School assembly – Motivational ideas for primary and secondary

Make the most of your school assembly and learn what it takes to keep your audience engaged with these ideas and resources…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Unlock the potential of your school assembly with these inspiring and engaging motivational ideas, tailored for both primary and secondary students…

Primary school assembly resources

Teamwork assembly

If you need a way to inject some whizz, pop and bang into your next school assembly, try this Roald Dahl themed option, based around teamwork. You can also easily adapt it to focus on friendship or perseverance instead.

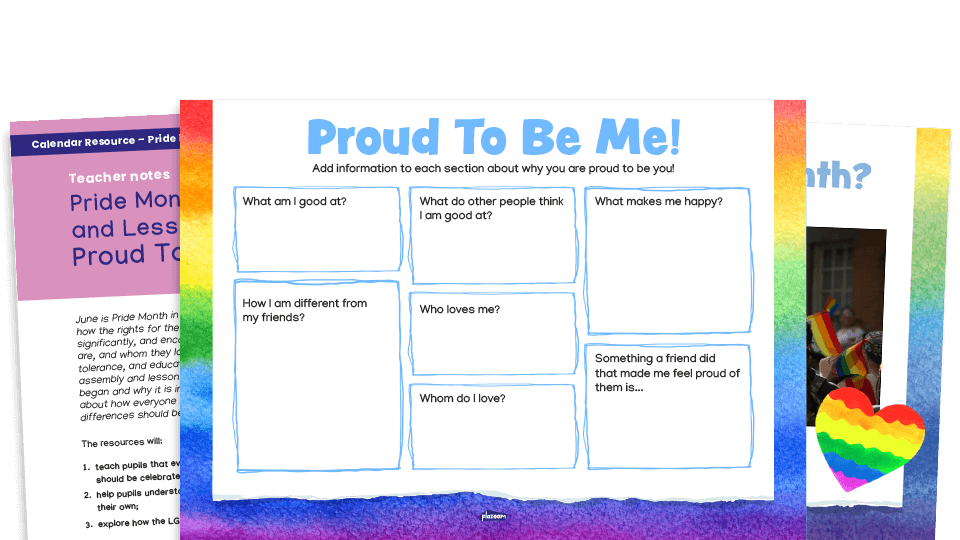

Proud to be me assembly

Are your pupils proud of who they are? This assembly resource from resources website Plazoom celebrates love and the fact that everyone is different. It will give pupils the opportunity to think about what makes them proud of themselves.

Art assembly

Follow the lead of art lead Adele Darlington and host a special art assembly. All children need is a sketchbook and pencil. They’re a fabulous, valuable, shared experience.

Harry Potter assembly

Use this idea by head of school Sarah Watkins to conjure up a little Hogwarts magic into your assembly. Don’t forget to download a full teacher’s script along with all the other resources you need.

Sexism assembly

Introduce the topic of sexism with this free assembly PowerPoint and teacher notes, aimed at UKS2. The assembly covers:

- Masculinity

- Toxic masculinity

- Gender stereotyping

- Is it appropriate for boys to cry?

- Sexism

- How to call out and tackle sexist or toxic behaviours

Poetry assembly

This assembly plan is based around the theme of ‘truth’. It features five poems and will last around 30 to 40 minutes. All children will require a small piece of paper and a pencil.

The assembly references and introduces five poems by Joseph Coelho, Michael Rosen, Rachel Rooney, Karl Nova and Victoria Adukwei-Bulley.

You get an editable teacher’s script, a PDF of all of the poems, and you can watch the poets reading out their work on YouTube.

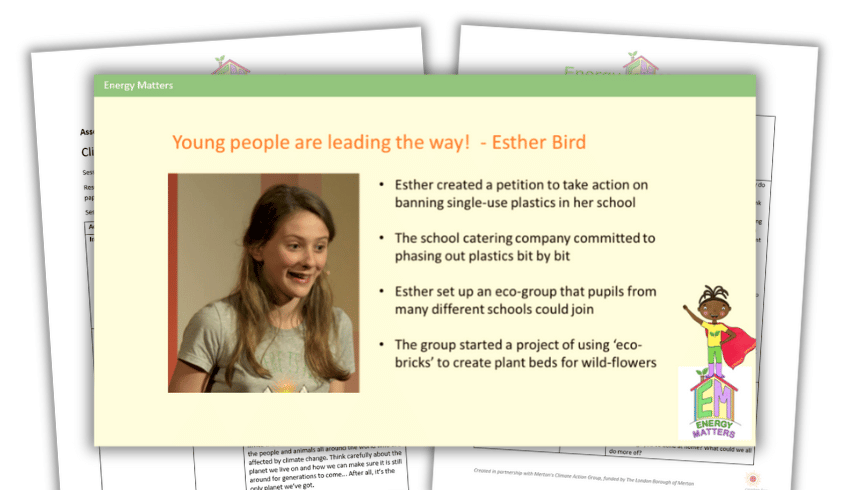

Climate change assemblies

This free climate change assembly from fuel poverty and climate charity, Centre for Sustainable Energy, takes about 30 minutes to deliver. It covers climate change, how it affects humans and animals and how young people can take action.

This assembly plan and accompanying ten-slide PowerPoint presentation from Plazoom is themed around Greta Thunberg, climate change activism and how the children in your school can make a difference.

Secondary school assembly resources

New school year assembly

This assembly for Key Stages 3 and 4 from TrueTube will help your students think about what they want to achieve on the next stage of life’s journey. There’s a short film, some games and a PowerPoint presentation too.

More school assembly resources

Kindness assembly

These two kindness assembly resources – one for primary and one for secondary – can help you spread a little kindness in your primary or secondary school. You’ll get slides, teacher notes and recommendations for videos and stories to use in your assembly.

What makes a great school assembly?

James Handscombe offers his thoughts on how to make the most of your school assembly, and what it takes to keep your audience engaged…

Crafting a powerful assembly takes time. It involves writing 1,500 words in coherent sentences and structured paragraphs so that the listener, without aids to memory or concentration, is at least able to take away the key messages.

This, therefore, is the first characteristic of a powerful assembly – messages that are clearly communicated and rendered memorable.

That said, a great assembly does more than simply hammer home some key messages – it exemplifies the school ethos. It not only tells, but also shows. When sitting in a powerful assembly, you’ll hear described the aspirations of the community, but also see them lived.

“A great assembly does more than simply hammer home some key messages”

Exactly what characteristics the assembly has will thus depend on the ethos of the school in which you work. Using someone else’s assembly as inspiration is wise; downloading and delivering it as written, much less so.

The final characteristic of a great assembly springs from that idea of communicating an ethos. Every assembly is a teaching opportunity. Students should go away having learned something.

Show not tell

To achieve these ends, you can deploy:

- personal anecdotes

- high culture references

- pop culture references

- tales from history

- stories of inspiring heroes

- warnings

To tie it all together, you can draw on your own ruminations and reflections, the words of your foundational documents or the content of assemblies gone by. This is a team effort, of course, since building an ethos is the work of many speakers.

The idea of showing, rather than simply telling is an extraordinarily powerful one for an assembly writer. We encourage students to use their words cleverly and develop a wide vocabulary. Assemblies give them opportunities to see us doing the same ourselves.

“The idea of showing, rather than simply telling is an extraordinarily powerful one for an assembly writer”

Assemblies also remove us from our expertise pigeonholes. A maths teacher can endorse the interests of the history teacher. The English teacher can speak to the beauty of maths.

They allow us to communicate our humanity and tell tales of misspent youth, recount eccentric enthusiasms and share the words and music that make our fragile hearts beat faster.

In an assembly we can pass on the advice and life lessons we long for students to learn, but which simply won’t fit into the timetabled curriculum.

High and low

One of the most challenging decisions you’ll make is how to pitch your cultural allusions. Should you talk about autumn by invoking Axl Rose’s words on the cold ‘November Rain’, or by citing John Keats’ misty and far mellower ode?

My reflection on this is that assemblies are about learning, so we should expose them to things they don’t know. I like to aim just over their heads. Try for content that will be largely new to them, but which they may have at least heard of, dipped into or been intrigued by. This way, they should be looking up and lifted by what is offered.

This approach gives you the opportunity to stealthily drop popular culture references into your discussion with the same gravitas and respect you’d afford great writers from centuries past.

It emphasises that the students’ existing culture is valuable, and worthy of engagement and reflection. It also encourages them to listen out for your roguish tricks. They might just be listening carefully for the next sneaky Taylor Swift lyric, but at least they are listening.

Natural bias

Another challenge is that your cultural touchstones will spring from the minuscule part of human experience that is your life thus far.

On our own, none of us can ever be as culturally diverse as the schools we serve – a natural bias we would do well to monitor and take active steps to remedy.

“On our own, none of us can ever be as culturally diverse as the schools we serve”

Expressing your own character and sharing your culture with students is a real privilege of delivering an assembly, and one we shouldn’t be shy of (Paul Simon and JRR Tolkien are frequent visitors to my scripts).

However, we must also be careful not to give the impression that this is the only culture we’re interested in. Or worse, that this is the only culture that has value.

The poetry of Rabindranath Tagore; the novels of James Baldwin; the history of Sudan – all have an equal claim to time and space. Writing an assembly is an opportunity for us to learn something new ourselves, as well as teach.

Cross-referencing

When approached as a standalone presentation, however, even a truly brilliant assembly will lack power.

An assembly’s greatness comes from its place in a collection, which is why I believe assembly givers should also be listeners. The best cultural reference for an assembly is another assembly – ideally one given by someone else.

These cross-references allow assemblies to reinforce and build on each other. They turn ephemeral, individual pieces into a rich and evolving tapestry of shared understanding.

They can tap into and develop the ethos of the school, and turn a building into a community.

- An assembly is made up of stories, references, a big picture ethos and take-home messages. Start with one and add the others in.

- Your take-home message must be clear; structure the assembly to make it so.

- You are exemplifying good writing for the students; spend time crafting your sentences and paragraphs.

- Remember that an assembly is another opportunity for pupils to learn something, especially advice and life lessons that won’t fit into the timetabled curriculum.

- Your assembly isn’t just what you say, but how you say it. Make sure you’re in touch with the school ethos and its aspirations

- Take inspiration from all walks of life. This includes high culture, pop culture, tales from history, stories of inspiring heroes or warnings from the lives of villains. Ensure these sources are culturally diverse

- Aim high with your content. Assemblies should expose pupils to things that are new to them, or which they may be somewhat familiar with and would like to explore further.

- Have fun with your assemblies. Be your own, idiosyncratic self.

James Handscombe studied mathematics at Oxford and Harvard before training to be a teacher. He became the founding principal of Harris Westminster Sixth Form in 2014. He is the author of A School Built on Ethos: Ideas, Assemblies and Hard-Won Wisdom. Follow him at @JamesHandscombe.

Why school assemblies are easier (and cheaper) than you think

A 20-minute primary school assembly can be a wonderful time for both children and teachers. Young children have a real thirst for knowledge, and an endless fascination with the world around them which we, as teachers, need to nurture.

By providing a great start to the day, children can be inspired and motivated, while teachers can be given ideas and themes which they may want to develop in their own classrooms.

If you’re a headteacher, an assembly is a great chance not only to entertain and enthuse the children, but to prove that even though you are no longer in the classroom, you can still fascinate children and hold their attention with ease. It certainly gives you a great deal of ‘corridor credibility’ with teaching staff.

Start with just one word

Sometimes, I’d start an assembly very simply with just a word. ‘Impossible’, for example. “What does it mean?” I’d say. “Something you can’t do,” the children would reply. And then I’d show that it wasn’t necessarily so.

“By providing a great start to the day, children can be inspired and motivated”

After seating five teachers on a wooden gymnastics bench, I challenged a tiny infant pupil to lift up the bench. The children said it was impossible.

Then, to their great amusement, I put a car jack under one end of the bench and the infant pumped it up with ease. This led to a discussion on other amazing machines and how they work; the crane, for example, which was being used on a housing development opposite the school.

And once I’d shown how the impossible could become possible, more ideas quickly came to mind and provided assemblies for a whole week.

It was easy for a child to cut a hole in a sheet of paper that they could put their hand through, but could they cut a hole in a postcard that they could climb through? Impossible? Not at all.

And surely it was impossible for a sentence like ‘Tom, where Fred had had had had had had had had had had been the correct answer’ to make any sense at all? No, with the correct punctuation it was indeed possible.

Let others take the lead

Children themselves are an amazing resource for assemblies. Many of them will have a hobby or interest, and it only takes a little gentle persuasion for them to be willing to share it with everybody else.

Teachers and classroom assistants can usually be persuaded to do a turn as well. One of my classroom helpers was a dab hand at building Victorian-style dolls’ houses, and the children were fascinated to learn how she constructed all the tiny furniture for them.

“Children themselves are an amazing resource for assemblies”

Simple maths puzzle idea

An interesting assembly can be created from the simplest of ideas and with a minimal amount of preparation. Get a sheet of white A1 paper, a big pair of scissors and a glue stick and you’re ready to go.

Tell the children you’re going to show them an interesting mathematical puzzle. Cut four strips from the paper, each measuring about 60cm x 8cm.

Take the first strip, put a little glue on one end and paste it into a circle. Now say you’re going to push the scissors into the strip and cut all the way round the circle.

As you cut, ask the children what you’ll end up with. They will say, rightly of course, that you’ll end up with two separate loops, each about 4cm wide.

Next, take another strip, join the ends again, but just before you do so, give one end of the strip a half turn. Again cut all the way round the loop, and ask what you’ll end up with. The children will probably say two loops again. In fact, you end up with one very large loop.

Then take the third strip, and before gluing give one end a full turn. What do you end up with this time? Surprisingly, two linked rings. So what would happen if you gave the fourth strip a turn and a half? Or two turns?

Children can experiment with this in their classrooms, but in the meantime you could finish the assembly by telling them about the mathematician Mobius.

Mike Kent was a head teacher for 30 years. He is the co-author of 27 musical plays for primary schools and the writer of three books on education, including Amazing Assemblies for Primary Schools.

Religious assemblies – Why a change in the law would be popular

Robert Cann makes the case for why schools’ collective worship obligations need replacing with inclusive assemblies…

At Humanists UK, we believe assemblies are best when they bring school communities together by focusing on the values that unite everyone – regardless of their religion or belief.

To this end, we’ve been supporting Baroness Burt and Crispin Blunt MP, sponsors of the Education (Assemblies) Bill in the Lords and Commons respectively.

‘Broadly Christian’

Unearthing ancient laws that remain on the statute book long after their time can be an entertaining use of one’s time.

Despite the old wives’ tale, it definitely is illegal to shoot a Welshman with a longbow within Chester’s city walls (or indeed anywhere else), but you definitely must not enter the Houses of Parliament wearing a suit of armour, or you’ll be in breach of the Coming Armed to Parliament Act 1313.

There’s another outdated law, one dating from 1944, that requires every state school in England – including those without ‘religious character’ – to hold a daily act of collective religious worship.

Where schools are faith schools, this worship must be in line with the faith of the school. Where they’re not, it must be ‘broadly Christian’ in style.

This makes the UK the only sovereign state in the world to impose Christian worship in state schools as standard, which is a remarkable legal anomaly given our increasingly secular times.

Daily worship

Some readers might be rolling their eyes at this point. Your own school may have assemblies less frequently than every day, and perhaps without any sign of collective worship at all. Yet many schools continue to comply with this law, either in whole or in part.

“This makes the UK the only sovereign state in the world to impose Christian worship in state schools as standard”

A YouGov poll of parents taken last year found that 20% thought their child definitely took part in a daily act of collective worship, with 25% unsure. Fewer than half (47%) said such daily worship definitely did not take place.

Just because a law isn’t universally complied with, it doesn’t follow that reform is unnecessary. Indeed, the government indicated that if it was made aware of English schools breaching the requirement to carry out daily worship, they would be ‘investigated’ and ‘reminded of their duty on this matter’.

In schools where such daily acts do take place, those children who are withdrawn can, at best, be left twiddling their thumbs, and at worst, be ostracised from their peers as the structured school day starts without them.

No higher authority than the United Nations has got involved, with the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child having urged the UK to repeal its collective worship laws.

Inclusive assemblies

It’s therefore high time that things were brought up to date, which is where the Education (Assemblies) Bill comes into play.

The Bill proposes to remove the collective worship requirement in schools with no religious character. Instead, those schools will have to hold inclusive assemblies that are suitable for all children, regardless of their religion or belief.

These assemblies could, of course, include religious topics, but would lack the worship element.

Collective worship in faith schools would be left alone, though the Bill does specify that children who have been withdrawn from worship in faith schools must be provided with a meaningful educational alternative.

Socially important

A change in the law would be popular. The aforementioned YouGov poll further found that 60% of parents with school-age children oppose enforcement of the collective worship law, while just 24% are in favour.

Parents surveyed in 2019 ranked religious worship last among 13 possible assembly topics, with 29% thinking it appropriate, compared with 76% who opted for ‘the environment and nature’ and 74% choosing ‘equality and non-discrimination’.

“60% of parents with school-age children oppose enforcement of the collective worship law”

The Education (Assemblies) Bill would be both long overdue, and a socially important new law. If you agree with us that inclusive assemblies are the way forward, please contact your own MP and request that they speak up on your behalf in support of the Bill.

Just leave the suit of armour at home if meeting them in person…

Robert Cann is education campaigns manager at Humanists UK; for more information, visit humanists.uk or follow @humanists_uk.