Safeguarding in schools – What should your priorities be?

How can you protect both children and staff while going beyond checklists and risk assessments? Join us as we explore this vital issue…

- by Hannah Carter

- Experienced headteacher and author Visit website

Hannah Carter examines what leaders’ priorities should be when it comes to safeguarding – from health and safety in school, to visits home…

After 15 years in school leadership, there’s one truth I can’t escape. It sits with me, long after the building is empty and the emails have stopped for the day, and it’s this – schools are risk factories.

From health and safety assessments inside school to the decisions made during home visits, school leaders are expected to manage an environment in which nothing must go wrong. Ever.

Our professional duty, as set out in law and policy, demands no less than the absolute safety of every child. So we build systems. We write policies. We complete risk assessments and promptly review them again.

And even then, every single day, safeguarding remains not a matter of certainty, but probability. To be clear, we’re not ‘eliminating risk’. What we’re actually doing is managing the unmanageable, because risk isn’t some fixed enemy we can defeat once and for all.

‘Risk’ is the endlessly shifting ground we stand upon, with leadership being a matter of deciding which risks must be addressed immediately, and which can be briefly tolerated while we decide how to act.

Static risks versus real risks

Leaders are trained in identifying hazards. Wet floors, fire exits, unlocked gates, faulty fencing – these are all familiar, plainly visible and reassuringly solvable hazards.

Health and safety assessments will often tend to focus heavily on static risks, yet the most serious safeguarding ones will rarely be contained neatly inside a form.

The real danger lies in dynamic risk – those things that change hour by hour. The pupil who appeared settled in Period 2, but is now sending out worrying messages by lunchtime. The parent who ends a phone call calmly and then waits outside in the car park. The staffing gap that coincides with a distressed child.

I remember arriving at work one Monday morning before 9am and finding three ‘urgent issues’ on my desk. One was a safeguarding concern that involved a child’s unexplained bruising. The second was a report of total boiler failure (during winter). And then there was the governor demanding that I immediately return their call about the wearing of school uniforms.

Which was the biggest safeguarding risk? The bruising, obviously. But – if the school’s heating did, in fact, suddenly switch off and then stay off, hundreds of pupils would need to be sent home, with their supervision shifting to environments we know may be less safe than those in school.

This is the reality of leadership. Health and safety assessments capture hazards, but safeguarding requires leaders to constantly reassess risk in context.

What matters most isn’t whether you completed the form or not, but that you noticed when the risk changed.

Tick-box training and its limits

Safeguarding training rightly focuses on identification. Spot the signs. Record the concern. Report it. That all matters, but it’s just the start.

Identifying a concern is perhaps 10% of the challenge. The remaining 90% revolves around what happens next. Do you contact social care immediately or speak to the parent first to gather more information – while knowing that simply by doing so, you risk alerting them?

The police say they can’t attend within the next two hours. The child is distressed. What’s your risk tolerance during that window?

Training rarely prepares leaders directly for such moments. Instead, it provides attendees with flowcharts and templates. But these will usually be designed with orderly situations in mind – not the ever-messy realities of human behaviour.

As a DSL, my main frustration was the false comfort provided by paperwork. We would spend hours assessing the risk of slips, or property getting lost on a routine trip, only for the real safeguarding issue to involve a sudden mental health crisis triggered by something entirely unpredictable.

Templates make us feel compliant; they don’t make us safe. Yes, health and safety assessments remain essential, but safeguarding is a mindset.

Leaders need training that actually develops their judgement, rather than simply ensuring their compliance.

Present people with potential scenarios where every option carries some level of risk and make them explain their reasoning. That is how safeguarding confidence is built.

In-school priorities

So, what should leaders focus on first? I’d start with the ‘5-minute rule’, which holds that when a pupil or colleague brings you a concern, stop and give them at least 5 minutes of your undivided attention.

That means no laptop, no surreptitious scanning of emails. Information is the most powerful safeguarding tool we have, but the moment someone feels dismissed, it disappears.

I once brushed off a child’s vague comment about ‘A man with a funny hat’ near the fence. Days later, that description matched someone police were searching for. I’d heard the words, but hadn’t listened properly.

Next, there’s the ‘What if?’ Audit, where you take your health and safety procedures and then stress-test them with your most practical colleagues by considering the following:

- What happens if the DSL and First Aider are both off-site?

- What should you do if the fire alarm sounds during a lockdown?

- How should you respond if a parent arrives at pick-up intoxicated?

Don’t just write the answers down. Walk through them, practise them, because that’s how risk assessments stop being theoretical and actually start becoming meaningful.

Safeguarding the adults

Student safeguarding can’t be separated from staff safety. The risk to adults in school will often be underestimated, but it is real.

One such risk can be malicious allegations. A false accusation will still automatically trigger formal processes – and rightly so – but for the staff member involved, everything stops.

And even when cleared, the impact can linger. Leaders must therefore provide clear policies, transparent processes and unwavering internal support where staff have acted appropriately.

Another risk faced by staff is that of violence. Trauma doesn’t always present quietly – indeed, I’ve seen experienced, caring staff injured in a matter of seconds.

Mitigation here will entail genuine de-escalation training, realistic staffing decisions and a culture in which taking a step back is seen as a mark of professionalism, not weakness.

Protecting staff shouldn’t be seen as separate from safeguarding students, but very much part of it.

Home visits

Home visits remain one of the most uncontrolled safeguarding risks that leaders accept. The rules here should be non-negotiable:

- Go in pairs.

- Log where you are and when you expect to return.

- Agree on a clear exit code ahead of time that signals the need to leave immediately.

You can’t control what happens inside a home, but you can control how you enter and how you leave. Courage isn’t a safeguarding strategy.

Holding the balance

The safeguarding office isn’t an administrative space, but rather a risk management hub. Every decision made there will be a response to some threat, whether known or emerging.

We want certainty and we want guarantees, but safeguarding is about managing impossible trade-offs with imperfect information.

If, at the end of the day, children and staff are safer than they were that morning, then the equation is holding. Forms don’t keep people safe. People do.

Hannah Carter is an experienced headteacher working for The Kemnal Academies Trust, and author of the book, The Honest Headteacher (Teacher Writers, £12.99). Browse resources for Child Safety Week.

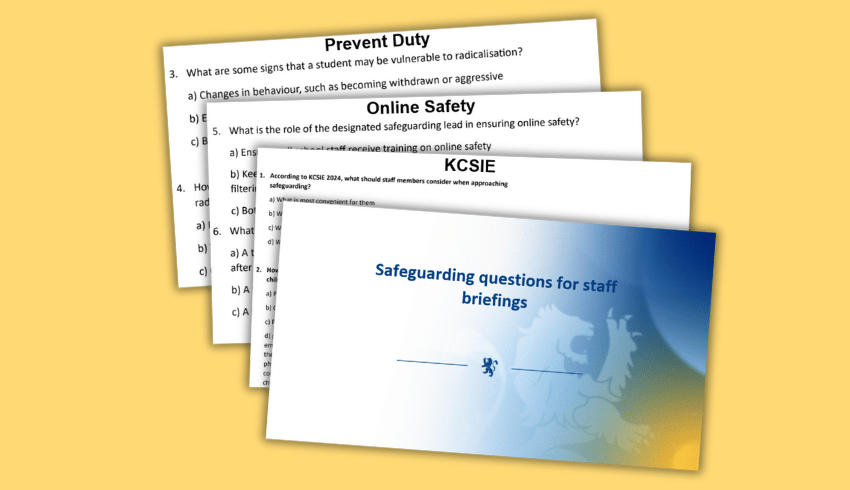

Safeguarding quiz

This free safeguarding quiz PowerPoint contains 128 slides of multiple-choice questions, ideal for staff briefings. Each set of 10-12 questions covers a mix of topics.

Using technology to strengthen your school safeguarding

Safeguarding and technology are deeply interconnected. By keeping strategies straightforward and focused, you can help to ensure that technology enhances your school’s safeguarding mission…

Set clear policies and procedures

It takes everyone in a school to keep children safe, which is why clear safeguarding policies and procedures matter.

Schools should avoid vague or confusing language in shaping safeguarding guidelines. A simple statement of a school’s commitment to protect all children online can underpin everything else – including clear instructions on how teachers should report safeguarding concerns, gather key details and contact parents.

This will help to ensure you manage issues confidently and consistently right across the school.

Establish robust systems for safeguarding support

Technology can be a powerful safeguarding tool in schools, but the systems teachers use must be set up to prevent children who may be at risk from slipping through the cracks.

Software that flags unexplained absences in real time will help teachers identify any safeguarding concerns and respond to them quickly – but if a system automatically generates alerts throughout the day when a child is off school ill, it can distract the teacher from spotting genuine issues requiring immediate attention.

Engage partners

When you have a child who is being bullied online it’s not always easy to know how to help. But teachers aren’t on their own when it comes to keeping children safe.

The relationships between schools and parents can be a firm foundation from which to start addressing issues together.

With support from both home and school, it’s easier to spot signs of social withdrawal, anxiety or declining academic performance that may indicate a child is struggling.

Schools concerned about cyberbullying can also partner with local charities specialising in teaching young people about online safety and mental health. School staff can then keep their focus on the safe use of tech for learning.

Regular training

Not every teacher has the technical knowledge and skills to keep sensitive data on young people safe. Regular training can help staff use the tools they have access to more effectively, in line with broader safeguarding policies.

Teachers need to know how to use their own mobile devices to access and share student data securely, for example.

A regular course aimed at keeping their skills up-to-date could help them work more efficiently, without putting sensitive data at risk.

The right CPD will give teachers more confidence to explore the exciting digital tools available to enhance their teaching.

Matt Tiplin is a former school senior leader and Ofsted inspector, and currently VP of ONVU Learning.