CLPE – Poetry teaching advice from the experts

Not sure how to approach poetry in the classroom? Literacy experts and CLiPPA-winning poets are here to help…

- by Teachwire

Poetry – what works in the classroom

In January 2023, the CLPE and Macmillan Children’s Books (MCB) came together in a new partnership to learn about poetry in primary schools. This began with a survey aimed at primary teachers, to gain a picture of poetry practice and provision.

80 per cent of teachers told us that they thought poetry was a significant part of a literacy curriculum. As positive as this sounds, though, it still means that one in five of the schools did not see poetry as significant in their curriculum.

Teachers reported that children really enjoy hearing, writing and performing poetry. However, they also told us that in 93 per cent of schools, teachers read poetry aloud less than once a week. In nearly 20 per cent of the schools, children never have the opportunity to hear a poem read aloud.

The survey results also showed that schools have limited poetry book stock. In 79 per cent of classrooms, book corners contained fewer than ten poetry books. In 44 per cent of classrooms, the figure was five or lower.

This is drastically low if we want to create an environment where children can see a range of poetry that gives them a broad perspective of what poetry is, what it can be and who writes it. It also limits poetry as a free choice for independent reading or reading for pleasure.

“We don’t have a large collection at school to choose from. There isn’t a budget for me to buy several books for the class.”

Limited progress

Previous research (Teachers as Readers, Cremin, et al., 2007; Poetry in Schools, Ofsted, 2007) showed that primary phase teachers have a limited knowledge of poets. Responses from our survey showed that this has not moved on in the 16 years since these original reports.

Aside from Joseph Coelho (who has come to prominence in his role as Waterstones Children’s Laureate 2022–2024), Valerie Bloom and Julia Donaldson, the names of the top nine poets listed by respondents matched those in the Teachers as Readers survey from 2006–2007.

“I love teaching poetry but feel less confident selecting poems. My knowledge of poets is not very diverse. I would like to improve this to influence other members of staff.”

What’s in the way?

We also learned that there are many perceived barriers to the regular teaching of poetry. The most commonly cited were:

- Lack of time, confidence, knowledge and/or training

- Lack of access to poets, poems and poetry texts

- Finding it difficult to see the grammar and writing expectations in poetry activities

- SLT and/or other teachers not valuing the importance of poetry

- Poetry not being prominent enough in the national curriculum or assessments (SATs)

- National or school curriculum weighted to fiction and non-fiction

- A need to prioritise assessment preparation

Addressing the issues

Following the survey, we embarked on ‘The Big Amazing Poetry Project’. This was a training programme for 30 schools that completed the survey. It specifically addressed some of the issues brought to light and demonstrated the value of poetry in the primary curriculum.

We developed and led the project in partnership with two leading children’s poets, Valerie Bloom and Matt Goodfellow. The schools involved received a free poetry library from Macmillan to support them in creating physical and joyful spaces for poetry.

On each day, we introduced poets, poems, teaching approaches and ideas that teachers could easily take back and replicate in their classrooms. We gave them texts and resources to facilitate them in using and applying what they had learned.

One of the most instantaneous and effective ideas was simply exposing children to poetry regularly. We introduced teachers to a wide range of poetry using an approach called poetry papering.

This involves pinning up poems by different poets around the learning space. This exposes teachers as well as children to poems and poets they had not met before. This approach gives more choice and voice in selecting poems of personal significance. Discussing these poems allowed a greater depth of response, understanding and empathy.

Bringing out the books

The teachers were given a copy of Macmillan’s Big Amazing Poetry Book and introduced to CLPE’s bank of poetry videos. This had immediate impact on children’s engagement and enthusiasm for the work of particular poets.

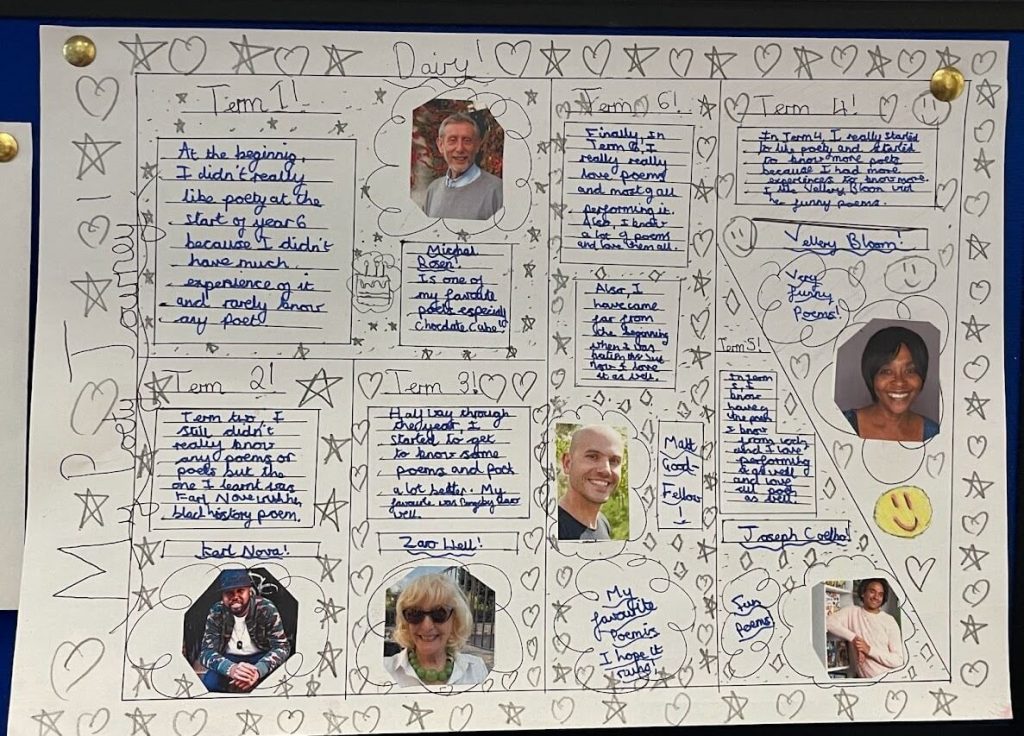

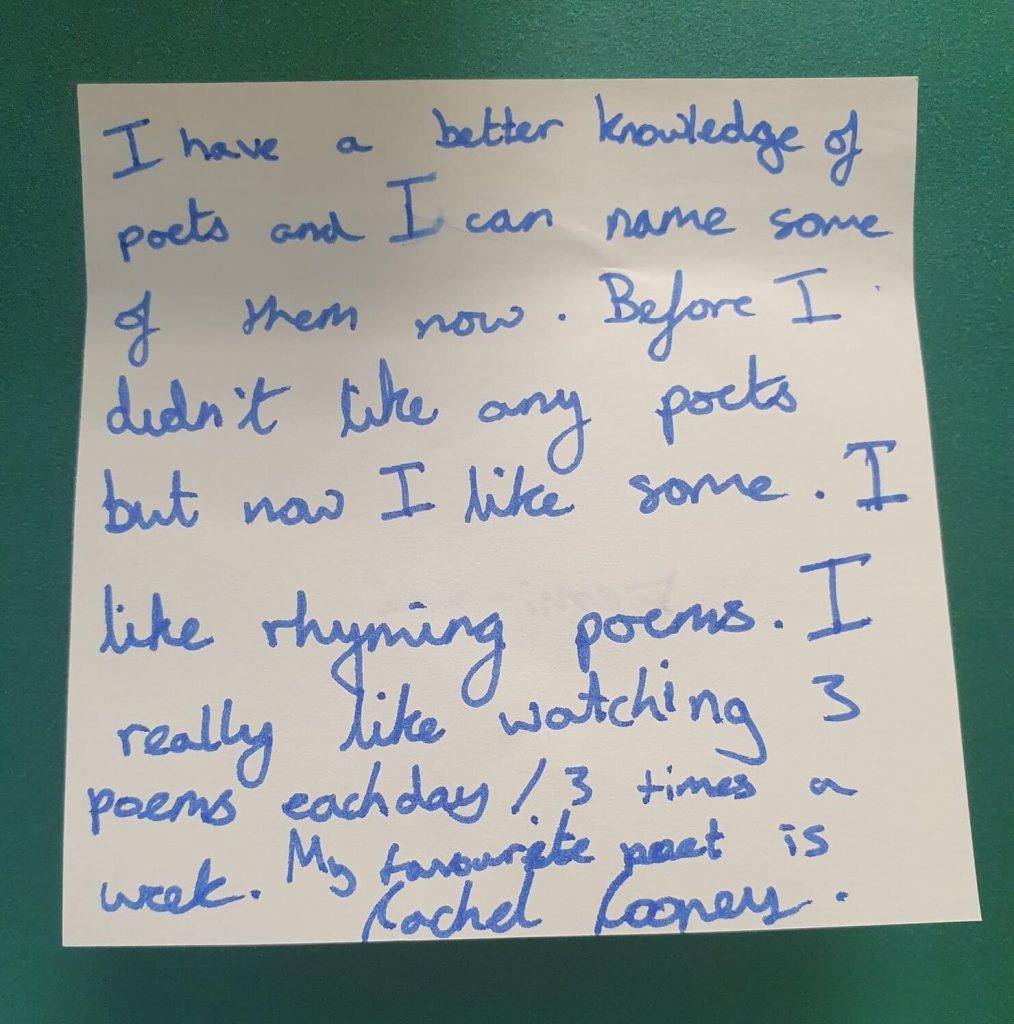

Teachers and children tracked their poetry journeys over the course of the entire project. They recorded their developing thoughts and feelings about poetry. They also shared poets and poems that they were introduced to and whose work they particularly enjoyed.

The impact of this was evident in every school. All the teachers felt better able to provide their pupils with a wider range of poetry. This was both in lessons and for independent reading.

When children were exposed to poetry, and when they could access poetry for their independent reading, it increased their engagement with poetry and the time spent reading it independently.

Poetry in action

Valerie Bloom’s session focused on responding to poetry through performance. This was followed by the schools shadowing CLPE’s Poetry Award, the CLiPPA.

For three weeks, teachers incorporated a focused poetry unit into their curriculum. They drew on the teaching plans and video resources provided by CLPE.

As part of the scheme, children learned poems from one of the collections shortlisted for the award. They recorded performances of these to submit to the judging panel. The performance aspect particularly engaged children.

Another important part of the training was exploring effective approaches to writing poetry with children. Valerie Bloom introduced teachers to a range of different forms that children could easily explore and replicate for themselves. Matt Goodfellow’s session looked at how to encourage children to write in their own voices and about their own lives. This proved particularly impactful for both teachers and children. They learned how important it is to be able to express themselves, their lives and experiences through the freedom of writing. The children also found it satisfying to write about what they wanted to.

Observing the results

Evaluation of the project showed how much the course had developed teachers’ subject knowledge and changed their perception of how poetry could (and should) be taught. The most significant impact was on children who had previously been seen as not engaging in literacy sessions, those who had previously been seen as needing additional support, and disadvantaged pupils.

Teachers also felt empowered to go back to their own schools to deliver CPD to their own staff teams based on the subject knowledge and activities they had gained as part of the programme, developing sustainability in the wider system.

We have combined learning from the initial survey and the research project in a new edition of our Poetry: What We Know Works booklet.

We’ll also be continuing to provide poetry CPD for schools on our poetry course in association with Macmillan and led by award-winning poet Kate Wakeling.

Schools can register to shadow the 2024 CLiPPA to be in with a chance for their children to perform on the stage of the National Theatre with this year’s shortlisted poets.

Inspiring collections from the project and 2023 CLiPPA shortlist

- Blow a Kiss, Catch A Kiss by Joseph Coelho, illustrated by Nicola Killen: A wonderful example of the joy of early play with rhyme and song.

- Caterpillar Cake by Matt Goodfellow, illustrated by Krina Patel-Sage: The perfect introduction to poetry for children at the earliest stages of reading.

- Marshmallow Clouds by Ted Kooser and Connie Wanek, illustrated by Richard Jones: A celebration of the natural world and the power of poetry to express our connections and experiences with the world around us.

- Stars with Flaming Tails by Valerie Bloom: A veritable feast of poetry from one of the country’s best known and most highly regarded children’s poets, with a specific section focused on poetic forms.

Even more resources

- Bright Bursts of Colour by Matt Goodfellow, illustrated by Aleksei Bitscoff: From the genuinely funny to the deeply emotive, a collection with something for every child to enjoy.

- Hot Like Fire and Other Poems by Valerie Bloom, illustrated by Debbie Lush: A rich range of poems, some in Jamaican Creole, some in standard English, which bring light and life to diverse aspects of everyday life.

- Let’s Chase Stars Together by Matt Goodfellow, illustrated by Oriol Vidal: A poignant, powerful and uplifting collection, showcasing the power of poetry to work through experiences and express emotions.

- The Big Amazing Poetry Book, edited by Gaby Morgan, illustrated by Chris Riddell: A brilliant introduction to 52 fantastic poets, packed with different styles of poetry from a wide range of voices.

Charlotte Hacking is the learning and programme director at the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE). She led and developed the CLPE’s Big Amazing Poetry Project, designed to highlight the importance of poetry as a vehicle for improving children’s engagement in and enjoyment of reading and creative writing in schools. Get the latest news from the CLPE on X @clpe1 or visit clpe.org.uk.

How to teach verse novels

Verse novels are a fantastic, immersive way to get both teachers and young people feeling comfortable with all the ways in which poetry moves people.

The English education system’s focus on exams has piled pressure on teachers to teach writing in a way that ticks governmental boxes for so long, that real creativity can often be stifled. This is a huge source of frustration for educators yearning to let young minds express themselves.

As a former Y6 teacher, I understand the pressures on both teachers and pupils each time anyone picks up a pen in the classroom. Poetry provides a different space where, I believe, teachers can facilitate creativity in writing such that children can really express themselves and write in their own voice.

Why verse works

Verse novels are succinct, to the point and pared down. They allow the writer to distil emotion into a few hundred pages in a way that won’t overwhelm a young reader.

There are many, many incredible examples of verse novels published in the last few years that can be read in both primary and secondary classrooms. Their approachable range of subject matter allows readers to feel that poetry can do whatever it wants to do and is not bound by age-related expectations.

How to teach a verse novel

I think the ideal way for a verse novel to be shared in classrooms, when budgets allow, is to use a class set, with children following along as their teacher reads. The beauty of this is that pupils can see exactly how poetry differs from other sorts of writing on the page; how a poet makes use of space and form to convey emotion. If you don’t have budget for a class set, you can use a digital copy of the book or visualiser to share the text with the whole class on a screen as you read.

Children will also be exposed to how writers can manipulate words and language in a way that can capture accent and dialect. In my verse novel, The Final Year, for example, the main character, Nate, speaks in the voice he has grown up with. It is far, far removed from Standard English. This is an excellent way to start discussion in the classroom about cultural heritage and identity.

Encourage discussion around how poets can reject the notion that we should all be forced to speak in a way that was agreed upon by a small group of rich, powerful people a few hundred years ago. Very quickly, a class (and possibly a teacher) who might begin the book feeling nervous about poetry, can begin to understand the endless possibilities that poetry offers.

Building your verse library

I would always recommend teachers have a range of poetry to hand, from single-voice collections to anthologies containing lots of different voices. Children will gain most from this variety of material if they hear poetry daily, as they will then be constantly learning how different poets do different things – all of it poetry.

There is a huge number of free poetry resources available online that can beam poets into classrooms for free. The Children’s Poetry Archive is a fantastic resource, which has gathered audio recordings of some of the best children’s poets and then stored them online for free.

The Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE) website also has an awesome array of resources. It includes over 500 videos of poets reading their work and talking about why poetry matters to them – giving hints and tips to young writers who want to begin their own writing.

Award-winners

As well as this, the CLPE runs its yearly poetry award (the CLiPPA), which creates a shortlist of what it considers to be the best books of poetry for young people published each year. Amongst the poetry collections, there are often verse novels.

The CLiPPA is the only award solely presented for published children’s poetry in the UK, and I’m proud that my books Caterpillar Cake, Bright Bursts of Colour and Let’s Chase Stars Together have all been shortlisted for it. CLPE produces lesson plans and video resources for each book on the shortlist, which are free for any school to download on their website.

The CLPE also runs a shadowing scheme, where schools send in videos of children performing a poem from one of the shortlisted titles. These are judged and the winners get to perform on stage at the award show, at the National Theatre in London, alongside the poets.

Being shortlisted for the CLiPPA and involved in all the activity around the award has provided me with a much larger platform and audience for my work than I’d normally have had, as well as an invaluable opportunity to work alongside other poets and writers. It’s great to have the videos and resources from CLPE to recommend to schools, and it’s always fantastic to see the impact of the shadowing scheme and to meet the winning schools.

Getting all kinds of poetry into the classroom is such a powerful and important thing to do – and verse novels are a perfect way to begin the process. Read them for pleasure in the classroom and discuss how they make the pupils feel. Let poets’ voices be heard, in order to unlock the authentic voices of the young people you teach.

How to make the most of verse

- Try to expose pupils to poems every day. As well becoming more comfortable with poetry as a genre, they will begin to identify and appreciate the variety of ways poets write.

- Read verse novels as a class and for pleasure. Modelling the text for the children is invaluable in helping them understand how the poet intended their writing to be interpreted.

- Make sure children can see how poetry looks on the page as it is read aloud. If you don’t have budget for a class set of a book, use a screen to share it instead.

- Open class discussions about how poetry is like mercury, flowing whichever way it wants into any shape and space.

- Use as many available resources as you can to get a good range of contemporary voices into the classroom. Let children see that poetry is for everyone.

- When teaching a new verse novel, make sure you read it before the children do. Verse novels often have powerful and difficult themes that you may need to discuss and think about as a class.

Matt Goodfellow is a poet and former primary teacher. His first middle-grade verse novel, The Final Year, is out now.