Rob Biddulph – Why the arts are just as important as STEM

The award-winning author on why the arts are essential for a well-rounded education, and the positive impact of cross-subject projects

- by Rob Biddulph

Eighteen months ago, I broke a Guinness World Record for the largest ever online art class when over 45,000 people simultaneously drew a whale with me.

The Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, awarded me a Point of Light award, saying “you inspired the creative spirit of the nation with millions of families tuning in to your #DrawWithRob series and spending special time together honing their artistic skills. So on behalf of the whole country, I am delighted to recognise your service to others.”

This is the same government that is cutting funding for arts courses in the UK by 50% across higher education institutions.1 And it’s the same government that backed an ad campaign suggesting that dancers should retrain to work in cyber.

I’m sure I’m not the only one to notice the discrepancy between their rhetoric and their actions.

Disclaimer: I’m not an expert on education. Far from it. But I have put three daughters through the state system (two of them are still in it). In our experience, particularly with our eldest daughter, there was an unspoken yet quietly insistent suggestion that all paths should lead to that holiest of grails, an academic degree at a Russell Group university.

To be clear, I am not blaming teachers in any way. As far as I’m concerned it’s an entirely legislative issue. Nevertheless, it can be incredibly demotivating for students, like my daughters, with a more artistic bent.

At various points, my girls have been made to feel like they are also-rans in their own school which, unsurprisingly, gets my goat.

Reduced arts funding

My poor old goat. It’s always getting got. And the chipping away at arts funding in schools is one of the chief culprits. In February 2021, the Gov.uk website said: “The upshot (in the increase in STEM subjects being studied) has been a steady decline in the number of hours and staff dedicated to teaching arts subjects in schools (DfE, 2019) and a reduction in the number of young people opting for arts subjects at GCSE and beyond (CLA, 2019).”

What a tragedy. There are so many children who arrive at school with a genuine talent in an artistic discipline, and they are crying out for someone to light a fire beneath it. But instead, that spark gets doused.

The talent is dismissed, and the children are surreptitiously steered in another direction before it has a chance to flourish. It’s infuriating.

Not everyone is cut out to be a STEM person and operate in an analytical, academic environment. In fact, I think that putting all of our eggs into the STEM basket is an extraordinarily short-sighted thing to do, particularly in this age of automation.

Surely, it’s the creative jobs that are the least vulnerable to the relentless march of AI. After all, you can’t get a robot to dance the perfect Argentine Tango or paint Guernica.

The kernel at the heart of the whole STEM vs The Arts problem is, I believe, people’s inclination to separate the two. For some reason, we have started to believe the notion that science and art are mutually exclusive, which, of course, they’re not.

In fact, they’re mutually dependent. In order for them to be fully functional they need to operate together and support one another.

Science and creativity

In 1878, the first-ever winner of the Nobel prize in Chemistry, Jacobus Henricus Van ’t Hoff, put forward the idea that scientific imagination correlates with creativity outside of science. ‘Anyone can make rote observations,’ he said, ‘but it takes leaps of imagination to come up with hypotheses and the experiments to test them.’

Indeed, many of the best-known scientists throughout history had artistic inclinations. Newton was a painter, Galileo was a poet, and, according to one study, nearly all Nobel laureates in the sciences practice some form of art as adults.3

Leonardo da Vinci, a man who was pretty decent with a paintbrush but also knew a thing or two about engineering, agrees. He advised us to “Study the science of art. Study the art of science”.

Another rather bright chap, Albert Einstein, also chips in. “The greatest scientists are always artists as well”. When big brains like theirs seem so certain about it, I for one think we should listen.

The fact that this kind of historical precedent exists gives me hope that, in the future, we might include art in STEM – making it STEAM. Hopefully this movement, which has already gained some traction, will come to fruition sooner rather than later.

It’s certainly been a long time coming. Whichever way you cut it, the fusion between art and science is a very real thing, and I believe that the government has a responsibility to impart that information to our kids via the education system.

So many career paths involve a combination of logical and creative skills: architects, product designers, marketers, software developers, advertisers, therapists, researchers, you name it – a combination of STEM and arts can only benefit, or even be integral to, a multitude of career options.

Cross-subject teaching

In practice, schools employing cross-subject projects are already seeing amazing results, including an increase in attendance and higher grades across the board.

Bridgemary School in Hampshire, for example, has now employed a Director of STEAM, and as a result they have noticed an upshot of loans from the library and a decrease in behavioural referrals.4

Dame Nancy Rothwell, chair of the Russell Group of universities, speaking at the Times Higher Education University Impact Forum in 2021 said: ‘I had a fascinating conversation with someone who runs a big gaming company. He asked about our graduates. I said: ‘Presumably, you want our computer science graduates.’ He said: ‘No, I want your experts in drama, creative writing, history, global cultures – creative people. We can do all the rest.’ I wish my eldest daughter’s school had known this.

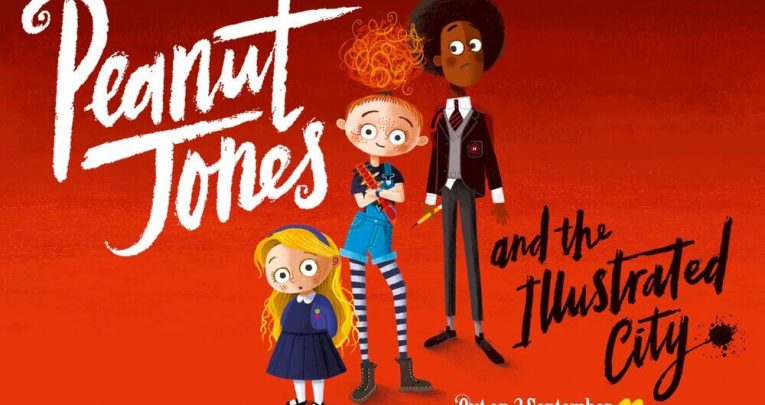

Look, this argument is not new, but it’s one that I hope can inspire the government in the years to come. And it was one of the motivators that inspired me to write my debut fiction novel, Peanut Jones and the Illustrated City, in which the artistic protagonist is forced into a STEM-focused school by her accountant mother.

One of Peanut’s companions, Rockwell, has strengths that lie in these logic-based subjects, though the underlying theme of the story is, as you can probably guess, that it’s their combined knowledge and passion for these disciplines that is required to solve problems.

It takes the two of them working in tandem to realise that one doesn’t function particularly well without the other.

All this being said, the truth is that I didn’t set out for my book to be a polemic about the government’s defunding of the arts. But if, through this story, I can wave a flag to let people know that they matter, that they’re as important as the STEM subjects, and that they’re here to stay, then I’ll happily do that.

I do have hope that the careers officers of the future will feel able to advise their charges to follow their hearts and nurture their talents, whatever they may be. And, as I say in my book, once you choose hope, everything is possible.

Rob’s latest book, Peanut Jones and the Illustrated City (£12.99 HB, Macmillan Children’s Books), is out now. Follow Rob on Twitter @RobBiddulph.