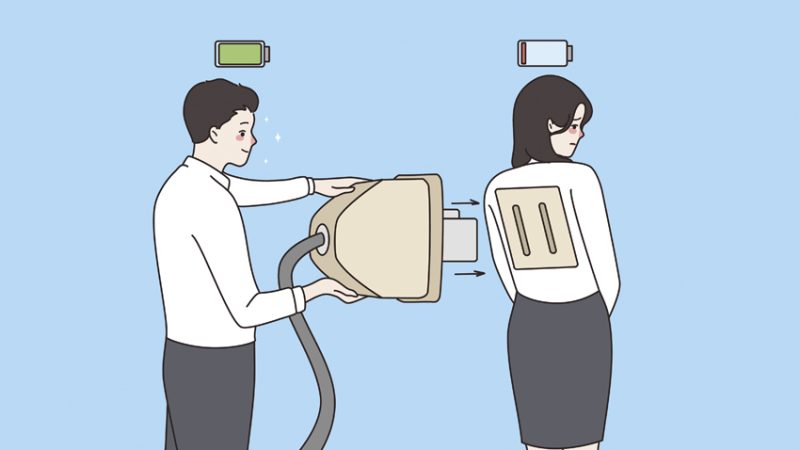

McShane points out that while ensuring learners can access the correct software via a robust internet connection is a big task in itself, that’s not enough. “Technology alone won’t make the difference, but you can’t make the difference without technology,” he says. “We use technology, but it’s not just the technology – it’s the culture and pedagogy that goes with it. The technology just does some of the heavy lifting.”

He goes on to describe a working structure in which teachers remotely plan high quality learning experiences for their students while monitoring, tracking, supporting and challenging them, in a model of pedagogy that resembles coaching and mentoring. It’s McShane’s belief that success in this area may entail reimagining what were once non-negotiables, such as the need for a fixed timetable, the structure of the school day or the pace of learning.

“Do teachers need to stand for five hours in front of their students every day? If you can say ‘No’, that can liberate your thinking around what a school looks like. It’s amazing how flexible the timetable can become.”

Making learning personal

McShane’s advice is that schools should radically rethink how they run the school day in a blended learning situation. “Schools can forget about trying to run a timetable online – you can’t do it. When we went to an online sixth form, the teachers realised you can’t teach how you’ve always taught. So the starting point is, how can we teach?”

One possible approach could be to use an online instructional video that allows students to go offline for half an hour to get on with their tasks, before returning with their completed work. As McShane notes, “You take your hands off because you’ve done your job – it’s all on the video, and then you go back and open the discussion using tools such as Google’s Jamboard or Microsoft’s Sway, allowing the kids to come back with their ideas.

“If you want to encourage more collaboration, you can keep them online and assign them virtual breakout rooms where they can support and help each other. Those who don’t need me can just get on with their work.”

McShane believes that blended learning enables schools to eliminate two of the biggest barriers to learning – stress levels in students and lack of teaching time – thus allowing for a more individualised approach to learning, where classmates don’t measure themselves against each other or struggle to keep up with the pace of learning: “Because of self-pacing, you don’t have the same levels of anxiety in the process. The students are looking at what they themselves are doing, rather than worrying about getting left behind.”

Above all, McShane sees blended learning as not simply a quick fix designed to address a national pandemic, but a positive tool that can change how we educate for the better. “After COVID, schools could return to how it was before but that would be a big mistake,” he says. “We’ve seen that it can actually make learning personal and engage the children much, much more in their education.”

The online penalty

To achieve that goal, however, there’s work that still needs to be done. Data gathered during the first lockdown of English schools in spring and summer 2020 revealed that access to online learning was patchy, with disappointingly large numbers of students disengaged from learning.

The most severely affected were those already among the most disadvantaged, in large part due to the ‘online penalty’ – a concept identified as far back as 2012 by the US academic Ray Kaupp, in a paper examining why Latino students didn’t perform as well as their white counterparts in the California college system.

Justin Reich, an educational researcher and author specialising in networked learning, sums up what he considers to be the biggest obstacle to effective blended learning: “Most people do less well [online], but the people least well served by educational systems typically experience the largest online penalty.

“It seems that the students who don’t have self-regulated learning skills, and don’t live in conditions amendable to self-regulated learning – since in schools, peers and teachers will help them with that self-regulation – can get stuck when they hit these road bumps. Things that would take a person a minute or two to debug can become fatal to a learner’s progress.”

Reich believes that online teaching support of the sort offered by the providers partnering with the government’s recently launched National Tutoring Programme could have a role in helping these disengaged students. “The institutions that seem to be doing the best job of closing this online penalty are those investing in things like coaching and 24-hour hotlines – which generate a real time human connection.”

Reich furthermore contends that these human connections don’t necessarily have to involve class teachers. “If you just don’t care about learning the stuff, you can’t call a 24-hour hotline to make you care; that’s going to require a human being. It might not have to be your physics teacher who makes you care about physics, though – it could be an advisor or coach.”

Somewhat ominously, however, Reich predicts that short-term school closures will become a regular occurrence in future, whether caused by disease or climate change, and that schools will have to build systems in order to cope: “If you’re a kindergartener, this is probably not the last global pandemic you’re going to live through. We’re going to have to accept more interrupted schooling.”

Improve your blended learning practice

- Measure time differently

Planning lessons in minutes rather than time periods can ‘create’ time; a 1,000-minute topic, with 300 assigned to working independently, will expand the available time for the subject. - Be rigorous

The ability of students and teachers to meet any and all deadlines for work set online is key to making progress. - Provide multiple communication channels

Some schools have set up hotlines, text lines or video conference rooms – teachers are only required to respond during set hours, with other individuals being available after hours. - Teachers should make the introductions

When using external materials, it’s important that these are personally introduced by the teacher so that links can be made to the learning area. - Know your definitions

It’s important to be aware of where best to place your resources; online, blended, flipped, distance and remote learning are all slightly different.

Gordon Cairns is an English and forest school teacher who works in a unit for secondary pupils with ASD; he also writes about education, society, cycling and football for a number of publications.