Primary history curriculum – how to build learning year-on-year

Connect past, present and future, and help pupils build on history learning throughout primary school

Over the past couple of years, primary history teachers have spent countless hours rewriting, resequencing, and refocusing their curriculum so that it is in line with the current Ofsted inspection focus.

There are many schools with clearly defined curriculum sequencing in place and a growing understanding of the building blocks of knowledge, so thinking about how we can link learning within and across year groups is a useful next step.

If you’ve heard me talk on this before, you will know I like to present the history curriculum as an open-ended framework which is full of possibilities.

This is also how it was described in 2013 by the Historical Association’s Alf Wilkinson alongside the greater emphasis on the ‘big picture of history… of making sense of how it all fits together.’

A core aim of the National Curriculum for history is to support children’s ability to ‘gain a coherent knowledge and understanding of Britain’s past and that of the wider world. It should inspire pupils’ curiosity to know more about the past.’

Tim Lomas wrote about coherence in issue 76 of the journal Primary History’s, too, and said, ‘Coherence is often best achieved when pupils see the links, connections and inter-relationships across periods, themes and events.’

As such, I wanted to share some approaches that can support children’s ability to make those critical connections between what they have already learned, and what they’re about to encounter in a new academic year.

History timeline KS1

Chronology has a two-fold purpose in that it helps us organise the past, alongside being an important historical concept in its own right.

I have written about timelines before, focusing on how they can be constructed to depict more than just an arbitrary sequence.

When focusing on connections, constructing timelines is less critical than what we do with them.

When we deconstruct what the timelines depict, the role of the teacher is similar to a narrator in a story, helping children to understand the characters, settings, and events, and make more sense of the abstract historical world.

The National Curriculum explicitly talks about connections for KS1 and KS2 history in the processes paragraphs and Aim 6.

Specifically, around being able to ‘identify similarities and differences between ways of life in different periods’ in KS1.

This can be accomplished by using timelines to organise children’s understanding of when in the past they are learning about, and how it sits alongside what they have learned previously.

Once the children can identify this, the teacher can support them to understand a number of core ideas: why life was different; what technology would have impacted life (think no fire engines in the Great Fire of London); and why making comparisons is helpful when learning history.

History timeline KS2

KS2 directly builds on this by ‘establishing clear narratives within and across the periods [of] study.’

The purpose of this is to ensure that children don’t see the past as isolated chunks of time that are unrelated to each other.

This is for two important reasons: first, it’s factually inaccurate, and second, it deprives children of the ability to see history as a narrative-driven subject.

When pupils are familiar with the sequential order, let’s use that to our advantage by revisiting the timeline with a specific concept in mind.

For example, if we focus on the economy, ask ‘How did most people earn a living?’. What emerges is a huge turning point in the neolithic era with the transition to agriculture, and then another in the late 18th century with industrial revolution.

It’s key that the purpose of the timeline isn’t lost – the children need to interact, debate, discuss and consider what it says.

One important addition alongside this is maps! Not only should we consider when in the past we are learning about but also where in the world. Both are key to developing understanding, and combine to provide greater clarity over future learning.

Knowledge building

The current inspection framework defines ‘progress’ as ‘knowing more (including knowing how to do more) and remembering more’, and stipulates that ‘when new knowledge and existing knowledge connect in pupils’ minds, this gives rise to understanding.’

Progress was also referenced several times in Tim Jenner’s Historical Association conference talk 2022 as ‘building knowledge of concepts through repeated encounters’.

This is an approach I actively use in the classroom as it allows me to ensure children have retained what they were taught previously and therefore I have a more solid foundation upon which I can add depth in the new topic.

To facilitate this, we need to define the core knowledge for the history curriculum to ensure subsequent teachers know what they are building on.

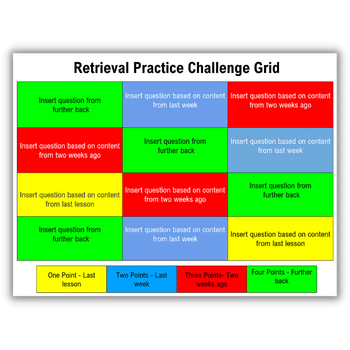

When teaching, I often start with a low-stakes quiz. This is nothing uncommon in classrooms but, after reading a piece in TES by Mark Enser, I adjusted the nature and use of the questions.

Firstly, I ensured to emphasise retrieval of definitions around concepts that were key in the lesson ahead. This has helped the children make connections because they are actively built into the teaching sequence.

Secondly, I used some of the questions to generate learning by selecting information and then doing something active with it.

In UKS2, for example, we focus an enquiry on whether King Alfred deserves to be known as ‘the Great’.

This draws attention to his actions in relation to Viking conquest, defending his kingdom, reforming aspects of state and subsequent interpretations of his reign. This is especially useful when a concept such as monarchy is fundamental to an enquiry.

As part of this, it is helpful to have a clear definition of what you’re actively investigating.

In this case, what a monarch is and their role in societies; previous examples including key decisions they made (think Charles II in the Great Fire of London) and the ability to link them together. Some of the questions we use are:

- What is a government?

- Can you match the definitions to the correct type of government (democracy and monarchy)?

- Who is the odd one out and why? (Boudicca, Emperor Claudius and a Pharaoh).

By consistently making these kinds of connections, children are used to it being a core part of the lesson, so they engage independently and see it as a way to help them understand the subject.

The initial fears some pupils had about getting questions wrong were reduced when they realised the retrieval process was there to prompt remembering and not as a test where scores were calculated and shared.

There is much more support available in Kate Jones’ new book, Retrieval practice: Primary: a guide for primary teachers and leaders – I heartily recommend purchasing it.

Stuart Tiffany is a primary teacher, history CPD provider and consultant. He supports schools to embed the historical discipline within their curriculum. Follow Stuart on Twitter @Mr_S_Tiffany and see more of his work at mrtdoeshistory.com