What Teachers Need To Know About Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Anne Gilbert explains what schools can do in response to the relatively unknown, yet common condition of juvenile idiopathic arthritis…

- by Anne Gilbert

- Family support and health education leader

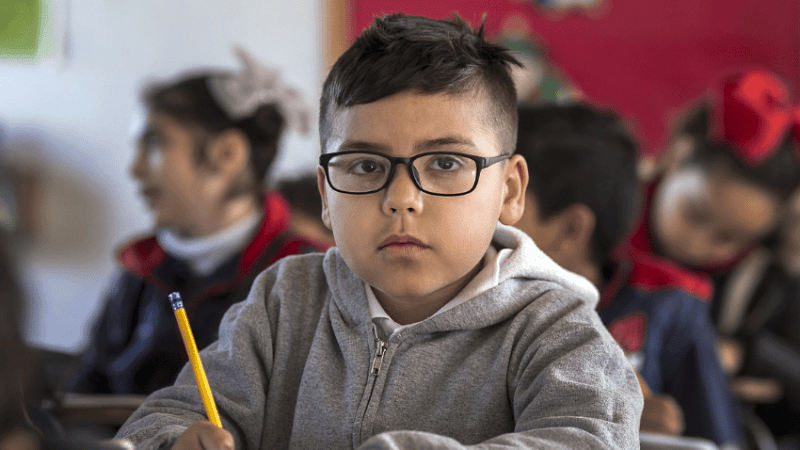

Auvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) currently affects over 12,000 children in the UK and is one of the most common causes of physical disability encountered during childhood, with around 1,500 under-16s newly diagnosed each year.

JIA may not be outwardly visible at all times, but flare-ups of the condition can come on suddenly – any staff member who works or is in regular contact with a child who has JIA ought to be made aware of their condition. If a child has JIA their affected joints can become extremely stiff.

Regular movement helps, so allowing a child to move around is essential. For a young child required to sit for long periods of time, especially on the floor, this can cause them a huge amount of pain.

Where this is the case, a simple solution many opt for is to simply let them sit on a chair, though this then draws attention to the child and can cause them to become self-conscious. Not all children will want their peers to know about this invisible condition that they have.

Schools and nursery settings can do much to support younger children with JIA via inclusive approaches that do less to mark children out as different. If your school decides to let a child with JIA sit on a cushion, for example, why not extend the same privilege to others in the class who want to share in it?

Playtime and PE

Many children with JIA will worry about everyday playground activities in a way that others don’t. Getting tripped up or jostled in the playground can cause considerably more pain for them than their peers, for example.

They may therefore ask to sit inside, which can be isolating. Schools can make a huge difference to their level of engagement by introducing playtime and PE activities that can reduce the risk they’re exposed to, while still allowing the child to be included. For all the risks involved, it’s important that children with JIA get to join and take part in PE lessons unless they’re having a flare-up or are feeling unwell – though the child and their parents or carers ought to be consulted on the nature of activity involved and how long they can take part for.

Timetabling

It’s difficult for schools to ensure their timetable meets everybody’s needs. If possible though, where a child has difficulty using stairs or walking long distances between classrooms, providing them with a timetable that take that into account will help enormously.

In exceptional circumstances, you may need to consider a part-time timetable that allows a child with JIA who is regularly and severely unwell for prolonged periods to still engage with school.

Staff training JIA is different to conditions such as asthma, diabetes or epilepsy in that staff require no specific training with regards to administering medicine to pupils, but they will need to have a general understanding of what JIA is and how a flare can be triggered.

Schools won’t need any specialist equipment, but for inflammation and sore joints a lot of children will get relief from an ice pack or heat pad and anti-inflammatory medication such as ibuprofen.

All schools should have a medical conditions policy which states how the school will care for any children with medical conditions, the procedures for getting the right care and training in place and who is responsible for making sure the policy is carried out.

Additional support

With support from their school, any child with a long-term condition or additional needs can apply for an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP), which have replaced Statements of Special Education Needs in recent years.

In many cases the process can take some time, but if granted, EHCPs will ensure that a child receives continuous provision and support whilst the child attends school. An EHCP could mean that a young person receives extra support during exams, such as more time or help with scribing.

If the child or young person has an occupational therapist who supports them with their JIA, we would recommend that the school use the OT to help with the EHCP while supporting the understanding of JIA throughout the school.

Parental engagement

JIA flare-ups can occur overnight and can make a child feel unwell for weeks, so there may be occasions when a child will be off school for multiple weeks. The child’s parents/carers and the school will need to maintain regular and open communication.

If JIA starts to impact upon a child’s attendance, the school can lend support by being mindful of its messaging about attendance to the family; standard letters demanding explanations when a parent has already been in touch will cause additional and unnecessary stress.

There is no known cause for JIA but the condition can be influenced by stress, making the child’s friendships, mental health and confidence levels key areas for schools to take into account.

The safe in school campaign

JIA-at-NRAS is among the organisations making up the Health Conditions in Schools Alliance (medicalconditionsatschool.org.uk), which has worked with the DfE to remind schools of their legal obligation to have a medical conditions policy.

Recent research by the Alliance found that just 11.5% of schools were able demonstrate that they follow said law – and of those that did, two thirds of the policies were found to be inadequate, missing key details such as staff training, how to safely include children with medical needs in all activities and, crucially, what to do in an emergency.

Anne Gilbert is youth and family services manager for JIA-at-NRAS (National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society); for more information, follow @JIA_NRAS.