GCSE standards – Why teachers in the US enjoy more freedom

Teachers in the US often enjoy a degree of professional agency their UK counterparts can only envy, argues John Lawson

- by John Lawson

The theologian, St Thomas Aquinas, once defined the seven sacraments as ‘outward signs of an inward grace’.

It’s a brilliant definition that aptly describes any graduation ceremony. The communal razzmatazz of airborne caps, gowns, scrolls and speeches externally symbolise the inner achievements of those who toil in our educational vineyards.

American families rightly celebrate their children’s achievements when they complete a four-year high school programme from the age of 15 until 18. Most parents aren’t celebrating outstanding successes in public examinations, since the majority don’t take any. Instead, they’re acknowledging the character it takes to show up for school regularly and give one’s best.

An annual PSAT test will give children a national STEM ranking, but this doesn’t directly affect one’s graduation. (Not that children’s worth should be reduced to academic grades.) To actually graduate, students require a minimum ‘D’ grade (60%) in every class they’ve taken throughout the four years, along with acceptable attendance, community service hours and a good disciplinary record.

Most American schools offer three tiered programmes: Advanced Placement (externally assessed), Honours, and Regular. If students undertake rigorous AP courses, their grades, behaviour, and effort must be exemplary. Should they fall behind, they must quickly catch up via extra work or else drop a level.

American parents rarely oppose streaming, because they believe schools must identify and nurture their most academically able students if America is to remain a global superpower. Today’s future scientists, surgeons and senators are therefore encouraged from an early age.

Places at society’s top tables may be theoretically open to everyone, but in practice they’re earned by those who diligently pursue their own ‘American dream’ with an effective gameplan.

The US system isn’t flawless or entirely stress-free, but it does serve families well – and we in the UK could learn from some of its strengths.

Seeking honours

Americans broadly accept that only 25% of students will go on to study at the highest academic level. Creating a more equitable world requires us to address a few universal realities more honestly – including the fact that whatever system we operate, some children will always be ‘book-smarter’ than others.

Seen in this light, American high schools are where the rigour of British grammar schools is incorporated into a comprehensive model. Among children not yet at AP level, parents will often remain ambitious for them to get into honours classes. About 40% succeed, with these hard-working students then going on to apply to reputable universities.

That leaves around 35% of teens taking regular courses that provide a flexible, collaborative and relaxed pace of learning. The emphasis on regular classes allows students to acquire a solid foundation in the basics of core subjects.

Subject teachers, supervised by administrators, will determine and adjust the curriculum for these classes, with diligent students often upgraded into honours classes. Undergraduates can also be upgraded to higher-ranked universities after two years.

Thanks to this graduation system, the 18 years I spent teaching in Florida gifted me an autonomy denied to most UK educators. I was obligated to teach church history and global ethics, but what we covered was my choice. US teachers are encouraged to create and submit their own honours and regular courses to their principals.

All assessments, including final exams, are entrusted to teachers, rather than academic boards. The tremendous benefit here is that teachers are able to select material that engages their students – and if possible, will bin the boring bits. When teachers teach to their passions, students learn far more.

The GCSE straitjacket

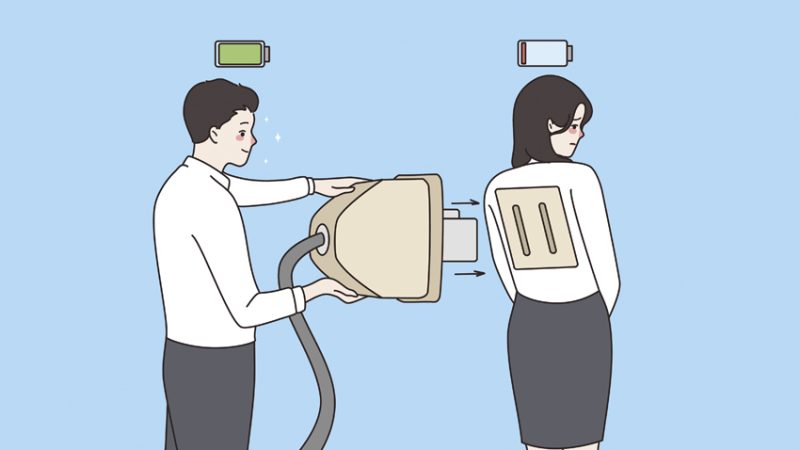

Conversely, teachers in the UK will often observe students struggling to cope with the straitjacket of GCSEs, but lack any recourse to options that will alleviate such pressures and make courses more relatable. American educators have the freedom to honour the ‘spirit’, rather than the ‘letter’ of academic laws.

My greatest concern for UK students falling short of GCSE standards is that they’ll become disillusioned or disruptive and stop trying. Many teenagers leave school with nothing comparable to an officially recognised graduation certificate that symbolises and celebrates their abilities and best efforts.

As I’ve seen first-hand, internal assessments enable teachers to respect, cultivate, and reward the emotional literacy and resilience of their students, as well as the cognitive skills measured by traditional exams.

John Lawson is a former secondary teacher, now serving as a foundation governor and running a tutoring service, and author of the book The Successful (Less Stressful) Student (Outskirts Press, £11.95); for more, visit prep4successnow.wordpress.com or follow @johninpompano