Mental health in schools – ‘Brave’ boys but ‘dramatic’ girls?

We should celebrate boys’ willingness to turn to others for mental health support, but let’s not compare their ‘bravery’ with girls’ ‘attention-seeking’

Traditional wisdom states that there’s a clear and universal gender divide when it comes to experiences of mental ill health.

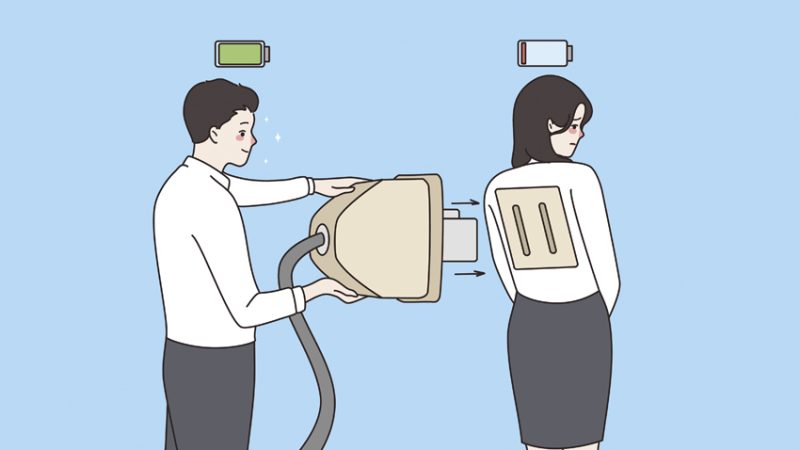

Where women and girls find it relatively easy to discuss their psychology and emotions, for men and boys stigma often renders them silent.

People often use statistics around suicide as evidence for this viewpoint. Men are up to three times more likely to end their own lives than women.

There is, of course, some truth in this. Yet it doesn’t tell the whole story, and it certainly doesn’t always apply in the context of young people.

Mental health in schools

The perceived ‘rules’ around masculinity prohibit the showing of vulnerability. Many men see a reductive interpretation of stoicism – never asking for help, never discussing problems – as being synonymous with ‘strength’. Yet increasingly, boys and young men are challenging the social rulebook.

Despite the terrifying popularity of influencers like Andrew Tate, who seem intent on returning to an era of restrictive gender stereotyping, young men often tell me they don’t feel any shame in opening up to their peers about their mental health, and would be sympathetic and discreet if approached by others for their advice.

Many teenage boys in my school focus groups say they feel frustrated by the perception that ‘men don’t talk about their feelings’.

From their perspective, they are talking – just not necessarily in the same way, or in the same environments as their female peers.

They’re less likely to book an appointment with the school councillor. But they’ll happily open up to a favourite teacher, sports coach or other mentor.

Generational bias

These observations are in line with research findings by the suicide prevention charity CALM. It found that women typically seek out mental health expertise more often than men.

As such, the charity has found it more advantageous to provide mental health training to those individuals who men are confiding in already.

The notion that men only ever talk about football and cars is, I believe, a stereotype based on the behaviour of older generations.

This may also explain the responses young people can receive when disclosing mental health struggles. Boys are often lauded as being ‘brave’ for doing so. And yes, while it’s courageous for anyone to show vulnerability publicly, adults will typically apply the context of their own age cohort and assume it’s still more difficult for boys than girls.

Conversely, girls will often receive the verbal equivalent of an eyeroll. A YouGov survey commissioned by CALM and conducted in summer 2023 found that one in five girls and young women seeking help for their mental health had been told they were being ‘dramatic’.

A third meanwhile said someone asked them if they were ‘overthinking things’. 20% were asked if they were ‘on their period’. Unsurprisingly, the survey also found that 22% of participants feared people seeing them as ‘attention-seeking’.

“Girls will often receive the verbal equivalent of an eyeroll”

What doesn’t help

So, what can school staff do? The simple, yet powerful fact is that we each have the power to recognise and challenge our own inherent biases. The National Institute for Health & Care Research surveyed young women for their thoughts on what they considered to be the least helpful responses to their health disclosures by trusted professionals. Those surveyed highlighted the following:

- Seeing mental illnesses with a strong behavioural element – such as eating disorders and self-harm – as ‘self-inflicted’, with recovery merely a question of addressing physical symptoms (e.g. patching up wounds or gaining weight)

- Assuming that Black women and girls are inherently ‘strong’. Therefore they have the capacity to cope with more adversity than their peers of other races and genders

- Not being explicit about confidentiality, and therefore destroying trust.

For educators, that last point means being upfront with students from the start as to what would constitute a safeguarding issue the teacher would have to share. This is at the same time as reassuring them that they will otherwise be as discrete as possible.

Above all, we should ask ourselves what our own responses would be if we heard similar sentiments expressed by a man or boy.

Natasha Devon is a writer, broadcaster and campaigner on issues relating to education and mental health in schools; to find out more, visit natashadevon.com or follow @_NatashaDevon. The Samaritans operates a 24/7 advice and support service. Contact them via phone on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org.