Post-COVID catch-up – Why slowing down is key to recovering students’ progress

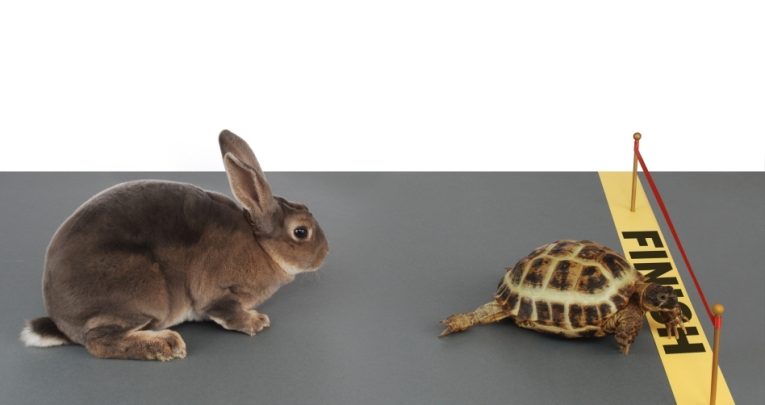

To make up for COVID-related lost learning, educators should try to cover what’s been missed ASAP, right? Not so fast, advises David Lowbridge-Ellis…

It would be easy to think, with all this talk of ‘catch-up’, that the best approach for mitigating the learning loss of repeated lockdowns would be to go as fast as we can through the curriculum. But nothing could be further from the truth.

To echo the immortal words of Taylor Swift, we need to calm down. And that means slowing down. Slowing down might seem counter-intuitive when we’re all trying to get our pupils caught up as quickly as possible, but we can’t pass on our own anxieties about curriculum coverage to our pupils.

The coverage trap

The last year or so has been strange for all of us, but perhaps the most bizarre thing I’ve heard about is a school that told all of its subject leads to carve up the curriculum into equally- sized chunks, so that they could be sure to ‘cover’ the curriculum in time.

This would mean that in science, for example, the teachers would make sure that they ‘covered’ four pages of the textbook every lesson, regardless of whether the pupils had actually learned the contents of those four pages.

As Harvard educationalist and developmental psychologist Howard Gardner famously stated, “The greatest enemy of understanding is coverage. As long as you are determined to cover everything, you actually ensure that most kids are not going to understand.” I’ve found myself quoting Gardner regularly this year – usually whenever someone introduces the word ‘coverage’ into a discussion about the curriculum.

It’s easy to see why going hell for leather through units and topics is commonly seen as the best, if not only course of action. Given the pressures of external accountability, we need to make sure our children are making enough progress to do well in their exams. Even with performance tables being suspended for a couple of years, this is hardwired into us.

The result is often a form of short termism that sees a disproportionate amount of resources (principally our strongest teachers) intensively channelled into Y11. But throwing as much at pupils as we can and hoping it sticks is the wrong way to go about things.

Instead, we need to take some deep breaths and engage with the complexity involved in having to constantly re-plan our curriculum. Because COVID and its aftermath is something we’ll all be dealing with for years to come.

Five questions

There are five questions that I’ve been repeatedly asking curriculum leads this year, and will probably be continuing to ask for the foreseeable future:

1 | Are you checking thoroughly for gaps in knowledge and understanding?

2020-21 was the year of Checking For Understanding. I started using the capital letters in all of my communications to show its importance.

At this point, as a profession, we should be well beyond a mere list of ‘AfL strategies’. Teaching is feedback and feedback is teaching. Even so, this year teachers really had to up their game in making Checking a routine part of everything they did.

The principle of Checking before you deliver anything was essential for identifying where there might be weaknesses in pupils’ knowledge foundations. With dodgy foundations, everything else might collapse – though fortunately, the metaphor only goes so far.

Pupils aren’t collapsing buildings; we can fix rickety foundations, shoring them up until they can stand unsupported once again. But before we do anything else, we need to Check.

2 | How are you adapting the planned curriculum based on this Checking?

All of the subject leads I worked with this year realised very quickly that their beautifully planned schemes and units would have to be substantially adjusted after they found that what pupils had learned over lockdown was… variable.

There is safety in a pre-planned scheme, but following it slavishly is fatal. The word ‘roadmap’ has taken on new connotations. Inside classrooms, our maps have to be flexible. Having a destination in mind and sharing it with pupils remains essential, but even more so than before, we have to be ready to find alternative routes of getting there.

3 | Are there any bits of the curriculum you can ditch entirely?

I feel very uncomfortable taking a utilitarian approach to the curriculum, teaching pupils only the things they ‘need’ to know. Even so, we do need to make some difficult decisions. In languages, for instance, do they really need to learn all of that vocabulary?

I’ve worked with a fabulous MFL lead this year who has split the curriculum into ‘need to know’ and ‘nice to have’. In the former, they had the verbs that pupils could use when talking about multiple topics (home, school, holidays, etc), while more context-specific items were grouped together in the latter.

4 | Where must you slow down to re-teach elements? Are there areas where you can speed up?

Some subject leads, particularly in the sciences and humanities, may baulk at missing out anything which appears on the specification. I get that – there’s a chance it could appear on the exam.

But if we’re spending more time rebuilding foundations, then we need to find the time from somewhere. And not all knowledge is created equally.

The subject research summaries being released by Ofsted over the next two years are helpfully drawing more attention to the importance of identifying substantive concepts – those things which unlock bigger chunks of learning. Ofsted held curriculum roadshows explaining these at the end of the summer term, with accompanying videos now available to view on YouTube.

5 | When weaknesses in pupils’ foundational knowledge are discovered, how will you address them?

This is definitely a case of ‘when’, rather than ‘if’. We’ll be finding these weaknesses for a long time yet. My mantra with all the teachers I’ve worked with over this past year has been assume pupils know less than you think they do.

This isn’t a case of us having low expectations of pupils. We can always speed up if we’re confident they’ve thoroughly understood and comprehensively remembered what they’ve been taught – but almost every time, that’s simply not the case.

Assumptions are dangerous things, and it’s always better to Check the extent of learning loss and proceed accordingly. But amid the hectic day-to-day goings-on of a school, we can sometimes lose sight of this and seek shortcuts.

The best thing we can do to alleviate our stress – and that of our pupils – is adopt ‘they know less than I think they’re going to’ as our starting position, and then not be disheartened when we have to take things more slowly than we’d originally planned to.

David Lowbridge-Ellis leads on school improvement across Matrix Academy Trust in the West Midlands; follow him at @davidtlowbridge.