Pupils With ADHD Becoming Disengaged? Here’s How To Keep Them Interested

If you’ve ever checked Facebook in a staff meeting, you’ll know why it’s so important to tap into what each child, especially those with ADHD, finds truly interesting, says Letitia Sweitzer…

We are not free. We are continuously contained, directed, limited, required, forbidden, prevented, and restrained. We are thereby productive, appropriate, out of trouble, safe from harm, polite, employed and sometimes paid. We are sometimes bored. If we have ADHD, we are often bored, restless, dissatisfied, frustrated, and very often not our true selves. Dealing with boredom is much easier when we are free to do whatever we want.

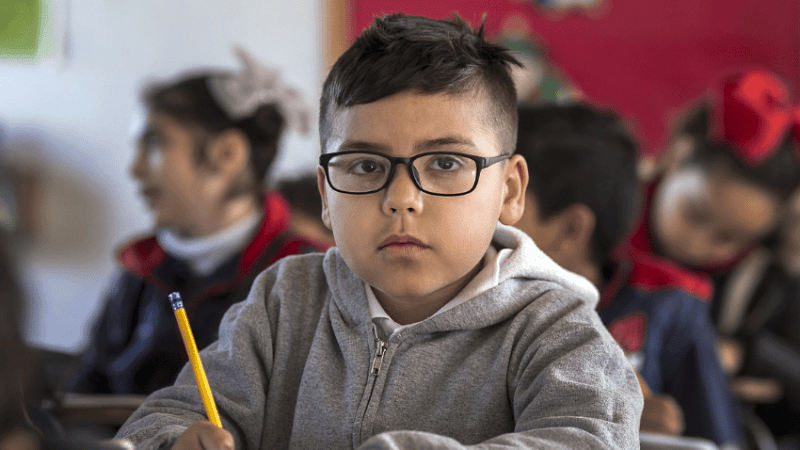

Seven-year-old Ryan is bored while waiting with his grandfather to be seated at a table in a restaurant. He sits briefly in a stuffed chair beside the door. Soon he kneels on the seat of the chair and looks up at a picture on the wall behind it. It’s a landscape, the same boring landscape that is outside the restaurant. He butts his head against the back of the chair.

“Turn around, Ryan,” says his grandfather. Ryan turns around and swings his legs. Then he spins around again and inches his legs up on the chair back, letting his head drop off the seat. His grandfather admonishes Ryan: “Sit up properly.” ‘Properly’, for Ryan, is the byword of boredom.

Compare that scene with one at home in which Ryan has been interrupted while building a bridge for dinosaurs out of Lego. His mother has asked about his homework. He says he hasn’t done it and he doesn’t remember what it is. His mother looks in his backpack and finds an assignment to write six sentences about his pets.

“I can’t think of anything to say,” he says.

“It’s hard to think of things when that’s not what you’re thinking about right now,” says his mother. “And I bet it’s even harder to think of six things to say about your pets if you’re upside down on the sofa.”

Ryan gets a twinkle in his eye. It’s the first time his mother has said anything like this. He immediately drops the Lego, flops on the sofa, and lets his head drop off the front, all the way down to the floor. He says nothing, just enjoying the new position. His mother repeats, “See, you can’t think of even one thing to say about your pets when you are upside down.”

“I can too,” he says, “Darth is black and Vader is black with white on his chest. That’s how I can tell them apart. They aren’t exactly afraid of Winston (the dog), but they sneak around the side of the room when he’s lying off the sofa, pulls the paper out from under it, and puts it in his backpack, from where with luck – and a grin – it will be pulled out and handed in at school the following morning.

Ryan and his mother both know what has just happened here – though his mum understands just a little bit more. She has given Ryan a half dozen of his Elements of Interest (see ‘What floats your boat?’, right): novelty, physical action, humor, curiosity, challenge, and surprise.

The difference between that scene and the one in the restaurant was basically the freedom to be upside down in a chair. How often is a child really free? And how much less freedom is there for a child in a restaurant? What could the grandfather have done with Ryan in this situation? What freedom could he have given his fidgety grandson?

As an alternative to a reprimand, he could have asked Ryan to walk quietly down the hall like a giraffe and come back like a squirrel. He could have given him a task to do: “Go over to the bulletin board and see what’s on it and come back and tell me about it.” He could have planted a penny or two in a magazine on the table and said, “See if you can find a penny in this magazine, I have a feeling someone might have left one or two inside it.” But first a grandfather has to understand that waiting in a chair for dinner is boring for anyone, that Ryan, being a child with ADHD, is especially boredom prone, and that he needs a few tricks, not a scolding.

Many of us are bored if we have to be still for too long. Freedom to seek interest is what we all need – and a few tricks. Ryan has ADHD, but it doesn’t really matter if he does or not. What’s good for ADHD is good for everybody who is stuck in a boring situation.

What floats your boat?

Think about everything you like to do, and you’ll often discover common themes…

It’s important not to assume you know what is interesting to a child – it’s better for your pupils to discover and embrace their own interests. Also, while it is obviously good to know their preferences such as subjects, sports, or hobbies, it’s more important to recognise the portable, lifelong ‘Elements of Interest’ that favourite activities involve. I use the term to mean the underlying aspects of an activity that excite them versus a complex interest such as history, lacrosse, or model airplane building, which involve many elements of activity.

The person who loves to play football may love it because physical action and competition are among his Elements of Interest, but it may be that the social aspects of affiliation and social interaction with the team are more important Elements of the game for him. Your job is to help him focus more on the Elements than the activity.

Letitia Sweitzer M.Ed, BCC, ACC is trained in ADHD coaching by the Edge Foundation (edgefoundation.org). Browse more resources for ADHD Awareness Month.