Supporting BAME Headteachers To Stay In The Profession

“Of the 27,000 headteachers across the UK, only 270 are from Black, Asian or Minority Ethnic (BAME) backgrounds.”

- by Viv Grant

In March of this year, Hannah Wilson, co-founder of #WomenEd and champion of #BAMEed gave a TedEd talk entitled ‘Diverse Dreams’ in which she quoted the following facts: of the 27,000 headteachers across the UK, only 270 are from Black, Asian or Minority Ethnic (BAME) backgrounds .

In the mid 1980s, I trained to be a teacher. As part of my degree I chose a module on ‘Education in Multicultural Urban areas’ and heard similarly depressing facts.

As a young black student, I hoped to help buck the trend of urban underachievement and impact positively on the census data for teachers from BAME backgrounds.

In the period since qualifying, I have been a teacher, a headteacher and now an executive coach. After the experience of nearly 30 years in the teaching profession, I have come to the conclusion that if we are to see dreams fulfilled and a rise in the number of teachers from BAME backgrounds taking up headship and staying on, then the solution lies in increasing our understanding of headship itself.

We need to understand the exacting emotional and psychological growth that headship demands and how this interplays with the BAME headteacher’s own inner discourse on race, identity and belonging.

When the sector fully understands both these factors alongside other diversity initiatives, we might begin to see the change that many of us have been looking for.

Understanding the true nature of headship

Many have developed a view of the headteacher role based from the prevailing myth of the Super Head; the armour-clad individual who can stand in the line of fire each day and say, ‘I wasn’t hurt’.

The reality is headship is a deeply personal and, at times, very private endeavour. It is a process of becoming. As schools undergo a process of becoming something greater, something better, those at the helm also undergo a very destabilising emotional and psychological period of growth.

For too long, the profession has neglected this fact. This lack of knowledge and insight has meant that in general headteachers have been ill supported to rise fully to the challenges of their roles. It has also meant that a ‘one size fits all’ approach has dominated the leadership development discourse and has by default neglected the need that heads have for a very personalised approach to their own support and CPD.

To bring about change, we have to begin by increasing our understanding of the emotional and psychological needs of headship. What others have quite rightly termed, the ‘inner work.’

Developing an accurate understanding of the emotional and psychological needs of headteachers

Whether heads are new in post or are long serving, the type of support that they receive is usually concerned with meeting the strategic and operational demands of the role. Their emotional and psychological needs are neglected.

The education system needs to recognise that a head’s appointment to the post is not the destination of their leadership journey.

It should be the beginning or the continuation of a personal development process for which they need not only strategic and operational support, but also psychological and emotional support.

As they attend to the external work of school improvement an accompanying personal inner work also takes place. This inner work often involves:

| • | Deep introspection and self-questioning |

| • | Overcoming periods of self-doubt |

| • | A re-examining of one’s values and beliefs |

| • | Exploration and processing of feelings, emotions and associated behaviours |

| • | A search for meaning and purpose, very often in the most complex and challenging of situations |

| • | A need to establish external stability within their own personal and professional lives |

However, when the inner work is properly supported, heads learn to engage with their role in ways which support both their emotional and psychological wellbeing. They remain connected to their moral compass, their vision and purpose and most importantly, they remain in their roles and fulfil the vision that they hold for themselves and the communities they serve.

And…for BAME heads?

None of this is any different for BAME heads; except in a society where racial inequality still exists, the majority will have at some point, either consciously or unconsciously, had to examine their own racial identity and cultural belonging – an additional psychological demand that comes with its own complex issues for the BAME headteacher.

The history of race relations in this country tells us that for many BAME individuals, their careers within teaching will not have been without its difficulties. In my book, Staying A Head, I describe the destabilising psychological and emotional impact, that others’ prejudice and ignorance had upon me as a young, black, female headteacher.

“Having been brought up in the inner-city and having experienced varying degrees of prejudice throughout my life, I was acutely aware of the racial stereotypes that had shaped my experiences of being a black woman. When I stepped into the headship role, I suddenly found that I had to disprove the negative stereotypes about black women once again. Not only was this very painful, but at times – both psychologically and emotionally – it was a very lonely place to be.

The school advisers, governors and so on were not equipped either to understand or provide the emotional and psychological support that I needed to help me understand how my own background, culture and identity had shaped my experiences of becoming a school leader, as well as other people’s perceptions of me in that role. Both formally and informally, I was told that people were there to support me, however they, or others who passed my way in the form of school support, were ill equipped to help me understand the complex interplay between my own self -image and other people’s perceptions of me.

On more than one occasion, there were visitors to my school, whose responses made it clear that they had not expected to see a young black woman as the headteacher of the school. Outwardly, I always sought to remain composed, calm and in control. On the inside, I felt enraged, upset and full of self-doubt – often all at the same time!”

Stereotype threat

What I have described is what American social psychologist Claude M Steel calls ‘stereotype threat’. He argues that whether we are conscious of it or not many of us experience such a threat in our daily lives and this has a detrimental impact on our psychological and emotional wellbeing.

When I was a head and for BAME heads that I have supported this is a day-to-day reality. Like myself, many do not name it or even recognise it because they have become adept at numbing out their emotional pain from this threat and have normalised their coping strategies.

To the untrained ear or eye, these coping strategies are very often seen as signs of strength and perhaps they are. They enable the individual to show up daily and to carry out the requirements of their role. The question we rarely ask is: ‘At what cost to the BAME individual whose emotional and psychological needs are not fully understood or met?’

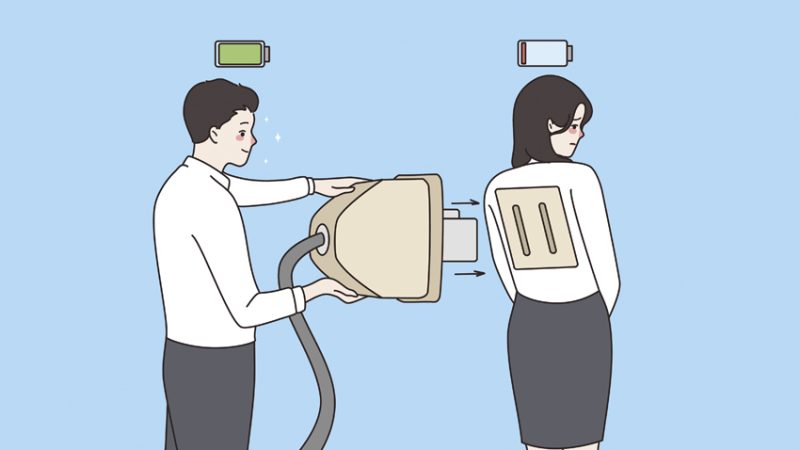

That cost is emotional bankruptcy.

I believe this is a key reason as to why many of our BAME heads fall short of fulfilling their dreams and leave the profession early. They invest huge amounts of mental and emotional energy in trying to ignore differential treatment. They seek to rationalise it, cope with it or deny it and very little is re-invested to help them come back to a place of internal stability.

When large amounts of personal energy are spent seeking to maintain some sort of internal equilibrium, external performance very often suffers.

In the BAME context, poor performance is often judged by negative ethnic stereotype of the individual and when this happens, everyone suffers. The individual suffers because their needs have not been understood and therefore have not been adequately met.

Children in our schools and society suffers because these individuals ‘disappear’ from the teaching profession, their promise, their potential, never fulfilled.

Like Hannah, I too have ‘Diverse Dreams’ that I want to see fulfilled. I too want more of our schools to be led by individuals from BAME backgrounds.

I want to believe that this change is just around the corner. But this won’t happen until the emotional and psychological needs of BAME headteachers are fully understood and addressed.

Viv Grant is the director of Integrity Coaching, an author, occasional education commentator for @Guardian and a passionate advocate for school leaders. She Tweets at @Vivgrant