Spelling tests – Why do we still make kids do them?

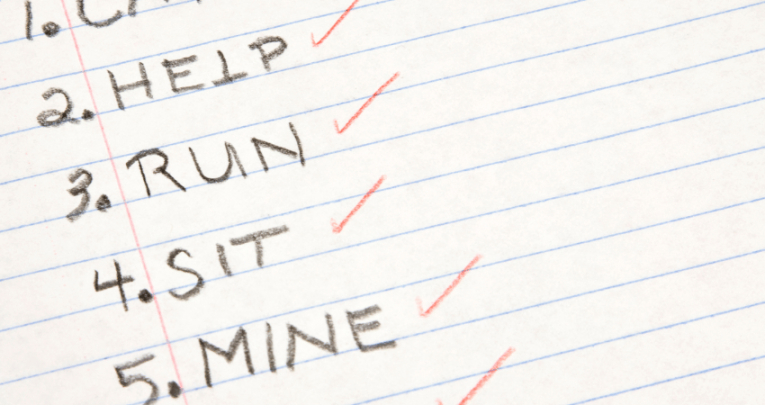

The dreaded weekly spelling test is causing serious self-esteem issues for pupils across the country. For what purpose, asks Dan Batchelor…

- by Dan Batchelor

- Primary teacher and author Visit website

As we all know, neurodiverse children are becoming increasingly recognised in the classroom, along with our understanding of their needs. We spend hours differentiating lessons, creating accessible resources, and prioritising children’s wellbeing (rightly so). Yet, with spelling tests, we are stuck in the past. So why do them?

I am dyslexic (diagnosed at 17). I hated the weekly spelling test as a child, and as a teacher, I hate putting my pupils through it.

The more time I have spent thinking about the issue, the more I have realised it isn’t about being dyslexic at all. It’s about what the tests actually stand for.

A child can be creative and write for different purposes, yet at the end of Year 6, part of the final judgement of seven years of learning comes down to 20 random spellings.

What’s the point of spelling tests?

Before attempting to list the reasons why spelling tests shouldn’t exist without rambling, I want to make it clear: I’m not saying spelling is pointless, just the tests (unless you are in a spelling bee).

I’m also not saying spelling shouldn’t be taught and practised – it’s important to be able to recognise and correctly use homophones, prefixes, suffixes, and changing word classes, and so on.

I’m simply saying a child’s final outcome shouldn’t be judged against a test, and children shouldn’t be made to sit through it.

As someone who is dyslexic, I never felt more stupid at school than during the weekly test. I would practise and still do “terribly” Furthermore, if you asked me to spell those random words a week later, I would do even worse.

So, my first question is: if the information isn’t retained, what is the point? Not only this, but I also have an identical twin (cue the violin), who happened to be very good at spelling. I always compared myself to him, which only lowered my self-esteem and confidence even more.

Now, not everyone is a twin, but we can all relate to comparing ourselves to those around us. Why have something in place that can do that to a child’s self-esteem?

Everyone knows dyslexia isn’t a lack of effort or intelligence; it’s just a learning difference. It can even be a strength: many dyslexic people are incredibly creative thinkers, strong visual learners, and great problem-solvers.

Not only am I a teacher, but I also have a published book. I don’t say this to make it about me; I say this because, as an eight-year-old staring at “3/10” on my weekly test, I never would have thought this possible.

Why? Because I believed that to be a good writer, you needed to be a good speller. Little did I know, dyslexia wasn’t the barrier; my perception of what a writer should be was.

Putting children off

In today’s world, there’s so much support available, yet we send children into a spelling test blind. We wouldn’t do that in any other aspect of learning.

Rather than making children feel stupid, we should make them feel supported. Why put barriers in front of a six-year-old? No wonder so many children are put off reading and writing for pleasure.

Rather than putting up obstacles, we should be removing them with tools that are now readily available, such as typing or voice-to-text.

What needs to change

There needs to be a systematic change. I believe the emphasis should be taken off spelling and placed on reading and creative writing, whilst making learning accessible and relevant.

So, back to my original question: why do we still do spelling tests? As long as spelling remains part of the SATs, we are setting children up to fail by not practising them.

But by maintaining these tests, that is exactly what we are doing for dyslexic children (statistically, likely to be 1 in 5 pupils).

We wouldn’t put children through this in a PE lesson, nor for any other neurodiversity. So why is it that we haven’t moved forward with spelling?

How is it that 20 random spellings go towards the final judgement of a child’s learning? Time in schools is precious. Let’s remove the dreaded tests and use that time to help progress, not create unwanted stress for children.

Dan Batchelor is a primary school teacher and author. His first novel, Jack Palmer: A New Order (£10.99, Cranthorpe Millner Publishers), is out now.