Spelling games – Best offline and online options for primary

Give these spelling games a go to consolidate spelling skills and eradicate common mistakes…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Spelling is important, but it’s also often frustratingly baffling and outdated – we’re looking at you, ‘Pharaoh’, ‘yacht’ and ‘colonel’! Here are some challenging and fun spelling games primary pupils will enjoy, while boosting their spelling skills at the same time.

Offline spelling games

100+ free worksheets

This extensive pack of ready-made spelling games worksheets for KS2 features a huge number of activities, including for prefixes, suffixes, spelling patterns for sounds, homophones and near-homophones, and ‘spot the spelling mistakes’ games.

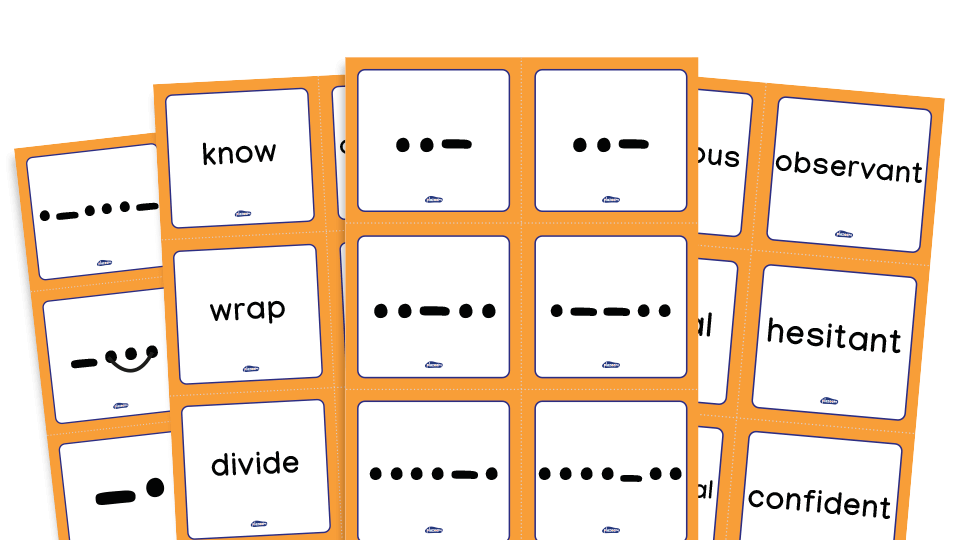

Year 5/6 dots and dashes phonics game

This UKS2 game from literacy resources website Plazoom develops segmenting skills. It helps children identify the phonemes in words and choose the correct graphemes that represent them.

To play you need to find words that match the dots and dashes cards. Dots represent sounds that are spelt using only one letter, dashes represent sounds that are spelt with two or more letters (eg sc in scent, eigh in sleigh, bt in debt).

Browse more Year 5 and 6 spelling list resources.

Memorable strategies and games to make spelling stick

Does your class learn how to spell words one week, only to forget the next? It’s time for a more memorable strategy, says Rachel Clarke…

Children are good at learning lists of words for spelling tests. I know this because I’ve seen plenty of mark books with little rows of 9s and 10s against pupils’ names. What children aren’t so good at doing, however, is learning spellings and then applying them in their writing several weeks after the test.

One way to counter this and ensure pupils retain spelling knowledge long-term is to ensure the teaching of words, rules and patterns is active and engaging – and I’ve got several suggestions on just how to achieve this.

Introducing children to a variety of games and structures that can be used and reused with multiple spelling objectives ensures learning is enjoyable, that children recognise the structures (avoiding the need for lengthy instructions) and that you save time by selecting successful activities.

1 | Kim’s game

This is an adaptation of an old parlour game where a selection of items is placed on a tray. The tray is covered whilst one item is removed. Once uncovered, the players guess the missing item.

As a spelling activity, all you need to do is display the class’ current spelling words on separate cards on the whiteboard. Then ask the children to close their eyes while you remove one of the word cards.

When they open their eyes, the children should try to determine which word is missing and write this on a mini whiteboard. You then need to check their answers for accuracy, replace the missing word card and repeat the game.

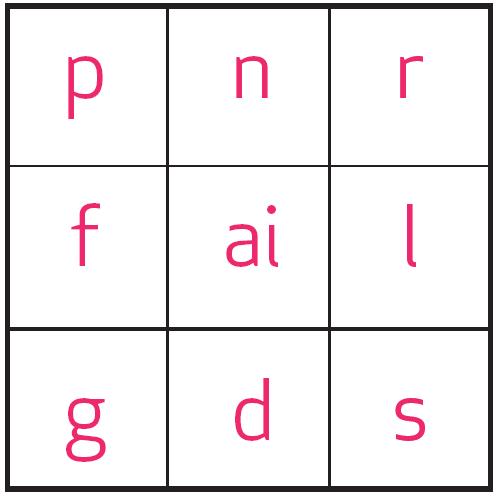

2 | Boggle

Another firm favourite is this popular word game. I find a 3×3 grid is sufficient, but with older children you may want to increase the amount of available letters by making the grid larger.

Ensure that the spelling pattern you have been learning is included in the grid and ask the children to build as many words as they can within the time limit using the available letters. You may need to remind them that they can only use each letter once in each word. This activity works well with competitive children.

3 | Aunt Milly Likes

Every now and again I like to share words with the children without telling them which spelling rule connects them, which means they have to use their powers of deduction to work this out for themselves.

To do this, I use a game called Aunt Milly Likes. All that’s required to play is a simple table on the whiteboard and a succession of clues about what Aunt Milly likes and dislikes.

For example, “Aunt Milly likes waves, but she doesn’t like sand”; “Aunt Milly likes snakes but she doesn’t like snails”; “Aunt Milly likes cake but she doesn’t like biscuits”.

By completing the table with the children, you will be able to listen to their suggestions about the rule and even ask them to suggest further things that Aunt Milly might like. The great thing about this game is that it can be used over and over again with different spelling rules.

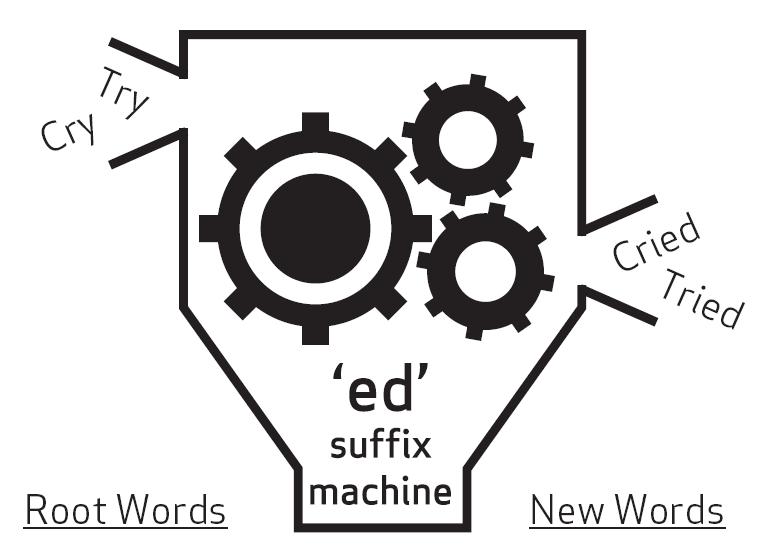

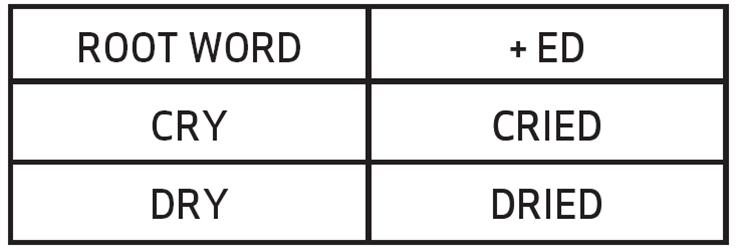

4 | The Suffix Machine

This is a really versatile technique for teaching spelling. All you need is a drawing of a machine on the whiteboard, a label indicating the suffix that the machine adds to words, and a table to record the spelling of the words before and after they entered the Suffix Machine.

You then need to work your way through a list of words, asking the children to predict what will happen to each word once it’s travelled through the Suffix Machine.

As with Aunty Milly Likes, the power of this activity lies in asking the children to explain the spelling rule rather than telling them what takes place. Eg:

6 ways to add sparkle to spelling practice

In addition to fun and engaging teaching, children need to practise learning to spell the words they’ve been taught. We’ve all used the look, cover, write, check method to do this, but what other ways are there to practise new and tricky words? Here are six fun ideas that will keep spelling practice fresh and interesting.

Cross off tricky words

Practise high frequency and tricky words by playing a variation on noughts and crosses. Each player selects one tricky word they need to practise, eg ‘She’ and ‘Are’. They then take turns to write their tricky word in the sections of the noughts and crosses grid, just as they would in the traditional game.

Add colour

Encourage children to add some colour to their spelling practice by writing each word they need to learn in a colour of their choice. Tell them to go over the outline of each word in a different colour. They should repeat this until each word on their list is a rainbowof colours.

Fortune spelling

Create the next playground trend by showing children how to make an origami chatterbox (sometimes called a fortune teller). Encourage them to label each flap with a word from the class spelling list. They should then write encouraging statements such as ‘super speller’ or ‘word wizard’ under the innermost flaps.

Children should then challenge a friend to choose words from the chatterbox, spell them and eventually reveal their spelling fortune.

Skill building

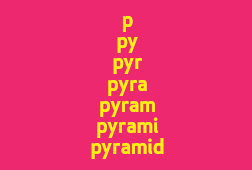

Building a word pyramid is a fun way to practise new and tricky words. Unlike a real pyramid, you start at the top and work down. So, if you were practising writing ‘pyramid’, you’d start with p, then on the next line write py, on the next pyr and so on until you end up with this:

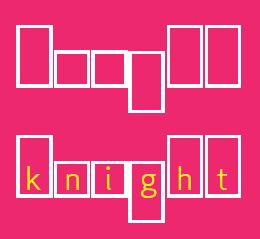

Get into shape

Teach children to recognise the shape of words on their spelling lists by asking them to draw an outline around each letter. Children should then try to fill blank outlines with the words from their spelling list. Eg:

Make a dash

Reinforce children’s understanding of vowels by asking them to write out each word from their spelling list with a dash in the place of each vowel. Having done this, they should then go back and fill in the spaces.

Rachel Clarke (@PrimaryEnglish) is the author of Spelling Rules! Y2 Published by Keen Kite books.

Online spelling games

Busy Things’ Sky Larks

Busy Things’ Sky Larks series contains four games, based on different word lists. Up to four players can compete at any one time, or you can play against the computer. Choose a number of gnats to play for – the more gnats, the harder the word. The aim of the game is to be the first to have 20 gnats.

The different games focus on exception words (KS1), high frequency words (KS1), statutory word lists (KS2) and a complete word bank (all ages). A free trial is available to teachers.

Karate Cats

Struggling with grammar, punctuation or spelling? The Karate Cats are here to help! Chop a capital letter, fly-kick a full stop or smash a sentence in this fun game for KS1 learners. It even features David Tennant as the voice of Sensei.

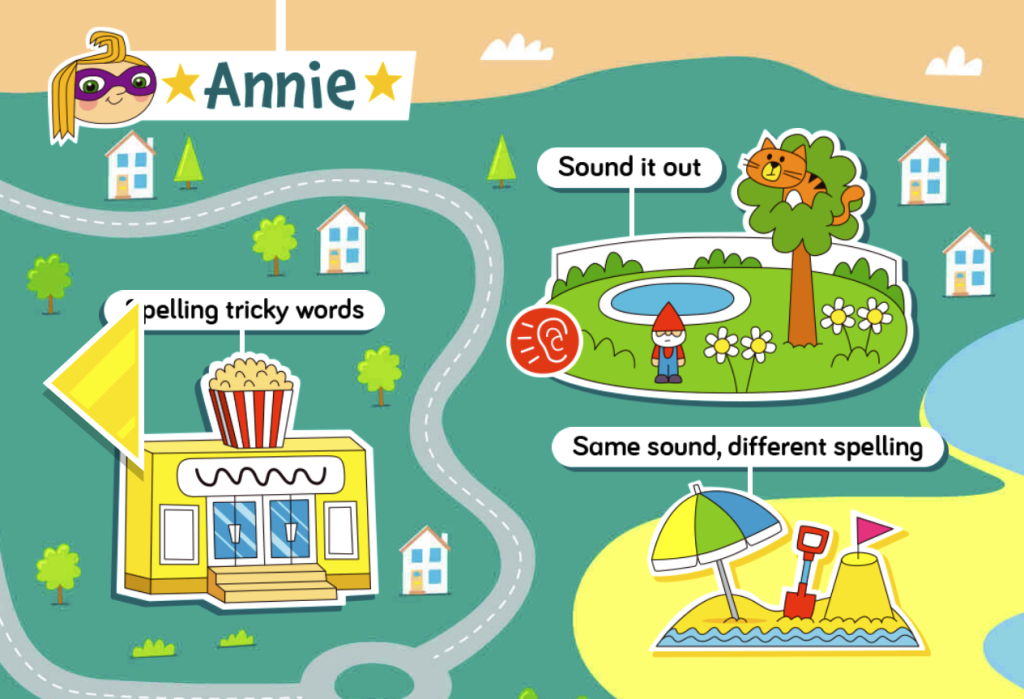

Small Town Superheroes

Perfect for KS1 students, Small Town Superheroes contains 18 mini-games that will test lots of different English skills. Head to the Acrobat Annie section of town to play three interactive spelling games.

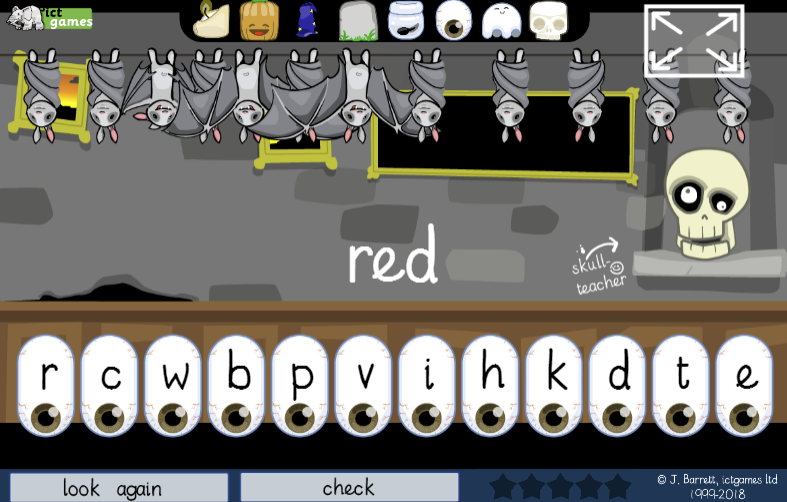

Spooky Spellings

Practise spelling tricky words with this Spooky Spellings game for Y1-6. First, choose your year group, then drag the eyeball letters into the correct order to spell each words. The bats will flap down and take the letters away when you get it right. Spook-tacular fun!

Letter Blocks

This one will keep kids on their toes. It works on the same sort of premise as the word game Boggle, mixed in with a bit of Tetris (or Candy Crush, if that’s more relevant to today’s audience).

You need to find words of three letters or more, where each letter is adjacent (including diagonally) to the next. You can’t use the same letter twice, but click on each in turn, then double click the last letter and those blocks disappear.

More letters keep appearing from the top and the aim is not to let any column get to the top of the screen. Be warned – it’s addictive!

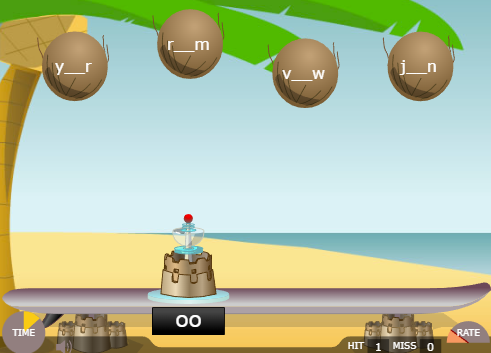

Coconut Vowels

This Coconut Vowels game puts kids’ spelling skills and knowledge of vowels to the test. You will be shown letters that are part of a word, then you have to complete the word by clicking on the coconuts that contain the missing letters.

Browse more SPAG games and Year 3 and 4 spelling list resources. We also have free KS2 spelling worksheets.