Film and media studies – Let’s celebrate their transformative power

Jose Sala Diaz highlights how film and media studies can truly transform learning…

- by Jose Sala Diaz

- Head of media at The Priory School, Hitchin

In an era when every interaction and hobby feels like it’s been distilled into ‘content’ – i.e. a media substance that can be controlled and monetised – film studies and media studies at GCSE stand tall as subjects capable of leading a paradigm shift.

That’s because they not only teach students how to really see what they see around them, but also how to shape their own representations, and harness their creative skills in the service of imagining better, more optimistic futures.

Learning how to see

In media and film studies, we teach that no image comes from nowhere. Students learn how to analyse audiovisual texts from a critical and aesthetic viewpoint based on five main areas:

- microelements

- representation

- audience

- industry

- contexts

The popular Netflix series Stranger Things, to flag up a topical example, relies heavily on fabricated nostalgia for the 1980s. This is something that Warner Bros has also attempted to do, albeit in different ways, with the Harry Potter series.

Disney has gone down a similar route with its live action remakes. The Lost Boys, on the other hand, released in 1987, did more to channel the cultural concerns of its time, including the fear of crime, rising divorce rates and perceived decline of the traditional family unit that characterised the Reagan era. At the same time it demonstrated a great understanding of horror conventions.

See also 1955’s Rebel Without a Cause. This echoed the then-popular perception of teenage subcultures as groups of criminals without a future. Simultaneously, it contrasted the nihilism of its imagery with its beautiful rendering in Technicolor.

Back here in the 21st century, Whiplash is an excellent film to show students when discussing toxic masculinity. It culminates in an ending built around our audience perceptions of individualism and success.

Then there’s Skyfall (2012), the 23rd entry in the long-running James Bond franchise. This deals with a generational clash between old and new, while pointedly commenting on our modern-day attitudes to digital technology and the British Empire.

Finding connections

The films cited above have all been discussed in our school’s classes, if not explicitly included in the GCSE and A-Level Film specifications.

People say that whoever controls the media controls the culture. Media and film studies are about how fiction reflects reality, usually following a series of very specific choices.

The study of media and film helps students explore precisely how and why those choices are made. It can show them how the practice of video editing – a foundational media and film element – can suddenly become hugely important in the context of a Donald Trump speech broadcast by the BBC, to such an extent that the BBC’s director general feels compelled to resign his position.

Blair Waldorf, the young New York socialite portrayed in the Gossip Girl novels and subsequent TV adaptation, once remarked that ‘Fashion is the most powerful art form’ because it ‘combines movement, design, and architecture’.

I would, in turn, suggest that media products are a form of art. This is because they can be both medium and form in a given context.

We teach media and film studentsto find and trace connections, accidental or otherwise. We explain how Dua Lipa, in her song ‘Illusion’ and its accompanying video, is engaged in a conscious dialogue with both a prior Kylie Minogue music video and a 1992 Time magazine cover celebrating that year’s Olympic Games.

This is an exercise in intertextuality which proves that nothing is born from a void. (This is regardless of what those feverishly discussing the latest trending topic might try to tell you).

The more that media students get to explore, the more references they’ll be able to spot and distinguish in the products they consume today.

“But I just watch videos on my phone!”

At one time, many assumed that the rapidly expanding availability and bandwidth of the internet would enable near instant access to virtually every film ever made, and encourage students to expand their cultural horizons. But that’s not quite what’s happened.

While it is indeed technically possible for students locate virtually every film or series ever made somewhere online, teachers have found themselves needing to fight back against a strain of audiovisual homogenisation.

Everything often looks the same. Everyone seems to be consuming much the same things (those ‘things’ often being daily viral videos on TikTok).

Students see worse than ever. But by that I don’t mean the overlit shots of so many modern movie productions, or those CGI effects that rely so heavily on post-production processes.

I mean the lack of internalised references that’s preventing this generation from consuming audiovisual texts falling outside of what social media algorithms serve up for them.

How to watch

That’s why it’s more important than ever that we educate students on how to watch (and, indeed, how not to).

Attention is the currency of our times. It’s up to teachers to recommend, introduce and open up paths of discovery that lead to different creatives and their unique perspectives.

The number of students unfamiliar with the likes of Sofia Coppola, Michel Gondry or Guillermo del Toro and their work is huge. That’s despite those creators generally being considered to not be that obscure.

It’s been a pleasure seeing how well the students respond to these three directors’ very different directorial styles.

I believe that despite all the endless scrolling on their phones, our students are still able to recognise talent, personality and beauty when they see it. It makes sense to have them analyse what makes certain works appealing.

Now especially, would it not make sense to challenge students to become critical thinkers?

The practical element

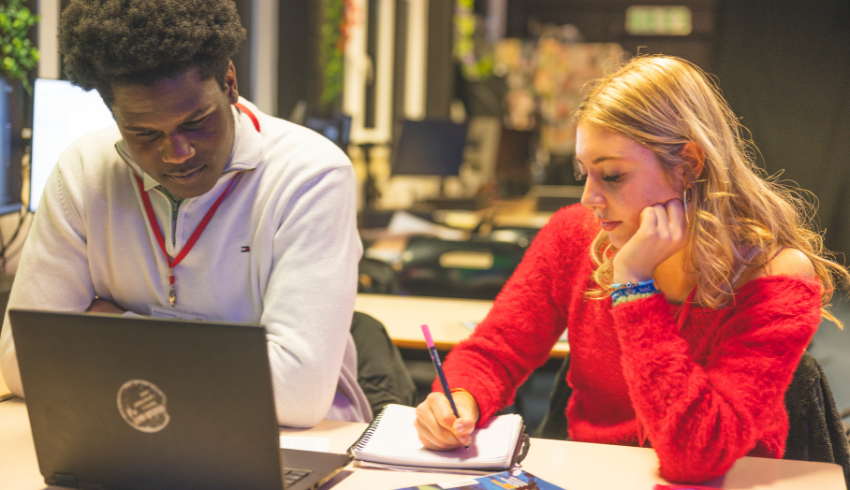

Finally, it’s worth highlighting that 30% of film and media grades are based on coursework. In film, students have to create an introductory sequence to a suggested longer work.

In media, we task them with producing a short music video, a magazine or the opening part of a TV series. This demonstrates their understanding of what makes each medium unique, and how they can challenge codes and conventions.

This practical element teaches students that everything they consume on their phone screens involves an immense amount of invisible yet highly creative work behind the scenes, courtesy of a large creative industry that’s powered by thousands of people.

The students’ practical work is also essential because the art of storytelling sparks cognitive development.

Lack of empathy

A key issue for this current cohort is their tendency towards self-isolation and lack of empathy when compared to their generational predecessors.

Putting your phone down for two hours and placing yourself in someone else’s shoes requires effort. It demands that students recalibrate their ability to focus, and reorient how they see and think.

The challenges involved in representing an idea, person or theme, and in understanding the ‘other’ are rewarded during this coursework process.

It requires them to build their own representations and to develop their own voices. From initial storyboard drawings, through location photography, shot composition, set design and visual effects work, these students get to choose how they want to be seen. They have the chance to become creators themselves.

At a time of great uncertainty regarding authorship and the algorithmic forces that distribute the content we consume, we shouldn’t treat lightly the fact that we can teach students such abilities.

Just as we should resist the notion of ‘cinema’ being reduced down to ‘content’, we should ensure that students can’t be reduced to mere nodes picked up by algorithms. Because if our students don’t choose how they want to be represented, someone else will do it for them.

Jose Sala Diaz is head of media at The Priory School, Hitchin. The photos used to illustrate this article were all made by media and film students at the school.