Secondary Maths

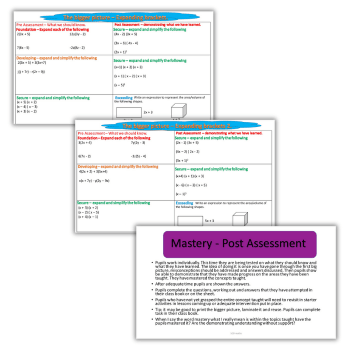

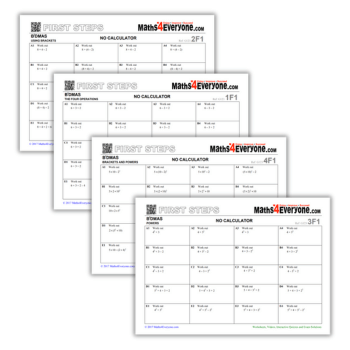

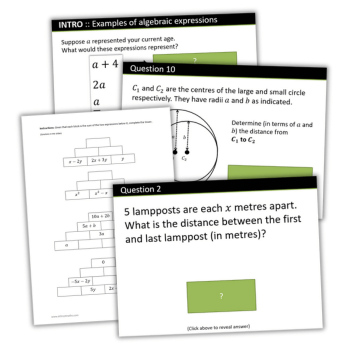

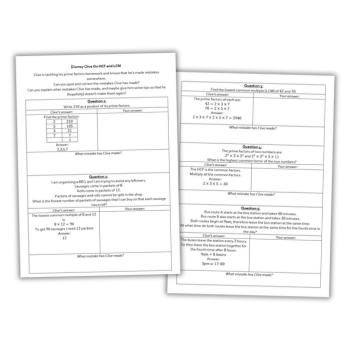

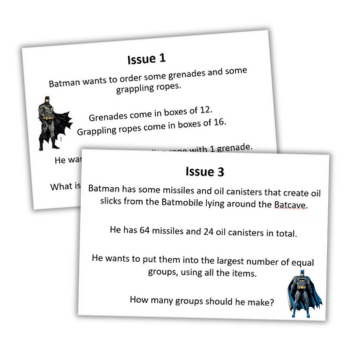

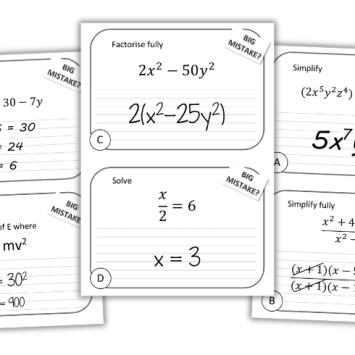

Are you looking for secondary resources to support you with KS3 and KS4 maths lessons? From maths games and lesson plans to worksheets and GCSE past papers, we have a range of engaging maths resources for your classroom, aligned to the maths national curriculum.

Explore Secondary Maths

Free Secondary Maths Resources

Secondary Maths CPD Downloads

Dr Colin Foster looks at specific areas of secondary maths that are often tricky to teach and shows how you can tackle them i... more

Maths anxiety, scotopic syndrome – we explore teaching methods to use (and avoid) to help pupils improve in maths

Add eight detailed KS3/4 maths lessons to your library that explore problem solving and effective teaching methods, all writt... more