Want Your Pupils to Listen? Try Speaking Less

Don’t become background noise, says John Coxhead

- by John Coxhead

Imagine being sat in a café, writing a postcard. Now consider the different sounds you might hear: a coffee machine, conversations, the clink of cutlery, a door opening and closing. How many of these sounds would you be actively aware of as you write?

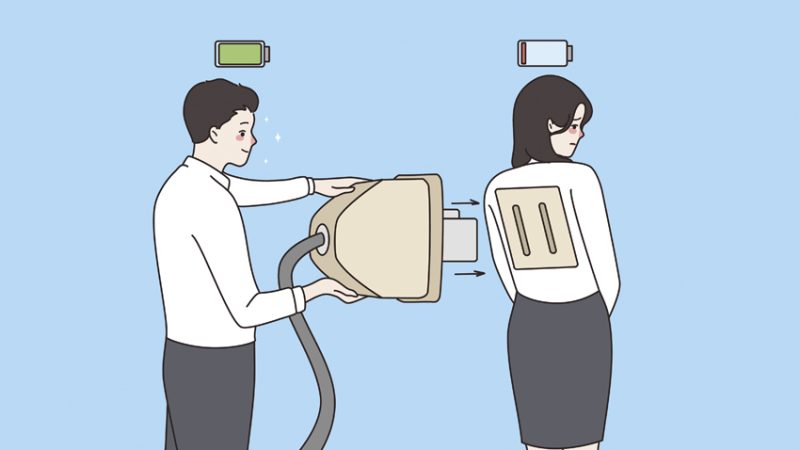

Over time, we tend to tune out and ignore ‘background sounds’ that we hear a lot. On a long journey, we soon become unaware of the hum of an engine. In an office, we become oblivious to the gentle tapping of keys on a keyboard. In contrast, sounds we hear less often grab our attention: the screech of breaks or an announcement on a train.

Now imagine being sat in a KS2 classroom, writing a story. As with the café, we could identify a set of ‘background sounds’ that we eventually become unaware of: the scratching of pens, footsteps, the shuffling of papers.

Likewise, other sounds would grab our attention: a loud sneeze, the bell, a knock at the door. The teacher’s voice, we would hope, would fall into the latter category. As the main tool for communicating knowledge and understanding to pupils, the teacher’s voice needs to be heard.

Children need to listen attentively to their teachers so that they learn more rapidly. If teachers talk too often, pupils are less likely to listen attentively.

Who would you pay more attention to: a teacher who talks a lot and typically fills periods of silence with repeated instructions or suggestions, or a teacher who is purposefully selective and succinct when they speak? Don’t let your voice become a background sound your pupils ignore.

Be succinct

I have become more aware of the importance of ‘succinct teacher talk’ by spending time in other teachers’ classrooms. In rooms where the teacher spoke a lot, I watched some children whose ears seemed numb to the teacher’s voice.

The insights I gained from this have made me take more conscious decisions about when, how often and for how long I speak to the whole class when I teach.

I took my ‘succinct teacher talk’ approach to the extreme during a Y6 transition afternoon.

Arriving at my door was a group of students with a reputation for poor classroom behaviour. I opened my door and looked at them. I smiled calmly and gestured for them to follow me into my room. One child at a time, I pointed to a chair. Two minutes later, they were all seated.

I pointed to the board. On display, were a set of instructions. After a moment of hesitation, they read the instructions and began the task in complete silence (using equipment that had been prepared for them). Throughout the next hour, I smiled but did not speak once. I occasionally wrote scores on the board (awarding points out of five for different competencies: common sense, work-ethic, quality of work, focus, etc). After 60 minutes each child had produced two pieces of work.

The class had been awarded good marks in every ‘competency’. They had proven to me that they had the potential for exceptional behaviour for learning. I certainly did not want them to work in silence every lesson and I told them so. I did, however, feel that they really listened when I spoke.

Would I do the same again at future transition days? Possibly not. It worked well for those children but it would not be appropriate for every class in every setting. It demonstrated, though, the importance of teachers using their voice selectively and appropriately.

Be selective

I have attempted various strategies when trying to minimise my own whole class ‘teacher talk’ and use my voice more effectively (see panel, right). Many of these are techniques that great teachers use daily.

However, when you start to make a conscious effort to talk as efficiently as possible, you may be surprised at your tendency to over-talk. A great exercise (if you can bring yourself to do it) is to make an audio recording of yourself teaching and listen back to it.

Reflect on your teacher talk. Did you need to say everything you said? How much was not relevant? How much was repetition? As an undergraduate, I trained as a screenwriter. Typically, we would redraft a scene seven or eight times.

The most common task when redrafting was to reduce dialogue. We had to be selective. Anything that did not need to be said, was axed. It was amazing how much meaning a character could communicate by saying very little.

The same, to some extent, applies to teaching. There are, however, two fundamental differences. The first is that your audience sits right in front of you – use this to your advantage by gauging their reaction. Have they understood? Are they listening? The second is that you only get to write one draft. Make it a good one! Be selective.

Make a conscious decision to use your voice wisely this year. I will end with an old Irish proverb: say but little and say it well.

How to minimise teacher talk

- Non-verbal cues save you from speaking unnecessarily. They can also save you from halting something you are part-way through saying (and, thus, having to later repeat yourself). They can also prevent you having to enter a verbal confrontation with a child in front of the whole class.

- Wait once you have asked for attention. The author, consultant and behaviour guru Bill Rogers calls this ‘tactical pausing’. Whether you ring a bell, raise your hand or say something, you need to wait for every child to respond. This means you can avoid shouting the same instruction three or four times; you say it once calmly when each child is listening. This reduces the amount you need to say.

- Consider the volume at which you speak. Loud teachers do tend to have loud classrooms. The teacher’s voice should be at a sensible level – this allows you to achieve emphasis, or grab attention, when you raise your voice.

- Give yourself time to think before saying something. Use ‘pockets’ of time (such as when pupils are opening their books) to consider what you need to say aloud to the whole class – it often isn’t a lot.

- On some occasions, you may choose to write instructions and display them. This can save the need to repeat verbal instructions.

- Use a timer. As well as being helpful for pupils, displaying a timer may help remind the teacher that a chunk of time is being allocated for independent work. Whole-class instruction and ‘teacher talk’ should be avoided in this time. Focus instead on whispering quietly to individuals as you support them.

Credit for some of these ideas goes to Bill Rogers – his work has really informed and developed my thinking.

John Coxhead is deputy head of Parbold Douglas CofE Academy in Lancashire. He is also a member of the DfE’s Teacher Reference Group. Follow him on Twitter at @johncoxhead89.