RAAC – Lessons to learn from the school concrete crisis

The ‘concrete crisis’ has shown where the priorities of successive governments really lay. What lessons can we learn from the crisis?

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

What the concrete crisis tells us about politicians’ priorities

The ‘concrete crisis’ has shown where the priorities of successive governments really lay, says Carl Smith – and it’s not with young people or teachers…

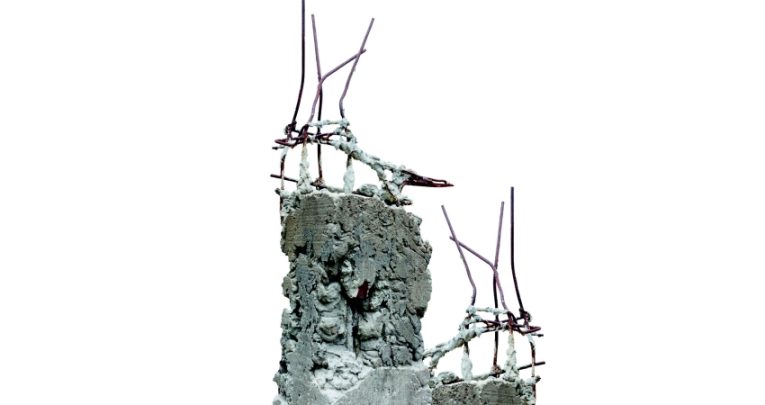

When presented with a challenging mix of post-war debt and a baby boom, how do you build lots of inexpensive public buildings, and particularly schools, quickly? Back then, RAAC (reinforced autoclave aerated concrete) was the answer.

RAAC shelf life

It was a wonder material whose time had come, and eager governments took full advantage. It was light, thermally efficient and easy to make. The perfect combination – albeit on the understanding that it had a short shelf life of around 40 years. If it were to remain in place any longer, it would be liable to collapse.

How suddenly wasn’t properly understood. But by the 1980s, it was fast becoming clear that we shouldn’t be using it in any buildings intended for long-term use.

The problem with public buildings, though, is that once they’re built and people start using them, they become very difficult and expensive to replace.

Five-year cycles

In our country’s democracy, politicians tend to work in five-year cycles. They typically don’t treat anything requiring a longer-term view as a priority.

Voters are generally reluctant to vote for parties intending to raise taxes. This is particularly true when the promised benefits will only become clear over 20 to 30 years.

So the buildings remain in place, and replacing them becomes someone else’s problem… except when they go wrong. And RAAC has gone very wrong indeed.

Schools built with RAAC in the 1950s are now 70 years old. Even those built in the 1970s are beyond their natural 40-year expected lifespans. The government has known about and understood the issue for years.

It’s one of the many reasons why the last Labour government embarked on its Building Schools for the Future (BSF) programme. Whatever the merits of that particular initiative, it at least meant that lots of schools were going to be rebuilt.

“The government has known about and understood the issue for years”

My own school had been scheduled for rebuilding in 2016. Like many, it was crumbling to the point where a full rebuild was going to be more cost effective than a patch-up. It was also very energy inefficient and expensive to heat.

None of that mattered to Michael Gove, though. The fact that it would have to be rebuilt sooner or later was neither here nor there; later was politically more convenient, so that was that. The government cancelled the BSF programme with nothing to replace it.

Act of vandalism

This act of vandalism now threatens the lives of thousands of children, young people and staff. In a sense, the present Education Secretary is simply unlucky to be around at the time when ‘Must do soon’ became ‘Must do immediately.’ However, we can’t as easily excuse the subsequent revelation that the government halved the budget for a proposed new school rebuilding programme in 2021.

The government has conveniently left the school estate to wrack and ruin for years. The responsibility for this lies with anyone in the past who ultimately decided to do nothing about it.

My school is now on the new rebuilding programme. It’s among a group the government has scheduled to ‘enter delivery’ from April 2025. That’s fully nine years after it would have been rebuilt under BSF.

In that time it has become horrifically expensive to heat and subject to frequent water leaks. In June a lightning strike ripped the roof off the entire main building. Fortunately, there doesn’t seem to be any RAAC, since most of the site was built pre-war, but that’s little comfort.

Different standards

RAAC can kill, as can asbestos. There are many problems with the school estate which, while not immediately life-threatening, would never be tolerated in the premises housing major companies. It would be bad for business.

Employees would refuse to work there. Yet when it comes to children and young people, different standards seem to apply. School leaders may protest, but there are other priorities and elections must be won.

Even now, at the time of writing, the apparent answer to the immediate problem is to kick other problems even further down the road. Taking money out of the existing capital budget for schools, rather than putting new money into the system, simply means that all those other desperately needed improvements to school buildings will be delayed yet further.

“When it comes to children and young people, different standards seem to apply”

It seems that when it comes to school building, the lessons are never learned.

Carl Smith (@SmithCarl19530) is the principal of Casterton College, Rutland, has written on a range of educational topics and is a regular contributor to ASCL’s Leader magazine

The project management lessons to be learnt from the RAAC crisis

Dr Serkan Ceylan explains how the RAAC crisis has highlighted the need for better understanding and training in effective project management…

Each year, the nation wastes enormous sums of money on failed projects. One recent report estimates the actual figure as being around £120 billion annually – largely due to mismanagement.

Trending

Yet poor project management doesn’t just waste money. In the worst cases, it can be detrimental in many other areas, such as public health and safety.

This recently came to light with the RAAC crisis. This forced school students into temporary structures after investigators found a number of older school buildings had structural weaknesses stemming from the use of reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete installed decades prior.

But how did we allow the situation to get to this point? When it comes to big construction projects, you might think that those in charge would have taken all the relevant precautions and measures to prevent such disasters from happening – but that plainly didn’t happen here. So let’s unravel what did happen.

Big projects, common issues

The RAAC crisis emerged out of two key problems, the first being miscommunication. When the government first raised issues relating to the presence of RAAC in school buildings, it tasked individual schools with identifying the presence of the material on their premises. This was despite most likely possessing neither the knowledge nor the resources to do so.

“How did we allow the situation to get to this point?”

This points towards a distinct lack of communication between what was needed, and ended up being actually done.

The second problem involved poor time management, in that resolving the issue took far longer than expected. When issues arising in ongoing projects are first raised, the relevant teams should be agile, responsive and flexible in a way that enables them to respond to any number of issues and hopefully overcome them.

When applied to the RAAC situation, we can see how the issue was initially raised in the 1990s, but that it took some time for any action to finally be taken.

We can assume that perhaps the consequences weren’t made clear enough during this period. However, after a portion of the staff room ceiling collapsed at Singlewell Primary School in Gravesend in 2018, quick action was needed.

We’ve often seen how a combination of poor communication and ineffective task allocation can derail effective project management. But there are some ways of streamlining the planning process to prevent these kinds of issues from presenting legislative roadblocks. This is where a common method called Agile project management can help.

Causes of collapse

Effective project management practices will be contingent upon robust planning, risk management, stakeholder engagement and clear communication. Many project managers are beginning to adopt the Agile method as it can provide a better structure, which in turn can help to mitigate some of the common issues encountered in large projects.

“Many project managers are beginning to adopt the Agile method as it can provide a better structure”

Agile management is an iterative approach to delivering a project throughout its life cycle that involves transparency, regular reviews and continuous improvement. Its main principles include:

- Embracing changing environments

- Breaking tasks into smaller pieces and prioritising them in terms of importance

- Promoting collaborative working by engaging all stakeholders

- Learning and adjusting at regular intervals to ensure positive outcomes

- Integrating planning with execution, to encourage self-organising mindsets that can help teams respond to changing requirements

Agile management

Applied to the context of the RAAC issue, Agile management would have allowed for a quicker, more flexible approach. For example, many headteachers have stated they were unable to properly assess RAAC in their school buildings. That’s because, rather than undertaking a large-scale survey of the entire school estate, ministers instead relied on school leaders to respond to questionnaires that they originally sent out in 2022.

A good solution in this instance might have entailed regular, clear and structured meetings for the purpose of reviewing progress. Questions asked at such reviews could have included:

- What did we do yesterday that helped the team?

- What do I need to do today to help move things forward?

- Are there any blockers that will prevent our team from moving forward?

These questions might have drawn attention to the issue far sooner – especially if the DfE came to the conclusion that its initial approach wasn’t working well for headteachers and school leaders. That may have prompted a series of changes and different decisions – such as enlisting teams of professional surveyors, dispatching them to schools and having them lead the assessments themselves.

Project management for school leaders

For projects to be successful – be they internal initiatives developed within your school, or prompted by collaborations with external parties – the goals you need to work towards include cultural change and leadership buy-in. This is alongside a willingness to adapt existing processes and structures to better align with Agile principles.

“These questions might have drawn attention to the issue far sooner”

With the success of many school-based projects being dependent on multiple partners, it’s not uncommon to encounter difficult challenges with inter-organisational coordination.

We can put many of the unresolved tensions we’ve come across in the course of our research down to:

- cost-value concerns

- project approval

- matters of policy and governance

- issues with culture

Steps to implement

School leaders can overcome such challenges by implementing the following steps:

- Training staff in creating a shared understanding of how Agile will alter the way you handle big changes within your school

- Holding regular meetings and catch-ups that follow a clear agenda, to ensure you’re keeping things on track. Remember, communication is key – prioritise your interactions with individuals over the broader process

- When sourcing external contracting, it should be with suppliers that fit with Agile models

- Be prepared for change, and plan for it by reviewing and developing your organisation’s structures, hierarchy and HR systems; try to respond proactively to change, rather than sticking to a set plan

For Agile transformation, you still need a great deal of organisational design effort. To tackle this, school leaders need to work towards: people over processes, a better understanding of Agile, leadership buy-in and embracing change.

Dr Serkan Ceylan is Associate Dean of the Faculty of Business at Arden University, as well as a full-time senior lecturer in project management, an accredited project management trainer and a Fellow of both the Higher Education Academy and Association for Project Management

His book, AgileFrame®: Understanding Multifaceted Project Approaches for Successful Project Management is available now (International Project Management Consortium Ltd., £35)