Adaptive teaching – What it looks like & why it’s important

Adaptive teaching is about making reflective, real-time observations that allow you to change your teaching on the go…

- by Teachwire

What is adaptive teaching and how is it different to differentiation?

While many of us are familiar with differentiation, adaptive teaching seeks to go further and iron out some of differentiation’s unintended consequences.

Differentiation aims to tier lessons according to ability – this consequently leads to us having lower expectations for some and widening the attainment gap. On the other hand, adaptive teaching aims to get all students to the same level of understanding and skill.

You’d usually consider differentiation while planning your lesson or topic. Adaptive teaching is about making reflective, real-time observations that allow you to change your teaching on the go.

Adaptive teaching in practice

Firstly, before you worry about another layer of work, the chances are you are doing a lot of this already. Have you ever explained one idea or concept in two different ways after the first fell flat?

Have you ever provided extra examples, or an analogy, presented information in a different way or added more exercises to a lesson as a result of identifying an understanding weakness?

“The chances are you are doing a lot of this already”

Any time you modify your teaching or planning, as a result of identifying learning needs, you are practising adaptive teaching.

However, in order to ensure you’re doing adaptive teaching properly, it’s important not to solely rely on picking up on issues as you go along. Instead, you need to insert points into your lesson where you actively assess students. This means you’ll be supporting them in relation to their actual needs.

Micro assessments

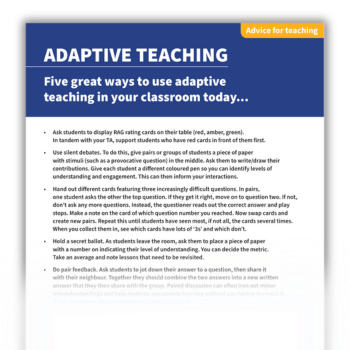

With this in mind, step one is to know what students have understood and what they’re still struggling with. Building in moments of micro assessment – the kind that doesn’t need to be marked – will help you to do this. Three examples of this are:

- RAG rating cards – ask students to hold up the colour (red, amber, green) that best represents how they view their understanding after you’ve taught a topic

- Mini whiteboards – pupils write answers to questions, and all hold them up at the same time

- Voting – break down the lesson into its elements and ask students which they found the easiest/hardest

If you find that your class is generally progressing at the same rate then it’s easy – you move on or re-visit as needed. If the response is varied, this is where differentiation comes into play. However, you want the kind of differentiation that supports everyone with their personal learning gaps, rather than differentiation pitched at varying levels.

Adaptive teaching resources

The following ideas are ways to use differentiation with the aim of achieving deeper engagement for everyone.

Targeted worksheets

Have a variety of worksheets on standby to give out at the end of sessions or topics. This works particularly in key subjects such as maths and English. Hand out the tasks based on where you’ve just assessed each student’s weakest area to be.

Homework

Homework can also be an incredible tool for meeting the needs of a varied class. Ask children to complete revision tasks based on the elements they found the most challenging, rather than setting whole-class worksheets.

Group work

Place students into groups to complete targeted activities. Alternately, give extension tasks to those who fully understood the lesson. This will stretch and challenge the most able.

When one size doesn’t fit all

Even if the majority of your class is struggling with the same topic, one approach may not necessarily benefit all. For one person an analogy or example might help. Another may understand better when they see a diagram or video. Some may want a practical task.

It can be difficult to provide this range of options at the drop of a hat when you discover that your class simply doesn’t understand fractions. So what do we you?

If a lesson flops, park it and prep it with a different approach for another day. There’s no point continuing if it’s not working. As you prepare, consider how you can give information in different formats.

“If a lesson flops, park it and prep it with a different approach for another day

In your English lesson, could you watch a performance of the text you’re studying? Can you give students a copy of the text that they can follow along with as you read it out loud?

This way, children have now ‘received’ your base text in a number of different ways.

In science, could you support diagrams with a video and then follow this with a practical task? This allows pupils to experience a topic they are struggling with via a number of different methods. Hopefully one of them will click.

Can you physically explore the maths you’re studying through blocks, counters or shapes before you look at them on a page?

You probably utilise many of these methods already, and not every lesson requires this range of planning and activities. However, it’s good to have ideas up your sleeve when you’re teaching harder-to-grasp topics to ensure pupils have a full and deep understanding. These tricky areas might change every year, of course, depending on your cohort.

Getting the most from adaptive teaching

Of course, adaptive teaching, like any approach, is imperfect. Knowing the potential issues can help you to mitigate them.

If you want children to honestly assess their level of understanding, they need to know that to not understand something is OK. Reiterate that learning is a process and that people have different strengths in different subjects.

Make sure that your classroom is a kind, encouraging place to be and that you acknowledge strengths and weaknesses, rather than criticise them.

This may sound obvious, but with the pressures of class sizes, behaviour and workload all crashing together, so often a classroom can become a place of pressure and stress, for students as much as the teacher.

As a parent, I can attest to the transformation my daughter underwent when she spent time with a teacher who constantly encouraged her to ask for help if she was struggling.

“Adaptive teaching, like any approach, is imperfect”

For adaptive teaching to work well you need to really know your students. with class sizes often exceeding 30, this is a genuine challenge for primary teachers. However, adaptive teaching should also help with this, since it takes time to get a snapshot of each student’s level of understanding.

If, for example, you opt to use the RAG rating approach, you should start to see patterns forming. This will allow you to act accordingly.

Retrieval practice

While immediately revisiting work that has been hard for students sounds like a great plan initially, research has shown that spacing content leads to better long-term recall and understanding.

If you allow students to almost forget content, and then revisit it, students will exert more effort in retrieving the memory. This helps to cement new ideas more successfully in the minds of learners. In the classroom, this means discovering what students have not fully grasped, but waiting a few weeks after the initial lesson before you go over it again.

While some criticise differentiation for capping the ambitions of so-called ‘weak’ learners, could it be said that if adaptive teaching aims to get all students to the same level, we’re failing to push our very best learners?

As with all approaches to teaching, a mixed economy is so often the best approach. Adaptive for all, with differentiation for the top, might be the best way to utilise this ambitious approach to teaching.

Hannah Day is a teacher in the West Midlands with a specialism in art and design. Read about five more adaptive teaching strategies to try.

PE and adaptive teaching

Phil Mathe explains why there’s a better way to ensure that every student gets something out of your PE lessons…

I have a habit of telling things as they are. Of being blunt and direct. And when it comes to differentiation in PE, I’m particularly narrow-minded. I don’t like the term, and don’t believe we should still talk about it – or do it.

It should have gone the way of learning styles, whole language approaches or brain gym. Here, I will try to explain to you all why differentiation in PE should go the way of the Dodo.

Captains and novices

No one teaching PE would deny that it’s crucial to implement strategies that ensure all of our pupils benefit from their lessons, regardless of their individual abilities. Just as no one would take issue with the idea that interactions between students of different proficiency levels can significantly impact upon their subsequent learning and progress.

More so than most subjects, PE is liable to see students of very different abilities directly interacting, and potentially affecting each others’ learning and advancement in the process. How can PE teachers ensure that everyone gets something out of their lessons – from the school captains resentful at the less capable getting in their way, to the reluctant novices put off by the intimidating capabilities of their more sport-minded peers?

The answer is that we need to come up with effective, dynamic and exciting ways of solving the issues that differing ability levels can pose. We must find a place where all our pupils can thrive and flourish in our lessons, regardless of capability or motivation.

Resource-intensive

The concept of differentiation in education was first popularised in the 1990s by Carol Ann Tomlinson, who had introduced it as a way to address students’ diverse learning needs by adjusting instruction, content, and assessment to accommodate this variability.

Her work has had a significant impact on teaching practice worldwide. Indeed, the teaching world owes Tomlinson a debt of gratitude for promoting individualised focus within teaching and learning. And yet, the world always moves on, and today we now recognise both the benefits of the differentiated approach and its limitations.

One particular challenge is the time- and resource-intensive nature of effectively implemented differentiation – particularly in large groups with limited support, such as those you’ll regularly find within PE spaces. Teachers will also always face some practical constraints when altering their methods, modes of instruction, course content and assessment processes to cater directly to individual pupils – not least potential disparities in provision between different groups and individuals.

Furthermore, differentiation can (inadvertently) lead to the reinforcement of fixed mindsets within pupils, and a certain (often misleading) self-perception of their indicative ability level. All this can then result in differentiation becoming oversimplified or tokenistic, rather than the thoughtful, meaningful adaptation Tomlinson originally championed.

So, if differentiation has had its day, what should we turn to for the kind of individually-focused provision that will help us fully realise our pupils’ learning opportunities and true potential?

Dynamic adjustments

Adaptive teaching has emerged in recent years in response to advancements in educational research, and a growing understanding of the potential to enhance instruction through ever-changing educational strategies, reacting to pupils’ individual needs at any given moment.

Various researchers, educators and academics have contributed to developing and discussing adaptive teaching practices over time, establishing the place in the framework of educational pedagogy that it holds today.

Differentiation involves tailoring instruction, content and assessment to accommodate individual students’ diverse learning needs and preferences within a teaching space. Adaptive teaching encourages us to adjust our instruction and provision dynamically, in response to students’ progress within individual teaching moments.

The emphasis is on providing personalised learning experiences, and maintaining a comprehensive set of strategies we can implement ‘in the moment’ – both to drive learning progression, and to promote a more positive, success-driven environment where student progression is appropriately supported at an individual level.

Differentiation in action

Let me provide a practical example of each, all within the same learning context, so that you can hopefully appreciate the difference.

A basketball lesson focused on, say, basic dribbling could be differentiated through a variety of methods. We could group the pupils by ability within a class, so that students are working towards specific goals set for each group’s ability. The less confident could be tasked with dribbling in straight lines, while the more confident and capable can practice changing directions or pace.

Alternatively, you could differentiate by task, where a wide variety of outcomes are set for different pupils, depending on their ability or confidence. You could then change the equipment to offer additional support or scaffolding to pupils for whom the task is more challenging – or, you could add or reduce pressure to provide a higher or lower level of challenge.

Yes, you can differentiate in many ways within just this lesson – but each method will ultimately be designed and set within the lesson plan before any teaching commences.

A different lens

On the surface, at least, there doesn’t seem to be much wrong with this. If we’re honest, this is the way we’ve approached our PE for years. But when you stop to really think about what we’re doing, the issues become glaringly apparent.

Differentiation is ‘static teaching’ – assuming we know what our pupils will need before we even see it in practice. Yes, we all know our classes, and what they are or aren’t capable of – but this pre-planned and regimented approach allows little flexibility to adapt in response to things we see happening in front of us. So let’s look again at the same lesson – only this time, through a different lens.

We set out with one overarching objective for all of our pupils (without prejudging them) and give them all the benefit of the doubt. As the lesson progresses, we establish data in the form of observation and questioning to identify where additional challenge or support is needed – and we then provide it.

In many ways, this will look familiar – inasmuch as we’re changing the pressure, the equipment and objectives.

What we’re actually doing, however, is allowing the progress of the lesson to determine the next progression. We’re still adapting our teaching to allow learning to happen in every pupil, but also encouraging a sense of success and progress towards a more common goal.

This willingness to identify and adapt is surely a more fair and inclusive approach, compared to simply deciding what our pupils can do before we even prove it to ourselves – or them.

Worth and value

Ultimately, we’re all striving for a few key things in our PE provision. We’re looking for inclusion, a sense of worth and value within our pupils. We’re striving to imbue our lessons with a sense of support and security, and looking out for opportunities to praise and recognise success in every child.

Adaptive teaching gives us all that, and so much more. It:

- reduces planning pressure

- helps us develop uniqueness in our teaching

- builds creativity, and in turn, engagement

- helps us build relationships with pupils based on praise and success

- puts our pupils – not our planning – at the front and centre of everything that we do

5 steps to adaptive teaching

- Know your outcomes

Be clear as to what your overriding objectives for all pupils are. Think about how you’ll support each child so that they can get as much success from your lesson as possible. - Know your barriers

Reflect on what might prevent your pupils from reaching their objectives, and what adaptations you could make to support their progress. - Identify stepping stones

What steps towards overall success can you highlight and praise when pupils achieve them? This will support a success-driven atmosphere in your classes. - Reflect, always

Use a few spare moments after each lesson to reflect on how the lesson went, the individual and organisational successes you saw, what worked and what didn’t. Use this reflection to shape your next engagements with that class. - Don’t try to be perfect

Adaptive teaching is a skill that we’re all still learning. Be kind to yourself and don’t expect perfection. Develop a toolbox as you progress, and don’t worry if things don’t always work. The fact that you’re trying shows how important your pupils’ success is to you.

Phil Mathe is a PE teacher, researcher, speaker and author of the book Happiness Factories: A success-driven approach to holistic Physical Education (John Catt, £17); follow him at @PhilMathe79_PE

Maths and adaptive teaching

Is adaptive teaching just differentiation under another name? Absolutely not, says Mike Askew…

A couple of decades ago, when England had the National Numeracy Strategy, Osted noted that differentiation within mathematics lessons was common and that ‘Teachers usually organise pupils into three ability groups’.

Since then, with the focus on all pupils mastering more of the mathematics curriculum, the language has changed, with Ofsted focusing on adaptive teaching rather than differentiation.

So what are the distinctions (and similarities) between these two ideas?

Both have the same underlying intent: to help pupils make progress; and adaptive teaching does involve a degree of differentiation. But adaptive teaching is not simply differentiation in new clothes.

The problem with classic differentiation

To clarify the essential differences, it’s helpful to address what I would call ‘classic differentiation’ – the practice of grouping pupils by their perceived ability or level of attainment, and then assigning different work to different groups according to their needs.

The problem with these practices, as many research studies have shown, is that over time, the spread of mathematical attainment in a class often increases rather than decreases.

“Adaptive teaching is not simply differentiation in new clothes”

Unlike classic differentiation, adaptive teaching is about helping the great majority of pupils succeed at the same learning outcome.

The key question behind adaptive teaching then is not, ‘What is the need of this pupil?’ but, ‘How must I change my teaching to enable all pupils to access the ideas being taught?’

To answer this question, adaptive teaching has to operate at two levels: the intended (the planning for teaching) and the implemented (the moment-to-moment classroom interactions).

Planning for adaptive teaching

I’ve written before about the distinction between task and activity – a task being what pupils are asked to do, and activity being the mathematical thinking a task can potentially provoke.

Consider, for example, this ‘consecutive numbers’ challenge:

- Jot down pairs of consecutive numbers, such as 3, 4; 15, 16; 37, 38.

- Add the numbers in each pair: 3 + 4 = 7 and so on.

- What do you notice?

- What do you wonder?

This is an unambiguous task, but beyond simply providing practice in addition, it has potential for considerable mathematical activity. For example, pupils will quickly notice that all of their answers are odd numbers. They may then wonder, Can all odd numbers be expressed as the sum of two consecutive numbers? What happens with three consecutive numbers?

Having worked through these ideas, and seen that both odd and even numbers can be expressed as the sum of consecutive numbers, pupils might go on to wonder:

- Given a number, can I figure out how to express it as a sum of consecutive numbers?

- Are there any numbers which cannot be expressed as the sum of consecutive numbers?

- Given a string of consecutive numbers is there a quick way to work out what their sum will be?

‘Consecutive numbers’ can thus lead to a range of deep mathematical thinking, but the set-up, the initial task, is one with which everyone will initially be able to engage.

Common ground

This is a task that brings as many of the pupils as possible into some ‘common ground’, from which further mathematical activity emerges.

Thus, a key question to ask when planning for adaptive teaching is: How can a task be initially set up so that the maximum number of pupils can begin to engage with it?

Allowing pupils access to concrete materials that might help them start on a task, is one possible strategy for creating common ground.

Another is to pose a task in a way that gives pupils some choice over their entry point into it. This can mean adapting closed tasks to be more open:

- Closed: Put a collection of numbers in order.

- Open: Write down five numbers that can be modelled with exactly three base ten blocks. Put them in order from smallest to largest.

- Closed: Solve a multiplication word problem

- Open: Choose two numbers to multiply together. The product must be greater than 100, and an odd number. Write a problem to go with your numbers.

- Closed: Complete a page of additions of fractions.

- Open: Write down two fractions with different denominators. Find the sum and difference of these fractions.

Adaptive teaching in the classroom

The main actions of adaptive teaching are the ‘on the hoof’ mediations and interventions made in real-time teacher-pupil interactions. Generally, such ongoing interactions address one or the other of the following aspects of working:

1. Task completion – helping pupils to succeed in the task.

Strategies that support helping pupils complete a task include:

- reducing the complexity or difficulty of the task

- helping pupils to focus on the most relevant aspects of the task

- suggesting some concrete materials that might help

2. Promoting higher-order thinking (mathematical activity) – helping pupils come to see mathematical generality in the specific task. As well as asking, ‘What do you notice?’ helpful questions include:

- Can you make up an example to test what you have noticed?

- What if you changed….?

- Can you write down a conjecture about what you have noticed?

Alas, there is no magic formula for which type of intervention to adopt at any time; too much focus on task completion and pupils may not learn anything, too much focus on higher-order thinking and they may get frustrated.

That’s that biggest challenge of adaptive teaching; but also the greatest joy when a decision works.

What adaptive teaching is and isn’t

- Adaptive teaching involves real-time differentiation.

- At its best, adaptive teaching builds on what pupils can do. Children’s different levels of experience and ability are seen as ‘opportunities to learn’ rather than ‘obstacles to overcome’.

- Pupils can succeed at tasks without necessarily learning the intended mathematics. Adaptive teaching involves formative assessment, with questions such as: Can you explain to me how you would do a similar problem? What was easy about this? What was hard? What questions do you have about doing this?

- Adaptive teaching can go beyond the task at hand and help pupils become self-adaptors and to develop mathematical aptitude. Adaptive questions that pupils can adopt for themselves include: What do you know? What do you want to know? What have you seen before that is like this? What could you change to make this easier to do?

- Research shows adaptive teaching that focuses pupils on the general mathematics behind a task can not only increase pupils’ success in that activity, but also have a pay-off in increasing pupil success with harder questions (see PISA’s Ten Questions for Mathematics Teachers).

- Adaptive teaching is NOT about catering to pupils’ supposed preferred ‘learning styles’ – this idea is now largely discredited by psychologists.

- A large part of adaptive teaching is carefully listening to pupils and watching them work. Effective adaptive teaching builds on what pupils are currently doing, rather than simply showing them what to do.

- Help with simpler problems is likely to be more direct. Harder problems require subtler adaptive teaching, so that the thinking is not taken away from the pupils.

Mike Askew is adjunct professor of education and Monash University, Melbourne. A former primary teacher, he now researches, speaks and writes about teaching and learning mathematics. Visit his website at mikeaskew.net.