Computer Games Could Prepare Students For A Valuable Career – So Shouldn’t Schools Acknowledge This?

Help young gamers get to the next level, says Sal Mckeown

- by Sal McKeown

‘Creativity has almost been driven out of the school curriculum,’ says David Eley, director of learning, computing department, and ICT curriculum leader at Shire Oak Academy in Walsall. ‘There are so many objectives for lessons now, and fewer opportunities for creative activities but young people respond best to things they do and make. I haven’t come across anyone who doesn’t enjoy gaming.’

David Figueira would agree. He has been gaming since he was four years old: ‘My dad introduced me to Sega’s Dreamcast and I was intrigued that I could make things happen on the screen. It opened up a whole new field of entertainment.’

Aged six, he graduated to adventure games played online and has been immersed in the video game world ever since, but now that he is studying for A-levels at New College Swindon his family are concerned at the amount of time he spends gaming.

Rich career opportunities

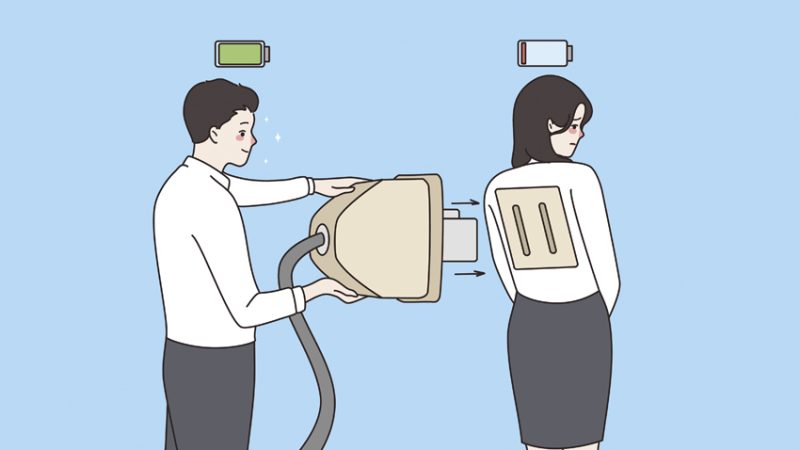

Perhaps this typifies the generation gap. While parents and teachers see gaming as an entertainment and a distraction from ‘real’ work, it’s actually an activity that is rivalling sport in the creation of new jobs, not just for players but also for designers, animators, testers, audio engineers and writers.

In 2016 the Department for Culture, Media & Sport reported: ‘British films, music, video games, crafts and publishing are taking a lead role in driving the UK’s economic recovery. The figures show the sector growing at almost twice the rate of the wider UK economy – generating £9.6million per hour.’

While schools are squeezed for time in art, music, dance and drama, these creative subjects develop essential qualities for many of the new jobs. Kate, a student at Shire Oak Academy, is a keen gamer. As well as studying computer science, she is taking a GCSE in photography while her friend Jess is studying music and is currently composing a soundtrack for a video game.

High-stakes rewards

Professional gamer Ryan Graham, 22, aka Doomsee, thinks this is an excellent choice: ‘Every game has music and it is someone’s job to create that recording.’ He has a degree in visual effects and 3D and earns a living by playing in competitions and creating content for YouTube with highlights from tournaments, montages of different shots and curating some of the mishaps and ‘funny moments.’

He was one of three professional gamers at the recent eSports Tournament Grand Final organised by Digital Schoolhouse and powered by PlayStation. This was part of the London Games Festival, designed to promote job opportunities in the video games and interactive entertainment sector.

eSports are big business. They offer multiplayer video game competitions, usually between professional players, and with the advent of the streaming video service Twitch TV they are attracting massive audiences. Major tournaments fill huge stadiums and the prizes rival, or even exceed, those in traditional sports. The Wimbledon Tennis Final netted the singles winners £2 million – but the 2016 final of the game DOTA 2 saw a record prize pool of $20.1million, with $9 million awarded to the winning team.

Practice and communication

Mike Ellis, 21, aka Gregan, earns money through playing in tournaments and is also a ‘shoutcaster’, providing a commentary on contests. He credits Ashcombe School in Dorking and Reigate Grammar with developing his skills in public speaking. Now in his third year of medical school, he is unlikely to become a doctor. ‘At school, they used to say we should prepare for jobs that didn’t yet exist. That is what I plan to do.’ He is the right generation to research sports performance and gaming.

Rymel Hanson, aka Bipod, is the old man of the group at 25. He has a degree in sports science and a job as assistant manager in retail. He feels he came late to the party. ‘Good gamers, like good athletes, start very young but I was in secondary school when gaming exploded.’ However, while gaming is not his main source of income, he has had some unforgettable experiences, such as being flown to Hollywood for the Rocket League finals.

It seems that parents and teachers who say, ‘Gaming won’t get you a job’ are wrong. So, what can schools do to prepare students for this new world? The professionals felt that schools should make sure students were confident users of technology and provide opportunities for them to get to know games at a deeper level. As professionals, they should expect to spend five or six hours a day practising. This might seem excessive to teachers and parents, who would perhaps be more accepting if that time were spent on sports or music.

Pupils from Shire Oak Academy in Walsall added to the list. They felt that schools should provide opportunities for students to improve their coordination and reflexes, encourage teamwork and help them to become better communicators. ‘If you can’t talk to your team during a match, you’re never going to win.’

Gaming within the curriculum

At Shire Oak Academy David Eley has been responsible for introducing gaming in the school and runs an ICT club on a Monday where students can play games on the Xbox, work with Lego Mindstorms, Yobot and Spytanks, Raspberry Pi and Pi2go and Initio; while in computer science lessons, Year 8s evaluate games in class and are using Microsoft Kodu to make simple ones of their own.

Many of the students have the experience of sitting at home gaming on an PS4 in their bedroom but schools offer a social aspect, a forum where they can discuss and formulate ideas.

Shahneila Saeed, Programme Director for Digital Schoolhouse, at Ukie – The Association for UK Interactive Entertainment – wants to encourage home grown talent. She points out that UK development studios are behind many of the world’s leading games including RuneScape, Farm Heroes, Batman Arkham, Football Manager, Grand Theft Auto and Lego Star Wars.

‘Video games is an exciting sector, full of constant innovation and can be an extremely rewarding experience for all those involved,’ she observes. ‘The key thing to remember is that it is a broad industry, and not everyone has to be a programmer. Whatever your passion and interest, there’s a job for you.’

Sal McKeown is a freelance special needs journalist and author of Brilliant Ideas for Using ICT in the Inclusive Classroom (Routledge) and a book for parents, How to help your Dyslexic and Dyspraxic Child (Crimson Publishing).