Behaviour management strategies for primary school – Videos & advice

Managing challenging behaviour in KS1 and KS2 children can be tricky, but this collection of expert advice, ideas and opinion pieces can help you keep the mood positive…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

We’ve tailored these expert behaviour management strategies for primary school teachers. Read on for advice on talking to parents, alternatives to behaviour charts and how to deal with low-level disruption…

(We’ve also got behaviour management advice for early years and secondary).

- Behaviour management videos

- Behaviour dos and don’ts

- How to get ahead on classroom management

- Talking to parents about their child’s bad behaviour

- How to use social norms behaviour scripts

- Helping pupils learn from their actions

- Strategies that work better than behaviour charts

- Dealing with low-level disruption

- Get back to September behaviour in six easy steps

- How to help children manage their own volume levels

Behaviour management videos

The reasons for challenging behaviour in the classroom are not always obvious. So what signals are children giving you, and what do they mean? Here, Sue Cowley, teacher and behaviour expert, talks about the types of behaviour she’s seen in the classroom, what has been the real cause, and what’s been the solution.

When you’re facing really difficult behaviour in the classroom, here are eight techniques you can use to restore calm and order. From using the power of names and the art of distraction, to when you really need to send for help…

If the children in your class aren’t behaving, it could be for a number of reasons. Here, we look at seven of the biggest mistakes teachers can make, from lack of consistency in expectations through to letting your emotions rule.

When you see a teacher in complete control of their classroom, what’s their secret? Here, we answer this question and provide more great advice on tricky subjects such as what to do if you feel you’ve completely lost control of your classroom.

View all our behaviour management strategy videos. Find out more about the latest edition of Sue Cowley’s bestselling book, Getting Your Class to Behave. Order it on Amazon.

Behaviour dos and don’ts

Too often, the way in which schools respond to difficult pupil behaviour risks making things worse for everyone. This free Paul Dix behaviour download sets out what you should and should not be doing to manage the behaviour of pupils – particularly those with SEND.

How to get ahead on classroom management

One of the keys to classroom management is forward planning – getting in front of tricky behaviour before it happens, rather than reacting to problems after they occur. Not only does this allow you to avoid the stress caused by poor behaviour, it also helps keep the atmosphere in your classroom calm and focused.

Forward planning is about being crystal clear regarding your expectations, but having plenty of ways to manage, reinforce and revisit them. It is about making sure the learning is suitably scaffolded, so that all the children feel a sense of success. Forward planning also means thinking about the timings and format of lessons and transitions, to help children stay focused and engaged.

The better prepared you are ahead of time, the more your children will feel confident and ready to learn. In addition, you will feel more secure in your ability to manage inappropriate behaviours when they do happen, and you will come across as confident in your ability to handle them.

Where the children believe that their teacher can calmly manage the classroom, this feeds into their sense of working together a learning community. In the sixth edition of my book on behaviour, Getting your Class to Behave, I explore lots of ways to plan ahead for more positive outcomes.

Setting the standards

We all know how important clear expectations are in managing behaviour: they give clarity of intent and a sense that the teacher is in control of the situation. It’s useful to remember that most children are well used to teachers establishing expectations.

Those children who attended an early years setting before school will have had several years of ‘golden rules’ being shared and reinforced. It is not that they do not know what they need to do; if they are struggling, this is because they have not yet fully developed their self-regulation skills.

Establishing your expectations is not about listing long series of rules – children are unlikely to retain them – it is about creating a shared sense of purpose. By talking through and narrating the why of the behaviours you need, we can help children understand that rules are there for a reason.

In addition, it is vital to come back to expectations repeatedly to reinforce the learning. Praise the children when they are doing the right thing, model the behaviours you ask for, and consider strategies such as having a ‘golden rule of the week’, where you focus on one behaviour at a time.

Following through

One of the keys to clarity of expectations is to ensure that you follow through on what you say (although this is often easier said than done). Ask any group of teachers what they need from the children, and they will always say that good listening is a priority.

We need ‘one voice’, so that everyone can hear what is being said, whether it is the teacher speaking or the learners. However, most of us would admit that sometimes, through sheer frustration or the pressure of time, we have ‘talked over’ a class that was not completely silent. Unfortunately, every time we do this, we send the message that we did not really mean what we said.

This is where forward planning comes in handy – think ahead of time about what you will do to get your class’s attention, and to ensure everyone listens silently. You might agree a ‘call and respond’ with the class; you could try a sound (we use a handbell in our early years setting); you might praise those children who are sitting quietly ready to listen.

The more options you have in your ‘backpack’ of strategies, the less likely you are to get defensive when issues occur, and the more likely you are to follow through.

Imaginative approaches

Young children are brilliant at entering the world of the imagination: typically, they love going along with strategies that encourage them to think creatively. Research shows that when children take on a role, this helps them manage their impulses. Imagining that they have become ‘someone else’ allows them to ‘self-distance’, and in turn supports them to persevere.

One of the times when issues often arise with behaviour is when pupils need to leave their desks to make a line, for instance to walk to assembly. Taking an imaginative approach at these times, by creating a target for the children about how you want them to move, gives them a stronger sense of focus.

For instance, you could ask them to imagine that there is a giant, asleep under the floor, and they must creep to the line so as not to wake him up. Alternatively, you could ask them to move in slow motion, like actors in an action movie. By planning ahead, you give them something specific to focus on and encourage them to work as a team to achieve it.

Planning ahead for individuals

It’s clear that many teachers are currently seeing higher levels of needs in their children, especially around emotional regulation, than was the case before the pandemic.

Some individuals are really struggling in the classroom environment, and we need to make reasonable adjustments to help them succeed. Where a child struggles with a particular situation – for instance, whole-class input – consider giving them a specific role to help regulate their behaviour. For example, if they struggle to sit still during teacher-led times, they could act as your ‘helper’, wiping the board or handing out resources.

Similarly, if you have a child who has problems with sensory overload, aim to catch them before they get to the point of melting down. Once a child is already experiencing overload, it is much harder to encourage them to self-regulate.

So, when you notice the child start to struggle, ask a teaching assistant to take them outside for some fresh air, or get the child to take something to the office for you. By pre-empting the problem and getting in front of the situation before it escalates, you will better support children’s needs and, in turn, get better behaviour in your classroom.

My key strategies for successful behaviour management

- Observe pupils’ behaviours and think about what they are communicating. This will help you figure out what they need. If children are wriggling while sat on the carpet, that behaviour suggests they need a chance to move. Get them up and active, for instance ‘acting out’ part of the class story.

- Consider the times of the day when behaviour issues most often occur, and find strategies to manage those times. Typically, some of the trickiest moments are during transitions, so it is useful to explore creative options for managing these.

- Find ways to adapt your curriculum to help you support children in learning behaviours. Be flexible about what you teach and when you teach it, to align with the children’s body clocks and their physical/emotional needs. If the children are not focused, they are not learning, so adapt to support self-regulation skills.

- Encourage the children to use imagination to support their behaviour. When children encounter a playful, creative strategy or technique, they are more likely to pay attention and consequently to behave as you need.

- Identify useful strategies for individual children ahead of time, making reasonable adjustments to help them regulate their behaviour. The standards need to remain consistent, but we can use flexible strategies to help all children reach our goals.

Sue Cowley is an author and early years teacher. Her latest book is the sixth edition of Getting your Class to Behave, published by Bloomsbury.

Talking to parents about their child’s bad behaviour

If you have to share the details of a child’s bad day at school with his or her parents, tailor your words and approach carefully, advises Debby Elley…

No one likes bad news, but sometimes it’s important that a parent knows all hasn’t been well at school today. On good days, you can hardly wait for a parent to show up so that you can share that fabulous breakthrough – bring it on, you’ve struck gold!

Then there are the not-so-good days. You can’t exactly lie, but you’re not looking forward to passing on this unwelcome information about their child that a parent needs to hear.

Take the blame

Truth is, you’re probably going to need a glass of wine to recover from it later. Still, the child’s carer will know exactly how it is. They’ll sympathise, right? Well no, they won’t. They’re far too involved to sympathise, but quite a few parents and carers will empathise, to the point where they’ll absorb the news and actually take the blame for it themselves.

If the news is broken badly, what they’ll actually hear (whether you say it or not) is ‘This is all your fault.’ The response will depend on the parent, but it can range from defensive to depressed, which is the last thing you want. Not exactly constructive, is it?

“If the news is broken badly, what they’ll actually hear (whether you say it or not) is ‘This is all your fault’”

Other parents – perhaps those who are at tipping point and beyond – will simply block out the information as unwanted and coming from ‘your corner’. They get this quite enough at home, so why would they want to hear it from you as well?

Information exchange

Any communication is a contract in which information is exchanged, so before making that exchange, it’s worth asking yourself how you want that information to be received by the other person.

For instance, if you’re about to say ‘He’s been a bit aggressive today’, are you warning of a difficult evening ahead, or are you suggesting that help is needed in tackling some tricky behaviour? What do you hope the parent will gain from the exchange?

Ask yourself what you hope to gain from the parent. Some parents might respond by bracing themselves for what could be a difficult evening, while others may well go home feeling upset that even a teacher seems to have ‘given up’ on their kid.

“Ask yourself what you hope to gain from the parent”

Of course, you haven’t given up on the child at all. But when you say ‘We haven’t had a good day’ with nothing to support that information, that’s how it can feel.

The trouble with passing on bad news without backup is that there’s nothing a parent can actually do with the information they’ve received. They can’t tell their child off, because it’s too late after the event. It may simply have the effect of making them feel downcast, all because of one lousy sentence communicated badly.

Openness and honesty

At this point, a member of school staff might protest, ‘That’s all very well, but I’m in a hurry when the parent comes along; I haven’t got time to think about tact, diplomacy, strategies and so on.’

Well, if you haven’t got any time at all, don’t say it. Email the parent instead or invite them in for a catch-up.

When broaching the topic, keep your information neutral. Use words that focus on how the child was feeling and why, then talk about how that was translated into behaviour.

To use an example involving my own son: “Alec was upset and angry today, because we had to leave the park and he didn’t want to.” Show the parent that you’ve understood and acknowledged the child’s feelings, even if they were expressed in a less-than-perfect way.

“When broaching the topic, keep your information neutral”

Suggestions

This will give them confidence that you’ve acknowledged the child’s distress, rather than purely seeking to punish them. Then go on to explain how you tackled the situation and whether you thought the strategy was successful or not.

For instance, if your response was successful, say “We found it really helps if…”. If it wasn’t, “We don’t think this approach really worked this time, and we want to try some different strategies. Do you have any suggestions for how you tackle this at home? Would you like to have a chat about it?”

If you need more information and support from the parent to get to the bottom of something, then ask for it. Contrary to popular belief, parents don’t expect teachers to have all the answers.

What we do appreciate is openness and honesty, and being asked for our views as the experts in our own children. Confident teachers will appreciate that it isn’t a sign of weakness to ask for a parent’s view – if anything, it’s quite the opposite.

Be specific

It helps to make specific requests, rather than throwing negative information into the air and hoping it’ll land in the right way. Central to this approach is making it clear that you’re in this together and expecting teamwork.

By talking about a difficult ‘situation’, rather than difficult ‘behaviour’, you take the emotion and worry out of the exchange and allow a parent the perspective they need in order to see clearly.

Your news then becomes practical and useful, rather than just baggage. You’re either going to work together to tackle something, or you’ve got a great idea that they’d do well to use themselves, which is ultimately the point of the information you’re looking to convey.

Reading between the lines

When reporting bad news, there’s also the risk that a parent will interpret it as you being at the end of your tether, or not liking their child. Believe me when I say that even the faintest hint of this is all it takes.

If the news isn’t good, there’s no need to bash them around the head to get it across. We’re finely attuned to reading between the lines, so ‘Not the best day for Alec,’ is far better than a judgemental phrase such as ‘Alec attacked another student,’ or ‘We’ve been disappointed with Alec’s behaviour today.’ He didn’t ‘lash out’ (highly emotive). He ‘felt angry’.

The very worst way to broach a difficult subject – and you’d be surprised at how often it’s used – is with the phrase ‘There was an incident at lunchtime.’ Call the police! Cordon off the area! Teachers are used to logging incidents, so this kind of phrase trips off the tongue quite easily. For most parents, it’s a word formulation they’re only ever likely to hear on the ten o’clock news.

Better strategies

My son’s school is great at broaching bad news. One of the nicest things his teacher says is ‘We’re trying to help Alec so that he has some control when he feels angry’.

Because that’s what we’re all really trying to do, isn’t it? An out-of-control child doesn’t want to feel this way. They simply don’t have a better strategy for coping with their feelings. The school’s job is to help such pupils find better ways of doing that than through physical means.

You don’t have to hide bad news from a parent. But broaching it sensitively will be your best route to finding a good solution.

Debby Elley is the co-editor of AuKids – an award-winning positive parenting magazine for children with autism. Her book, 15 Things They Forgot to Tell You About Autism, is available now, published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

How to use social norms behaviour scripts

Social norms behaviour scripts may well be the most powerful classroom management tool you ever try…

“I can see Dana* is working hard – her pen’s working furiously. I’m sure her work will be wonderful.”

This was the moment I unleashed the most powerful classroom management tool I’ve ever used: social norm behaviour scripts. Dana was a social influencer in a class I was struggling to socially influence. While the pupils were all lovely as individuals and full of character, the class’ effervescence was far greater than the sum of its parts.

As soon as I highlighted Dana’s behaviour, two pupils started to write. “Adira and Lauren, I can see your pens working furiously too.” A few more started. “That whole table too, and that one. You’re working silently and very hard, well done.”

Within 20 seconds, social norm scripts had rescued a transition that was way less than senior leader friendly.

Pithy messages

Behaviour scripts on their own are pretty handy. In a nutshell, they’re pithy messages you memorise and use for dealing with tricky behaviour issues with calm authority and consistency. Up to this point, I wasn’t bad at classroom management but my mouth wouldn’t always find the right words when needed and I’d end up a waffly mess.

Using behaviour scripts, I dealt with issues far better. For some pupils though, the scripts were water off a duck’s back. That’s when I stumbled across social norms – my comment to Dana was my first script that included them. The class and I never looked back.

Peer culture

So what are social norms? Essentially, they’re a shared understanding of what you should and shouldn’t do in a social situation or group. Whether explicit or unsaid, they’re incredibly powerful. Think about the last time you entered a library. There probably weren’t any ‘be quiet’ signs up, but you knew the expectation.

And think about how eyebrows raise when someone doesn’t buy a round of drinks when it‘s their turn. These are social norms in action. Following a group’s social norms signals your belonging. Run against them and you risk exclusion.

Belong and comply

Social norms are powered by people’s resolute desire to belong to and comply with their social groups. Sometimes people aren’t aware of the norms – the idea is you tell them and they begin to comply.

Policymakers have used them to reduce households’ energy use by sending ‘your neighbours use less energy than you’ letters and even reduced the amount students drink on a night out by putting up ‘most students only have a couple of drinks’ posters.

Social norms hold great power in classrooms too. In The Hidden Lives of Learners, Graham Nuthall describes how peer culture makes or breaks a learning environment. If there’s a choice for pupils to follow peers’ or teachers’ norms, there’s only going to be one winner and it’s not going to be the teacher.

Share positive norms

It’s almost impossible to impose teacher norms when peer culture is strong or there’s a gulf between teacher and peer norms. I admired Dana for her strong will and social influence even though to her I wasn’t worth too much attention.

So rather than fight her or the strong peer culture, I decided to embrace their collective vim and vigour. Instead of advertising the social norms I wanted to reduce, I resolved to share positive norms through behaviour scripts.

Because people have a strong desire to belong and conform and because I was giving the class the information to be able to do so, it worked. It worked so well, in fact, that my class became a joy to teach. They gained a sense of collective focus and their work improved immeasurably.

Transitions became easier and off-task behaviour diminished. All this while they retained their individual character and close bonds. Since then, I’ve used social norm scripts with countless classes and colleagues and the outcomes are always the same: behaviour improves and class cultures get stronger.

Concrete and specific

Social norm scripts are relatively easy to craft by adhering to a few key principles. First, you need to identify the target behaviour that you want to encourage. It sounds obvious, but if you don’t know what you’re looking for, your pupils will have no chance. You need to be concrete and specific.

Children want to belong and conform but they need to know how. Consider how the behaviour looks, sounds and when and where it might happen.

For example, you might expect whisper voices, open books and moving pencils within 30 seconds of a writing task transition. When talking to the class, you might wish to see forward-facing eyes and shoulders, raised hands for verbal contributions and hear no other voices except your own.

Of course, these are generic but you can adjust them to your own style and your pupils’ needs.

Descriptive and injunctive

There are two types of social norms – descriptive and injunctive. Descriptive norms are just as they sound: they describe what is typically done. They are also the easiest to construct. Simply highlight the target behaviours (italic, below) that are being done by the majority or key individuals (bold, below).

For the writing task and teacher-talk target behaviours, you might write them as follows:

- Thank you to the middle tables who are showing me they’re ready because their eyes and shoulders are facing me.

- I can see Dana’s book is open and her pencil is working furiously. And Adira’s too. And the whole of Mohammed’s table. Thank you.

Injunctive norms are important because descriptive norms on their own can have unintended effects. While the heaviest student drinkers in the social norm campaign I mentioned above drank less, teetotallers and light drinkers ended up drinking a little more to meet the norm.

Injunctive norms (in bold, below) can negate these boomerang effects. They describe what the majority approve or disapprove of and can be added to the end of our descriptive norm scripts:

- Thank you to the middle tables who are showing me they’re ready because their eyes and shoulders are facing me. You’re helping others by being so quick to get focused.

- I can see Dana’s book is open and her pencil is working furiously. And Adira’s too. And the whole of Mohammed’s table. Your class is proud of how hard you’re working.

Build slowly

At first, it’s better to have a few social norm scripts that work than loads that don’t. You don’t want to overload yourself and you can build slowly on your success. The trick is to make them as pithy as possible – too wordy and they’ll get lost in the moment and stall on your tongue.

Next you’ll need to memorise your scripts. Rehearse them in a mirror until you find the sweet spot of automatic clarity and calm authority. This bit is excruciatingly awkward but if you skip it, you won’t get the most out of your hard work.

Finally, use them consistently. The more your children hear the scripts, the more they’ll recognise them as cues they can easily respond to.

The really juicy secret to let you in on is using social norm scripts to create new norms. If your class is unfocused and unsettled, a few judicious scripts that highlight one or two individuals – even those without a lot of social influence – will quickly get the majority on board. Enjoy crafting them and enjoy their results.

* All pupils’ names changed

Dan Whittaker is a lecturer at the University of Worcester. He taught in primary schools across the West Midlands and specialises in computing and classroom management. Follow him on Twitter at @class_whisperer. Visit his website here.

Helping pupils learn from their actions

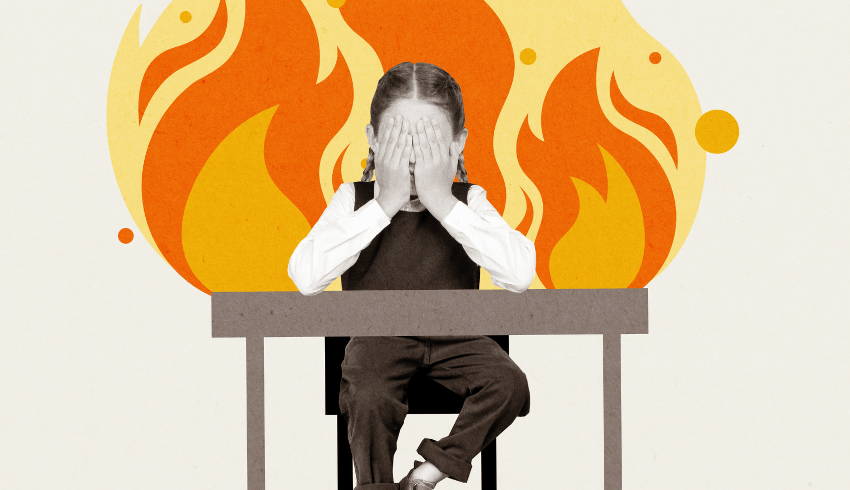

Focusing on punitive measures instead of teaching children self-control is doing untellable damage. So why not help pupils understand their feelings instead?

I regularly hear that because I am anti-punitive regarding behaviour in schools, I must let children do whatever they want. But this is not even close to being the case. I have high behaviour expectations, no different from any other educator.

But I also understand that threatening punitive consequences in order to get children to meet them is rarely effective.

Now, there will of course be some children who do respond to punitive measures. However, I am interested in creating a culture of safety and quality learning, and that requires more than just getting children to conform.

There were times early in my career when I did take a more disciplinary approach, but I found that it almost guaranteed that behaviour would deteriorate. Not that I claim to have perfect behaviour now; children aren’t robots, and when they express themselves, they will sometimes get it wrong. My job is to help them learn from their mistakes.

The shame spiral

Preventing self-expression and forcing children to suppress their feelings because they are ‘bad’ can be dangerous. Failing to separate the feeling from the behaviour is as far from what we need to be doing as we can get.

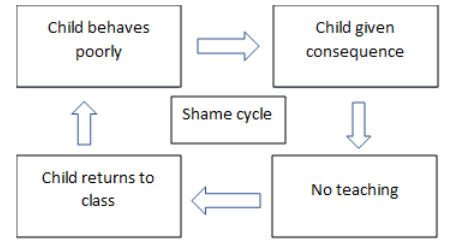

It is why zero-tolerance approaches are sending many children into shame cycles (see figure 1), and why we are creating young adults who are both scared of their feelings and unable to control them.

If we have never taught children to understand that it is feelings that cause behaviour, then how can they learn to control their feelings?

Trending

We should be teaching the child self-control, and this means learning from their mistakes; and, if they do something wrong, expecting them to put it right.

I favour logical consequences because that is what happens in real life.

In the real world, verbally lashing out at your partner and then going and sitting in silence in your bedroom for half an hour doesn’t make it all go away.

Actions have consequences, but actions also need to be repaired. In many schools, the consequence is more about payback.

Punishment without repair doesn’t prepare children for life after school, and it compounds the shame they already feel.

With enough repetition, ‘I have been bad’ becomes ‘I am bad.’ It creates an inevitability for some children about their future that we should be doing everything we can to prevent.

Behaviour policy in schools

Even with so much in the news about vulnerable pupils, the continuing impact of the pandemic and the widening socio-economic divide, there are those in education who still favour a zero-tolerance approach.

The language used in these approaches is very often focused on training behaviour; with the adult modelling it for children to copy, rather than teaching it so children learn how to change.

This ‘us and them’ is a dated approach to education. ‘Doing to’ rather than ‘doing with’ will always exclude a minority of pupils whose parents or carers haven’t taught them to behave in their formative years.

Systems are important, especially in large schools where they play a vital role in consistency. But the system can’t replace the human element in teaching and relationships.

In too many cases, the system dictates that when a child doesn’t follow the rules – whether because they won’t or can’t doesn’t matter – the answer is a punitive response.

This will often follow a set pattern, possibly associated with codes like C1, C2 and so on:

- Reminder of expectation

- Warning

- Name on the board

- Tick next to name, probably signifying a sanction

- Asked to leave the room or removed by a member of staff

The problem is that each punitive step is unlikely to deter a dysregulated child; therefore, teachers will withdraw them pretty quickly. Rattling through these consequences leaves them with no place to go.

Behaviour management strategies for primary school

Consequences perform a vital role in using behaviour as a learning opportunity. If they are part of the teaching, they have an important role to play.

When consequences give no repair opportunity, they are meaningless; if we design them to appease a system or to be a deterrent to others, then they will have little impact.

Therefore, whenever we issue a consequence, we should ask three questions:

- Does the consequence match up to the behaviour and take motive into account?

- Can the consequence teach the child what the behavioural mistake was? Does it help them to understand what to do next time?

- Does the consequence teach the child how their action has affected others and motivate them to behave differently in the future?

If an honest answer to these three questions is no, then the consequence isn’t fit for purpose.

There will, of course, always be a large cohort who are driven by the need to please adults and therefore do the right thing. It is easy to point to these children and deem the system successful. But these pupils would obey the rules under any system.

They have the necessary skills and intrinsic motivation. This means they don’t require the fear of a deterrent or extrinsic reward to behave well.

Behaviour inclusivity

A minority of children will never be successful in systems like these. This is because they don’t have the necessary skills and because they direct their motivation towards matters like survival.

If the child is in a shame cycle, then poor behaviour will be what they know and what people expect. It stands to reason, then, that they will behave poorly.

Ignoring the needs of this minority isn’t inclusive. Repeating the same process with the same children isn’t inclusive.

Encouraging children’s parents to take them to another school because this school’s expectations will be too much for them isn’t inclusive.

Inclusive means all children. It means an approach to consequences by which we teach every pupil to cope effectively within our school system.

This requires us to look at how we use consequences. If we apply these approaches consistently, we equip children to manage their own behaviour. And, importantly, we don’t get stuck in a shame loop.

Graham Chatterley is a former school leader and author of Changing Perceptions: Deciphering the language of behaviour (£17.99, Crown House Publishing). Read more about positive behaviour support.

Strategies that work better than behaviour charts

How do you balance the complexity of pedagogy with the social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) needs of every pupil? Do you reflect on why you teach? How does this affect your approach to classroom behaviour?

It’s a lot to think about. Your answer might centre on measurable academic progression, a wider view of the child’s overall healthy development, or maybe it includes considerations of your own wellbeing.

The complexity of the issue may also lead you to accept established ‘behaviourist’ methods. Rooted in 1940’s psychology, this approach shapes surface behaviours by rewarding and punishing. It is seductively simple.

For example, zone boards. These are the various public displays where pupil names will be moved up or down a scale depending on behavioural criteria set by adults.

A move up (possibly to the ‘green zone’ or ‘sunshine’) is intended to reward the child by recognising compliance, and a move down (often to the ‘red zone’ or ‘rain cloud’) is a public punishment for non-compliance.

Don’t get me wrong, I once used these with great enthusiasm. But through experience, I have found they really don’t work, especially for the children who need them most.

These are the children whose names keep appearing on the red zone time and time again; the repetitive pattern shows us that this system does nothing at all to help pupils build the skills they need.

Behaviour management in schools

According to child psychologist Dr Ross Greene, ‘kids do well if they can’ and we know all children have a biological imperative to feel safe, to belong and learn to some extent.

Children will also do their best to adapt, even sometimes at a cost to their own healthy development and learning. Zone boards and the like therefore also have a wider and less visible impact on the class, such as producing children who are complying out of a fear-based motivation to avoid the shame of the red zone, which ends up depleting both their relational trust and academic potential.

Another casualty of the zone board is the child who learns to engage just for the extrinsic rewards; they are likely to get bored and then crave reward inflation, reducing their potential to develop a more robust, intrinsic love of learning.

Nuanced journey

More widely, the simple application of rewards and punishments teaches children not to think but to comply. This might make them more vulnerable to grooming or condition them into complying only when being checked, (like adults who speed between cameras!).

We should, instead of these behaviour charts, try engaging with developmental needs through relationships, which build collaborative value-based learning. A chart can never do this.

You don’t need it; you are the resource. It is, however, a nuanced journey rather than a tool, and requires an open, curious, non-judgmental mind, an open heart and a capacity for reflection and the longer view. Dr Bruce Perry’s ‘3 R’s’ of Regulation, Relationship and Reason is a good place to start.

Behaviour management strategies for primary school

Begin with emotional regulation: are you emotionally steady with enough capacity to approach challenges – both for the pupil and yourself? You need to be calm and thoughtful to get a calm and thoughtful child.

Next, you need to interpret the state of the student’s emotional regulation, and prioritise re-establishing ‘felt safety’ and social engagement through your relationship with them.

This is a nuanced process but once relational connection and trust is founded, you can then move onto reason with a greater capacity for progress.

Reason is where skill building happens collaboratively. If you have taken a child through the cycle of ‘rupture and repair’ this meaningful connection will give you a better opportunity to scaffold development of new or unsteady skills.

Make sure to ask yourself if you are targeting the right type and amount of challenge for this child in this moment.

So, rather than relying on the superficial and fragile application of rewards and punishments, we should ditch the zone boards and start to invest in a sequenced approach to behaviour.

We’ll likely see better outcomes, and might even find a deeper and richer answer to the question ‘Why do I teach?’.

Heather Lucas is a SEMH specialist supporting primary schools, based in West Sussex and Hampshire. This article is inspired by the Facebook page ‘Heidi and Me. Our Neurodiversity Journey.’ Follow Heather on Twitter @HLucas8.

Dealing with low-level disruption

Worried about repeated low-level disruption? Hearing whispers about behaviour in your classroom? It’s time for a new start with these simple behaviour management strategies for primary school…

Strategy 1: Positive behaviour spotting

It’s easy to feel your patience slipping when you hear negativity from ‘mood hoovers’ about how they feel about the behaviour in your classroom. But remember that, you, as the adult within your classroom, create the atmosphere, affect the day and influence your children. You can achieve the classroom atmosphere that you desire by positive behaviour spotting.

When a child is showing the undesirable behaviours that are causing disruption to others, instead of using negativity or consequences, praise somebody within your class that is showing the positive behaviours that you want, such as, “Well done for putting your hand up”.

As you get to know your children better and develop stronger relationships, you will begin to be able to notice when your ‘eager’ child is getting fidgety and become more proactive in your approach by praising them for their positive behaviour before the shouting out even occurs.

Children that shout out want to show you that they know the answer to your question. They want to please you by giving you what they want. There’s no deliberate act of wanting to disrupt learning. By positive behaviour spotting, you aren’t having to give negative attention, which neither you nor the child want.

Strategy 2: Keep communicating

If the child that is shouting out is causing disruption to your classroom, it is really important to focus on communication with all involved.

This includes speaking to previous class teachers who may have, more than likely, experienced the same behaviours and may have information about strategies that have and haven’t worked. This knowledge might be invaluable to you.

Look at communication with the child too. Use ideas such as the ‘5 x 2’ strategy, where you let the child lead the conversation for at least two minutes, five times a day. It’s strategies like these that ensure you will have positive interactions with pupils. Sometimes, in the busy life of a school, you have to set time aside to ensure this is a feature of the day.

Parents

Don’t forget the parents either. When communicating with them, make sure that you separate the child from his or her behaviour. Focus on the positives – not a stream of negatives – and build relationships early.

It’s important to have an objective to your conversation and avoid jargon and information overload. Be aware of family dynamics too – who is the person that you need to communicate with?

Communication is one of the key tools in education. We don’t always get feedback when communication is good, but you will certainly get told when it isn’t. Positive change happens when all parties are working towards the same objective, making it vital that your communication is sound.

Be aware of barriers. Can you use alternative methods of communication, such as email, the phone or home-school book?

Strategy 3: Target your support

If a child continues to struggle with a particular aspect of their behaviour, whether it’s disruptive lunchtimes or shouting out, you need to pinpoint support that will help to modify it.

You might want to consider some additional activities that will enable children to focus on their behaviour, with adult support. Plan this in exactly the same way as you would plan an intervention:

- Assess the need for the intervention. How often does the behaviour in question happen, and what are you trying to achieve? Obviously you want to reduce the frequency of behaviours to zero but what, realistically, will be your objective?

- Plan your activities. This might take the form of a six to eight week block of work, focusing on the specific behaviour.

- Complete your block of interventions. You may want have a specific focus on behaviours by discussing events in between your intervention. Some examples of questions you may want to ask include: where were you when the ‘shouting out’ occurred? What did you say, and in response to what? What did your teacher say and why do you think they said that? Did you stop or continue? What was the consequence?

- Ensure that you review each session with the child. This could be through the simple use of a RAG (Red, Amber, Green) rating by the child, then the adult that’s completing the intervention.

Success

There are plenty of options to help you tighten your grip on low level disruptive behaviour within your classroom. As long as your relationships with the children continue to develop, you’re bound to see success.

The key thread running through all three of these behaviour management strategies for primary school is support. By keeping that as your focus, you can continue to develop an atmosphere within your classroom that ensures the adults have a positive impact on the lives of the children and equip them for the subsequent stages in their school life.

Tracey Lawrence is the author of Practical Behaviour Management for Primary School Teachers (£16.99, Bloomsbury). Visit her website and follow her on Twitter at @behaviourteach.

Get back to September behaviour in six easy steps

Coming out of the ‘honeymoon period’ with a class can feel a little like you’ve lost control, but here’s how to make getting back to September standards completely manageable…

The ‘SIMPLE’ guide to managing behaviour gives you a handful of strategies to implement, even if things have gone awry since the start of the year. These are behaviour management strategies for primary school that work, as long as you use them consistently:

- Systems

- Implementation of class rules

- Managing low-level disruption

- Pace

- Language

- Expectations

Systems

Setting up systems in the classroom is crucial to successful behaviour management and it’s never too late to implement them. Children respond well to systems, but setting them up does take some planning. Examples include:

Reward systems – find one that your class will respond to and put it into place. Be consistent – recognise behaviour choices that are in line with the class or school rules.

Seating plans – these can guarantee constructive learning takes place, as well as ensuring that distractions are kept to a minimum. Change seating plans each half term to give children a chance to work with different peers.

Morning routines – have something set up that can be done daily and enables the class to start the day in a positive, calm way.

Sanctions – reward systems are important to create, but so are sanctions. Children need to understand that there are consequences to their behaviour choices. Follow the school policy and follow through with a sanction once you’ve given it.

Implementation of class rules

Class rules are important for adults and children alike. They ensure boundaries are set and adhered to, as well as providing a consistent approach for both teacher and TA. Refer to the rules frequently so that you can remind children of the behaviour expectations. Use them when explaining sanctions so that children understand why they are receiving it.

When creating class rules, ensure that the language is positive, eg ‘We put our hands up if we have something to say’, rather than ‘Don’t call out.’ Revisit these rules during circle times throughout the term, refining and improving them as necessary.

Managing low-level disruption

Low-level disruption is one of the banes of teaching life. A little like a cold, it starts off with a single case, but can become contagious very quickly. You have to manage it consistently well. Left untreated, it impacts the learning of everyone in the class, but also wears you out very quickly.

The best way to fix the contagion is to be ruthless in your treatment of it. If a child talks while you’re talking, stop and wait. If a child is wandering around distracting others, ask them why and remind them of your expectations.

Don’t let low-level disruption win. If you’ve been letting it run riot in your classroom, you’ve still got time to salvage the situation. It’ll be hard, but it’s worth it. Be consistent and you can effectively treat the epidemic; the classroom will be a happy and healthy learning environment once again.

Pace

If the pace of your lessons is slow, children will become bored and make poor behaviour choices to amuse themselves, thus impacting their learning and their progress.

Keeping your lessons pacy will ensure children stay on task, giving them less time for distractions. Keep the children on a clock, eg ‘You have ten minutes to finish the task.’ They respond well to this approach and it keeps the pace up. Counting down from ten to zero also works well and keeps the children focused on you.

Language

Keeping your language simple is key to good behaviour management. Don’t lecture children about their behaviour, as they’ll switch off. Deal swiftly with the behaviour that’s being displayed and without a lot of conversation.

Children are experts are dragging adults into conversation in a bid to distract them from giving sanctions; don’t let yourself get sucked in.

If something needs further investigation, arrange a time to discuss it later – the middle of a lesson is not the time to discuss Molly pulling Lucy’s hair at lunchtime. If it’s simply the case of Rashid flicking Alfie’s ears, give him a quick reminder of your expectations or move him away from the temptation altogether.

Expectations

High expectations are essential to successful classroom management. The bar for behaviour needs to be set at the start of the year and it needs to be high.

Children must rise to meet your expectations. If you expect a high standard of behaviour, you’ll get it. If the children get away with little things, you can kiss goodbye to a well-managed class and say hello to low-level disruption.

Keep your expectations high all year. You’ll be able to relax a bit once the autumn term is over but the children need to remember where that line is, always.

How to help children manage their own volume levels

If your ears are ringing and your throat is sore, perhaps it’s time to change your tactics…

Gestures, hand signals and facial expressions are a great way to communicate. They show children that you can ‘say’ an awful lot, without even opening your mouth. The key is to figure out strategies to keep the overall volume in check, and to encourage children to manage their own noise by themselves.

One handy method is to get the children to experiment with different noise levels. If they can adapt their volume for ‘paired voice’, ‘group voice’, ‘classroom voice’ and ‘outdoor voice’, then hopefully they will be able to manage ‘Miss has got a headache voice’ when the need arises.

Electronic traffic lights

Another good idea is to use a set of electronic traffic lights with an alarm that goes off if the volume gets too high. As the lights change from green, to amber, to red, the children have a visual warning that their noise levels are increasing.

For a homespun noise-o-meter, stick a dial to the back of a shoebox, and then use a paper fastener to attach an arrow. Move the arrow around as the volume levels increase, and challenge the children to stay out of the ‘danger zone’.

Motivation

One of the very best ways to get children to keep their noise levels down is to give them a strong motivation to do so. Bring in some animal visitors as a great reason to keep quiet instead. A reading dog that comes to your class; some chicks to hatch out; a pair of guinea pigs whose delicate ears might get hurt if the children are too loud.

And if the thought of cleaning up after a class pet doesn’t appeal to you, I have the perfect alternative. You know those pom-pom-shaped bugs given out as promotional gifts – the ones with the sticky feet and the long ribbon tails? These are ‘Quiet Critters’.

They live in a soundproof jar or tank, and are very shy and nervous, so they only come out to play when there is very little noise. Quiet Critters love to sit beside the children and learn with them, but if the volume gets too high, they scurry back to their home.

Of course, noise is all part of the job when it comes to working with children, and it wouldn’t do for them to be too quiet for too much of the time. Because as the saying goes, silence is golden, unless you have kids. Then silence is just plain suspicious.

Sue Cowley is an author and teacher trainer.