Rhythm and Rhyme can Keep the Pleasure of Reading and Writing Alive for Every Child

The music of words forms the building blocks for much of the language around us

When I think about poetry, music is never far from my mind. It’s the sounds of words – their hum and buzz, the way they chime and bounce together – that give poetry its bite and poise. And at the heart of poetry’s power to make music from words, sit rhythm and rhyme.

The amazing capacity of nursery rhymes to introduce language to the very youngest children is no secret: it is through these singsong rhymes that we ready our ears for words, drawn along by the tick and ring of rhythmic, rhyming verse.

The challenge, perhaps, is to keep that connection between language and music vivid and alive in the classroom as children grow older.

So, with the help of Charlotte Hacking at the Centre for Literacy for Primary Education, here are some ideas on how rhythm and rhyme can bring literacy to life right across the primary years.

At the centre of what make rhythm and rhyme so appealing and important is the play of sound. I always urge young readers to speak texts aloud wherever possible and to roll each syllable around the mouth.

With younger groups, playful texts like tongue twisters and nonsense verse are brilliant ways of engaging directly with the musicality of language, while also welcoming a spot of (manageable) mischief into the classroom.

Moving one’s body to poetry can be a fun way of bringing language’s rhythm to life: have a go at marching or dancing together as a poem is read aloud.

Meanwhile, Dr Seuss’ books for younger children remain firm favorites because they place sense in the service of sound, usually through rascally rhymes. As such, these poems are a brilliant springboard for freeing up the imagination and spurring children on to try their hand at some simple rhyming of their own.

As children grow, keeping this connection between written language and sound can sometimes become more difficult, not least as reading tends to become more solitary.

Finding playful ways to turn the written word into a performance is one way to refresh children’s enthusiasm and curiosity about language.

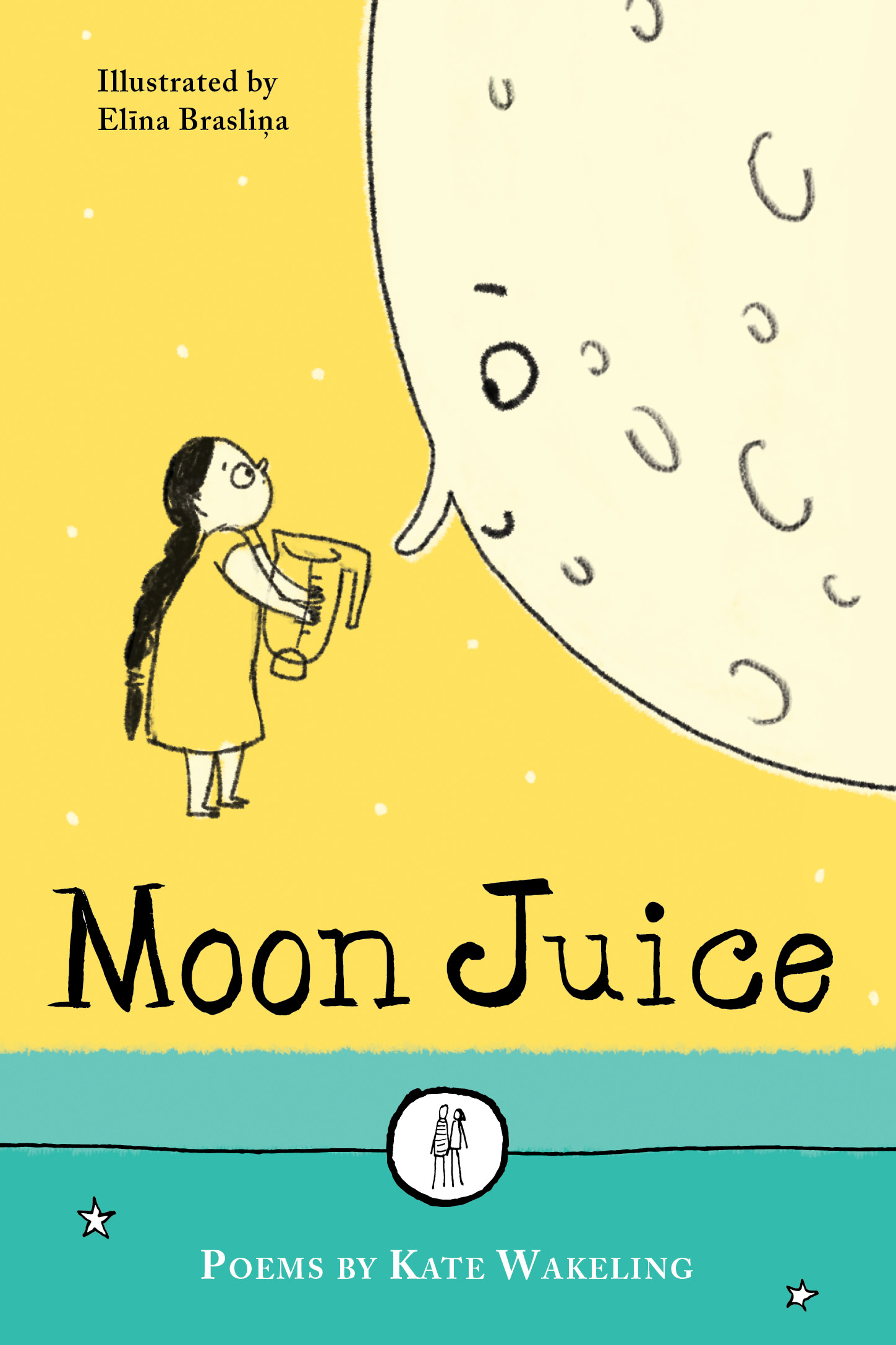

I’ve been amazed at the response from KS2 groups to my poem Comet from my book Moon Juice.

I wanted to enact something of the pace and thrill of a comet through the poem’s form, and enjoyed getting the rhythm and rhyme as crisp as could be, filling each line with tongue-twisting details so that when read at pace, the poem would sound like a fierce burst of energy.

The poem also comes with an instruction to the reader that it should be read as quickly as possible and in as few breaths as can be managed, with the aim that readers might be enticed into performing it aloud too.

I loved adding something of a physical game into a poem’s set-up on the page and have been delighted by how much fun it seems to have generated for readers.

Comet contains a few tricky bits of vocabulary but the urge to take part in the poem’s performative challenge seems to help children sail through these issues – or even better, to want to solve them for themselves.

Here’s a video of me reading the poem. See if anyone in your class can beat my time. (I bet they can.)

Some particularly appealing forms of language for older children – spoken word poetry, song lyrics and rap – draw heavily on taut rhythmic structures and rhyme schemes, and can be a brilliant way of reinvigorating their enthusiasm for literature. Finding diverse, engaging performances to share is key.

CLPE’s Poetryline offers a fantastic range of poets reading and talking about their work in lively, accessible ways.

As a starting point, I particularly recommend the pulse-ticking verse of Jamaica-born poet Valerie Bloom, a tremendously expressive and charismatic writer and performer whose poems remind us just how intensely language can shimmer and sting.

When young people are writing their own poetry, it’s worth noting that sometimes rhythm and rhyme can be an encumbrance. While many children derive great satisfaction from spinning verse that ticks neatly along in its rhythm and rhyme, sometimes a poem’s subject matter demands a different form and the imagination needs to roam.

That said, it’s equally important to bear in mind that ‘free verse’ needn’t by definition jettison rhythm and rhyme. Indeed, in my own writing, free verse is where rhythm and rhyme feel most alive to me.

I’m always seeking to encourage young readers to explore the subtleties of rhythm and rhyme in poems, even when it may seem at first glance (or hearing) to be absent.

Invite children to find the pulse in a line of seemingly ‘unmetered’ poetry by walking along to the text while it’s read aloud – or together track down all the internal half-rhymes twinkling within a poem, even if these rhymes are not stacked up at each line’s end.

Note too that a certain kind of rhythm in a free-verse poem can be created by the white space on the page.

In my poem My Ghost Sister I wanted to create a feeling of loneliness and floating otherworldliness, so set its lines drifting across the page, conjuring (I hope) a sense of space and silence.

Being alive to the rhythm of language beyond a straightforward pulse is crucial both to writing and reading poetry, and resources like the verse novels of Sarah Crossan are a wonderful example of the craft of free verse.

Rhythm and rhyme are the building blocks for much of the language around us. From the first nursery rhymes we hear to the vigour of a football chant, rhythm and rhyme are so often what prompts language to move us.

And by encouraging young people always to keep their ears open to the music of words, we can help keep alive the power and the pleasure of reading and writing for every child.

Kate Wakeling is the author of Moon Juice (£8.50, The Emma Press) and 2017 winner of the CLiPPA, the only award for published children’s poetry.

Kate Wakeling is the author of Moon Juice (£8.50, The Emma Press) and 2017 winner of the CLiPPA, the only award for published children’s poetry.

The CLiPPA and the free schools shadowing scheme that accompanies it are run by Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE). Find free poetry teaching resources at its website.

Find Kate at katewakeling.co.uk and follow her on Twitter at @wakelingkate.