AI in education – Expert tips for using it in your classroom

There’s lots of big promises surrounding AI, but in reality it’s already changing the way we teach. Get on board with this advice from fellow teachers…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Lots of educators are already using AI in education to save time and automate some of the duller aspects of the job. (Report writing, anyone?)

In fact, according to the survey tool Teacher Tapp, four in ten teachers are already using AI in their schoolwork. Educational technologist and former deputy headteacher, Mel Parker, predicts that with budget cuts and teacher shortages, AI in 2024 will become “an essential tool to support teachers in their day-to-day role”.

Here’s how you can use AI in your classroom to save time and improve your teaching…

Time-saving AI teaching resources

Lyndsey Stuttard sets out some practical and potentially effective uses for AI within your classroom…

Not all schools will benefit from using AI. For many, there can be multiple, much more pressing issues to consider. However, if you have the capacity, try designating a member of staff to research possible AI applications within the context of your school’s needs. Here’s a few ideas to get you started…

Discover alternative teaching perspectives

Many teachers can feel out of their comfort zone when approaching new themes as part of their school curriculum and syllabus planning. For example, at our school, teachers were tasked with rewriting the entire Lower School curriculum to ensure that each unit included a theme from the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

In an instance like this, you can use AI tools in order to highlight anything you may have missed. By entering the new criteria and unit into ChatGPT, you can quickly see if there are any additional topics that might be relevant for specific age groups, for example.

Provide real-time learning feedback

Sadly, we’re not always able to provide as much feedback as we’d like for homework or assignments. The tool Quizlet helps students practise their vocabulary and make flashcards.

Quizlet’s Chat Robot tests students on the meaning of a term, and if a student submits an incorrect answer, that answer is analysed.

Instant feedback is then provided to explain the term in more detail and help the student understand where they may have gone wrong.

Support reading comprehension

Another recent addition to Quizlet is a set of AI features aimed at making vocabulary learning more accessible and engaging.

Via the app’s Magic Notes tool, students can insert longer articles into Quizlet and receive a summary or outline of the key points. This saves teachers time while supporting students who might struggle with comprehension tasks.

Create revision plans

AI tools can be highly beneficial for students who find it difficult to structure their own learning. Students can use ChatGPT to create workflows, study strategies and even revision plans that work for them, making a potentially overwhelming task much more manageable.

Tap into unfamiliar topics

AI can aid teachers in delving into new, hitherto unfamiliar teaching topics. We sought to incorporate the aforementioned Sustainable Development Goals into our curriculum, but are by no means experts in each of the Goals.

How, for example, should we make gender equality more accessible to a five-year-old? AI tools can serve teachers as helpful ‘ideas generators’ by providing an introduction to a topic and recommending an age-appropriate learning activity, or by suggesting which resources could best facilitate said learning.

Lyndsey Stuttard is a digital teaching and learning specialist at ACS International School Cobham.

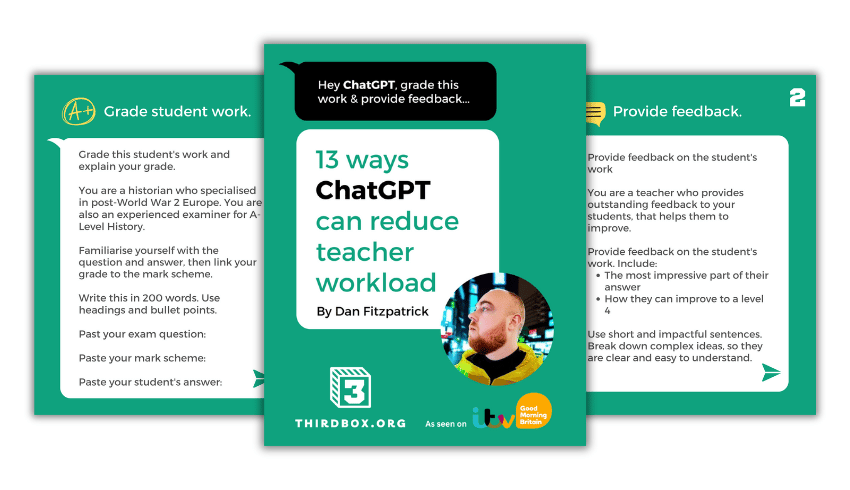

13 ways ChatGPT can reduce teacher workload

This free guide from Dan Fitzpatrick covers using ChatGPT to:

- Mark work

- Provide feedback

- Model answers

- Create a unit of work or lesson plan

- Create questions/lesson booklets

- Make a presentation

- Write reports and parents’ evening notes

- Create a curriculum intent document

Dan also offers a ChatGPT Survival Kit video course.

AI lesson plan generators

Picture this: no more late nights drowning in paperwork. Instead, just a trusty assistant crafting lesson plans at the speed of light. Say goodbye to monotony and hello to more coffee breaks with the new raft of AI lesson plan generators that are popping up around the internet.

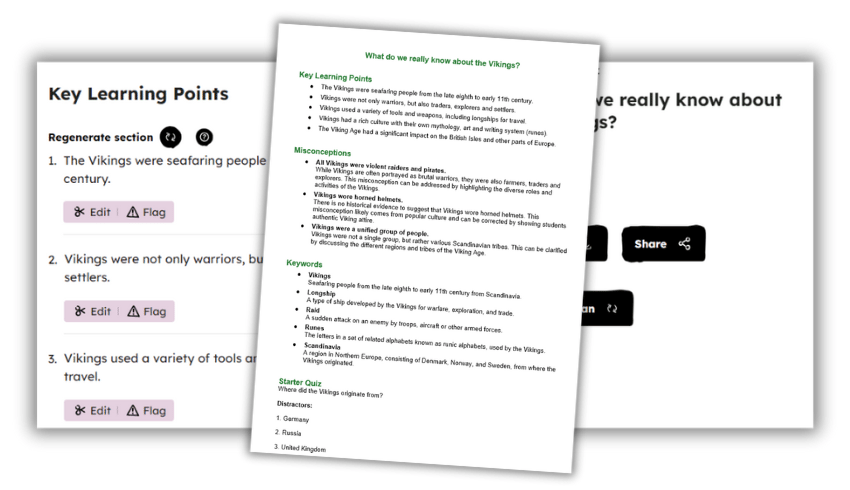

One such example is Oak AI Experiments, which is supported by a £2 million investment from the government. This free tool allows you to:

- create and refine keywords

- share common misconceptions

- outline essential learning objectives

- build an introductory and exit quiz

Here we’ve asked it to generate a KS2 history lesson under the title, ‘What do we really know about the Vikings?’. Beware though, as Daisy Christodoulou points out, AI is prone to making factual errors. For this reason, it’s important to check the outputs they generate.

Why not give it a go yourself? Cheers to stress-free planning! You can also experiment with generating quizzes for your students. The AI-driven tool generates answers and distractors in a format that you can share or export.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak commented on these AI tools, saying: “Oak National Academy’s work to harness AI to free up the workload for teachers is a perfect example of the revolutionary benefits this technology can bring.”

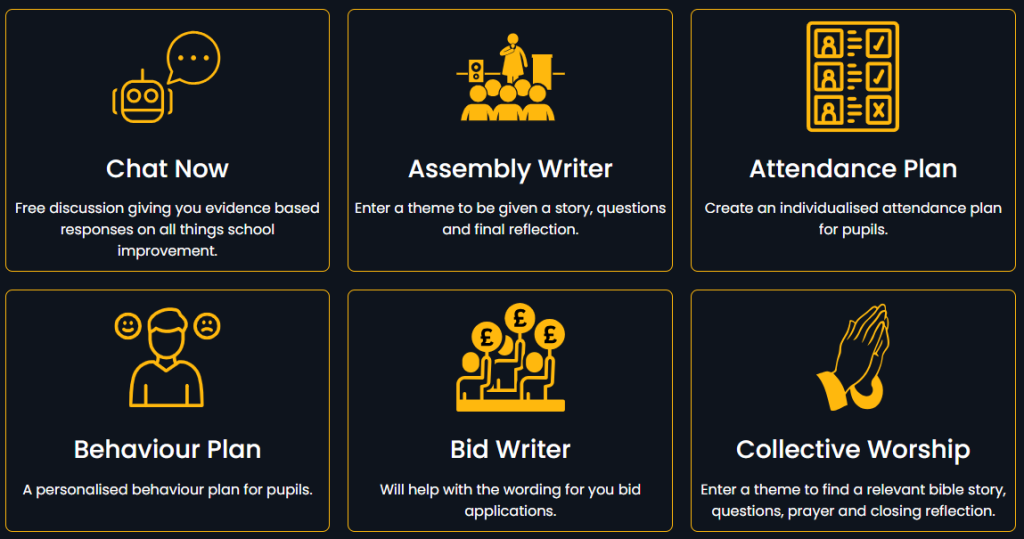

AI tools for school leaders

Former headteacher Craig McKee has created SLT AI to reduce the workload of senior leaders in schools. Unlike ChatGPT, this model has been trained on the latest information from the DfE, EEF and Ofsted. This means you should get an informed response based on the information it has been given. Some of the tools it offers include:

- Evidence-based responses on all things school improvement

- Personalised behaviour plans for pupils

- Bid writing applications

- Deep dive preparation

- Suggested points and wording for difficult conversations

- Help with interview questions and job adverts

Read more from founder Craig McKee below.

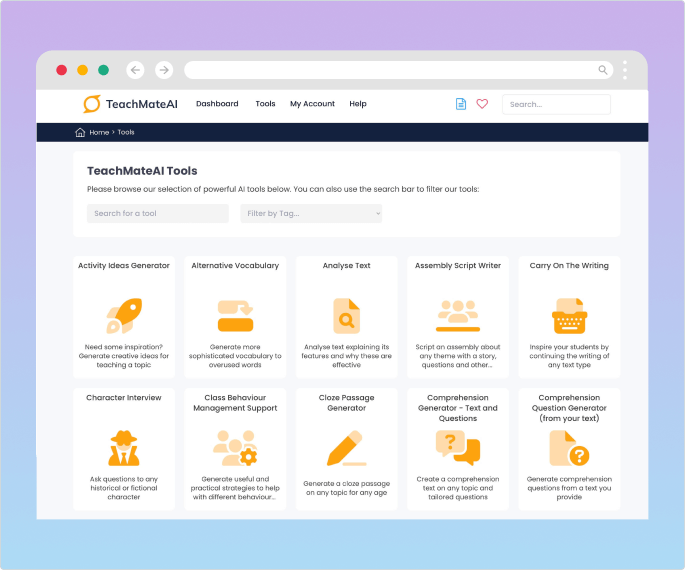

AI school report writers

Imagine if you could write all your school reports in a few hours, rather than the process dragging on for several weeks?

Tools such as TeachMateAI promise to help you do this. In fact, one primary teacher reported that the tool has reduced her report writing to “4-5 hours, maximum.”

This particular website, built by teaching and tech experts including Mr P, can also help you to:

- generate slideshows

- write comprehension and model texts

- generate maths word problems

- plan your lessons

Another website offering a similar service is Real Fast Reports. Here’s an example of how it transfers a set of brief bullet points into a report – meaning you can generate each one in just one to two minutes.

AI design tools from Canva

Canva, the online graphic design tool, has recently launched Classroom Magic, a suite of AI tools for the classroom. This includes Magic Write, which allows you to generate a first draft, reword complex content or summarise text.

Meanwhile, Magic Animate helps you to turn classroom materials into captivating videos and presentations in an instant. Magic Grab allows you to grab the text from, for example, a photo of a whiteboard or a paper-based resource, without having to rewrite it manually.

Magic Switch means you can reformat teaching materials instantly. So, for example, you can turn a presentation into a summary document or a whiteboard of ideas into a presentation.

Teacher’s prompt guide to ChatGPT

This Teacher’s Prompt Guide to ChatGPT will teach you how to effectively incorporate ChatGPT into your teaching practice and make the most of its capabilities. The guide covers generating prompts that will:

- Encourage students to think critically and solve problems

- Encourage students to think about their learning process and progress

- Help teachers improve their skills in using data effectively

- Produce open-ended questions that align with the learning intentions and success criteria of your unit of work

- Help you get to know students’ interests, strengths attitudes towards learning, and aspirations

- Analyse the effectiveness of different teaching strategies

Also check out this list of the best ChatGPT prompts for teachers.

AI teaching resources

Free programme for KS3/4

Experience AI is a free programme from Google DeepMind and the Raspberry Pi Foundation that gives you everything you need to introduce the concepts of artificial intelligence and machine learning to your KS3/4 classes. It contains lesson plans, slide decks, worksheets and videos.

KS3 science AI lesson plan

AI is already changing the way we live. Get your students exploring its impact with this free KS3 science lesson plan by Caitlin Brown. Students will explore how systems use machine learning, its impact on our lives, and the ethics surrounding it.

Example of teachers using AI in lessons

Create word banks

Create differentiated statements and definitions

Generate reading resources for a geography enquiry

Scaffold and model independent writing

Generate a Y4 writing lesson plan

Podcasts about AI in education

In this episode of The Edtech Podcast, Nina Huntemann and Lord Jim Knight attempt to understand how best to cut through the white noise surrounding AI’s hype, misinformation, exaggeration and marketing, and determine just how positive for education AI can be if done responsibly.

Dive into the hot topic of AI in education by listening to a podcast with a data and AI specialist who works at Google Cloud. The podcast covers:

- the convenience technology and AI can bring to the sector

- the importance of creating digital learning opportunities for young people

- how to give teachers the confidence to use technology in the classroom

- how to focus on the positives of technology

- safeguarding issues

- the ethical and legal issues surrounding new technologies

More useful resources

- DfE policy paper – Generative artificial intelligence (AI) in education

- The AI Educator Sunday newsletter

- A list of AI educator tools from The AI Educator

How to create a digital strategy that embraces generative AI

Al Kingsley, multi academy trust chair and group CEO of NetSupport, discusses the importance of adapting your strategy to take AI into consideration…

Generative AI has undoubtedly seen meteoric growth recently. Conversations in the education sector regarding the potential threats and opportunities have increased in tandem with these technological developments.

Although exciting potential opportunities beckon, concerns are also being – rightfully – raised by educators who feel overwhelmed by the growing use of this new technology.

Already in use

However, a more pragmatic view is needed. The reality is that schools have been making the most of the capabilities of non-generative AI for years.

Personalised learning tools and pathways that support student learning are a great example of this. So are management information systems tools used by leadership and administrative teams to analyse and understand issues such as attendance and attainment.

AI has therefore already been in use (albeit to varying degrees) in schools across the country, cutting teacher workload, informing decisions made by leaders and helping students to learn.

Taking this view, there is less need to feel daunted by the growing use of generative AI. This technology, in one form or another, has been present in schools for a while – and similar approaches can be taken.

The pillars of digital strategies will remain largely unchanged in the face of generative AI. However, adaptations will of course be needed.

Five key considerations for integrating new technological resources

- Having clarity on the educational purpose, intended use and purported benefits of any tool is critical, whether or not it’s AI-based. The adoption of technology is not a race. School leaders should not feel pressure to begin using any software simply for the sake of appearing ‘cutting edge’. Like all technology, some solutions will build up credible evidence of their efficacy over time. Others will be rightly discounted. Regular re-evaluation to measure tangible impacts will ensure the tool your school selects is the right one.

- Data protection and security should remain a priority; a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) will identify any potential risks.

- Is the tool programme-agnostic? How will it integrate with pre-existing systems and solutions already in use? This will be crucial in evaluating the potential long-term usage and benefits of new resources.

- Implement a clear, comprehensive usage policy for generative AI resources. Transparency should be a key element of this policy. Make it clear where AI is being used and what for – for instance, acknowledging the role of AI in the creation of any resources used by teachers.

- Supporting staff with thorough initial training and CPD opportunities, so they can confidently and efficiently use these tools. Without current and regular CPD, any technological resources risk becoming burdens; particularly in the current landscape of rapid innovation.

Students using AI

In addition to the above, it will be essential for educators to understand how their students are already using generative AI.

Recent research from the charity Internet Matters found that 54 per cent of children use generative AI tools for their schoolwork and homework. Despite this, 60 per cent of schools have not spoken to their students regarding the use of AI in this manner.

Remaining up-to-date with these trends can be tricky. However, edtech vendors and education community forums often share invaluable insights in this regard.

The advent of AI also reinforces the importance and value of the human-to-human dynamic in the learning journey.

The curriculum, and indeed our methods of teaching and assessment, will undoubtedly need to adapt in order to keep pace with the burgeoning AI era.

As AI continues to grow in capability, the balance in education is likely to shift further away from pure knowledge-building. It will move towards the impartment of relevant skills.

To keep pace with the integration of AI into many aspects of our every day, learners must be equipped with the ability to analyse and question the information in front of them, determining how to best utilise and apply knowledge.

Students’ ability to thrive in tomorrow’s world (and workforce) will depend on how educators can help their students in this regard.

Example ChatGPT command prompts to try

1. Lesson preparation and administration

You can create more time for yourself by enlisting the help of ChatGPT for tasks such as lesson plans, creating resources, marking work and analysing data.

Example prompt: Plan a 60 minute lesson on glaciation for a Year 7 mixed ability class

2. The generation of specific learning pathways

Counter the tendency towards ‘one size fits all’ teacher training by focusing your professional development on specific areas of need.

Example prompt: I am an ECT struggling with management of low-level behavioural issues. Can you suggest some strategies to move forward?

3. Streamlining research

Use ChatGPT to summarise articles before reading them, so that you can acquire better insights into whether or not they’re relevant to the field you’re researching.

Example prompt: Summarise Luckin, Rose (2020) ‘AI in education will help us understand how we think’

4. Helping you read more widely

ChatGPT can be used to recommend wider reading around a particular area of need, or just broad topics that you happen to be interested in.

Example prompt: Suggest key texts on AI in education

5. Critiquing your teaching

Another possible use for ChatGPT is to gauge the likely effectiveness of your lesson planning; you can then use its findings to help you better reflect on your practice.

Example prompt: I plan to do a group task with a mixed-ability Year 8 class. What might the limitations of this approach be?

Geoff Baker is a Professor of Education and Craig Lomas a Senior Lecturer in Education, both at the University of Bolton, and both former senior secondary school leaders.

Take a look at our other edtech posts on smart boards and management information systems. Visit the Bett Show to see real-life examples of educators using AI in the classroom.