Narrative writing – Examples, lesson ideas and teaching tips

Browse effective strategies for teaching narrative writing and help your students craft imaginative stories while improving their writing skills…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

We explore how to inspire young writers to develop their storytelling skills through engaging narrative writing activities that encourage creativity and build confidence in the classroom…

What is narrative writing?

Narrative writing is where children create stories with a clear structure – beginning, middle, and end – while developing characters, setting and a simple plot.

Practising narrative writing helps students develop their creativity, sequencing and use of descriptive language.

Narrative writing resources

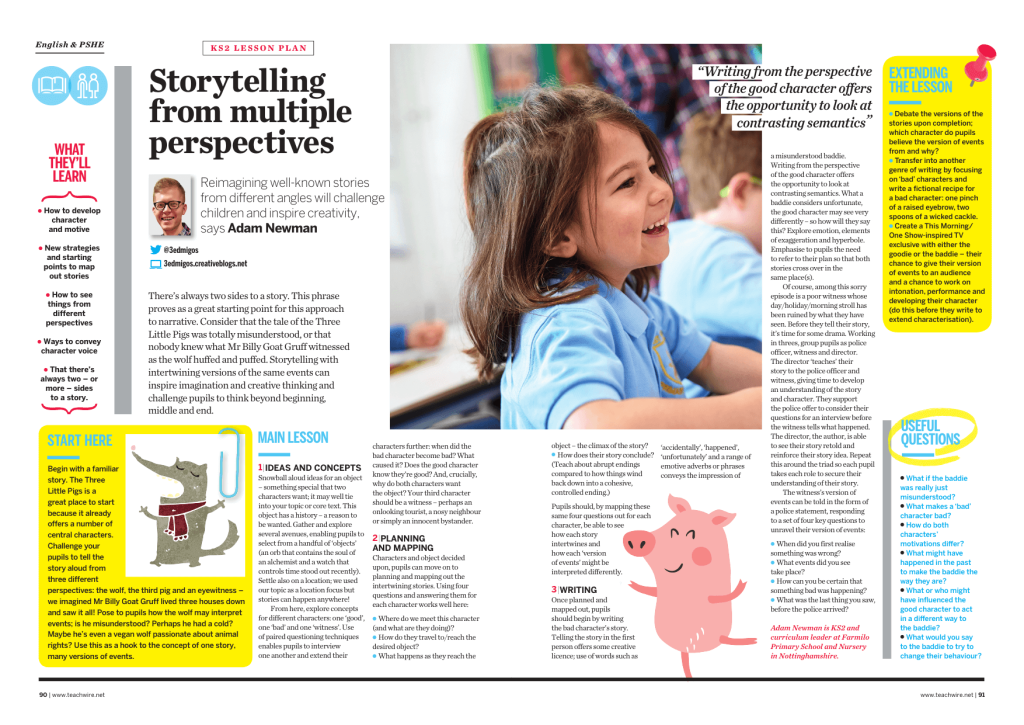

Write stories from multiple perspectives

This free narrative story writing KS2 lesson plan involves reimagining traditional tales from different angles. Pupils will learn ways to convey character voice and that there’s always two – or more – sides to a story.

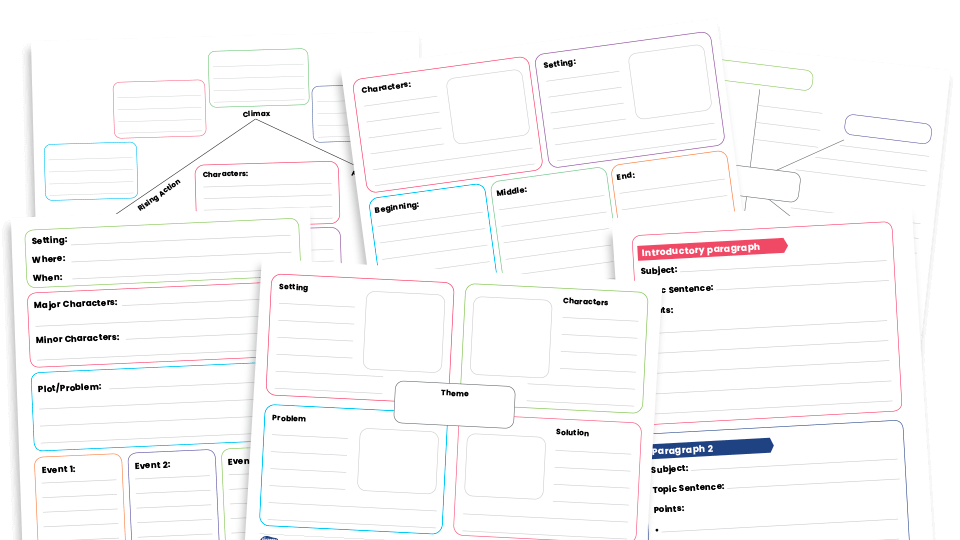

Storyboard templates

A good story needs good structure. These KS1 and KS2 writing template packs from literacy resources website Plazoom contain a range of templates to support children with their story ideas. Alternatively, download our straightforward storyboard template here.

WAGOLL packs from real authors

Peer inside the mind of award-winning authors and help pupils understand how to create engaging characters, captivating atmospheres and suspenseful situations with our collection of free WAGOLL resource packs for primary.

Each teaching pack contains an exclusive extract, a working wall template, teaching notes and worksheets. For narrative writing try these packs:

- Writing from a character’s POV with Liz Flanagan

- Creating a scene of companionable contentment with AF Steadman

- Writing a funny introduction with Joseph Elliott

Story mountain template

Story Mountain is a story structure or story map that can be taught to children to help them with creative writing. Download our free story mountain template.

Teaching vocabulary for narrative writing

Chris Youles explains how to teach pupils to use the best words in their writing and be precise in their vocabulary choices…

If we want to improve our pupils’ knowledge of language and fill them with words with which to charge into battle, then we need to be organised and smart. Most of all, we need to teach them how to be independent in their word choices.

I’ve sat with fellow educators who were wowed by a piece of writing for its ‘gorgeous’ word choices, while I was concerned by its grammatical and sentence construction errors.

I’ve also seen teachers highlight the use of ‘said’ as a weakness, while I’ve wanted to scream that ‘said’ is a perfectly good choice. ‘“I want to suck your blood!” postulated the vampire’ is poor writing.

Discussing language choices

Let’s look at three invented samples from a Year 6 pupil:

- The ancient man looked at the boy and gave him an evil look.

- The decrepit man, wearing a white crimplene shirt and tan trousers, surveyed the boy with a maniacal, withering look.

- The old man gave the boy a withering look.

Which sentence works best? And, yes, this depends on the sentence’s context and purpose, but for now, just choose. What’s your gut reaction?

I would choose 3 as the best. 1 would follow in second, and 2 third. However, time and time again, it seems that the overwritten sentences, like B, garner the most praise.

Discerning choices

Let’s give this sentence a purpose: I want the old man to intimidate the boy and make him feel small. This old man is an incidental character who will not be in the story again. Now let’s examine each sentence again with this purpose in mind.

The ancient man looked at the boy and gave him an evil look.

‘Ancient man’ implies that he is some sort of pre-history Neanderthal. If he’s old, let’s just say he’s old. Also, ‘evil’ doesn’t quite fit the purpose that the more precise choice of ‘withering’ does.

The decrepit man, wearing a white crimplene shirt and tan trousers, surveyed the boy with a maniacal, withering look.

Why ‘decrepit’? This is an adjective meaning infirm or in bad condition. I could instead show this through the man using a walking stick or having a frail body, tired eyes or thin, white, wispy hair.

Is the fact that he is wearing a crimplene shirt and tan trousers important? If so, great! But I’m going to guess that the choice to describe his clothes is an arbitrary one here.

‘Surveyed’ means to look carefully, but this contradicts the ‘withering look’. And ‘maniacal’ means he looks like he’s suffering from mania. (Beatlemania? Wrestlemania?) He is delivering three looks at once: surveying, maniacal and withering. That’s impressive facial mobility for a ‘decrepit’ man.

The old man gave the boy a withering look.

This does the job. ‘The old man’ defines the subject (we could describe him more if he were an important character). I wanted the boy to be intimidated and to feel small, and the ‘withering look’ does this job. It won’t win the Booker Prize, but it’s simple and effective.

We need to model this sort of discussion about language choices in class. This will help create writers who are discerning in their vocabulary choices, and who put purpose at the forefront of their vocabulary decisions.

Using bespoke word lists

One of the most common pieces of feedback I’ve seen in pupils’ English books is to up-level their vocabulary – adding more detail or inserting a ‘wow’ word.

To children, though, this tends to mean grabbing a thesaurus and replacing it with a word that they’ve never heard of, impressing their teacher and their peers with their newfound lexical powers.

So, how should we improve pupils’ vocabulary if we do not use a thesaurus? To start, I would use bespoke word lists.

Create two lists: one for all the key vocabulary they’ll need for the story they’re writing. The other can contain the additional words that will push their writing on, with ambitious choices for the key scenes in the story.

Building a bespoke word list

Recently, my class has been writing their own versions of the ancient Greek myth Perseus and the Gorgons. Before we began, I wrote up the vocabulary that lists the main character names, key locations and any other words related to the story.

For example: Perseus, Gorgon (Medusa), King Acrisius (King of Argos), Danae, King Polydectes.

This gave the pupils every opportunity to get the names right. I’ve seen teachers give lists like this out as spelling homework before. However, I believe we should focus spelling on words that pupils can apply in multiple contexts.

Now that we’ve dealt with the basic story-related words, we must think about the ambitious words we want to teach. For this, I create a bespoke word list, in table format.

Medusa bespoke word list

| Hair | Body | Eyes | |

| Nouns | serpents snakes reptiles tongue(s) | skin claws talons wings | pupils irises |

| Verbs | writhe hiss flick snap slither wriggle | scrape extend | stare pierce scan observe |

| Adjectives | venomous poisonous deadly forked serpentine | leathery scaly grey pale | stony green red purple heartless |

You can create one list for the whole story, or pick out key scenes and create word lists for those. On the left are the word types, and I’ve set out the columns with the subjects.

I have put a single subject in this example, but you could have up to five or six. Subdivide the columns further to focus on specific aspects of a subject.

Nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs

When compiling your vocabulary, list nouns first, verbs second and adjectives third. This doesn’t presume a level of importance to the word types.

However, it encourages pupils to start with precise nouns rather than weak adjectives. For example, ‘Medusa’s long, pointy, scratchy fingers’ can be replaced with ‘Medusa’s talons’.

Next, we have verbs, because we want to create dynamism and action in our scene. Writing in the active voice will always be more powerful for narrative, and using a verb with a noun can do this.

Adjectives can add a shade of meaning that enhances the noun. The adjectives should not be doing the heavy lifting here. ‘Medusa had revolting, mouldy snakes on her head’ is not as effective as ‘Medusa’s head was a nest of writhing snakes’.

Adjectives should be used precisely. ‘Medusa’s stony eyes searched for Perseus’ is far more effective than ‘Medusa had disgusting eyes’.

If appropriate, I also build a short list of adverbs that could be used, but only if they enhance the image. ‘Medusa evilly stared at Perseus’ is better with a more precise verb choice: ‘Medusa observed Perseus with her stony eyes.’

The key here in these discussions you will have with your pupils is that there is never one correct answer. This rich discussion when choosing our words is essential to improving writing.

Chris Youles is the author of the bestselling books Sentence Models for Creative Writing and Teaching Story Writing in Primary. A classroom teacher with 19 years of experience, he has been an assistant head, English lead, writing moderator and a specialist leader in education.

Teaching the basics of narrative structure

The hero’s journey features trials and tribulations, friends and foes. But a child’s journey from novice to accomplished storyteller can be much more straightforward, explains Steve Bowkett…

Life and death, justice, loyalty, freedom, identity, morality, power; all stories are built on such powerful themes.

These are the ideas children explore through story-making, but which are also highly relevant in our day-to-day lives, lying as they do at the heart of much of what concerns us in society.

You can delve deeper into these concepts, as well as perhaps the most fundamental of all – good versus evil – with your class by:

- Identifying themes in books and films with which children are familiar

- Looking at topical news stories

- Making links between the themes. How is justice linked to loyalty? What might be the connections between power and freedom?

Basic narrative elements

Any of these themes, alone or in combination, act as a context for the use of basic narrative elements, the building blocks of stories. These are:

The hero Representing noble qualities such as humility, compassion, patience and selflessness as well as courage. Bearing these in mind allows you to create more rounded and interesting characters.

The villain Representing ‘mean’ qualities such as selfishness, greed, desire for power, ruthlessness.

The problem The villain creates a central problem or crisis that the hero and her companions need to resolve.

The journey Resolving the central crisis takes the hero on a journey, both physically and as a transformative experience.

The partner Both hero and villain can have one or more companions. Important functions of such characters include creating the opportunity for dialogue, acting as a sounding board for the main protagonists and enabling the use of subplots to make the story more layered and interesting.

Help When the main or secondary characters need help, this creates further tension and drama in the story and allows us to realise that they are not invincible. When the hero helps someone, her heroic qualities are brought to the fore. If the villain helps someone, there is often an ulterior motive.

Knowledge and power This commonly expresses itself as the gaining and losing of an advantage. Perhaps the hero loses an important object; a companion might be captured or injured; the villain escapes or learns something vital etc.

An object Stories often feature an important object. Perhaps it needs to be recovered and returned to its rightful owner or its natural keeping place. Sometimes it is dangerous and must be destroyed.

Both themes and these basic narrative elements operate at a deeper level than genre. And you can help children to understand these ideas further by identifying them in different kinds of stories – science fiction, fantasy, historical, etc.

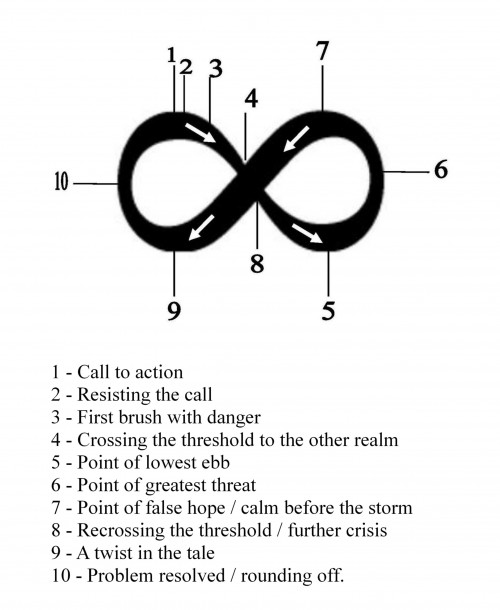

A narrative template

While these simple elements give us a ‘structural underpinning’ for story-making, this basic narrative template shows us the way in which many stories progress.

The left-hand side of the ‘lazy eight’ represents the hero’s familiar day-to-day world, while the right-hand lobe represents new and often dangerous experiences, challenges and encounters that test the hero’s noble qualities.

Ask children to imagine a story as a rollercoaster ride with these key events along the way.

1 and 2 The hero at first is often reluctant to get involved in the crisis, sometimes finding himself caught up in events accidentally. However, for any number of reasons – not least the desire to help others – he soon becomes involved.

3 and 4 Early on in the story, the hero plunges into danger and soon crosses over into unfamiliar territory and new experiences. The hero’s courage and other qualities are severely tested here.

5 The point of lowest ebb. Here, escape or victory seem impossible, but summoning up courage the hero battles on.

6 While things seem to be ‘on the up’, the hero is as far from home as she can be and the danger, while perhaps hidden, is still close by.

7 and 8 Here, victory seems assured and the hero feels on top of things and in control, but we can see that a further plunge into danger is imminent.

9 and 10 Towards the end there is often a ‘twist in the tale’, some final obstacle to overcome before the crisis is resolved and balance and harmony are restored.

Not a formula

It’s important to realise that while we construct many stories around the basic elements and the narrative template explained above, these ideas are not set in stone. We shouldn’t use them inflexibly as a formula for writing.

You can help the children to appreciate this by deliberately ringing the changes:

- What if the hero turned into the villain, or vice versa?

- What if hero and villain teamed up to defeat a greater evil?

- What if the object that the hero is seeking cannot be found?

- What if there were two heroes who were rivals?

Ask children to come up with further examples from books and comics they’ve read and films they’ve seen.

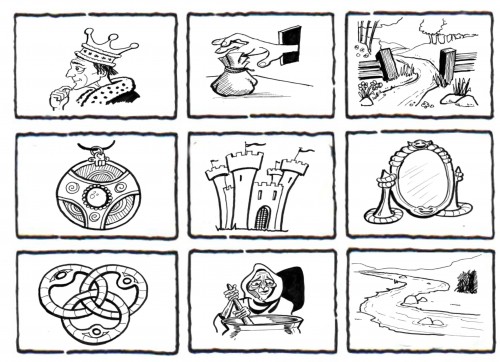

Story grid game

This grid is part of a larger one that consists of 36 pictures and/or words relevant to a chosen genre, in this case, fantasy.

Use two dice rolls to choose the co-ordinates of pictures at random (one roll each of a six-sided die for the x and y axes on the full 6×6 grid).

Focus on each narrative element in turn. Say to the class, “Whichever picture the dice chooses, we will learn something about the hero,” repeating the process for the villain, the journey, the problem and so on.

By the time you reach the bottom of the list, some children will have a complete storyline in mind.

Use the same technique to learn more about the significant points on the narrative template: “We’ll roll the die twice and whichever box is chosen it will tell us something about why the hero didn’t want to get involved,” (point 1).

Or “We’ll roll the die twice and whichever box is chosen will tell us something about how the hero is tested” (point 4).

Choosing images randomly like this takes the mind by surprise and often allows children to have more creative ideas than if they could pick images for themselves.

Narrative writing extension ideas

- Use the story grid as the basis for a board game similar to snakes and ladders. Ask the children to come up with suitable dangers and rewards. Use dice rolls to zigzag up the grid.

- Children do not need to have thought of a storyline at this point: playing the game will often give them enough plot ideas to begin writing.

- Turn the lazy eight template into a straight line, which serves as a visual planner for children to organise their ideas. Get them to write their thoughts on sticky notes placed along the line, emphasising that it’s fine to move these around as the story evolves.

- Cut out the pictures from a story grid and place them face down. Ask the children to turn over two of the pictures and suggest a link that will give them the basic idea for a story.

- Erase some of the pictures from a story grid and ask children to draw or write their own ideas in the blank spaces.

- Invite children to create their own story grids by cutting out pictures from comics or from images grabbed from the internet.

- Make a story grid based on a class reader. Use the techniques above to create new stories based on the characters, places and events the children have read about.