Tier 2 words – What they are and how to teach them

Try using these strategies to decide which Tier 2 words to teach and how to go about it…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Tier 2 words bridge the gap between everyday language and specialised terms. Join us as we explore strategies to help students master these words to close the vocabulary gap…

What are Tier 2 words?

The tiered vocabulary framework was created by education researchers Isabel Beck and Margaret McKeown.

- Tier 1 – everyday, familiar words for those children who speak English as their primary language. These are often ‘caught’ rather than learned through direct instruction.

- Tier 2 – high-frequency, impactful language encountered more often when reading than used when speaking. These words are useful in multiple contexts and help children express themselves clearly and with precision. These are the words that you should be directly teaching during English lessons (and beyond).

- Tier 3 – The words we use when talking and writing about specific subjects or a particular field of study.

.png)

Vocabulary gap

Tier 2 vocabulary isn’t as specialist as tier 3 vocabulary, but nor is it as simplistic as tier 1 vocabulary. It’s not ‘cat’, ‘dog’, ‘mum’ or ‘keys’, and isn’t ‘longshore drift’, ‘pathetic fallacy’, ‘nucleus’, ‘leverage’ or ‘ratio’.

It’s the language in between; the kind of intelligent and sophisticated vocabulary that’s useful across all subject domains. It’s the language of The Guardian, BBC Radio 4 and educational documentaries.

Some families will transmit these words to their children by osmosis when speaking at the dinner table or around the house.

These are the words that will be missing for some disadvantaged children. This is possibly because their parents don’t have those words themselves, or lack the time to sit with them at mealtimes.

Tier 2 words are the words that create the vocabulary gap. They leave underprivileged students without the words they’ll need to understand new content, or express their ideas convincingly and with nuance.

Consequently, these students fall further behind every year because words are sticky, just like knowledge itself.

When a student knows the word ‘implicit’, it’s easier for them to then learn ‘imply’, ‘implied’, ‘implication’, ‘implicitly’ and ‘implicated’. From there, it’s just a hop, skip and a jump to ‘explicit’, ‘explicitly’ and ‘explication’.

Examples of Tier 2 vocabulary words

As an example, The Explorer by Katherine Rundell features several Tier 2 words in the space of one paragraph:

- summon

- cascaded

- assumed

- compulsory

- exasperate

Other examples of Tier 2 words include:

- pragmatic

- façade

- interconnected

- concentrate

- benevolent

- required

- maintain

Tier 2 resource packs

Help pupils build a rich and broad vocabulary from Reception to Year 6 with Plazoom’s Word Whoosh resource packs. Use them to clarify and extend children’s understanding of Tier 2 words, enabling them to make more ambitious and accurate language choices when speaking and writing.

Download a free Year 6 sample from Teachwire.

Choosing which Tier 2 words to teach

There are over a million words in the English language, so it is no wonder that teachers feel overwhelmed when choosing the words to form the focus of their vocabulary teaching. Answering these questions can help:

- Which words are most useful to children?

- Are any of the words transferable to other subjects or scenarios already familiar to pupils, allowing them to use these words more frequently? For example, summon and compulsory can both be related to a school context: it is compulsory to attend when summoned by the headteacher.

- Which words are vital to understanding the plot? For example, cascaded describes the motion of a fast-moving river, and therefore impacts on the main characters’ decision regarding the safety of building a raft.

- Which words are children likely to understand most easily? Choosing words for which there is a simple definition can help to save time.

- Do any of the words have interesting histories (etymology)?

- Would studying the morphology (root, prefixes and suffixes) of the word be of interest?

A wise combination of these factors can help clarify the process of choosing the ‘right’ words to study.

Sometimes, choosing words to focus on can depend on the text you’re using. For instance, The Explorer traces the adventures of four children stranded in the rainforest, following a fatal plane crash.

This, of course, is an experience you would hope that the children do not have first-hand experience of! Bearing that in mind, there may be additional words that become your focus for vocabulary instruction.

These are words that are not necessarily part of the text itself but will help the children talk about it. For example:

- tropical

- vegetation

- humidity

- peril

- jeopardy

- quest

One way you can test whether a word might be classified as Tier 2 is to imagine its Tier 1 counterpart. In this case, rather than peril or jeopardy the children might say danger. A quest may be replaced by a hunt or a journey.

How to teach Tier 2 words

Morphology and etymology

Learning word families (words that share a common root) is an important part of broadening vocabulary. It can be useful to look out for such words when reading.

For example, when looking at the word assume, focus on the root ‘-sume’ which means ‘to take up’ (derived from the Latin ‘sumere’). To assume is to take meaning from something but this is just the start:

- Consume: to take and use up e.g. Being hungry, he consumed his lunch with vigor!

- Presume: to take onboard a thought or believe something without proof e.g. I presumed you weren’t coming and yet here you are!

- Subsume: to take something in or absorb something e.g. All of the information was subsumed under one heading.

Some of the other words in the passage from The Explorer also have interesting roots. Although exploring this will take some internet research, you will be expanding your own knowledge of words and how they work, as well as the children’s.

For example: compulsory has its root in the word compel which means ‘to drive together’ (from the Latin >com, meaning together, and pollere to drive). This provides a number of options for how you might dive deeper into this word, such as:

- How many words can you find with the prefix com that relate to togetherness? E.g. combine, community, comfort, and communicate.

- Can you add further affixes to the words above to create other words in the same word family? E.g. combination, telecommunication.

- Think about the meanings of the following words: connect, congregate, concord. Does the prefix con- have the same meaning as com-? How do you know?

Now, you are not going to study every word at this level of detail, but showing an interest and delving a bit deeper when the opportunity arises, will not only broaden children’s knowledge of words, but also their interest in how language works.

Simplifying definitions

I know that the words above actually have multiple, nuanced meanings that are not represented here. However, language is tricky. Sometimes simplifying definitions, as long as you don’t lose the meanings along the way, can help children understand how to use the word.

Based on my basic definitions you can see that each involves taking or taking in something – be it information, ideas or food. And you don’t need to be Susie Dent to plan such activities, there are many reputable websites that list root words and their meanings.

Become word nerds

Finally, be vigilant for those words that children just like the sound of. Learning language should be fun.

I often find myself talking about how, if you really want children to have a more expressive vocabulary, they must care about words and language; they must become ‘word nerds’!

We focus on word meanings and usage but sometimes it is just as important to ask the children what words interest them (regardless of their root or tier) and take it from there.

Thanks to Ruth Baker-Leask and Matt MacGuire. Ruth is a former primary head, director of Minerva Learning and chair of the National Association of Advisers in English (NAAE). Matt is an assistant headteacher. Visit his blog at Ten Rules for Teaching.

Using Rewordify to teach Tier 2 words

Streamline your teaching and reduce the anxiety around Tier 2 words with handy website Rewordify…

Probably the best thing about Rewordify is how easy it is to use. Simply copy and paste any piece of text into the box on the home screen, and press the ‘Rewordify text’ button.

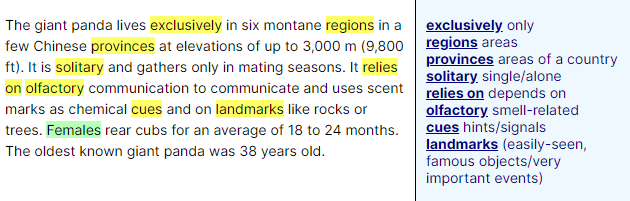

The website immediately identifies the Tier 2 words in the text and gives you a range of options. The default option is a copy of the text with all the difficult words changed into simpler ones, highlighted in yellow.

Pupils can read text fluently without being ‘interrupted’ by words they don’t know and having to check a glossary.

However, although this option is useful, I find that simply replacing the difficult language with simpler words does not help children tackle more difficult language; it certainly won’t help to embed new words into their long-term memory!

So, instead of sticking with the default option, I click the ‘print/learning activities’ button, which presents a menu of options.

From this menu you can immediately produce a copy of the text with all the Tier 2 vocabulary highlighted.

You can also create a glossary down the side with those words defined by choosing ‘Text with vocabulary’. This can be printed immediately with or without a space for the pupil’s name. They are now able to engage with more challenging vocabulary.

As I have already mentioned, even though a glossary will help a child to understand a piece of text, it will not help them retain that language.

There needs to be more interaction with the new words, including recall, before that language will be learned.

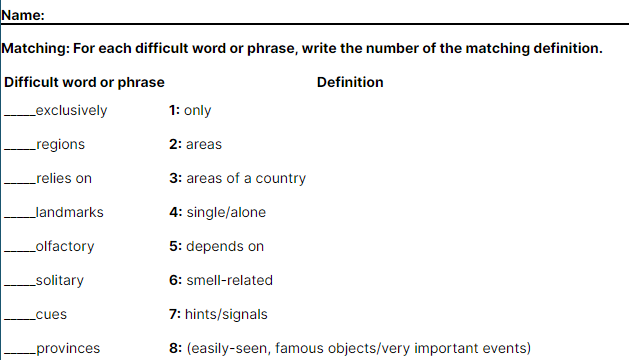

Thankfully, the learning activities menu contains a range of useful ideas for literacy activities; including matching exercises and quizzes with different levels of difficulty.

Example of using Rewordify in class

Firstly, I can take the piece of text I wish to use and run it through Rewordify. This will immediately identify and produce a list of the tier 2 vocabulary.

I can then decide whether to pre-teach it, or use the text with a glossary and further embed the vocabulary afterwards. If the vocabulary seems particularly difficult, I usually choose to pre-teach it.

However, if I feel that pupils will be confident and not overwhelmed, I use the extract with a glossary first and then embed the vocabulary in the following lessons.

For example, in our scheme of work we have an extract from Great Expectations: the extraordinary moment where Pip is confronted by Magwich in the graveyard. This is for a secondary class, but the approach would work just as well with an extract for KS2.

The description of Magwitch as a villain is vivid and terrifying. However, as a 19th century text there are several words that students wouldn’t understand.

I was able to identify all of the Tier 2 words in the text. Students then had a glossary to use while they were reading. After this, the matching exercises and word quizzes became literacy starters for the next few lessons.

Students would come into the room and immediately complete a matching exercise or a multiple-choice quiz in silence. You can scaffold this for KS2.

The regular use of multiple-choice quizzes in particular helped to embed the vocabulary from this moment in Dickens’ brilliant novel. Another benefit is that once I have created a glossary for an extract, I have it forever.

I can also add comprehension questions myself, thereby creating a powerful resource for my lessons.

I have done this for a range of gothic extracts; stories such as The Red Room and Dracula would not be accessible without sensible scaffolding. But, with the additions I have mentioned, students are able to explore the elements of a gothic story.

Dan Smith has been an English teacher for 12 years, and shares a variety of resources online. Follow Dan on X at @teach_smith and see more of his work at linktr.ee/TeachSmith. Browse more ambitious vocabulary resources.

Examples of teaching Tier 2 words in class

When reading Sonya Hartnett’s The Children of the King with his class, Mr Miller selected a small number of words to use as the basis of his vocabulary teaching each week. Here are two examples of his thought process:

Teaching the word ‘quailed’

Sentence: She heard it: footsteps in the dark. Cecily Lockwood, aged recently twelve quailed in the darkness beneath her bed and listened to the steps coming closer.

Vocabulary commentary: The word ‘quailed’ is unlikely to be familiar to most students. However, the general mood and tone can be understood from the context without knowing precisely what this word means. It is a Tier 2 word, but it has limited use and is more usual in older texts.

Teaching decision: Give a definition for ‘quailed’ during reading.

Teaching ‘drawn’, ‘ribbon’, ‘nosed’

Sentence: The curtains of her bedroom were drawn and only a ribbon of light nosed past the door.

Vocabulary commentary: ‘Drawn’ has more than one meaning. It’s likely that students will know ‘to sketch’ and the verb ‘to draw the curtains’.

It can also mean ‘pale and haggard’, ‘to pull something out of a pocket’ (eg to draw a pistol) or ‘to shrink’. It’s a good Tier 2 word.

‘Ribbon’ may be familiar as a strip of material, but is less likely to be known in a more generalised context, eg a long, narrow strip – as in vegetables cut into ribbons, or metaphorically as a ribbon of light. Ribbon is also a good Tier 2 word.

While students will know the noun ‘nose’, the use of ‘nosed’ in this context is more likely to be found in literary texts and may be confusing to some readers.

Teaching decision: There is no need to take any action with the word ‘ribbon’ (teaching more than five words in depth is counterproductive, so you have to weigh up the relative merits of teaching each word). ‘Drawn’ or ‘nosed’ could be selected as words to teach after reading.

Using semantic mapping

Reading the poem ‘Maggie Dooley’, about an old woman who feeds stray cats in the park each day, with her Year 4 class, Mrs Wright wasn’t expecting the words to cause much difficulty.

But it quickly becomes apparent that the word ‘family’ is proving to be a barrier to understanding. The children can’t get past the idea that it must refer to Maggie’s own children.

She sits by the children’s

Roundabout

And takes a sip

From a bottle of stout.

She smiles a smile

And nods her head

Until her little

Family’s fed.

Mrs Wright guides the group to think about how pets might be considered ‘part of the family’, but the class can’t seem to get past a literal interpretation of the word – ‘family’ means ‘relatives’.

What is semantic mapping?

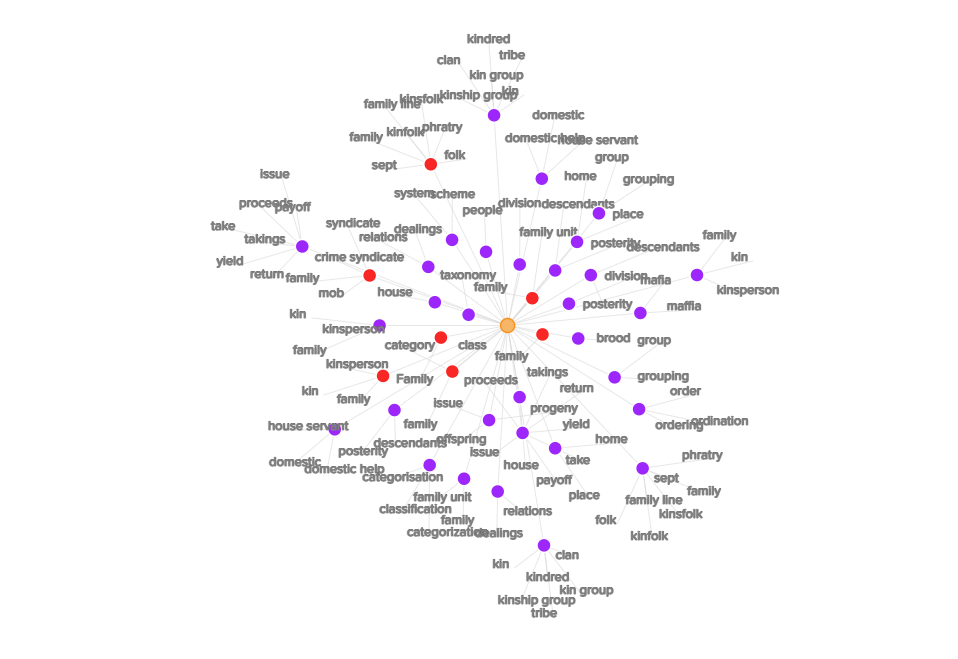

Semantic mapping is a graphic strategy that establishes the schematic relationship between words and enables students to develop a deeper understanding of concepts.

Children can activate and organise their prior knowledge, and are guided to structure that knowledge into formal relationships. All concepts have at least three different types of association:

- Association of class: The order of things. So within the class ‘family’, we might include mother, father, brother, sister etc.

- Association of property: These are the attributes that define the concept – so for ‘family’ these might include home, security, belonging.

- Associations of example: The Royal family, my family, a pride of lions.

How to create semantic maps

Semantic maps are created together by the teacher and students through dialogue, making the different types of association between groups of words explicit.

Used to develop a deep understanding of Tier 2 words, they are working documents, with pupils adding new ideas as they progress through a sequence of work.

Going back to Mrs Wright’s class, the key question is, ‘How has your understanding of the word ‘family’ changed since reading the poem?’.

The step-by-step process

- Before reading ‘Maggie Dooley’, Mrs Wright writes ‘family’ on the IWB and asks pupils to suggest words they associate with it, before adding them to the board.

- She makes a couple of suggestions designed to encourage the students to think more broadly. After one child says ‘love’, she adds ‘jealousy’, which sparks suggestions of negative emotional words.

- Mrs Wright reviews the list with pupils and asks them to suggest links between words. These word groups include relatives (mum, dad, granny, grandma, uncle) and feeling safe (protected, safe, secure, happy, take care, look after).

- Mrs Wright models how to group these words using a semantic map, explaining that words can fit in more than one group. In threes or fours, students complete their semantic maps and feed back to the class.

- In pairs, pupils review their semantic maps and decide which aspects of the word ‘family’ Charles Causley was implying in ‘Maggie Dooley’. They highlight key words and phrases (evidence) in the poem.

More ideas for working with Tier 2 words

- After creating your semantic map, generate one by typing ‘family’ into lexipedia.com. Ask pupils to review their own maps and annotate them.

- Use Pinterest boards or visual word walls to build up word meanings.

- Try forced association – juxtapose two seemingly unconnected target words and ask the pupils a question, eg for ‘family’ and ‘stray’, ask ‘Can you have a stray family?’ or ‘Can a family stray?’.

Nikki Gamble is Associate Consultant at UCL and Director of Just Imagine.