Why we need a better post-maternity process for teachers

New mothers can have a difficult time confronting the assumptions and expectations of colleagues upon returning to work – but it doesn’t have to be that way, writes Nikki Cunningham-Smith…

“Oh, hey – I didn’t know you’d be back so soon. How was your break? Must have been nice! Wish I could have nine months off to chill…”

Those were his final words. I’m currently awaiting trial, but that’s another story for another day…

I’m joking, of course. I’d never admit to committing such a heinous crime in print. Would I do it? Well… I’m not so sure. Because that seemingly casual statement was the very first thing that someone said to me in an external agencies meeting upon my return to work.

There was so much to unpack in those words. It took less than 30 seconds for one simple statement to make me feel that the time I’d spent away was going to do serious damage to my much-loved career.

Like a gunshot

In case you haven’t already guessed, the throwaway comment described above was directed at me after returning to work following a period of maternity leave. And every part of it fired into my chest like a gunshot.

“I didn’t know you’d be back so soon…” Why aren’t you at home with your baby? BANG.

“How was your break?” You’ve clearly spent this time off having a jolly… BANG.

“Must be nice…” Nothing remotely negative could have possibly happened to you whilst you were at home, enjoying all those cake and coffee mornings. BANG.

“Wish I could have nine months off to chill.” How lucky are you to have had a holiday; not like me, working hard to the bitter end. BANG.

Now, of course, those sentiments likely weren’t what this individual intended to convey. I’m sure that what he said was genuinely meant as an attempt to catch up with me and see how my absence had been – but that’s certainly not how it felt.

Despite being in a world where we’ve finally accepted the idea of allowing women to return to their pre-birth physical shape naturally, rather than ‘snap back’ at speed, we’re still no closer to confronting expectations that we should ‘snap back’ mentally.

When I re-entered the workplace, I was very aware that I wasn’t the same leader that had left. Had I been absent from work due to sickness, I’d have likely had at least one return-to-work meeting so that steps could be put in place for a phased return. This is typically done to help long-term absent individuals acclimatise, and not feel overwhelmed on their return – because if they are, it could result in them needing to take yet more time away.

This kind of phased post-maternity process may well happen in some schools, but I’d say it’s far from being embedded best practice. Who checks up on these members of staff in the weeks, months, maybe even years following their return from maternity leave? Would their mental wellbeing be better supported if they knew they didn’t have to go looking for help, but that it would there waiting for them?

Relentless strain

Some of you might have heard the phrase, ‘We expect mothers to work like they don’t have children, and raise children like they don’t have work.’ Is it any wonder that the resulting strain can be so hard and relentless? If left unchecked, these feelings could pave the way for further stress, post-partum depression and even trigger delayed post-partum psychosis.

The support new mothers receive upon returning to work is often dependent on specific settings, rather than any formal legislation or even solid guidance. Everything is left open to interpretation, with the result that things can sometimes get lost in translation.

Having said that, employers can feel a certain amount of caution when it comes to putting support in place for returners, since contacting them during maternity leave could be seen as exerting undue pressure.

Beyond that, adopting a maternity policy that closely resembles that used for long-term sickness may imply that the person returning is weaker than they were previously, which isn’t the case. In fact, some women will be raring to go, having spent much of their leave thinking of ways to revive their brain cells after all those nursery rhymes.

Just the thought of having an adult conversation, enjoying a hot beverage and re-engaging with the profession they love will be more than enough to spur them on.

No one left behind

So what can be done for these returners to ensure no one is left behind? First, agree on a process prior to the maternity leave commencing. What will contact with school look like in terms of frequency and the main point of contact?

This person doesn’t necessarily need to be a line manager – just someone able to keep the lines of communication open (assuming the recipient wishes to be contacted) in an informal, yet informative manner. Training opportunities, job vacancies and staff parties can all remain on the table, without the person on leave having to trawl through endless emails in order to keep up with what’s going on.

Second, provide ‘Keep in Touch day’ options. I’ve seen stressful situations inadvertently develop when a mother has felt unsure whether their request for such days will be accepted, or that their return to work for a day wasn’t successful enough to warrant the temporary childcare arrangements.

If a mother believes they’re simply being used for cover, or that there’s been no meaningful planning around their return, there’s a good chance that they’ll feel less useful and more distant from their colleagues as a result – thus adding to the anxieties around their abilities.

Clarifying the individual’s expectations prior to them going on maternity leave will allow more time for discussions, as well as any necessary adjustments and replanning whilst they’re still in work ahead of baby’s arrival.

Transparent scenarios

Times are changing, with more opportunities available around shared parental leave and flexible work options. Staff are becoming savvier about what they’re entitled to. Gone are the days of endless October and November babies, so that the six-week summer holiday can be factored in to maternity pay.

It remains important, however, that schools are upfront with what they can and can’t provide. Removing the need for parents to do research on the school’s behalf will enable them to focus on the immediate task at hand – namely growing and looking after a new baby.

I don’t believe that some of the attitudes I’ve encountered towards maternity come from a place of malice, but rather from a place of ignorance – possibly indicative of dated attitudes from those who have never experienced labour or witnessed their partner undergo it.

Introducing CPD sessions around having such conversations can form the basis of more structured returns and fairer discussions. Exploring open and transparent scenarios will help tackle misinformation and give everyone greater confidence in talking to, and being supportive of new mothers.

Update your risk assessment to account for this period of return. Treating that initial period after pregnancy with the same level of importance as the period immediately before will enable mothers to freely converse with their schools, without needing to fear any discussions that might be damaging to their current status within school.

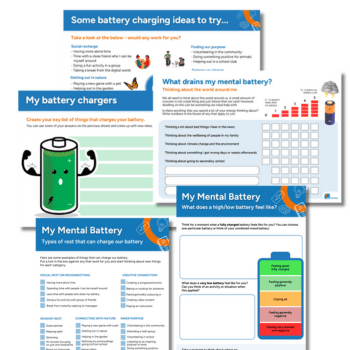

Finally, make mental health support part of your standard offering. The ability to provide, or signpost to external, support will be gratefully received. The recipient may not know at what point they’ll need it (assuming they ever do), but it’s still nice to know that it’s there.

Oh, and when your colleagues return, ask them how their morning was. Many parents will have already worked an intense shift before they’ve even set foot on school premises!

Nikki Cunningham-Smith is an assistant headteacher based in Gloucestershire